Olivia Erlanger politely asks me to hold the call while she scrolls diligently through her screen cap folder. The lengthy silence that follows attests to the sizeable archive, newly expanded by the flurry of unexpected reactions to her most recent sculptural outings, but she repeatedly assures me that the image will be worth the wait. Lo and behold, it decidedly is when it materializes in my text messages a few moments later: a screen grab of an effusive DM accompanied by a picture of a tattoo modeled after one of the silicone mermaid tails initially displayed at a laundromat down the street from the Los Angeles project space Mother Culture in September 2018. “It’s not necessarily about me or my art or my practice,” she adds with a tone of curiosity. “It’s more like this particular sculpture has generated its own fans and has a public life that’s independent from me. I find that distinction really interesting.”

While some artists fastidiously monitor the discursive parameters through which their work is filtered and framed, Erlanger seems more than happy to embrace these types of unexpected and oftentimes rhizomatic deviations. In fact, they might be as generative and constitutive of the practice as the base matter itself. Case in point: the series began as a funny misreading when a friend’s toddler was playfully asked to choose a favorite work at the opening of her 2016 New York solo exhibition “Dripping Tap.” The child paused before pointing to the twin, forked-tongue sculpture Slow Violence and gleefully exclaimed: “I love the tails!”

“That stayed with me,” notes Erlanger. “I loved the idea of these protrusions as shape-shifters. It resonated with the research I had been doing on the status of women’s bodies and domestic spaces. All of these mythical chimeric figures but also a woman with her head in the oven…”

It is worth pausing here and noting that research forms the core of Erlanger’s larger intellectual project; it both animates her wide-ranging output — from sculpture and installation to writing and filmmaking — and supersedes it. Specifically, it’s her sustained and open-ended investigation of American postwar suburbia: its material roots and development, its objects and accouterments, its architectural legacy (such as the advent of the attached single-car garage), its gender and racial divides, as well as the unseen power structures, fantasies, and projections embedded therein, which remain lodged within our cultural imaginary. Since 2013 this undertaking has unfolded as a protean impulse and yielded manifold physical manifestations.

