From Flash Art International No. 189 July–August–September 1996

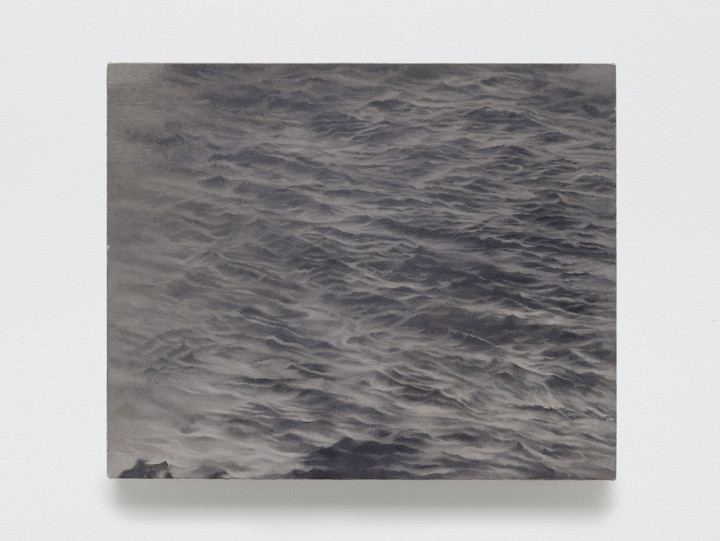

Vija Celmins (b. 1938; lives in New York) was born in Latvia but grew up in the Midwestern United States. She learned about art from a generation bred in the Great Depression and who believed that art was something crafted with the hand and soul and as timeless and enduring as sky and stone. Celmins was a generation younger than Jasper Johns and a world apart from then-unknown Gerhard Richter, but, like Richter, she found a way to use the photograph as a nugget of reality that she transforms into the flatness of paint. In the early 1960s she migrated to California, where she painted everyday objects and made others, such as a human-size tortoiseshell comb. Then she started painting oceans, galaxies and desert floors — small in scale but vast in intensity — all of which are thresholds of human migration. She quit painting for ten years and made graphite drawings of those same deserts, oceans, night skies, using the “mark” as a guide to clone an integrated surface. In 1977 she began a series called “To Fix the Image in Memory,” in which she had eleven stones cast in bronze and then painted them in acrylic to look like the real stones. They’re not identical, but it’s hard to tell the real stones from the handmade ones. Then she began to paint again, which she does slowly, incrementally, obeying the processes she’d begun long ago of recalibrating physical reality to fit flat dimensions. Celmins denies symbolism, sentiment and idea, and she does not “picture” reality, for her works are hybrids of imagination and reality processed through paint. Yet in her working of surfaces we, as viewers, can find Pythagoras’s music of the spheres and an imaginary future, as well as unchanged and unchangeable time.

Vija Celmins: I had a thing for painting as a kid. I went through five years of art school in Indiana. It was very traditional and uninspiring, except for the other students. The biggest influence that I had were the abstract painters from the 1950s, because they wanted to do something impossible — like make a painting that would move you through the paint itself. They were involved with touch. But in the late ’50s we were all involved with strokes and gestures. In my twenties I did my first objects — which I always think of as goofy. Like the comb, they don’t fit the space they’re put in, somehow they fall out. Sometimes the perspective is off, like there is no painting space, only a backdrop. Sometimes the objects seem pushed out, and appear without progression. Later, after I moved to California, I painted everything in my studio — my radio, refrigerator, the heater and so on. Most of those works are gone. Destroyed. Lost. Some of the students from UCLA have them. Then I began making paintings from clippings that I’d collected. I did single images, like the airplanes. I was thinking that I wasn’t going to have to compose. Then I stopped painting and took up drawing. The material and the dark and the light of the pencil lead took over. I fell in love with the lead. That relationship lasted until the early 1980s.

Jeff Rian: Abstract Expressionists showed the painting process, while your work has a surface perfection more like picture-oriented artist Malcolm Morley’s or James Rosenquist’s: the smallest glitch tarnishes them. Did you somehow combine the two styles?

