The autumn setting sun merges with a flow of lights over the dry California desert as we drive into Las Vegas. It is a Saturday in November, and the distinctive voice of young rapper Rich The Kid is blasting: “I buy you diamonds, buy you diamonds.” We stroll along Caesar’s Palace, the shiny Eiffel Tower, and golden Trump Tower.

We’re staying in Downtown Vegas, a once-bustling historical part of the city surrounded by older casinos and modernist neon signs. At the blackjack tables of the Golden Nugget, I witness a sparkle in the dark blue eyes of artist Ed Fornieles as his turn to bet approaches, reminding me of Viennese writer Stefan Zweig’s striking 1927 short story “Twenty-Four Hours in the Life of a Woman.” The novella traces an English widow through a single day as she becomes mesmerized by the almost suicidal, reckless gambling of a young Polish diplomat she spies one evening in Monte Carlo. From this first spark of interest, she is drawn into his troubled, unstable life, and ultimately, the unflinching depiction of his obsessive addiction.

The next morning, we head back to the Strip. A world capital of gambling, Las Vegas was originally not only supposed to imitate amusement parks, but also to conform its urban appearance to the playful desire of its tourists. In the 1990s, as Vegas was becoming a common destination for American families, the Strip, technically a four-mile stretch of Las Vegas Boulevard South, became a public theater of reproductions of famous architectural landmarks, such as the Luxor’s Sphinx and the Venetian’s imitation of the Italian city. Their baroque displays provide a kaleidoscopic, vertiginously seductive effect. As we walk into the Venetian, its fantastical, artificially backlit real canals and fake Italian sky make artist Jesse Stecklow comment that it might be the best work of art he has seen in a long time.

Later that day, a panel titled “Think Vegas” — a discussion of the artistic potential of the city, its visual history, economic development and transactional experiences — takes place in the context of the opening of an artist residency at the Plaza Hotel, developed by the London-based Zabludowicz Collection. As I try to concentrate on the almost exclusively male panel (sometimes referred to by female writers as a “manel”), I keep recalling my favorite scene in Terry Gilliam’s 1998 Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, based on the eponymous novel by Hunter S. Thompson. Lucy, played by Christina Ricci, is tripping on acid and showing Duke and Gonzo her numerous portraits of Barbara Streisand in her pink hotel room. Interestingly, that same afternoon, art historian Libby Lumpkin, who also started Vegas’s very first private art collection, Steve Wynn’s at his Bellagio Gallery of Fine Art, emphasizes the role of art institutions and public education versus private initiatives. If Vegas is a city of winners, is there room for any type of failure, an element so inherent and relevant to the creative process?

The next morning we drive into the desert to visit Michael Heizer’s installation Double Negative (1969–70), which consists of a 1,500-foot-long trench in the earth, created by the displacement of 200,000 tons of rock. The work essentially consists of what is not there and what has been displaced, and the immense void brutally contrasts with the sound and fury of Vegas. Upon our arrival on the site, artist Jon Rafman asks in laughter, “ Is it land, or land art?” I recall how Nevada, America’s principal on-continent nuclear weapons test site from 1951 to 1992, has often been considered a suburb of Los Angeles.

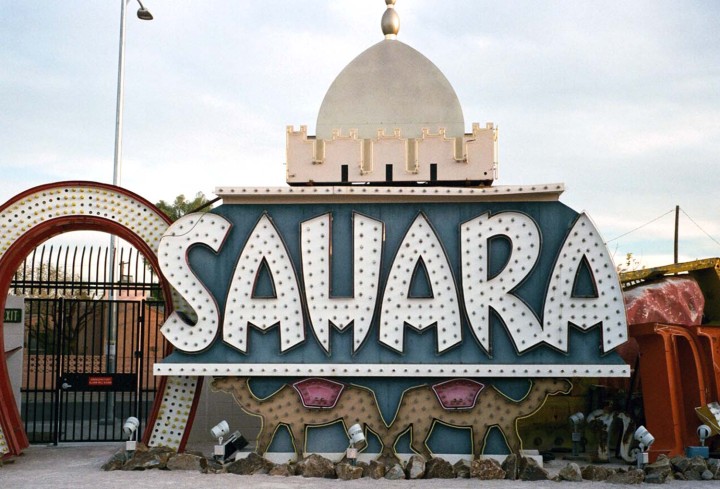

It’s no surprise that we find no contemporary art museum in Las Vegas. We end up at the Neon Museum, a cemetery of vintage artifacts and piles of old signs that testify to the visual heritage of the city. In their infamous 1972 essay “Learning from Las Vegas,” Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi analyze how commercial and popular architecture, in its exuberance and expressivity, has fundamentally shaped American popular culture. They call for architects to be more receptive to the tastes and values of “common” people and less immodest in their erections of “heroic,” self-aggrandizing monuments. The most striking of the old Vegas neon signs reads Sahara, and resembles the entrance of an Arabian palace, if not a mosque, surrounded by two glorious glass camels. During the same weekend that an American business magnate, the owner of the tallest golden hotel in the city, claimed that Muslims should be banned from entering the U.S. — the same weekend that the French far-right nationalist and anti-immigration party Front National has prevailed in the first round of regional elections — I’ve fallen for this abandoned, broken, lush neon of Middle Eastern influence. Vive le Sahara!