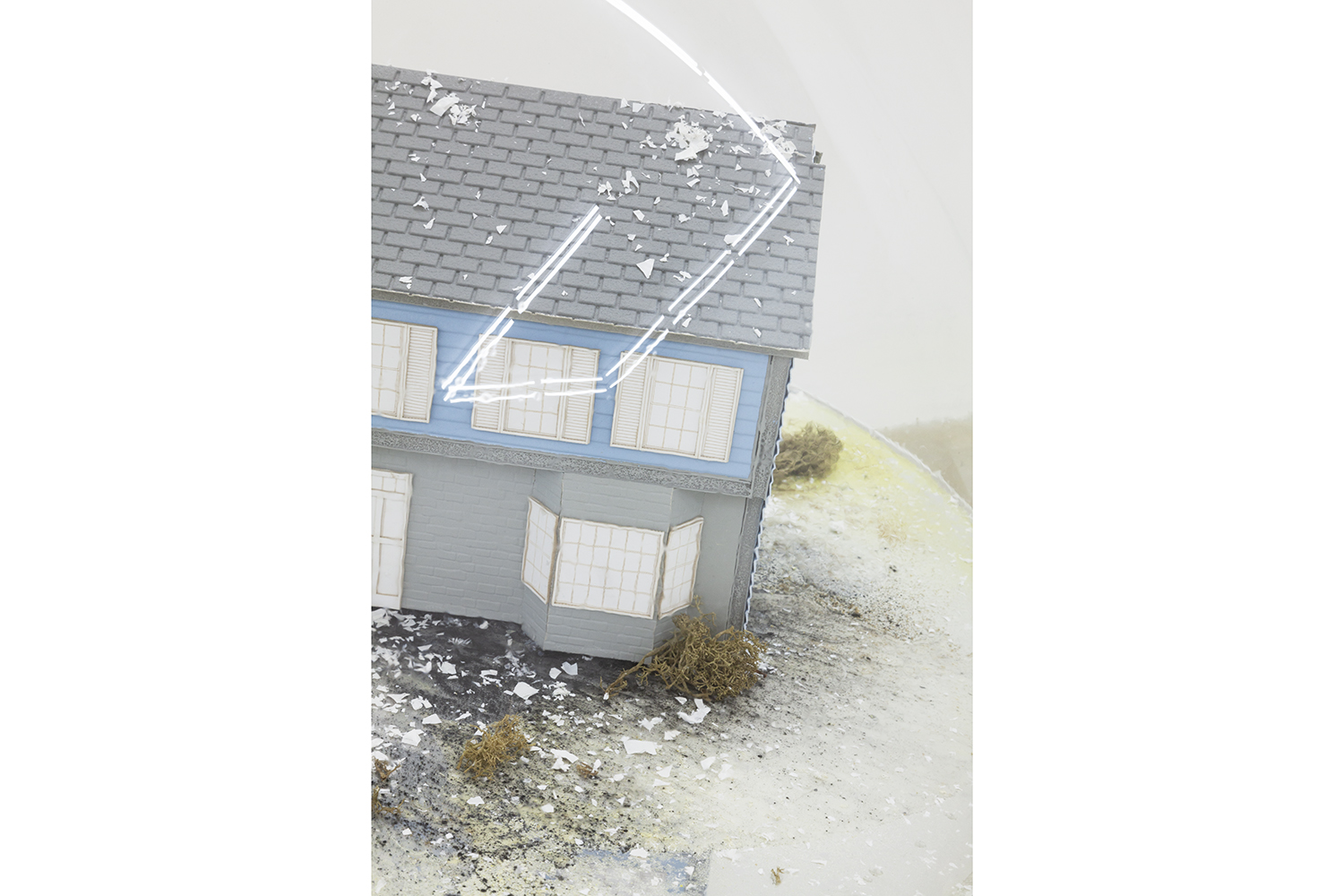

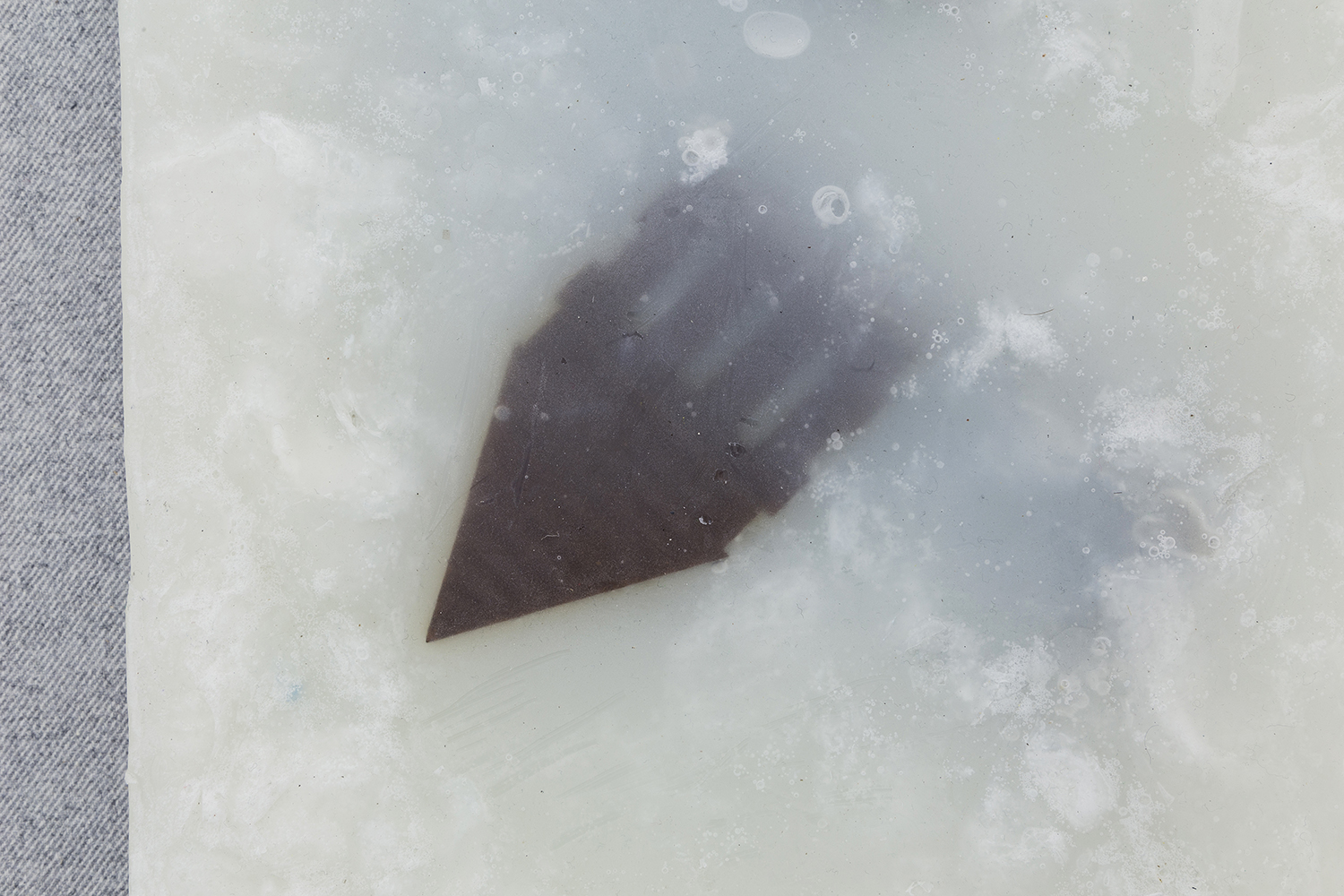

These include discrete exhibitions, such as 2015’s “Dog Beneath the Skin,” which traced the lineage of totemic middle-class objects, from the Victorian parlor piano to the modern garage door. Following the same historical thread is 2016’s “The Oily Actor,” in which modular sculptures evoke the floor plans of prefabricated model homes. Bringing together a wide array of highly symbolic materials (from felt to pollen), the pieces map out an allegorical topography of the forces that converge around the contemporary housing market — from the micro to the macro. The resulting edifices are at once imposing and tenuous, underscoring the fissures where aspirations meet material limits while foregrounding a sculptural logic that is associative rather than descriptive, linguistic rather than purely optic. One corner nook nestles a large slab of shea butter embedded with mini-maquettes of a manor-like home. The ghostly outline appears as a greasy fossil; when pressed it reveals itself as a miniature of Wyndcliffe Mansion — the palatial nineteenth-century home erected in Rhinebeck, New York, for socialite Elizabeth Schermerhorn Jones. Sparking a wave of imitators in the surrounding area, the home is credited with coining the phrase “Keeping up with the Joneses,” which continues to have currency to this day.

