Beatrice Leanza: Since the mid ’90s your work has consisted mainly of five large series of paintings (“International Scenery,” “Climbing Space,” “Colour Wheels,” “Super Lights” and the triptychs). What do they represent overall?

Yan Lei: They are an interpretation of painting itself and my willful approach to art making, my perplexities, anger and responsive integrity against its value system and power structure. “Climbing Space” is a form of ‘spiritual’ ascension within the art world, which derived from “International Scenery.” In “Climbing Space,” most of the subjects are airports, spatial signifiers of both physical ascension and affordability of social status; together with these are places such as exhibition halls which are connected to my personal professional experience. What they encompass is a form of mental movement voyaged within.

BL: Has this loitering been an accretion or a diminution?

YL: There is no embedded critique in this sense: it is a portrayal of possibilities, an ongoing process with no prefixed destination. I’ll stop when I am tired of it. I last painted one about the New York Armory Show, a platform, for many: all traces of competitive, debateful human relationships are preserved therein. Painting to me has a highly symbolic power too; it is tradition, history and thus material value.

BL: Is that an attempt to advance a critique of the Chinese system or society?

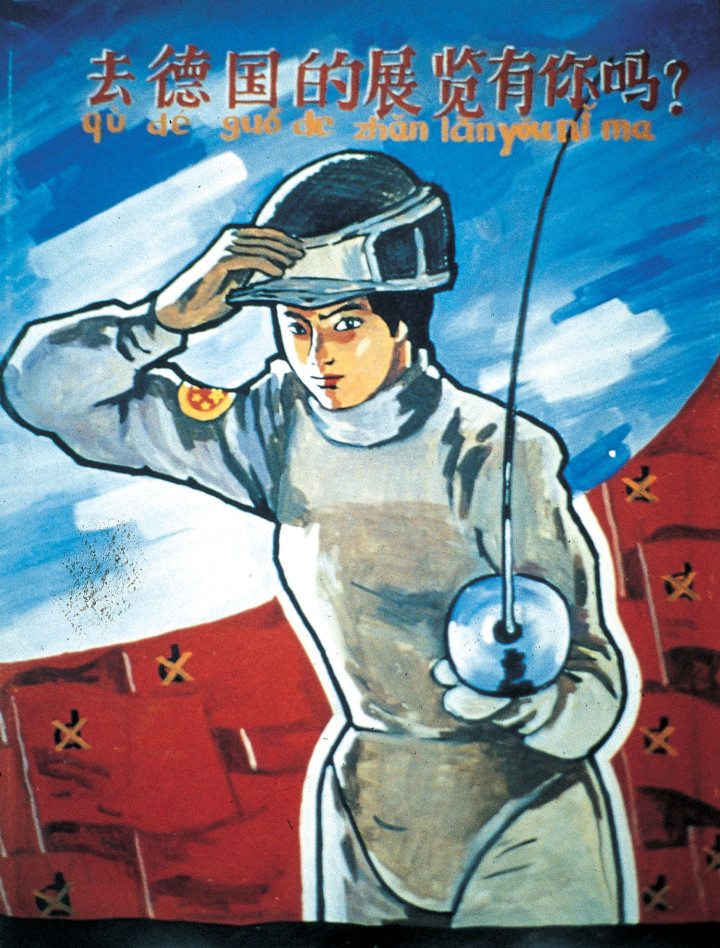

YL: It is a personal response. Since 1996 I did not paint a single canvas. I did the work Are you in the exhibition that’s going to Germany?, thinking about what it meant to be an artist without the standards of this world game. The year after, together with Hong Hao, I produced a fake invitation letter to that year’s Documenta and sent it out to some prominent Chinese artists and art critics. That was the time when the internationalization of Chinese art was reaching its peak: commissioned art production unveiled the meaninglessness of art making itself.

BL: How is the paint-by-number method and the use of color-wheel schemes integrated within your creative process?

YL: People say that I would paint anything. My system of production comprehends a few hundred of colors that I created and then digitally classified according to a ratio by attributing them a number. In color wheels this system becomes clearly visible. The very first one I painted (in 2003) commenced with a black dot; from there the last color circle became the starting point of the next one. All I control is the size of the canvases.

BL: Color is an important structural element in your work: it exposes the pictorial fragility of a personal system ruled by life’s randomness, the endless circularity of a methodological, self-inducted control or rituality.

YL: Colors become sufficient to the work as a way of exploring a representation of my working method. It is in itself a possibility of painting that almost needs no work. In the triptychs series I am connecting painting to a sort of revered righteousness by objectifying it through its materiality (the color cans); the fictitious system that is employed becomes a form of order (the color wheels); and an image (the Buddha) comes to confer status.

BL: You use different images of Chinese artists’ works, both traditional and contemporary as well as some withdrawn from Western art history, or from your everyday life.

YL: I collect certain happenings under peculiar circumstances: for example Dog Year New York, featuring a work by Cao Fei, was realized for my first participation in the Armory show, happening at the same time of Cao Fei’s solo show in New York, and also the presentation of the much-talked-about Sotheby’s Asian art auction.

