Originally published in Flash Art International no. 284 May-June 2012

Looking at society today, the fundamental question of whether human nature is good or bad seems to be answered. It is not just that the news is full of aggression, violence and conflict; that has always been the case. It is more that there are hardly any signs of faithfulness, authenticity, honesty or idealism anymore. Politicians do not decide according to what is best for society in general, but according to personal benefit. Managers of companies cheat and lie, offering rhetoric without substantial content. There have never been so many forums, meetings and summits, but instead of providing free discourse and a focus on solutions, they seem to serve their own structures: there is more talking in the world than ever before, but at the same time, less is being said.

Today we are confronted with a professionalized world; for every detail there are a number of specialists who claim great expertise. The problem is that decision makers are not necessarily those who are best qualified in a given field, but rather those who are best at understanding the dynamics of decision making. Instead of creative entrepreneurs with a vision, we are now at the mercy of bureaucrats.

From a behavioral point of view, the formalized communications of the professional world do not end with working hours. Most social encounters have developed their own formal protocols; social life has become formalized to such a degree that even seemingly random violent interactions follow a procedure. More shocking than the absence of reason in hooliganism, for example, is that such profound human feelings as hate and anger follow specific protocols of clothing, language and actions. It’s like the inversion of scripted reality: reality is not re-enacted for TV programs, but staged for real life. Social interactions are not so much defined by individual human needs anymore, but seem to be exclusively structured by a variety of cultural codes, expectations and forms. So where is the human being?

Contemporary art has always been a mirror of society, and indeed the conditio humana has been reflected in numerous works, especially since the ’90s. It does not come as a surprise, however, that the prevalent picture of mankind in contemporary art is rather negative. Besides a focus on popular culture, superstars or exotic forms of life all over the world, the human being in works of art mostly appears as exploited, alienated, neurotic, unfree and unhappy.

Fortunately, contemporary art has never been satisfied with the status quo and its representation; it looks for alternatives and values beyond. In line with one of the most substantial and old traditions of visual art, there are works that still reveal surprising perspectives. The existence of real human beauty is one such surprise. It is a surprise because either we have almost unlearned the ability to see beauty not defined by success, looks, ability, power and wealth, or because we no longer trust values like happiness, honesty and faithfulness.

Irina Botea’s videos mostly use defined structures — not in order to dominate the characters in her work, but to allow them to manifest themselves. Botea very often refers to modes of re-enactment and role-play; for example, in MeNoMe (2005 and 2010) she wrote a dialogue consisting only of the words “No,” “Me” and “You.” The verbal structure of the script is so narrowly defined that it does not allow much room for interpretation by the amateur actors; but for this very reason their gestures become more important, and we are made especially aware of the fun they are having during the performance. Another work, Ladybug (2007), has a similarly minimalist setting. An eight- or nine-year-old girl is shown dancing. The scene was obviously filmed without preparation, but even without being given instructions by Botea, the little girl lasciviously swinging her hips still follows a kind of script: a script given by Shakira, MTV and popular youth culture. Yet the girl has so much fun that the video can hardly be seen as a critique of mass media manipulation, but rather as an optimistic statement — that sometimes even copying a role determined by a commercial system can result in something profoundly authentic and beautiful.

The beauty of people in Botea’s work is crucial. Even in a video like Before a National Anthem (2009) with its strong socio-political background, she manages to show people as human beings and not as protagonists for the artist’s message. Botea asked several Romanian composers to write a new national anthem and then filmed the rehearsals with a choir. Certainly the work is a strong statement about the difficulties that southeastern European countries face in defining a new national identity after the downfall of communism. But at the same time it seems much more important to focus on the choir members’ mixture of professional concentration and individual joy. Thus the real value of national identity is revealed as something that cannot be squeezed into an anthem. It can only derive from a natural, mutual understanding within a group of people.

Phil Collins analyzes these topics in one of his best-known works: They Shoot Horses (2004) is a seven-hour disco dance marathon staged by the artist with nine Palestinians in Ramallah. Western pop music from the last three decades is played, and the young people are captured in a single camera take as they dance or stand around or sometimes slump to the floor. As in Botea’s work, the setting is not coincidental; the interruptions by power failures, technical problems and calls to prayer from a nearby mosque reveal a few very precise and problematic aspects of the situation. But again, it is not so much the conceptual decisions by the artist that make the artwork, but much more the people who perform in it. They become autonomous, emancipated from the artwork’s frame; they become the artwork themselves.

Over the last few years Turkish artist Köken Ergun has investigated various community rituals in different parts of the world, and in doing so has found another kind of beauty. This is particularly interesting given that rituals can be understood as a very early type of formalized communication: subjects temporarily give up their own individuality and perform according to collective rules. For Wedding (2006-2008), Ergun filmed more than fifty different weddings over several months in the same area of Berlin. Backed by uplifting Turkish folk music, the video celebrates the exuberant joy of the wedding parties, but at the same time it shows bizarre details. For example, a tally is kept of the monetary gifts made to newlyweds, evoking for European audience more the atmosphere of a bingo hall than the most special day in one’s life. But even if a specific audience may find this system of gift exchange rather unusual, it is still evident that the wedding ritual is nothing to fear. It is not against integration into German society; it is about people having fun.

