I’d seen the artist list, read the press release and scribbled a couple questions on the outbound flight. It was a given that the 32nd Bienal de São Paulo would reflect the recent turmoil in Brazil. But I was completely unprepared for Hotel Unique.

A nautical-themed design curio, Unique was housing a bunch of us in town for the biennial. The building sits to the back of an empty private plaza on the congested Avenida Brigadeiro Luís Antônio. It presents the approaching guest a vast semicircular façade — round on the bottom, flat on top — tiled viridian and covered in portholes. Apparently moored upon a low-lying structure of bent steel and glass, the ship is further secured by a wall that connects at the tip of the stern and another at the bow, and which together give the impression of a kind of scaffolding. This isn’t just some boat. Hotel Unique is the ark, awaiting cleansing rains, the rising waters that will carry away the design aficionados within.

A shroud of gray clouds covered São Paulo, and through my porthole window I watched clusters of people mill about the sidewalk across the plaza. Facing the ark expectantly, even menacingly it seemed, they were held off, for now, only by the armed guards. I’ve seen a lot of zombie movies.

And glimpsed from afar, the succession of scandals and crises unfolding in Brazil in recent months played like scenes out of a tropical apocalypse: a public health emergency; the forced removal of poor urban communities; a costly and mismanaged Olympic extravaganza; and, most importantly, the parliamentary pageantry of the soft coup. And all of this, of course, has unfolded against the backdrop of an economy, once celebrated as a neoliberal success story, in contraction since 2014.

If the biennial is something of a subdued affair, it is so only by comparison to this spectacle of calamity and political reaction. It’s not for want of trying. The curators, in fact, made catastrophe an organizing principle. “In order to objectively confront the big questions of our time,” the exhibition statement reads, “such as global warming and its impact on our habitats, the extinction of species and the loss of biological and cultural diversity, economic and political instability, injustice in the distribution of the Earth’s natural resources and global migration, among others, perhaps it’s necessary to detach uncertainty from fear.”

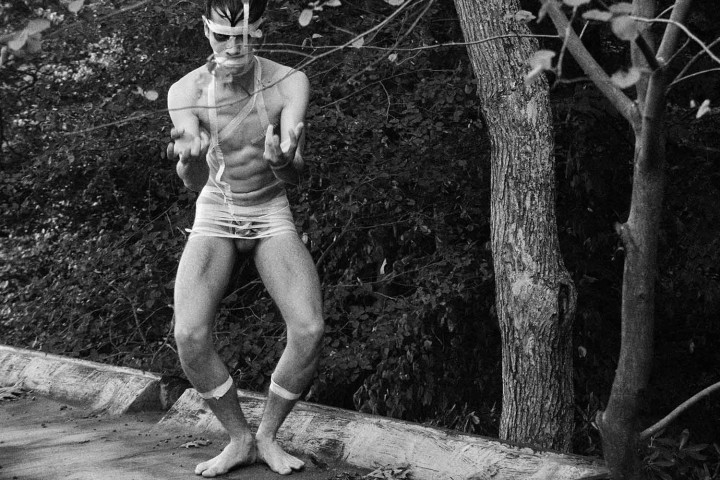

Perhaps. But the way this suggested detaching seems most commonly to work is through a set of archaizing styles, practices and themes: handicrafts, myth, indigenism and dirt. There is a profusion of natural materials. Frans Krajcberg’s sculptures open the show with a totemic grove of burnt Amazonian trees, whittled and painted (Gordinhos, Bailarinas and Coqueiros). Dineo Seshee Bopape’s :indeed it may very well be the ____________ itself (2016) consists of a series of platforms made of compacted soil, from which holes have been dug out and filled with “emotive objects” — herbs, minerals, bits of clay.

Even works employing industrial materials often seem to suggest — either through context or intention — runic antiquities: vegetable gardens planted in concrete containers and truck tires (Carla Filipe, Migração, exclusão e resistência [Migration, Exclusion and Resistance], 2016); and a pair of towering columns — the largest works in the show — one constructed of stacked logs and straw, the other of bricks, cement and steel (Lais Myrrha, Dois pesos, duas medidas [Double Standard], 2016).

