Even though Dresden and Leipzig are not so far apart geographically, the quality of painting emerging from these two East German cities is clearly different at the moment. Dresden painters like Thoralf Knobloch, Eberhard Havekost, Thomas Scheibitz or Frank Nitsche, for example, are convincing above all because of their ingenious analysis of the pictorial options at the beginning of the new millennium — rather than languishing in kitschy world-weariness painted in the manner of the old masters, like the Leipzig school. The difference is apparent in Thoralf Knobloch’s work, even in his choice of subjects, which are as clever as they are unobtrusive: a football goal, constantly recurring dustbins, jetsam and river landscapes, roofs, traffic signs and a car park are some of the things that appear in his pictures, carefully recording his everyday life in East Germany. This formerly real everyday socialist realm trundles along completely unspectacularly, trivially and apparently peacefully. It is never idyllically sentimental or expressively suffering, as it is with the oh-so-deeply-moved Leipzig painters. The fact is that rash and subjective psychologizing is alien to the Dresden artist; instead he places his own perception on the aesthetic test bench. Thoralf Knobloch himself mentions “exploring possible actions in the creative system” in this context. Motifs — carefully selected details with nuances of color and form — are photographed first and are translated into paint. The varied brushwork and the well-calculated, seemingly two-dimensional division of space compel Knobloch to reflect on his own view of the world, his own visual acquisition of reality in artistic terms.

