In 2022, I was invited by Frieze’s director, Christine Messineo, to curate a series of artists’ projects, installations, performances, and talks along the coastal west side in response to the fair’s move west to the Santa Monica Municipal Airport in February 2023. I took this opportunity to revisit some of my favorite texts on the City of Los Angeles at large, including Mike Davis’s City of Quartz (1990), Norman Klein’s The History of Forgetting (1997), Chris Kraus’s Video Green (2004), Peter Plagens’s The Ecology of Evil (1972), and Jean Stein’s West of Eden (2016). I was inspired by Klein’s “anti-tours” in which, as a professor at CalArts, he would take his students to vacant sites because Los Angeles tends to erase memory: “a movie studio, a whorehouse, whatever.” Klein explains that the buildings had been demolished because of LA’s penchant for self-erasure. Thom Andersen got it all wrong — LA doesn’t play itself; it forgets itself.

The project, titled “Against the Edge,” brought the work of five different artists to five historical and culturally significant sites along the coast of Los Angeles. Contrary to what one might expect, the projects did not exclusively feature Los Angeles artists, nor did the artists need to have a relationship with the site in question. Taking a cue from Jean Stein’s skill for recording oral history and joshing with its factual faultiness, I used these imago-sites as an opportunity to mix history, urban myth, anecdote, and personal memory to create a story of not only what’s gone but what’s left.

