A Vogue Idea is a column by Matthew Linde exploring contemporary fashion practice.

___fabrics interseason was founded by Wally Salner and Johannes Schweiger. Since 1998, they have produced twenty-two collections, initiated a bachelor’s degree program in fashion design for Kunstuniversität Linz, and have participated in more than twenty exhibitions, including the third Berlin Biennale and Manifesta 7. The term “interseasonal,” which refers to clothing that falls outside the two major annual shows, is suggestive of design’s liminal space.

Their work, along with labels like BLESS, has been canonical for opening new interdisciplinary models for fashion. While haute couture challenges wearability through the spectacular, ___fabrics interseason instead explores clothing codes through a sociopolitical approach to fashion rituals. Although the label ended in 2011, their nuanced criticality still echoes today, in contrast to the hyper exposure of the fashion industry.

___fabrics interseason was a curious example of a label that existed on the periphery. Your work dealt with installations, performances, music and material studies. What was your interest in anchoring this practice in fashion?

Johannes Schweiger: We had no background in fashion studies, but we both, Wally Salner and I, studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. During my studies, my artistic projects already dealt with issues of clothing and fashion. It was not really about making garments or wearable props, but more about an institutional critique of the system of fashion — modes of presenting, mediating and consuming fashion.

In the beginning, ___fabrics interseason had a strong focus on the performative aspects of fashion, literally using the method and form of a fashion show as a tool to communicate social issues and phenomena. Even then the garments of our collections were not necessarily designed under a fashionable/wearable aspect. I would say this started when we founded the company and went to Paris to present our collections during fashion week and further sold them to shops worldwide. ___fabrics interseason had a broader brand philosophy, and its approach toward fashion combined design, fine arts, music, film and text in a simple and natural way.

Working from and at the periphery allows you to stay in focus. It might also mean that your gaze at the center is critical and objective, if the center represents a corporate-run brand whose only aim is to have a huge turnover by the end of the year.