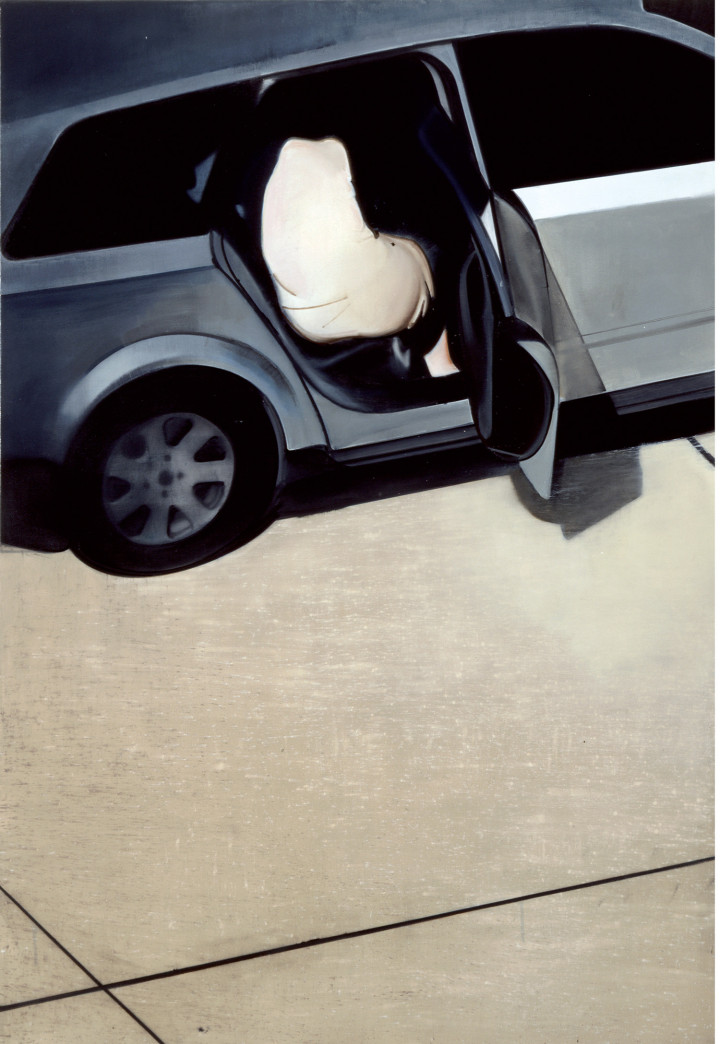

Like his friend and colleague Eberhard Havekost, Thoralf Knobloch photographs his intended subject matter. As a manic ‘hunter-gatherer,’ roughly in the manner of Walter Benjamin, he passes through his immediate environment — here he is different from Havekost in that anything exotic is alien to him — looking for possible motifs, and then captures the views he finds interesting on film. And so he deliberately uses two media for his aesthetic processing of reality: photography and painting. But these two media do not function in his art as rival competitors, in the way that art history once posited, but as accomplices, mutually complementing each other. An ultra-rapid, mechanical record made with the aid of an easily operated device undergoes a laborious, craftsman’s development with the aid of a paintbrush. Something allegedly objective is confronted with something as subjective as possible, suggesting a before, an after and an in between, or to quote the artist again, a “painting process as a challenge.” In addition, photography offers a prop for the memory, providing sensual data that are subsequently brought up to date by the painting. Something else is important in this two-media use: Knobloch’s painting is thus immune from getting involved in unduly historicist and antiquated realms of art, even if his motifs, like river landscapes, jetties, rooftop views or jetsam, or also his way of handling the phenomenon of light in a painterly fashion, are of course full of artistic allusions.