Shot from a participant’s perspective, Ergun’s Wedding is not a conventional documentary. This opens up a crucial point: rituals may consist of systemic structures that need to be obeyed, but at the same time they offer the experience of sharing something with other people; they offer participation. Acting as a collective serves a basic human need, and the problem of collective action in Western society is not so much that we have to give up our individuality from nine to five, but that we think we do not get anything back. Western societies have eliminated the wholesome concept of the individual in favor of a selection of roles to choose from and to perform; we represent, pose, pretend or impress rather than “be.” What makes the people in Ergun’s video so beautiful is that, apart from playing their role at a social event, every human being is also important as the person he or she actually is: a friend, a relative, a fellow believer.

Ergun’s most recent work, Ashura (2011), develops this approach further. He filmed the Ashura ritual of the Caferi group, a Shiite minority in the outskirts of Istanbul. Every year on the day of Ashura they commemorate Imam Hussein, a grandson of Prophet Mohammed, by putting on a march through the neighborhood and a play about Hussein’s murder in the battle of Karbala. In the first part of the video, Ergun shows grim looking men who beat their chests and scan unknown verses in a garage and then in the street. He then goes on to the rehearsals for the play. The script is first recorded by professional actors in a studio, after which the dubbed-over performance is acted out on stage by ordinary members of the community. Because the actors are not real actors but bakers or carpenters in the neighborhood, and because they all make their costumes themselves, the result is sometimes funny but also very touching. The video ends with a scene showing the men crying together. Whereas Western media tend to show the Ashura ritual only as a gory theater performance, Ergun’s work is more about the people performing it. The result is not that we better understand the ritual, but that we can appreciate the people’s performance as something authentic and sincere. There is no element of threat or danger in the Shiite performance, which raises an interesting point: to not understand something intellectually does not necessarily mean that one must feel threatened by it.

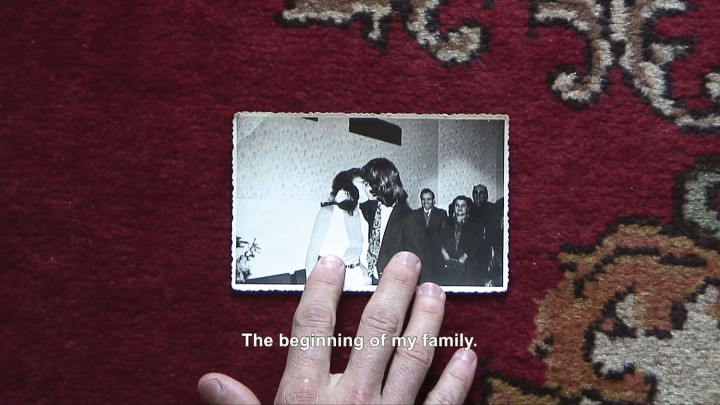

Ergun all but integrates into a community before he feels comfortable filming its members. But also in Botea’s and Collins’ work it is obvious that the artists do not so much care about their own message or the final form of the work, but instead enjoy the interaction, letting this define the final artwork. But the reverse also works: the authentic narrative and behavior of an individual can also be an excellent strategy for commenting on difficult socio-political issues. Nicolae Mircea’s film Romanian Kiosk Company (2010) recapitulates Romania’s history from the Second World War until now based on his parents’ kiosk business. The impact of national history is not demonstrated in the usual context of politics and economics, but within the very small circle of Mircea’s family. It is the narrator’s private point of view that manages to make national history not only understandable and human, but at the same time engaging.

This also points to the fact that in contemporary art there are few complex topics that can be reflected accurately by artists. The individual approach here offers a way to reference certain topics without being trapped within the inadequacy of aesthetic discourse. In Electric Blue (2010) Adrian Paci unfolds the story of a man who in order to feed his family started to copy porn films to VHS cassettes in the ’90s, until he discovered his son watching them. He decided to delete the cassettes by recording over them with war scenes from the news, but in the very end discovered that a few porn scenes still popped up between war reports. It does not matter if the story is made up; what matters is that an intimate and funny narrative can comment on very delicate topics: war and pornography as extreme forms of power.

Perhaps the most impressive work that reveals the beauty of human beings and interactions but at the same time provides a socio-political relevance is Ferhat Özgür’s Metamorphosis Chat (2009). Özgür filmed his mother, a very traditional Turkish woman who always wears a headscarf, together with her best friend, a modern, elegant and secular woman. All they do is change their clothes, but the point is how they do it; not only do they not have any problem with getting undressed in front of the camera, but they giggle and have fun, making the issue of the headscarf irrelevant. Just being human may not solve organizational, intellectual and social problems; yet we tend to overlook that it can offer new perspectives, sometimes revealing that a presumed problem does not even exist.