VC: Unlike the Photorealists, whose paintings I found really dead and flat, I wanted to bring images back to life by putting them into a real space that you had to confront. I adjusted the image so that it fit on the surface without popping out, so that it was totally flat and natural, and so that all of my strokes were given over just to the image. In Malibu, in maybe late 1968, I had one of those light-bulb thoughts. I used to walk my dog on the beach and take pictures of the ocean — everybody was working from photographs back then, but not so much in LA. It occurred to me that if I were to make an image that was solid looking but still trying to pull you into a picture, there would be a problem. But if I had an image that interlocked with the picture plane, then the problem would be solved. That’s when the ocean images evolved. I made a break, and other things opened up: to make it work two-dimensionally, you have to abstract it.

JR: Your paintings are flat, yet they conjure deep perspectives, timelessness, acoustic space. Do you think about such things?

VC: You know, when you’re in the studio, you can’t consciously make that. You make a totally different thing. If somebody makes a rocket, someone else can make it from a set of plans, but I can’t tell you how to make a painting and get the same effect. I can tell you formulas, and about flatness, and about compression, but I can’t tell you how to make the same painting. It’s created in little, unnamable nuances. I wrestle with making the image fit in a small, flat surface. I guess there’s a sort of timelessness. The image and the making of the image evolved together. They’re traditional, but consciously done.

JR: Still, your subjects are primary elements — sky, earth, water, home. Traditionally, sky is father, air, remoteness, distance; Earth is mother, home, creativity and fertility; water is elixir, generative fluid — the Muses were water nymphs from whose springs the poets were said to drink. Now we go on vacations to re-create ourselves by looking at water, at sand, at sky, which takes you outside yourself. Also, the elements are timeless in that they register philosophical associations as well as physical sensations.

VC: But my work is in no way symbolic. It’s about making, and about how an image can be flat and illusionary, and how those two are brought together. That’s the part where the art is. Skill helps in finding the balance. It’s difficult to work with imagery and not have it be totally hokey and stupid. Nowadays assemblage has become a way to deal with subject matter. What I do is build an image in paint. Maybe that gives you the timeless quality, because they are made over and over again. There’s a certain amount of skill in holding the image so that it seems correct and full. But they are also very restrained and flat so that you get a sense of time that is captured and held. That’s where the paintings come from. But the part that’s interesting is the restraint, the total acceptance of flatness; that you’re composing something from the three-dimensional world in an abstract space. You sense all those things. It’s not idea art. Nor am I like Agnes Martin, who talks about Buddhism and the spirit. That’s not my inspiration. I never thought you went to an art museum to say to yourself, “What a great idea!” You go to a science museum for that, or read a book. You look at art to have an experience with things that compress time.

JR: Can you describe the scale of your paintings?

VC: One of the reasons that I make small paintings is that I want you to grasp limits. Okay, the ocean is vast and amazing, but the painting has limits: it’s a controlled object; you can see what it’s made of when you get close to it. At maybe ten feet it goes flat. It lives through your interacting with it.

JR: So how do you see the viewer’s role?

VC: I’d like viewers to forget that there’s an ocean outside of the work. I’d like them to get involved with the work and see that it was made, confined, intriguing, moving, lively and, hopefully, that it’s been made from scratch. Then you’re really there. The viewer has to participate in the work by looking at it and seeing the changes that have occurred on the surface. Sometimes the audience doesn’t see clearly enough to complete it. El Greco, Cézanne, Van Gogh were missed. I come from Latvia, and we Latvians, like Russians, have a very different idea about painting — so different you’d have to write a book to explain it. It’s hard to know on what level my art is understood. Right now a lot of younger people are able to see my work in a way that wasn’t possible some time ago.

JR: I’m reminded of Ananda Coomaraswamy saying (I’m paraphrasing here) that art is in the artist and is the knowledge by which things are made. He wrote about traditional art, in which artists used formulaic images and what we call iconography to create images. They can improvise, but only within the formula. They develop skill over a period of time; but it becomes unconscious out of habit. And their works evolve through a kind of calibration process in which adjustments are through conscious and unconscious processes, meaning that you use your skill and way of knowing — whatever that is — to bring art to life.