On the ground floor, Bené Fonteles (Ágora: Oca Tapera Terreiro, 2016) exhibits an array of folk objects, statuettes and textiles around a circle of dirt and housed beneath the thatched roof of a clay hut. Not to worry if Fonteles’s hut isn’t your thing; maybe Pia Lindman’s mud and bamboo hut (Nose Ears Eyes, 2016) up on the second floor will be more to your liking.

To be sure, there is work that falls outside of this dream world of craft and nature and primordial return — for example, Hito Steyerl’s video installation Hell Yeah Fuck We Die (2016) on the technology, politics and poetics of robotics. Rosa Barba’s film Disseminate and Hold (2016), funded by the Prix International d’Art Contemporain, examines the Minhocão, a vast concrete elevated highway that runs through central São Paulo, erected in the midst of the military dictatorship. It’s a subtle socially and politically grounded study of built environment.

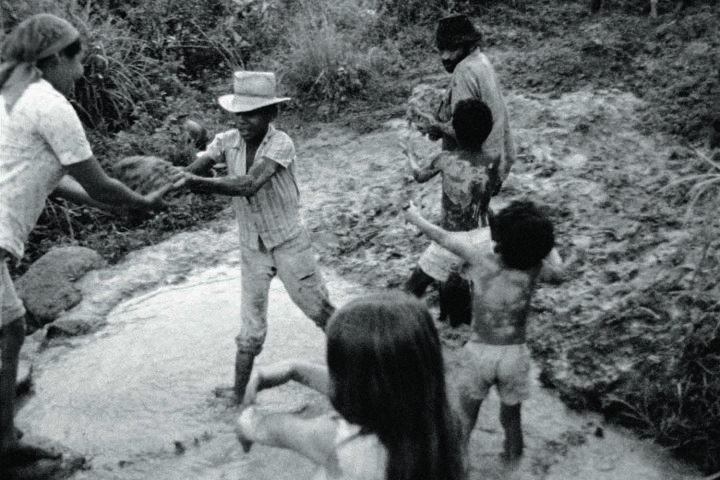

But the overall tone is one of folksy escapism and anti-rationalism, sometimes despite the particulars and conceptual intentions of the artists (even in a couple of my examples above). Works like Leon Hirszman’s Cantos de trabalho (1974–76), beautiful, radical film studies of Brazilian rural laborers; or O Brasil dos índios: Um arquivo aberto [The Brazil of the Indians: An Open Archive, 2016], a selection of the work of Vídeo nas Aldeias, a collective that, for three decades, has trained indigenous Brazilian filmmakers and documented everyday life in these communities, here feel like they are being marshaled away from specificity toward a generalized nostalgia.

Whether another kind of exhibition — one more politically unequivocal or one with fewer mud huts — would have made a difference in the face of Temer’s power grab depends on how one measures the efficacy or purpose of political art. But it raises more questions than just that. Do we misconstrue both when we read an international exhibition against a national political context? Regardless of the political sympathies of the curators (no doubt left of center), and of Oscar Niemeyer’s utopian vision (cultural nationalism and political communism), doesn’t the space of the pavilion in fact belong to the global nowhere of the art world? The everywhere of capital? Yet Brazilian collectors and those on museum boards are drawn largely from the resurgent right-wing ruling class, kept at bay until now by a general contentment with surging commodity prices. Such localized political dynamics were certainly on the minds of Aparelhamento, a group of artists staging direct actions and protests against the coup, and who arrived en masse during the exhibition preview in black T-shirts bearing slogans like Fora Temer [Temer Out] and Diretas Já [Direct Elections Now].

As for uncertainty… that, of course, is reality. And it might not so easily be divorced from fear. In the US — maybe you’ve heard? — we have our own monster waiting in the wings (and a lesser evil stage left). But in art, uncertainty is a long-standing preference. We want everything to be destabilizing, defamilarizing, nonbinary, ambiguous. What, I wonder, would an art of certainty look like, one that, “in order to objectively confront the big problems of our time,” relied on conceptual categories like right and wrong?

Back at Unique, things were pristine, while the zombies continued to linger on the sidewalk. Later I found out they were waiting for autographs. Rammstein was staying at the hotel.