What catches my eye first upon landing at Ben Gurion International Airport, and after having been asked twice if I hold an Israeli passport, is a selfie station with sand and a fake background of tourists playing matcot, the popular Israeli paddle ball game.

Back in the 1990s, when my siblings and I would visit our family in Israel, we would play matcot all day long on the beach. Our grandma used to watch us — she would sigh and complain, with her inimitable Ashkenazi sense of humor, that Israel is just a great country to dry laundry outside.

The shuttle takes me directly to Jerusalem, where I am on the jury for Zoom, a newly founded art prize that distinguishes one young Israeli artist each year. Many of the finalists address their own identities as Israelis, living in a complex country with controversial politics. Some of them are Mizrahi or Sephardic or Palestinian, and their works question how to exist within an Arabic culture in a country at war with Arabs. This year’s prize recipient, Dor Zlekha Levy, mentions Andalusia as an example of a moment and place in history when Muslims, Christians and Jews lived together in peace. One of his videos depicts a Jewish cantor wearing a kippa and performing, in Arabic, a song by the iconic Egyptian singer Abdel Halim Hafez. Later that night, a performance in the garden brings on stage a charismatic Palestinian singer dressed in a full black hijab and heavy makeup, rapping like a goddess. My head suddenly feels a bit dizzy — is it the memory of a scene in East Jerusalem this morning, when I tried to enter the famous Al-Aqsa Mosque, which I had visited a few times as a teenager, and was told that access has now been banned for non-Muslims?

The next day Tali Cherizli, the director of Artis, takes us for a Bauhaus architecture tour along Rothschild Boulevard. “It is our Strasse,” she says, with a smile. The buildings are stunning, and their concrete rigidity blends beautifully with the palm trees planted along the road. The Jewish architects who fled Nazi Germany in the 1930s brought with them the Bauhaus prerogatives of functionality and accessibility, some principles that perfectly fit the original socialist ideals of the Jewish state. At lunch at the Tel Aviv Museum restaurant, a delicious labne with za’atar, the traditional Middle Eastern yogurt topped with thyme and sesame, reminds me how much I’ve enjoyed the food while traveling in Israel, Syria and Lebanon. I think about Beirut and realize how much cultural dynamism, criticism, and feeling of constant tension link the Lebanese capital to Tel Aviv, and how inconceivable it is to imagine that a young Israeli will never be able to visit Beirut, and neither a young Lebanese, Tel Aviv.

In the afternoon, the taxi takes me to Bat Yam, a suburb of Tel Aviv rapidly developed in the 1960s to absorb the flow of immigrants coming to Israel. I indicate to the driver the street where my grandparents lived after they were expelled from Poland in 1968. I find the front door, but realize that I’m unable to read any of the current inhabitants’ names in Hebrew. I sit on the sidewalk and try to picture what was on my grandparents’ minds while they strolled along the modest streets of Bat Yam — after leaving behind the elegant houses of Warsaw. Did they sometimes miss the lush winter snow of the city they knew they would never see again?

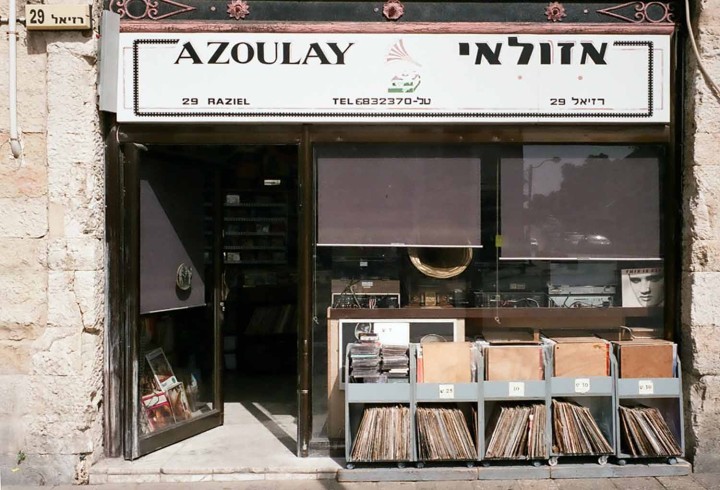

At a café in Jaffa, I meet with Eyal Sagui Bizawe, an Israeli filmmaker of Egyptian origin who produced The Arab Movie, a documentary on the tradition of broadcasting Arabic movies on Israel’s Channel 1 every Friday afternoon, before Shabbat. How far are we now from the multiculturalism of the region in the 1920s through ’40s, when countless famous Egyptian musicians and dancers were actually Jews, and casually traveled between Cairo, Tripoli, Jerusalem and Damascus? I walk around the neighborhood and stop by Azoulay, one of the best record stores in the country if not the region, established a few decades ago by Moroccan immigrants who missed Arabic tunes so much that they decided to start importing music from all over the region, also producing the work of Israeli singers.

Back at home in Los Angeles I listen to the remarkably produced LPs of the 1970s Israeli folk-funk singer Grazia, alongside tracks by musicians Googoosh, Selda Bağcan and Fairuz. Every day I am reminded that they (we) have far more in common than that which divides them (us).