VC: Just in making things with a hand and an eye, things happen that your mind couldn’t think of. I want to maintain that duality between depth and flatness, keeping the two very close together, so that at one point it looks like nothing, like Formica or like dust and dirt on plastic, then when you look again you see that it was made, that a canvas has been filled up. Everything is close to the surface, but when you step back, it’s a galaxy, deep space. A lot of art now is manufactured or made of found objects that are combined together. You have to complete it in your mind. I think there’s something profound about working in material that is weird or stranger than words, and is about some other place which is a little more mysterious.

JR: What about the connection with photography? Richter has said that he wanted to paint a photograph as a kind of object in itself.

VC: I’m not really into photography or photography-based art. For me a photograph was subject matter apart from myself. Richter is much more conceptual than I am. He has very little tension in his work. He’s also diverse and prolific. But he doesn’t seem to build his paintings brick by brick. He has an idea, then he creates a “look.” Sometimes the look is really masterful. I torture the surface more. I don’t like people to read my paintings like photographs that were put in a developer — the developer was a human being. They may look correct, but they’re really misshapen and abstracted. In photographs I like subjects — China before the war, places I’ve never been…

JR: Richter also seems to use images to elicit memories and associations, which was also something that Pop artists did using commercial images.

JR: Richter also seems to use images to elicit memories and associations, which was also something that Pop artists did using commercial images.

VC: I never really took on the commercial aspects of painting and its use of images, as did Warhol or Lichtenstein or even Richter, who sometimes has a reproduction-like quality in his work. I flounder with how to make the image. The one thing I got from Pop art was that people had the feeling they could do anything. For me it was the possibility to paint anything. I painted my stuff, my clippings. But imagery comes and goes. It’s not what painting is really about.

JR: Walter Friedlander described classical art as being focused on something outside you rather than inside you, and Bernard Berenson described classical art as frontal and timeless and without narrative or an effusion of emotion. Berenson also found a similar classicism in Piero della Francesca and Cézanne.

VC: Both are balanced: Piero was a magician. His perspective was so critical. Even after you take one apart, something remains that you can’t explain. I don’t think painting can hold wild emotionalism.

JR: What other artists do you look at?

VC: Lots of artists. I like Ryman because he’s so sweet. The way he lays out the paint; it’s so tender. I used to love Morandi —which you can see in my early work. He had a hushed inwardness and a kind of withdrawal in his objects.

JR: Your work evokes the silence of a Morandi, although it’s somehow much more enveloping, because your echoes run deeper than his works, which are like reliefs or human relics. Yours easily could pre- or postdate us.

VC: Morandi’s paintings are actually quite strange. They all seem to fight for the same space. A lot of artists appreciate Morandi, but is there a Morandi room in the Museum of Modern Art? They push Picasso and Matisse. I understand that, but sometimes Picasso looks sort of quaint. In the Picasso Museum in Paris you see that quaintness. But his art was very connected to his life. When I first started to talk about my work, I would say that I was from Latvia and people would make obvious connections. You don’t see Ryman’s life story in his paintings.

JR: To me artists condense things — life, nature, events. You also deal with exteriority in a very interior way.

VC: I like art and I like nature — I like New York, too, it’s very interior. It’s a place where you think, where you apply yourself. My longest involvement with nature was working on those stone pieces. I really looked at them. I took five years, on and off, to work on them. Painting them was an experience in looking. The person looking at them now also gets to look hard at them. You’re almost forced to. Looking was the only thing that mattered. Sometimes I think my work gets too cerebral, too distilled and refined. I’m going to try to pull away from that. In fact, what we’re doing is a little silly, isn’t it? Everything that we’ve talked about is absent until you come face to face with it. A lot of people tend to like the work I did in my late twenties — the objects — because it’s more accessible. A lot of articles featured that work. It’s hard for me to look at it. I only like the very last things I did — the galaxies, oceans, deserts — and I don’t even like those. I just want to be in my studio.