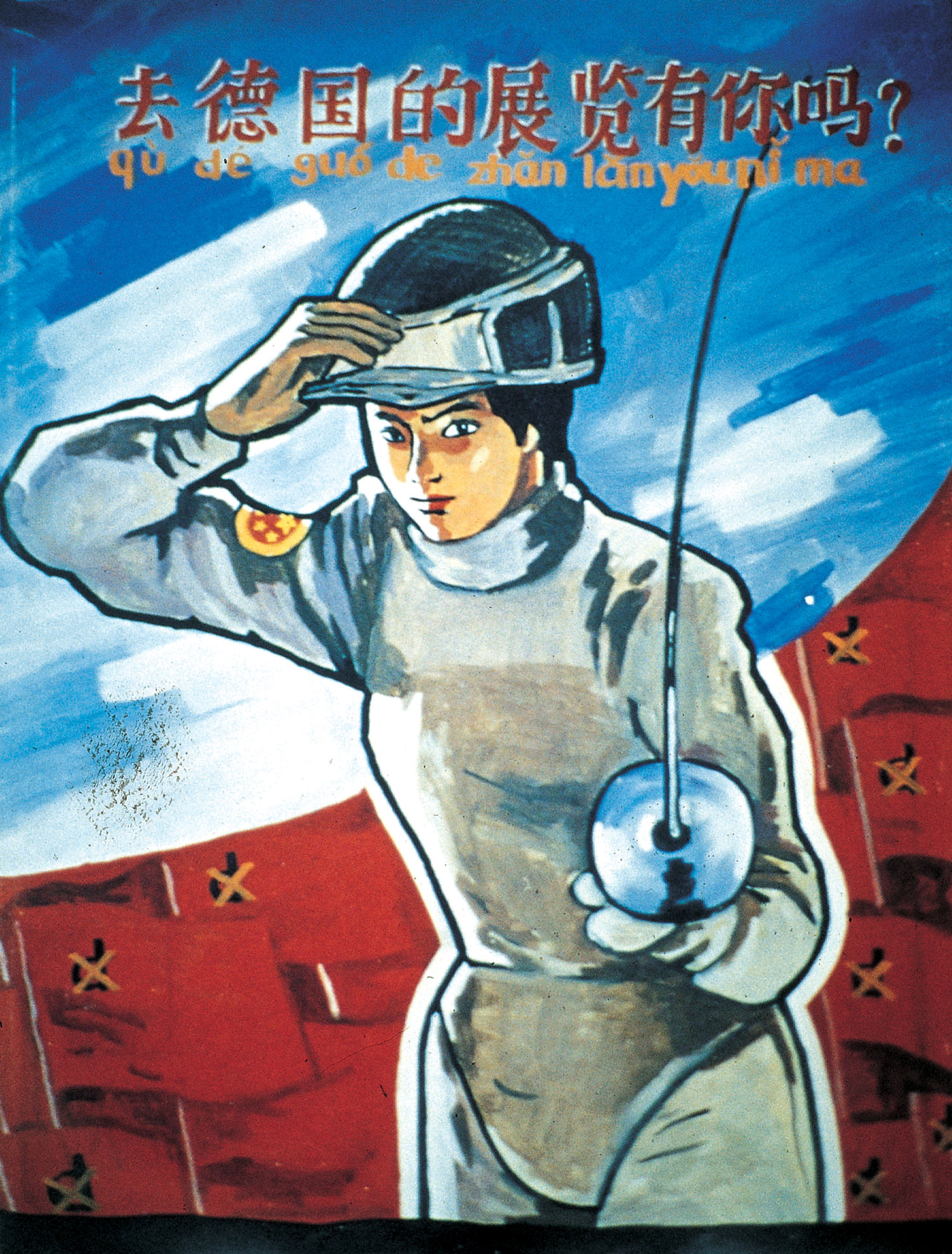

The subject of Douglas Gordon and Philippe Parreno’s new film, Zidane, A Portrait of the 21st Century, is a myth and its contemporary hero: a 34-year-old soccer player who is going to retire. In the previous century, a possible portrait of a hero could be one in which a young man starts his career at the age of seventeen and whose glory continuously radiates thereafter from past exploits. This begs the question of what a hero is today. If men create myths, myths in turn give back to men something to believe in (role models, images, hope); if TV generated a cinema for the masses, it likewise enlarged their domestic perception of the world. A hero accomplishes exceptional feats, goes beyond his limits and becomes a figure “beyond reach.” Formerly, when genres were still valid in art — portrait, landscape and still life for instance — history painting was devoted to depicting heights populated by extraordinary men, who, in achieving their superhuman feats, acquired the status of hero.

The modern hero has therefore become an athlete, such as Robert Musil foretold in his book The Man Without Qualities in the beginning of the 20th century. Today a portrait can be measured by durations of time: ninety minutes, the length of the film and the duration of a soccer game. Zidane, the renowned soccer player, has entered the pantheon of stars; on the big screen he shines above and beyond all others. This screen has replaced the window onto the world, where thousands of pixels have come to define pores of skin. The scrutinizing camera follows a drop of sweat, watching it pearl up and describe the contours of a face as it falls. “Zidane’s talent has turned him into a legend, the purity and aestheticism of his technique as well as his personality have rendered such a portrait necessary,” state Sigurjon Sighvatsson from Palomar Pictures and Anna Lena Films, the film’s producers, in the press release. This is not the portrait of a man, but of a dream shared by many young people and now realized by two artists who want to see their hero up close.

What makes the film special is its technological precision, for example hearing and feeling as close as possible the impact of a foot kicking a ball. Both the film and the athletic gesture share a kindred ambition: to find producers, to imagine and bring into being a certain point of view while using the best possible technology to edit the product, each stage being enacted with precision. Here editing is crucial. It fuses the two artistic attitudes of Parreno and Gordon: “Philippe makes the images, I find them,” says Douglas Gordon. The portrait is not only about the physiognomical features, though Gordon’s penchant for close-ups and facial expressions is well known. From the first kick of the ball until the final whistle, this portrait is made out of the four fundamental expressions of which actors may avail themselves (love, hate, joy, sadness) and as such evokes the theater and the tragic mask, which in Greek also means persona. Beyond addressing the idea of the genius or the hero, this film aims to accomplish a certain task or gesture as well as it possibly can. In this way it allows something rather simple to become transcendental, pushed beyond its limits. This could very well be the challenge of the 21st century: to do it, whatever it may be, until it becomes a work of art.