For emerging Southeast Asian art scenes striving for recognition within the international landscape of contemporary art, Venice is obviously a major focal point. Southeast Asia had little involvement with the Biennale until 2000. Since then, Southeast Asian artists have been gradually invited to participate in the various curated sections, and, for the past decade, Singapore, Thailand and Indonesia have had solid representation with their own national pavilions.

At the 2015 Venice Biennale, a number of Southeast Asian national pavilions showcase outstanding artists and curatorial concepts. Yet recent cancelations, decades-long hiatuses and debates over fraught selection processes have revealed complex mechanisms still at play, and bring questions of national representation and cultural diplomacy to the forefront.

For the first time in fifty-one years after its one-time participation in the Biennale’s 32nd edition in 1964, the Philippines returns to Venice. Following a rigorous selection process, art historian Patrick Flores’s project “Tie a String around the World” was chosen by a panel of jurors out of sixteen submissions. Commissioned by the National Commission of Arts and Culture, Flores told Flash Art: “I think the government has realized that a Philippine presence in the global contemporary art scene is a timely response to the robust ecology of the local art world. This is way to offer a platform for that ecology to further thrive elsewhere.”

Developed out of prior research, the installation at Palazzo Mora explores the first film ever made about Genghis Khan — an early 1950s collaboration between Filipino artists Manuel Conde and Carlos Francisco. Flores chose two contemporary artists to work with this premise: Manny Montelibano and Jose Tence Ruiz. “I thought that the former’s video work and the latter’s installations responded well to the theme I was trying to cast,” Flores said. The project both speaks to the country’s current predicament in the South China Sea and offers a broader allegory about world making and the notion of possession. By choosing artists from different periods in history, from the 1950s through to the 1990s, Flores also attempts to introduce viewers to the history of modernity in the Philippines.

Singapore, on the other hand, has taken part in the Biennale since 2001; particularly successful projects include Ming Wong in 2009 and Ho Tzu Nyen in 2011. Singapore was absent from the 55th edition due to its participation being under review by the National Arts Council. There was understandable consternation and a momentary loss of confidence from the Singaporean art community, prompting an open letter, signed by some two hundred arts practitioners, urging that the decision be reconsidered. Singapore is now working toward a long-term lease of a pavilion space at the Venice Biennale. David Teh, a Southeast Asian art specialist and also the director of Future Perfect, commented: “Their system for finding candidate artists doesn’t always yield compelling proposals, and after the recent successes, there was apparently a sense that the field was thin. I’m quite sure that was wrong, and while I can’t speak impartially of course, Charles Lim’s pavilion proves it.” Curated by Shabbir Hussain Mustafa and commissioned by the National Arts Council, the highly anticipated pavilion showcases a culmination of the artist’s ongoing series “SEA STATE,” initiated in 2005. Referencing Land Art of the 1970s, the project traces the geographical contours of Singapore as well as its biophysical, political and psychological position through the visible and invisible lenses of the sea.

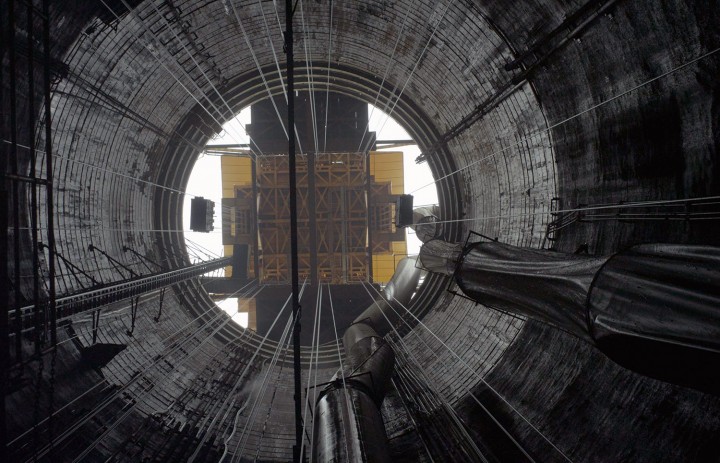

Indonesian artist Heri Dono is exhibiting the site-specific project Voyage – Trokomod at the Arsenale. It is only the second time Indonesia has exhibited in the Arsenale. Coming full circle, Heri was also invited to exhibit in the 2003 “Zone of Urgency” exhibition curated by Hou Hanru, making him the first Indonesian artist to take part in the event since Affandi’s participation in 1954. As with many emerging scenes in Venice, it is often the private sector that leads the way, in the absence of government support. Heri Dono’s project is organized for the second time through the private efforts of Restu Imansari Kusumaningrum of Bumi Purnati Indonesia, an independent legal entity that supports the arts. Co-curator Carla Bianpoen said: “For Imansari and the artistic team whose pursuit for culture is of central significance, it has been an uphill struggle. Cultural diplomacy urgently needs a well-planned and formulated national cultural strategy.” A cross between a Trojan horse and an Indonesian Komodo dragon, the Trokomod rejects Western hegemony and speaks to the plurality of contemporary art today. Bianpoen continues: “Metaphorically the ancient-looking giant Trokomod represents a metamorphosis from the depths of memory, rising up as a futuristic submarine within a spirit that surpasses mere pluralism and equality.”

Thailand has taken part in the Biennale every year since 2003, when Apinan Poshyananda introduced the first Thai Pavilion. Following the exhibition of esteemed Thai artists like Arin Rungjang and Wasinburee Supanichvoraparch in 2013, Thailand’s selection of Kamol Tassananchalee this year resulted in major controversy within the Thai art community. While the senior modernist painter has no doubt been a respected artist in the country for many years, he is relatively unknown on the international contemporary art circuit, prompting questions of whether he is a contemporary artist at all and debate over the opaque selection process. It is understood that the system Thailand had for selecting artists, which was linked to their national Silpathorn Awards, was abandoned this year due to bureaucratic in-fighting within the culture ministry. There has been no satisfactory reason for his selection and, unfortunately, almost no promotion of the project.

National pavilions are, of course, instruments of national representation. Yet the question of artist selection is arguably more loaded in Southeast Asia than in Europe or America. David Teh notes: “Let’s not forget that the governments of this region are predominantly still authoritarian. In many Western contexts, contemporary art isn’t primarily a vehicle of the state imagination. In Southeast Asia, though, many contemporary artists are still preoccupied with problems of national identity — partly because these are complex stories that some artists care about, but perhaps more because institutions and the market have developed identitarian product lines that have sold well on the global stage. So there’s a kind of thematic hangover, and it does affect selection for Venice.”