If you Google image “figural,” you’ll see thousands of images of Disney keyring dolls, mostly made of foam. Since abandoning my childhood dolls that I remember styling, or mutilating, depending on my mood, I find dolls grotesque, and almost unethical: so unreal they are almost real. It’s like browsing fake Louis Vuitton bags on Canal Street: you know it’s a fake, but you want it anyway. In fact, you need it, like little kids dragging their plastic pets across the floor, knowing there are stories inanimate objects tell that animate subjects would rather ignore.

It is in this sense that artist Tau Lewis’s doll-like figures make the known feel strange, and the strange feel known. At Frieze New York this year, Toronto’s Cooper Cole gallery, which won the 2018 Frame Prize for its presentation, exhibited a posse of Lewis’s creatures. “I’m bringing a series of portraits that are also my friends and feel very real to me. The figures are physical manifestations of a deeply healing process. They are magical and unreal and unbelonging, and they help me work through collective and personal traumas. We are all excited to be here,” she told The Art Newspaper in May. “Earnest Lewis King” (2017) poses on the floor like an obstinate supermodel with a tail, knowing the scene is watching. Another figure wears a bucket hat and sits in a rocking chair, seemingly mid-swing, and holds a doll of her own. Yet another—a 2018 piece called “Unity (Negros Historical Information Systems in Every Dark Corner)” that floppily sits on a wooden chair—is a flexible paranormal being protruding with eight bulges made of hand-sewn fabric, fur, and leather, coming together as what seems like six arms and hands and two legs. Is a body in bad form still a body? Its gaze, if you can call it that, is vacant, framed by two human ears, and two bear-like ears. Whatever these things are—human, animal, magic, or art—they are tired of being asked, “What are you?”

Lewis was born on October 31, 1993 (a “Halloween baby,” she once called herself), making the creep factor to her art feel almost innate. But her practice is more than trickery: everyday objects hold histories of violence, as well as many other forms of social and material relations. If black people, under the terror of transatlantic slavery, were considered commodities, what else haunts the history of the human? The liberal notion of the universal human still indexes a specific kind of empowered and self-assured individual that, at least in Lewis’s world, does not exist. In every interview, Lewis, who is a self-taught Jamaican-Canadian sculptor and journalism school dropout, makes the thematic of her work perspicuous: black identity.

Today, a hyphenated nationality such as Jamaican-Canadian is said, in print and behind the podium, to be tolerated, and yet is still bound by the vicious rigamarole of citizenship. If you’re not from Canada, you have inherited certain myths about the country, a site of fantasy, and they’re so boring I deign to repeat them here: polite, liberal, diverse. If you’re from the Great White North, and if you’re black, however, you live as Lewis does: by telling your own stories with what you have, when you have it. Lewis is based in Toronto, a city often blindly touted as one of the most multicultural in the world, despite racist inequalities. The landscape of the city is not only a theme in Lewis’s work but a physical requirement. Her sculptures gather stuff from the city: chains, paint cans, pipes, toys, hair, stones, copper, fabric, wires, acrylic plaint, plaster, and her old clothes. Also, stuff not easily associated with the city but found there nonetheless, like sea shells, stones, and bark. And also: some secrets. (She hides things inside of some of her works.)

The last person someone interested in art should talk to is an art teacher but school is a good litmus test of canon formation, that is to say, how a society wills to represent itself. And a teacher of Canadian art will, without fail, mention the Group of Seven—either with regret or enthusiasm. Remembered as originating Canadian landscape art, the Group of Seven (a group of, you guessed it, seven artists), working in the early 20th century, painted the sublime through the representation of clouds, lakes, snow falling, and pine trees. A key figure of the Group of Seven, Lawren Stewart Harris is quoted as having said, “We are on the fringe of the great North and its living whiteness, its loneliness and replenishment, its resignations and release, its call and answer, its cleansing rhythms.” Harris was comparing the art of the United States to that of Canada, where there might emerge “an art more spacious, of a great living quiet, perhaps of a certain conviction of eternal values.” The serenity of such spacious wilderness, however, comes from a history of white settlement. And yet the “whiteness” Harris mentions is often suggested to refer to snow only.