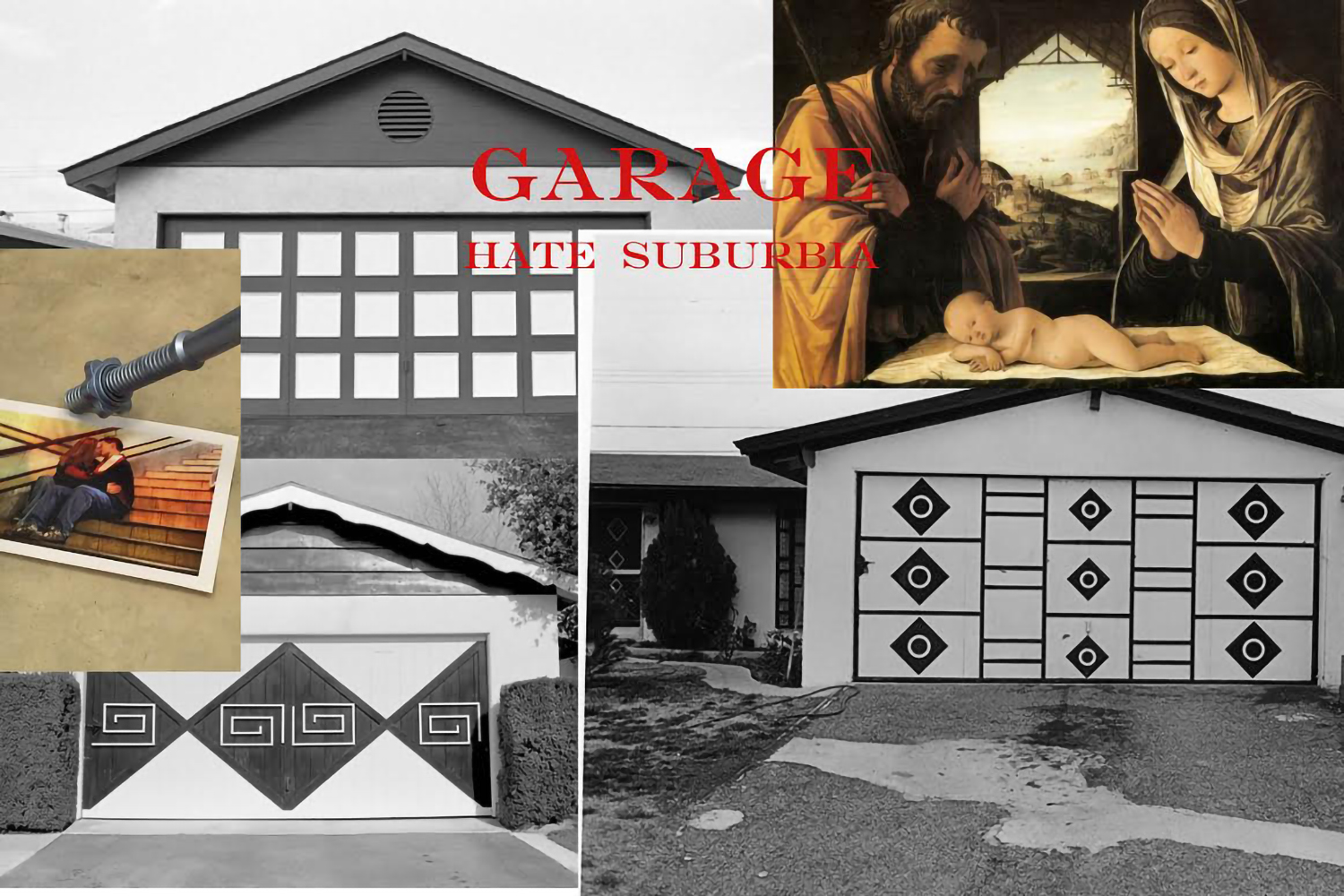

Sometimes these historical threads define the parameters of immersive environments such as Body Electric, developed for

Frieze London in collaboration with BWM’s Open Work in 2017. Featuring video, a reactive soundtrack, and a fluctuating light system, this durational sculpture traces the vicissitudes of the luxury car — the ultimate middle-class status symbol — in relationship to a live and interdependent global oil economy. This automotive shift might have also anticipated the publication of Garage (MIT Press, 2018), co-authored with Luis Ortega Govela. This critical tome traces the evolution of the humble home appendage from its initial design by Frank Lloyd Wright to its near mythic status in the 1990s and early 2000s as a crucible for American ingenuity, from garage bands to start-ups. This project has itself undergone its own transformations, spawning a series of lectures and being adapted by Govela and Erlanger into a full-length future documentary and individual chapters available through the viewing platform DIS.art.

Elastic and constantly permutating, this wide spectrum of activities vacillates between contingency and material specificity. In doing so, it also attempts to circumvent the trap of didacticism by posing forth material propositions rather than crystalized resolutions. This questioning is unruly resulting in its own chimeric guisesbut in so doing I also tests out new positions for the role of sculpture in our contemporary world. How is it received and consumed? How can it be read? What spaces can it occupy? And, perhaps most alluringly, can it reach out beyond the insular bounds of the gallery world? It is a sustained working through more indebted to the associative interventions of the Surrealists than the structured semantics of relational aesthetics. It also remains conscious of its own baggage.

Much of this informs the exhibition “Ida,” which introduced the now-infamous series of mermaid tails and was originally slated for the “main” space of Mother Culture, the art incubator/gallery founded and run by Milo Conroy and Jared Madere. While visiting the space, the trio also ducked into the laundromat a few doors down, where the gallerists also did their weekly wash. Immediately the format activated the lingering play on tongues/tails, the symbolic status of the home washer-dryer, as well as a photograph by Dora Maar, Untitled (Shell hand) (1934). Installed in unused machines, the tails were both hokey and wondrous, haphazard and deliberately staged — their dual function to transform the appliances into portals but also call attention to the space surrounding them. In many ways, this is a contemporary re-harnessing of the surrealist ideal of the “marvelous.” As Hal Foster puts it in Compulsive Beauty (MIT, 1993), this notion is pledged to “the re-enchantment of a disenchanted world, of a capitalist society made ruthlessly rational. [It] also suggests the ambiguity of this project.”

This ambiguity is inherent to the laundromat itself, which is underscored by the intervention: it is ostensibly a democratic space — open to all, but overdetermined by class and race. After all, the American middle-class dream of home ownership already comes as a package deal with a washer and dryer; to have to go without and venture into the outside already says a lot. Further still, this space is also the theater for the clashing forces of gentrification (who’s doing their wash, when, and why?) as they come into contact with the specific history of the Arlington Heights neighborhood in Los Angeles.

What was perhaps not expected was the way in which these objects, deployed into the world, came to exceed the bounds of the original gesture, taking on a life of their own — fueled by specific interactions, circulation in social media, and coverage by the local news. “Even Drew Barrymore posed about it,” recalls Erlanger with a laugh. Indeed, detached from their original site, the tails become free-floating signifiers — not a meme, but an image placeholder where different meanings can be projected. In a way, they provide a litmus test for different ways of connecting to an audience while maintaining no control over the image — but then again, think of the primary ways art is consumed at any given art fair. Click, point, selfie. For some this is a fatalistic endpoint, the evaporation of the art object and its integrity. But for Erlanger it represents different possibilities between cracks and fissures, unseen endpoints that, she readily admits, cannot be planned.