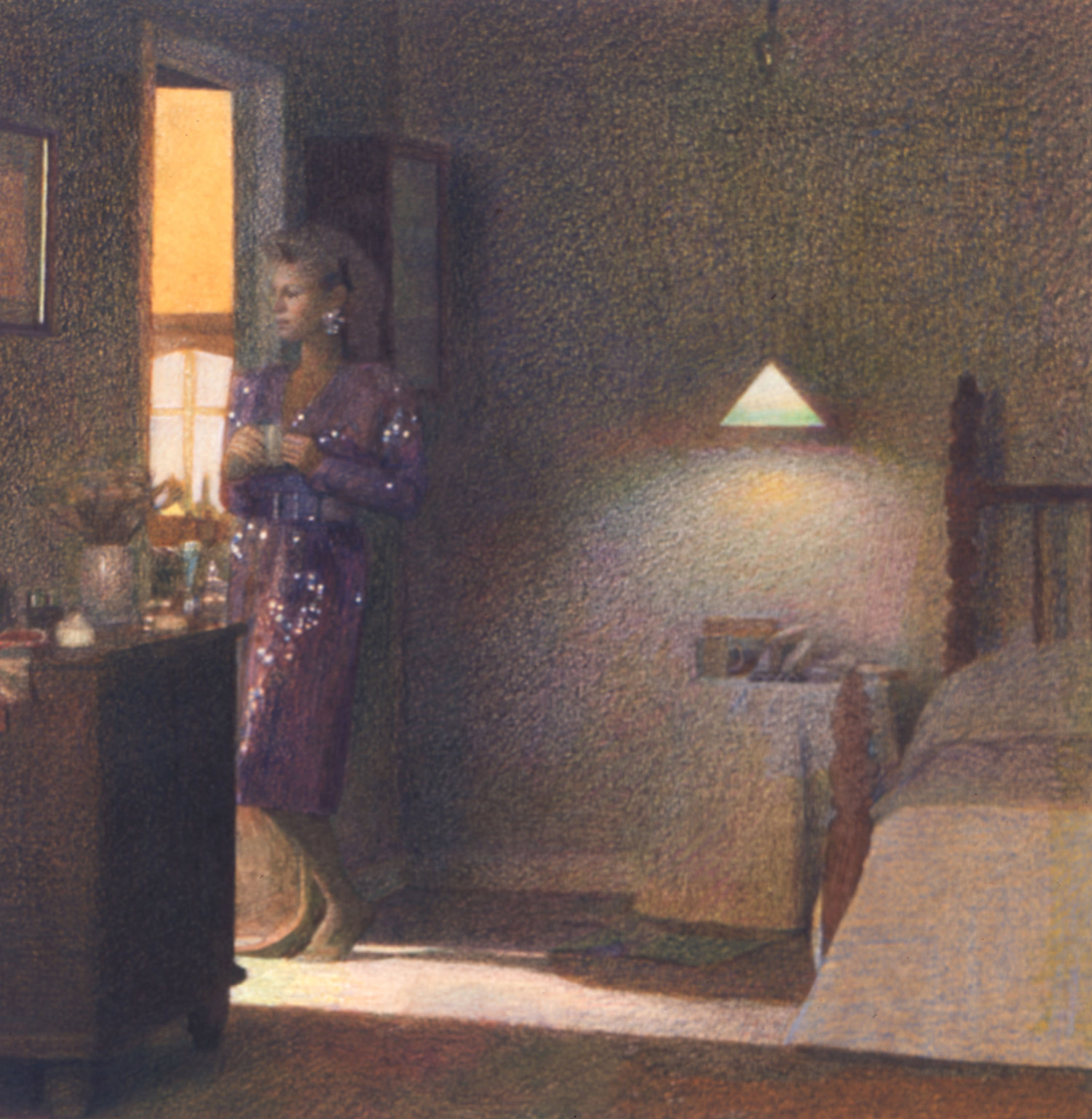

A striking quality of this painting is its quasi-objective ‘dryness,’ which often runs counter to the often yearning, sometimes dreamy character of his painterly motifs. Tor (Goal), 2004, is painted quite dispassionately, but actually shows every footballer’s dream; Strandgut (Jetsam), 2003, tells of wanderlust and distance; and Pieskower Wald (Pieskow Forest), 2003, reminds the viewer of earlier experiences of nature. But this tension between emotionally charged content and essentially austere form definitely has a method behind it in Knobloch’s case, as it is the way in which the artist succeeds in bringing alienation into the artistic game, something that is central to his postmodern experience of the world. If there is a thread running through this very diverse oeuvre it is probably that man is unduly cool in relation to his environment. This latent feeling of alienation is of course related above all to his own biography, as Thoralf Knobloch could not avoid being involved in the historical collapse of the Communist social system of the German Democratic Republic, which was crucially influential for him, and the subsequent adjustment to the quality of life under capitalism in West and East Germany, which is difficult and has still not worked out successfully. For this reason too his pictures show no signs of either luxury or brilliance, but instead a Blaue Baracke (Blue Hut), a discarded Sack (Bag), a constant Schutt (Rubble) and a Teddy lying on a dustbin. It is interesting to see how in the case of Teddy the ‘good old days’ of childhood and the by-no-means pleasing state of affairs in the present collide. The naïve, innocent paradise is contaminated: the ‘darker sides,’ aspects of everyday East German life that painters often suppress, become viable material for painting. This process is entirely ambivalent: on the one hand these ‘darker sides’ are shifted into the focus of art and thus laid open to discussion; on the other hand their reality as art is always weakened, or prettified in the worst cases.

Yet Thoralf Knobloch’s art is anything but resigned, or even cynical. The painterly translation of photograph into painting in fact successfully aestheticizes the most banal and trashy things, charging them with added sensual value, without betraying this everyday quality to false affirmative hopes. One strategy here is the tendency towards abstraction that enters his aesthetic master-plan in many of his pictures. The tattered beige Plane (Awning), 2004, hanging down from its light-blue pole is more like a piece of colorfield painting than a truly realistic picture. This triggers a “game with illusionism and an attempt to conquer it,” a game that prefers to reflect on art’s space rather than merely fill it up decoratively. A comparable inclination towards abstraction can also be seen starting to affect pictures like Elbblick (Elbe View), 2004, Pool, 2001, or Baumhaus (Tree House), 2002, for instance. In the last case it is only the title of the work that makes it into a representational painting. The painting Strandgut (Jetsam), 2003, however, tends towards poetic tachist abstraction, with representational reference and formal autonomy striking a skillful balance.