Lewis belongs to a group of black Canadian artists who aren’t really talking about whiteness at all, but about themselves. The question is how to work with the entrenched Canadian narratives to ultimately work against them by putting forth a counternarrative. In Frontiers: Essays and Writings on Racism and Culture, a 1992 collection by poet and writer M. NourbeSe Philip, who was born in Trinidad and Tobago and lives in Toronto, outlines the problem:

I carry a Canadian passport: I, therefore, am Canadian. How am I Canadian, though, above and beyond the narrow legalistic definition of being the bearer of a Canadian passport; and does the racism of Canadian society present an absolute barrier to those of us who are differently coloured ever belonging? Because that is, in fact, what we are speaking about- how to belong- not only in the legal and civic sense of carrying a Canadian passport, but also in another sense of feeling at “home” and at ease. It is only in belonging that we will eventually become Canadian…

How do we lose the sense of being “othered,” and how does Canada begin its m/othering of us who now live here, were born here, have given birth here—all under a darker sun! Being born elsewhere, having been fashioned in a different culture, some of us may always feel “othered,” but then there are those—our children, nephews, nieces, grandchildren—born here, who are as Canadian as snow and ice, and yet, merely because of their darker skins, are made to feel “othered.”

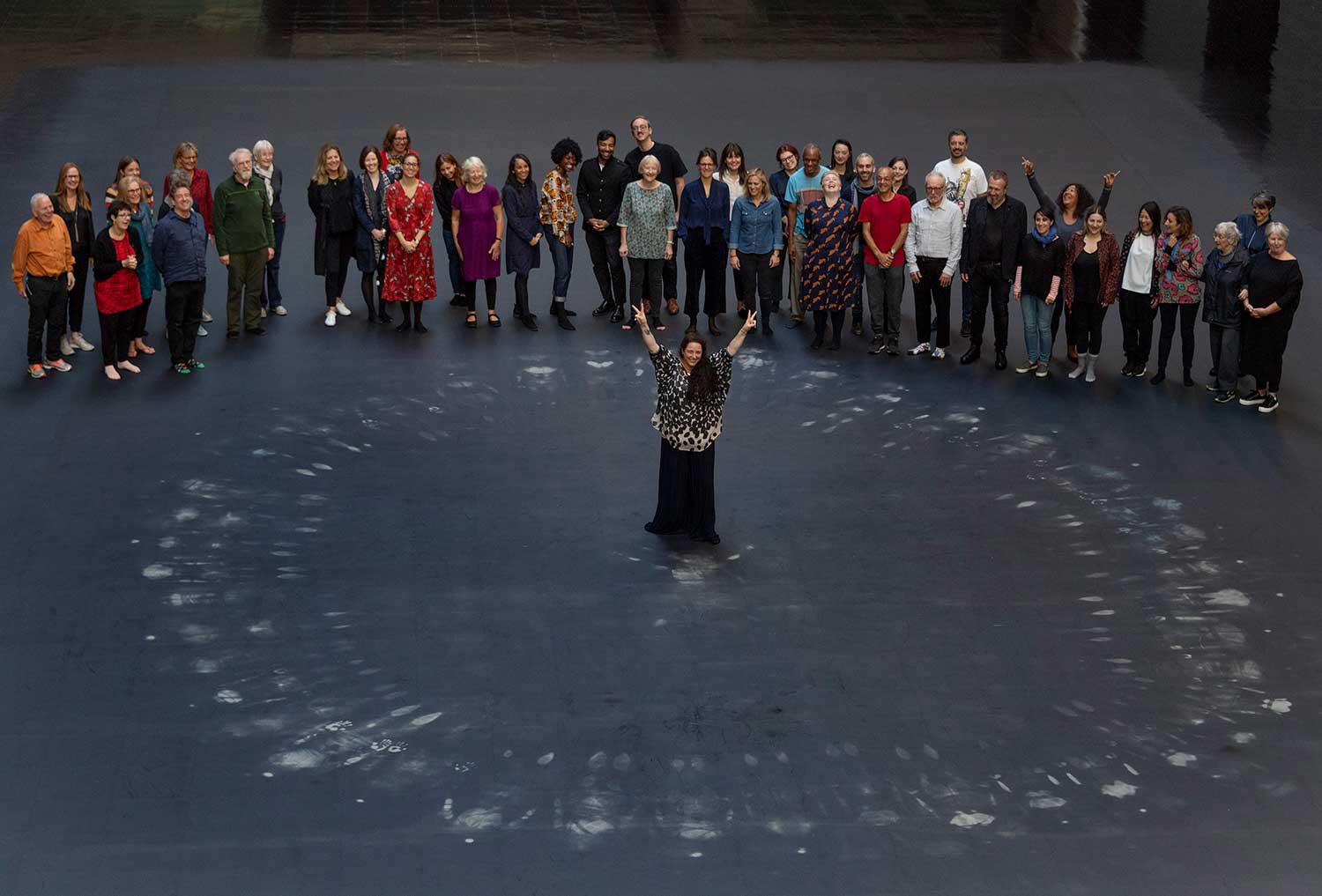

This past summer at Mercer Union, a non-profit art space in Toronto, a collective of queer Caribbean artists, RAGGA NYC, put on a group show, in which Lewis participated. The artists presenting, which also included Canadians Oreka James, Aaron Jones, Michèle Pearson Clarke, Camille Turner, and Syrus Marcus Ware, are that next generation that Philips speaks of: the children and grandchildren of black immigrants who yearned for a sense of belonging. It is as though today, however, belonging to some greater Canada, however seductive, remains a concern of the past.

This does not mean that Lewis disavows Canada—far from it. Rather, it means that being part of the national body politic is not a politics. It is as clear as ever that the Canadian multiculturalist future, enacted by the liberal policies of the 1970s and 1980s, never arrived. In the 2006 book Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle, Katherine McKittrick lists a number of supposed surprises that plague the whiteness of the Canadian imagination including “black women in Canada,” “black resistances,” “slavery in Canada,” and Canada as a site of permanent black residency.” These things, she writes, “are not ‘Canada,’ are not supposed to be Canada, and contradict Canada; they are surprises, unexpected and concealed.” Responding to the erasure of what McKittrick, Lewis and others refer to as “black Canada” within the history of Canadian art, Lewis uses the materials of the Canadian landscape, of which an urban space like Toronto is a part, to construct her figures by repurposing waste.

