Art provokes! Sometimes it whispers. On certain occasions it shouts, but it rarely utters the same words to everyone. I still recall the day when one of my college students called me a liar. Not mockingly, not in a, muffled remark. It was a blatant statement, articulated ever so eloquently in front of the whole classroom: “Sir, you are a liar!” The reason? A mere picture, smaller in size than a trivial sheet of A4 paper. What in that artwork could have prompted a twenty-year-old student to insult her tutor? And with such grit? Throughout that week, we had been exploring Persian miniature painting in a course on Islamic art. On that day, I decided to show the class slides of a 16th-century Safavid Shahnameh attributed to Sultan Muhammad, a master painter of that period. The whole misfortune was prompted by an illustration of the Prophet riding his mythical mount Buraq on the night of Al-israa’ wal mi’raaj. It is common knowledge, and a major misconception, that in Islam it has been traditionally forbidden to make any figurative drawings of living beings, let alone of the prophet Muhammad or any other prophet. But that was not the case in Safavid Iran. Due to their rooting in Sufism, and despite converting to Shiism in the mid-15th century, they maintained Sufism’s spiritualist approach to religion, thereby acquiring a progressive and liberal stance on the daily application of religious law: shari’aa. This approach was reflected in all aspects of their culture, including their aesthetic sensibilities. Words such as “unacceptable” and “it can’t be true” were bombarding me from all angles, especially from one girl, the one to eventually declare me a cunning liar. I was now the Antichrist to a bunch of frenzied fanatics who were revoking historical facts, refusing to engage in objective debate and flagrantly accusing their professor of sabotage because of a drawing.

What is it about art that drives us to adopt such adamant stances? Art history reeks with such examples. During the Second World War in Nazi-occupied Paris, a simple Louvre curator risked death on a daily basis while spying on the German troops. The Nazis took photos of all the art they were stealing and confiscating, which they then stored at the Jeu de Paume. Every night, in order to create a reliable inventory to be used as crucial evidence later on, Rose Valland would smuggle the negatives out of the museum and make copies of them. During the day, she would resume her duties at the museum looking after the maintenance staff and watering the plants. Her actions could have resulted in her being immediately shot or sent to a concentration camp.

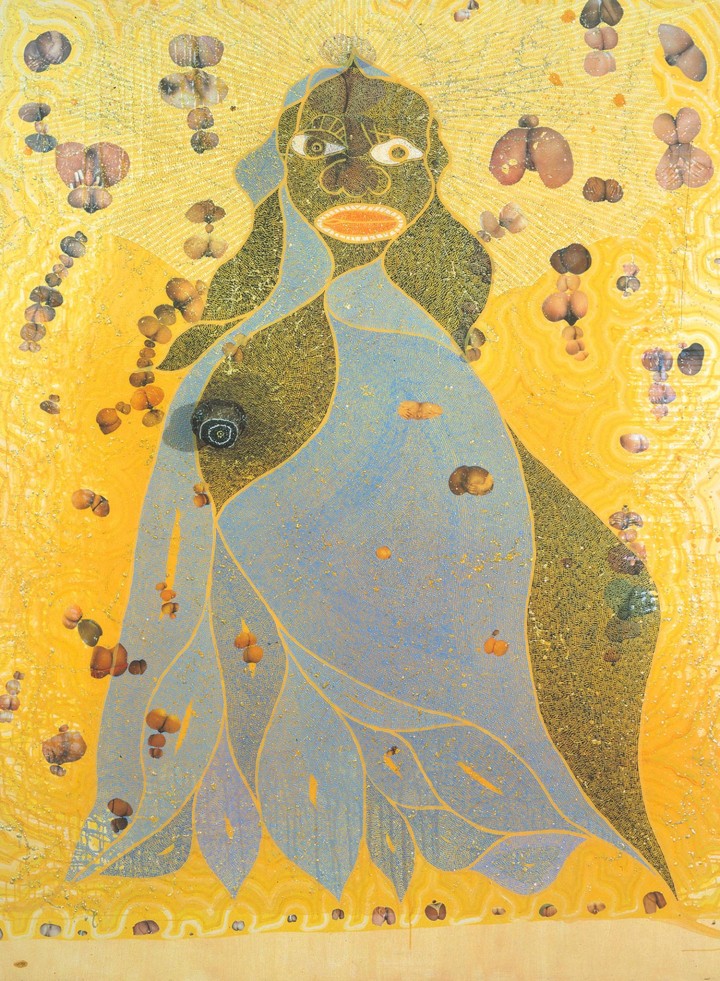

In 1996, Chris Ofili, a British artist of Nigerian descent, incorporated elephant dung into his painting The Holy Virgin Mary. In 1999, Dennis Heiner, a 72-year-old retired schoolteacher, sneaked into the Brooklyn Museum where the work was on view and thrashed it with white paint. More indignation from various factions prompted Rudy Giuliani, New York City’s mayor at the time, to wage a court battle against the museum, asking for immediate closure of the exhibition and the withdrawal of public funding. The city lost and was instructed to pay a further US$ 5.8 million to the museum.

On May 7, 2004, the whole world was shocked by the assassination of Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh (a descendant of Vincent van Gogh). It was his film Submission that provoked this violent reaction. Written by Ayaan Hirsi, an ex-Muslim Somali refugee who became a Dutch parliamentarian, the film features images of semi-naked women with Koranic verses written on their skin. Drawing from her past experience, Hirsi wished to expose the abuse of women in certain Islamic societies.

I could go on, telling story after story of ordinary people made heroes or villains by art. How you choose to define them depends on whether you share their opinion or not. And if you do, the question would be: Does the end justify the means?

When a work of art manages to involve you, to aggravate you, you will certainly find yourself reacting. You’re in the domineering presence of an autonomous identity that could either be the embodiment of your most sacred values or their potential “Terminator.” The truth of the matter? Art is a mirror. That which you behold is nothing but a reflection of who you are. And sometimes we don’t like what we see.

When art challenges you, and shakes your comfort zones, how will you debate with it — and ultimately with yourself? For some, prejudiced censorship, vandalism, oppression, even murder seem to have been a lawful option. Luckily, and I am one to be grateful for it, the majority of us find enough consolation in being called names, in my case a liar. By the way, if you are wondering what happened to my student, no, I definitely did not fail her. I just did what everybody else seems to be doing these days: I simply told her to blame it on Iran!