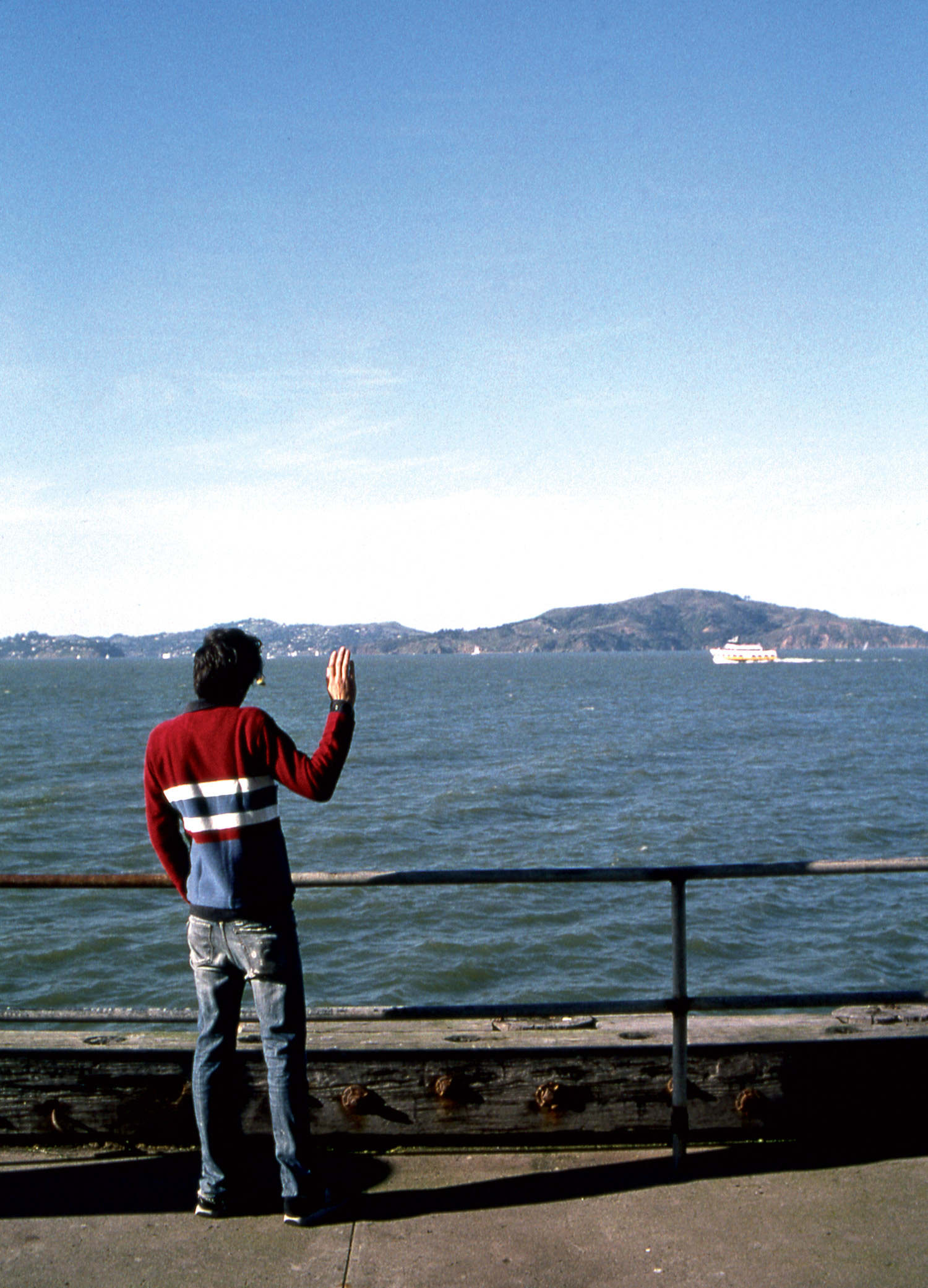

Elements of some sort of joie de vivre are more rare in Thoralf Knobloch’s art, though they do occur. Paintings of sporting scenes such as Boot, doppel (Boat, double), 2003, are the best examples of this, or of woodland swimming pools, as in Waldbad Klottzsche, 2001: children are playing in front of impressionistically dabbed-in trees, by water that seems in its turn to have been painted by David Hockney. Hockney’s influence is even clearer in Knobloch’s picture Springer (Diver), 2001, in which a youth is plunging head first into refreshing blue swimming-pool water. This transference of US-style Pop art to a representation of the East German provinces is an entirely skillful chess move by Thoralf Knobloch, as it enables him to link these two spheres of life that are actually so alien to each other. The link manages to question both spheres of life mutually, and also to poeticize them mutually: the provinces become too beautiful to be true, and Pop at last becomes romantic.