Lewis’s sculpture practice orbits portraiture. A 2016 work “Everything Scatter (Army Arrangement)”—a title that cites Fela Kuti—consists of a bust mounted on a cinderblock, made with a plaster casting of a friend’s face, wire, soil, paint can, a Christmas cactus, and other materials. The face, perched on the paint can, feels more like a mask than a face. There are parts that seem familiar to a human figure—the plant leaves as hair, the paint can as the neck, or the chain as the skull—and that’s what makes it strange: the familiar presents itself unfamiliar. A similar practice of defamiliarization exists the other way, too, showing how non-human objects contain vitality and life. For example, she told Canadian Art magazine in 2016 that “the cacti probably has the most symbolism in my work. I frequently use cacti to talk about diaspora and black identity. They’re tropical plants that come from really hot climates and they’ve been super domesticated and can survive like anywhere in the world. They also grow, like, really prickly spines that sort of act as preservation tactics.”

Since a 2016 show, “foraged ain’t free,” which focused on busts, Lewis’s work has increasingly featured full-body plaster figures. On Lewis’s Instagram, you can find them posing with her friends, on little chairs, cozied up for bed, half-painted in her studio, cradled by Lewis herself, and getting serenaded by Toronto-based singer Charmie and her acoustic guitar. Unlike paintings, or other artwork stuck to the walls, sculptures provoke an immediate kind of intimacy. With three dimensions, they live among us, in the middle of a room, a gallery. You can walk around a sculpture and breath it in. Still, the most intimate relationship to the work might be the artist’s own. “I secretly hate it when my work sells,” she told Canadian magazine Flare in 2017. “They may be inanimate, but they’re very real to me. I have a really hard time letting them go.”

At the same time that she might inadvertently wish against her own financial success, she seems to be working very hard. Her first museum solo exhibition, “when last you found me here,” is currently on view at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre in Kingston, Ontario. Here and elsewhere, Lewis’s figures follow the contours of an African diasporic condition, a visualization of what Brent Hayes Edwards has theorized as décalage, an untranslatable French word that indexes the very asymmetries that bind us.