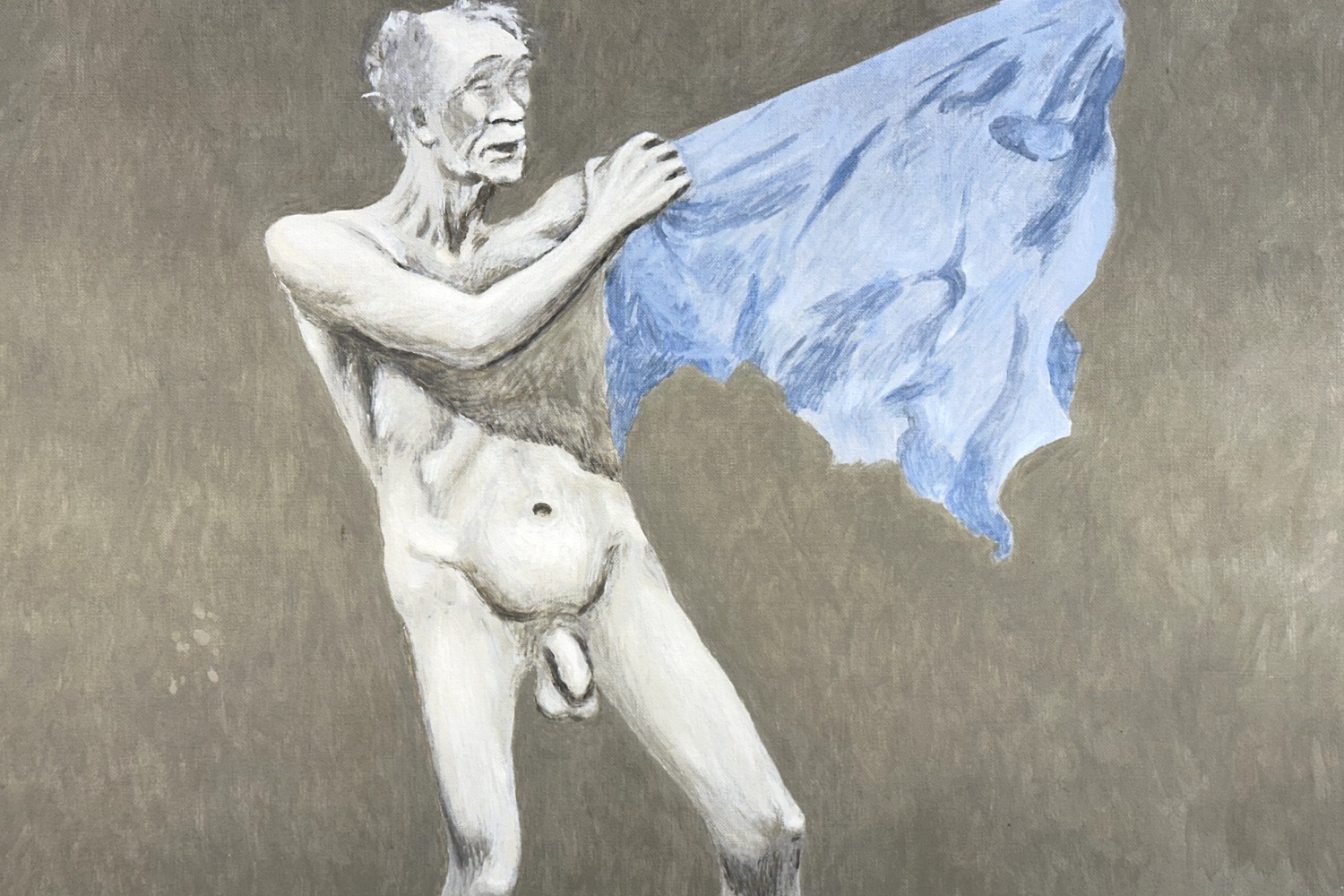

The projects included Heirloom (2022), an installation by Kelly Akashi at the home of exiled German writer Lion Feuchtwanger and his wife Marta, who arrived in Los Angeles and purchased the abandoned Villa Aurora in 1941, around the same time Akashi’s family was forcibly relocated from Los Angeles and incarcerated at Poston, Arizona, following Executive Order 9066, which ordered the mandatory deportation of Japanese Americans from all over the country into internment camps. The work of Moroccan-born French artist Nicola L., “Nous Voulons Entendre” (1975), was installed at the home of other exiled Germans, Nobel Prize-winning author Thomas Mann and his family. Nicola’s sensual functional sculptures, wall-sized paintings, and protest banners she called “Penetrables” rubbed against the hard and sterile lines of Mann’s modernist home, where he would compose his anti-war messages; “softness as resistance.”

Three video works (one of them being So To Speak, 2023) by Tony Cokes were installed throughout the library, foyer, and theater of Beyond Baroque, a nexus for artists and writers such as Wallace Berman, Jack Kerouac, Dennis Cooper, Simone Forti, Allen Ginsberg, Mike Kelley, and Patti Smith. Cokes’s video B4 & After the Studio Pt. 1 (2019), installed in the Beyond Baroque theater, drew uncanny similarities between the fate of Manhattan’s East Village and Soho and LA’s Venice Beach by examining the intertwined relationship between art, gentrification, and real estate speculation. For one night only, Jonathan Hepfer, creative director of Monday Evening Concerts (MEC), and a cast of notable figures from the worlds of visual art and music performed John Cage’s Speech (1955) at the Merry-Go-Round building at the Santa Monica Pier, which we called “Action 3.” This was in homage to Walter Hopps’s curatorial coup titled “Action” (1955), in which he wrapped the Santa Monica Pier’s carousel in a tarp and suspended paintings by Sonia Gechtoff, Craig Kauffman, Jay DeFeo, Richard Diebenkorn, and other California abstract artists while performing his own renditions of John Cage works.

At Del Vaz Projects, the nonprofit art organization I run out of my home in Santa Monica, we exhibited the work of late Los Angeles artist Julie Becker from her series “(W)hole” (1999), the first time the work was shown in Los Angeles since 2009. The installation consisted of a foam replica of a portion of the sidewalk of Sunset Blvd adjacent to the artist’s home and studio; photo and drawing studies of her imagined Tiki bar-cum-space shuttle; and a video in which she hoists a miniature bank building into a hole in her studio floor. Perhaps no other visual artist has been better able to capture the fragility and precarity of life in Los Angeles than Julie Becker.

Unlike Norman Klein’s “anti-tours,” the sites that hosted “Against the Edge” still exist and are very much active. Their stories haven’t necessarily been erased or forgotten; they just haven’t really been shared. That’s what provided me with the perfect theater to propose some new and imagined relationships between site and artist, history and fiction.

The project took its name from an interview between artists Fritz Haeg and Doug Aitken in Aitken’s book The Idea of the West (2011). In a collection of one thousand interviews, Aitken asked friends and colleagues, “What is your idea of the West?” Fritz responded: “To the American psyche: west equals movement, more space, resources, freedom… For those of us that do occupy this slim line along the Pacific Coast, we have a unique sense of limits. For everyone else, there’s a vague sense for everyone else: no matter how much of a mess we’re making here, there’s more that way. But for us living against the edge, it’s like. No, this is it. There’s nowhere else to go.”

A city against the edge, on the precipice, constantly forgetting, erasing, and reconstructing itself.

Perhaps the most dynamic, energized, and groundbreaking programming in Los Angeles today occurs in its alternative spaces, nonprofit organizations, and artist-led initiatives, which have understood how to navigate the fractured and inconstant nature of this city’s psyche and harness it to support artists, experimental practices, and nontraditional forms of experience, viewership, and community engagement. To do this, and to do it with care, requires us to be extremely resourceful, exist deeply in the present, and operate on an intensely intimate scale.

Over the last two decades, a robust number of these spaces, organizations, and initiatives have appeared and disappeared across Los Angeles. They have been responsible for the bold and vibrant “scene” that has caught the attention (once again) of the national and international, commercial, and institutional art communities. Admittedly, the recent loss of several spaces and projects over the past decade, such as the Chalet Hollywood, The Underground Museum, Paradise Garage, 356 Mission, and the Paramount Ranch art fair, has left an indelible mark on Los Angeles. But what remains is a vast and rigorous collection of spaces, organizations, and initiatives that have proven not only resilient to outside influences, market forces, and commercial trends but also diligent, agile, and exacting in their programming of visual art, literature, music, poetry, dance, and performance.

