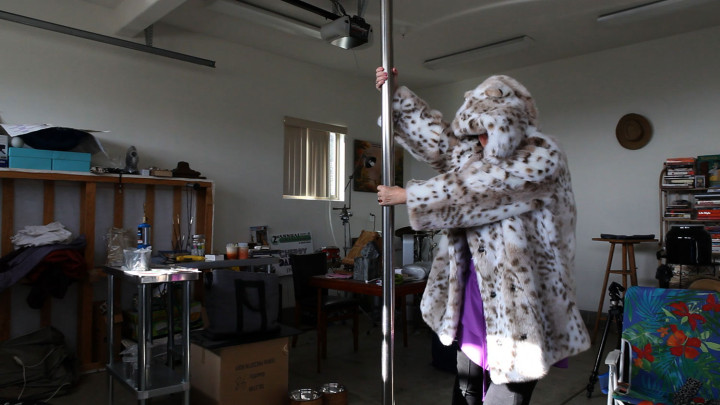

“I don’t have any time machine, but I have an archive.” The words are spoken by Lydia van Vogt in one of the opening scenes in Amboy, the 2015 film by writer Mark von Schlegell and artist Frances Scholz. Beginning as a docu-fiction about the real-world widow of science-fiction author A.E. van Vogt, the film ends up hunting after clues regarding the life of an enigmatic, fictional artist named Amboy. In the fascinating and all-too-brief portrait of van Vogt, we catch snippets of anecdotes from the Golden Age of sci-fi, watch her thumb through the contents of rows of filing cabinets, pull books off the shelves, and enumerate names: Ray Bradbury, Jerry Pournelle, Larry Niven, Harlan Ellison, Forrest Ackerman, L. Ron Hubbard.

Of course, any archive is like a time machine, but a sci-fi archive is Janus-faced. With its simultaneous forward-looking imagination and backward-looking textual immersion, the archive time machine seems like a particularly apt image for von Schlegell’s System Series, the ongoing sci-fi sequence he began a decade ago. To date, three novels —Venusia (2005), Mercury Station (2008) and Sun Dogz (2015) — comprise the series, which proposes a delirious vision of the near future — teeming with time travel, artificial intelligence and strange species — grounded in a fascination with the history and tropes of the genre and a particular interest in textuality.

Von Schlegell began his career as an art critic and essayist, though his turn to sci-fi has hardly been a goodbye to the art world. He keeps his foot in the door through his frequent collaborations with Scholz and the occasional catalogue essay. In 2011 the Contemporary Art Museum of Bordeaux mounted a large group exhibition, “Dystopia,” based around a story of his, framing it as “a show written by Mark von Schlegell.” But if he has one foot here, that leaves only one more, and von Schlegell has not exactly been embraced by the mainstream of science fiction — though he is not without his admirers in that camp either. Hyperactive, psychedelic and self-conscious, his works have an avowedly underground quality, as if written to exist in precisely these margins. That his publisher is Semiotext(e) might tell you something about his books. They are probably too weird to be accepted into either the ranks of the genre’s literary tier or the mass of geeky pulps.

This is not to say that that his approach to sci-fi entails tongue-in-cheek tourism. A reverence for the annals of the genre is palpable, often made explicit in allusions and in-jokes. While he most closely recalls the new-wave ranks of Samuel Delany, Ursula K. Le Guin and, above all, Philip K. Dick, von Schlegell draws on antecedents back through the age of the pulps and to the scientific romances of the nineteenth century. As Fredric Jameson has pointed out, intertextuality marks one of the key features of science fiction: “Few literary genres have so brazenly affirmed themselves as argument and counterargument.” What distinguishes von Schlegell’s work is the breadth of his embrace of this discursive history, the contents of which he then throws into a blender.

The System Series is set comparatively close at hand, in and around our neighboring planets during the twenty-second and twenty-third centuries, in the sometimes-isolated communities and colonies living in the wake of earth’s collapse. Narratively, these works are unruly and digressive. The books all run short of three hundred pages — slender by genre standards. It’s a torrent of plot, character and especially information. The question of what’s happening at any given moment — itself not always easily answered — tends to be less significant than the wide-angled view of the fictional world and its emergent meanings. Which is not to say that the latter is always precisely graspable either. The connotative, like the denotative, is fitfully expansive — a kaleidoscopic thematics of authority and submission, mind and cognition, techno-optimism and pessimism, utopia and dystopia, gender and sexuality, and the nature of time, truth and fiction, to name really but a few. Eagerly taking up the cliché that sci-fi is really just about the ideas as well the one that says genre fiction is plot-driven, von Schlegell jacks up these truisms with hyperactive doses of Deleuzian schizophilia and rhizomatic logic.