BL: In 1997 you moved to Hong Kong. Why did you finally come back to Beijing?

YL: I went to Hong Kong to find something new, whereas in Beijing nothing was really happening. But then Hong Kong revealed a great emptiness; the restrictiveness of space turned out to be also a spiritual one. It was difficult to integrate or even find a responsive artistic environment, or a sense of collective belonging.

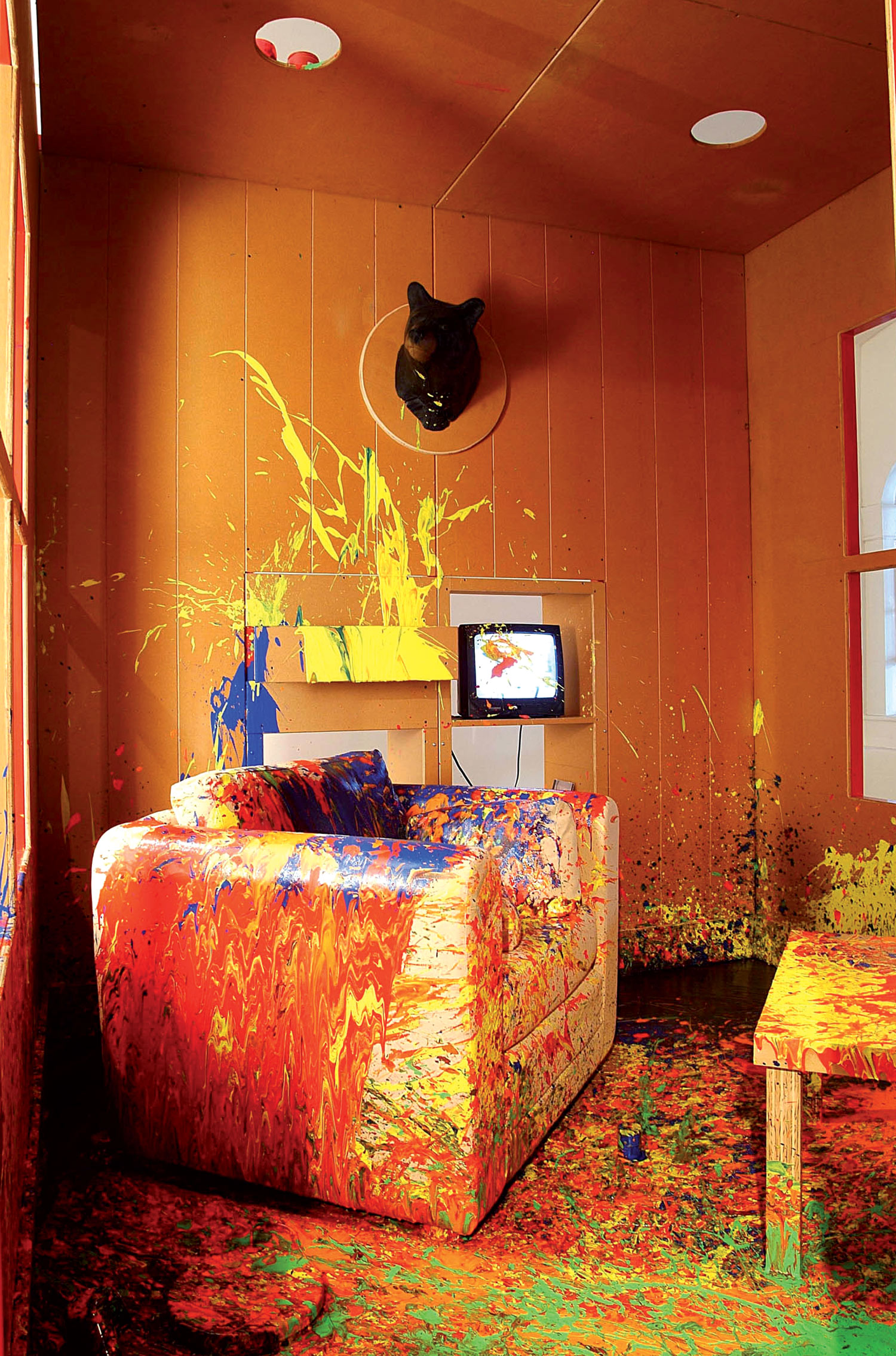

BL: Out of that period you realized two installations (International Passage, 2002, and The Fifth System, 2003). Both address issues of public space and the disposal of power and resources.

YL: The first is a collaboration with Fu Jie. It is a reproduction on a linear plane representing the passage from where we used to live in Hong Kong to the street, modulated on the size of the different intersecting doors into the shape of a long corridor, as the exploration of the transition from a private to a public space. My proposal for the Shenzhen public art exhibition was to entrench a green surface as big as a stadium inside the OCT community and preserve it for two years from developmental speculation. What I am interested in is the process of construction, how this form of materiality is created, and how that resides in people’s consciousness, and their spiritual adaptation to such forms of control.