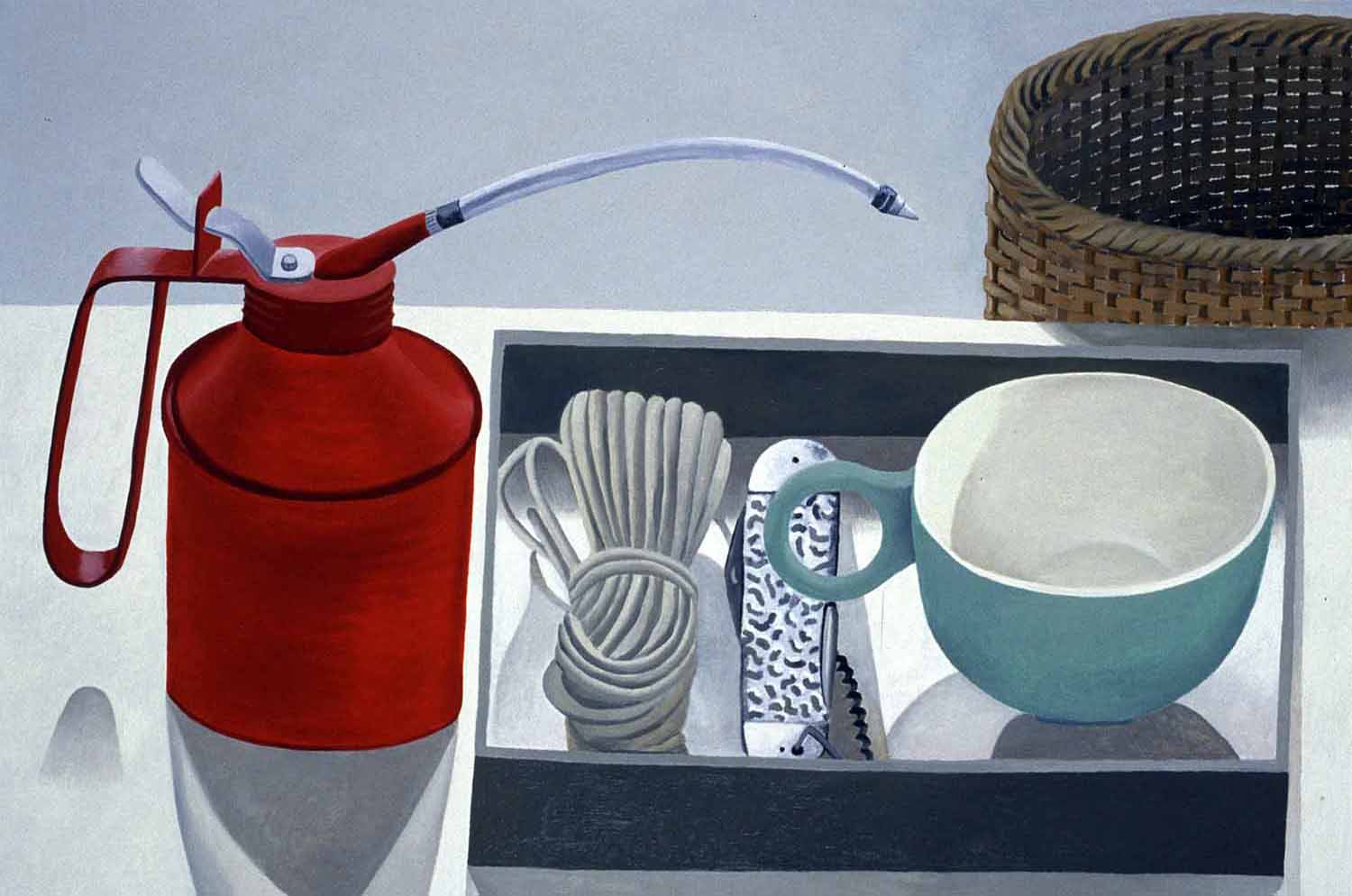

The collection descriptions are often long, impressionistic explanations of cultural phenomena, functioning as ficto-critical analyses to frame the collection. Topics have ranged from Tupperware, Japanese consumerism, masculine anxiety, etc. What was one of your favorite collections/works?

That’s difficult to answer after such a long time, but it might be a trilogy of collections dealing with the subject of normality projected on the surface in different fields (Spring Summer 2002, Fall Winter 2002/03, Spring Summer 2003). The series was called “constructed normality” and had the subtitles #PromesseDuBonheur, with the focus on “New Poverty;” #ModernNervs, dealing with psychic (ab)normality; and #clubMed CHLOR, in which we concentrated on the idea of gated holiday resorts and female sex tourism in the 1980s.

Your collections often addressed a loose fabric that, as an abandonment of the anatomy, is also explored in your installation work. This provocation of fashion’s boundaries was also being tested by another label, ffiXXed, who approached fabric’s multiplicity in translating non-garment outcomes. What is your relationship to fabric in your installation work — for example the piece for Manifesta 7?

For Manifesta we continued with a project we realized a year before (tapestry #1). In this open-air installation we worked with handwoven rugs and carpets that were made of the leftovers from all the previous collections, cut into thin strips and woven in the most simple way you can imagine: warp and weft. The idea behind it was not really a recycling aspect but more the leveling of different collections (with all their concepts) into a new design product. The carpets/textiles can also been seen as a form of painting and have different dimensions, the biggest ones measuring two by twenty meters.

One of my favorite collections was “Adhocracy f/w 2004/05,” which was also featured in the third Berlin Biennale. Could you explain this work?

“Adhocracy” was conceived both as a collection and an installation piece that included a performance for the third Berlin Biennale. Then, almost fifteen years ago, the rise of smart technologies and the phenomenon of the flash mob was quite virulent, and we linked this idea of Dadaistic nonsense gatherings with the Surrealists, who handed out heads of lettuce to passersby to bring some fantasy to the course of standardized, everyday life. But do not forget: the surrealists were an elitist group. Anybody who acted against the imaginary disordered rules was quickly conjured away!

The principle upon which these ad hoc groupings came together was simple: sometime, somehow, somewhere. We questioned if this phenomenon could be the future of democracy, a kind of a high-speed variant of democratic consent-formation in the age of wireless communication. For its presentation during Paris fashion week, we organized a fake flash mob at the Louvre/Union Central des Arts Decoratifs, where the group of models lip-synched Kevin Blechdom’s interpretation of Tina Turner’s “Private Dancer.”

What was it like heading a fashion course at the university in Linz? What was your approach to fashion pedagogy?

Working with students is a matter of giving and taking. Of course there are specific curricula to which you have to stick to, but the most important thing with teaching is to stimulate and promote independent thinking: free thinking is for free! I am still doing design seminars in Linz and at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, but I mainly teach at the Technical University of Dortmund, at the Institute of Art and Material Culture/Anthropology of Textiles. Wally Salner is teaching in Munich.

Are you still interested in fashion today?

Of course, I follow fashion. I still think it’s an interesting and powerful tool to communicate with your surroundings and mediate certain issues via fabrics and garments.