It should be evident that these works obviate easy summary, but I’ll see what I can do. Venusia, set furthest in the future, in 2250, centers on an isolated colony on Venus, where it takes 243 “Terran days” for the planet to rotate around the sun. “To counteract the unfortunate situation, the colony’s robot factories manufactured Terran Standard Time by blowing a hole in the eternal cloud cover every twelve Terran hours. The regularity established an illusion very like time.” The action takes place over the course of the last few Terran days before the colony will sink into a hundred some days of darkness. A kind of benevolent dictatorship, the colony exists under the control of Princeps Jorx Crittendon, aided by a culture industry impresario, Larry Held. The largely illiterate populace appears generally content with a bread and circus of narcotic flowers — consumed at a compulsory twice-daily collective intake, known as “the feed” — and a televisual technology called, simply, “V” — reality V being the most popular.

A group of four people, brought together by chance meetings and unified by their sudden abstention from flowers — a refusal that results in intense hallucinations, particularly of giant lizards — end up fighting to prevent a further power grab by Crittendon. They are a celebrity V hostess; an officer in the secret police; a neuroscop, a psychiatrist of sorts whose helmet allows her to explore the minds of her patients; and a dealer in cheap antiques, who has in his collection — though he doesn’t know from where it came — a book dealing with the history of Venusia, which he struggles to read and attempts to sell, setting in motion the events of the novel. There is a good deal of paranoia, confusion and amnesia — both personal and historical. Characters jump in and out of each other’s minds, and take long visionary journeys through a trans-dimensional interconnected consciousness called the neuroscape. Reality is never very certain, and the characters busy themselves with trying to establish the lines of the real. Crittendon himself (spoiler alert!) turns out to be “an extraordinary machine” whose ambition is “to make himself real. But for the Princeps to be real, history itself would have to be proven un-written. Venusia, a dream.”

Mercury Station is a time-travel story that gets into a little sci-fi-fantasy genre crossing. Eddie Ryan sits in a juvenile detention center on Mercury in 2150. Born in a laboratory, “a second-time creature, one outside of natural selection,” Ryan had been raised by the Black Rose Army, a post-Earth group of radical Irish nationalists, before his imprisonment for “terrorist” activities. His jailer points out the futility of Ryan’s political commitments: “The Official Irish Republican Army laid down its arms in the twentieth century. The Provisional Irish Republican Army quit in the first decade of the twenty-first. At that point your Irish politicos died out to be replaced by capitalists of the sort who contributed to the extinction of the biosphere as much as any Englishman.” That jailer, an artificial intelligence, MERKUR qompURE, engages in long, sometimes witty, exchanges with Ryan, interrogating the prisoner about his past, which he has difficulty remembering. The authority that had established the prison has since collapsed; MERKUR qompURE is a remnant that keeps the thing going in the absence of any legitimate jurisdiction. The prisoners have no hope of ever getting out. Ryan, now thirty-seven, should have been set free at twenty-one.

He discovers a mysterious book under his pillow. Penned in 1345, the work is the product of both a girl who was to be put to death as a witch and a time traveler from the future known as Peter the Peregrine. Ryan does end up escaping, through the help of Count Reginald Simwe Skaw, a celebrity collector and dealer in antiquities, who has found evidence of the existence of time travelers, or chrononauts. We trail the elliptical story of Peter the Peregrine and plunge into discourses on the nature of time. Ryan’s consciousness is projected back into the mind of the condemned girl to help write the book that he will later discover under his pillow. Despite any seeming similarity to the clever narrative tricks familiar from fictional depictions of time travel, Mercury Station proposes, in place of an image of time as awesome but manipulable, a sense of historical time as confounding and cruel.

The most recent of the three of books, Sundogz, takes place on the moons of Uranus in 2145 and is by far the most difficult to summarize. It opens in the Oan Bubble, an idyllic, polyamorous, sealed-off oceanic society of dolphins and mermaids. Deary Devarnhardt, a mermaid, has gone on an aquatic ramble, a swimabout, accompanied by an Oan Guard named Doll, who is himself some kind of post-human entity with long tendrils. Deary, an avid reader of pulps and sci-fi, discovers a previously unknown book by the widely adored author — and her favorite — A.E. Winnegutt. As they reach the surface of the Bubble, Doll and Deary are kidnapped by Captain Wawagawa, “a writer, publisher, and freelance creative,” piloting the ship Good Fortune to moon Miranda, where a science-fiction conference is to be held.

Numerous characters and intrigues converge on Miranda, a female-dominated community. Among the arrivals is Will Darling, a publisher about to release a new volume of Winnegutt — the same text that Deary found — which he himself wrote in collaboration with the deceased author’s dog transmogrified into an AI. He’s concerned that the feminists of Miranda will take issue with the killing off of the book’s main character, Deirdre, who, we learn, is somehow Deary herself. There is a plot to overthrow the radical feminist society, a mentally projected performance of Pericles, a threat to reality itself posed by the AI, and much more.

In all of this, the titular system is, of course, our solar system, though we glimpse the outlines of quite a few others as well: socio-political, ecological, technological, perceptual. Such is the privilege of speculative fiction — the freedom to sketch the contours and details of a different physics or political economy or consciousness. Von Schlegell clearly delights in system building, elaborating the rules that govern the order of things in these often-secluded pockets of life. Yet his worlds tend toward instability, entropy, even a kind of lawlessness, undermining the very systematicity that he simultaneously draws up. The rules seem to disintegrate just as they come into focus. In part this volatility comes out of the sheer number of ingredients thrown into the stew. In Venusia, for example, we have AIs, time travel, dystopian political allegory, history and creation myths, and Dickian paranoia and blurring realities. The dreamlike neuroscape, connecting the minds of the colony’s inhabitants, may allow for time travel as well as the machinations of the authoritarian state. We get glimpses of the colony’s history, figures out of the past making contact with the present — in and out of the neuroscape. At one point it is suggested that the hallucinated lizards, which may actually be real, are, in fact, dinosaurs, pulling something like a return of the repressed. Meanwhile, side-by-side with the humans lives a society of willful, sentient, highly intelligent plants, capable of controlling human minds and possibly history itself. No one of these things becomes the driver of the narrative or focal point, turning point or big reveal, nor could you say that they cleverly or intricately fit together. Instead they coexist in an overlapping, mutually attenuating, oddly nonhierarchical patchwork, a kind of rhizome of potentialities. In this, von Schlegell’s protean, sometimes opaque works seem to present the tortuous entangling of systems, a vision of systems as fundamentally unmanageable or incomprehensible — an epistemic reflection of our era in which everything is systematized and systematizable, though no one really knows how any of it works.

Within von Schlegell’s morass of systems, there is one of particular interest, the one named as such. System Space, or sometimes just the System, is a possibly federated interplanetary political entity overseen by the Global Authority. In typical fashion, the precise nature of these things is only lightly sketched, but we are given hints that the GA came into being after a liberatory period of early settlement and space travel, while it continues to grapple with the demands of Free Spacers. We also catch wind of the fact that System Space is already in decline, perhaps collapsed by the twenty-third century of Venusia. In place of an extensive treatment of the political, von Schlegell offers a vision of history in which the utopian possibilities born of earth’s destruction in turn fizzle out in familiar patterns of coercion and civilizational decline. Crisis is always already at hand, a vision of history as watched over by Walter Benjamin’s famous angel: “Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe that keeps piling ruin upon ruin and hurls it in front of his feet.”

A thread of optimism runs through as well, and we might characterize it as the familiar humanist view of the capacity of literature to enlighten. As we’ve seen in each of the novels, books not only play a central narrative function but also have transformative power. Texts rewrite reality: Ryan becomes Peregrine, Deary Deirdre. Even certain colonies are the creation of authors, written into existence. But it is not literature full stop, but specifically science fiction that is endowed with metamorphic potential. This speaks to a moral and political imperative, when there is no outside of capitalism, to imagine the future; but it also brings us back to the simpler pleasures of fandom and to van Vogt. His 1946 novel Slan, which concerns an eponymous breed of highly intelligent, super-evolved humans, gave rise to the slogan “Fans are slans.” Readers of sci-fi are smarter. Maybe they can save us from ourselves.