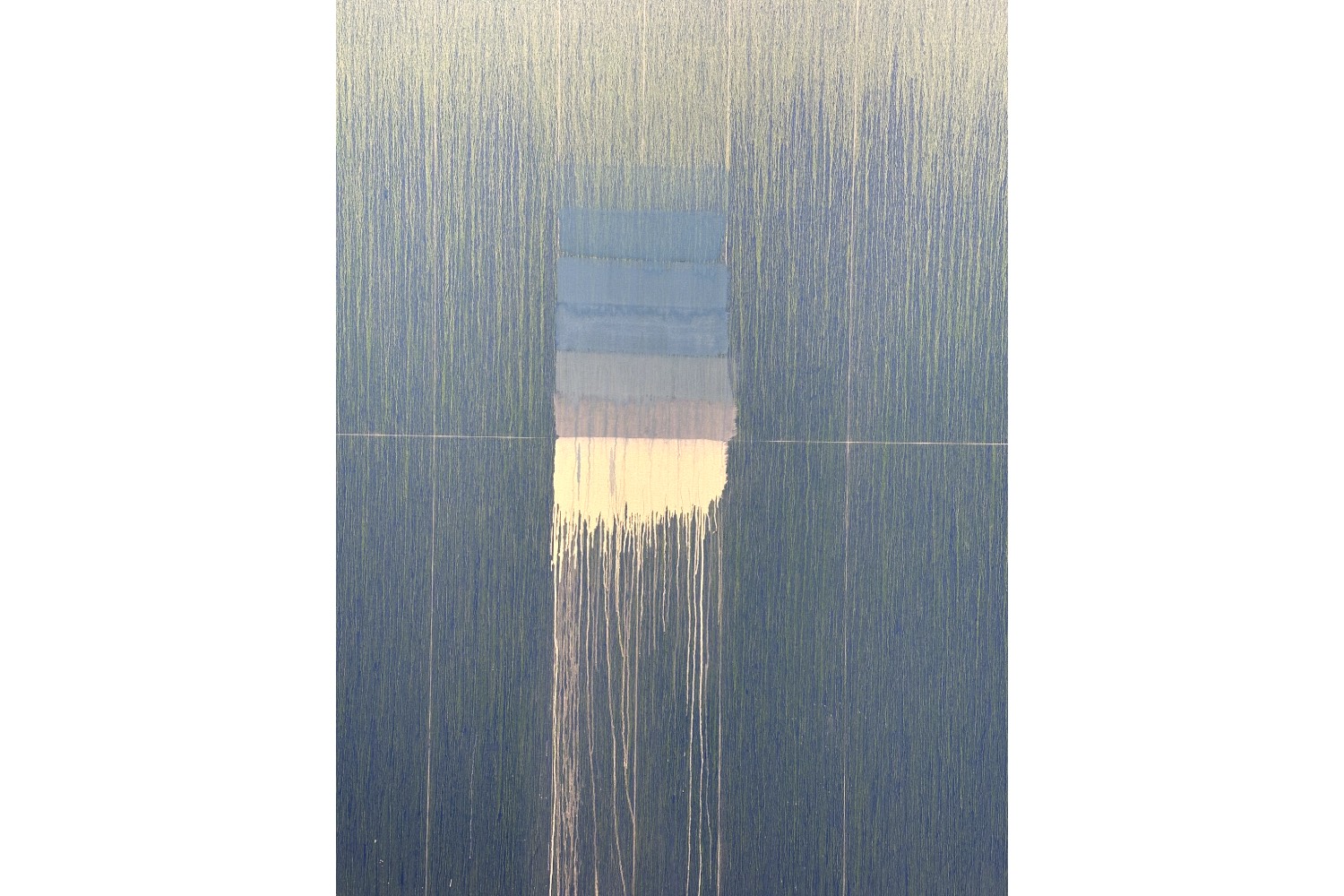

Long-established Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE), founded in 1978, has paved the way for a number of small- and medium-sized nonprofit organizations by fostering artists who innovate, explore, and take risks. This year, LAXART reopens as The Brick under the directorship of Hamza Walker, debuting their new space with the group exhibition Life On Earth: Art & Ecofeminism. Similarly, the Los Angeles Nomadic Division (LAND), founded in 2009, has been committed to presenting contemporary art in LA’s public sphere, producing museum-quality public exhibitions and programming across Los Angeles. Since becoming director in 2019, Laura Hyatt has focused on uplifting artists whose community-based practices foster healing and deepen a shared sense of belonging and connection. On the summer solstice, LAND will work with artist Lita Albuquerque to restage her work Malibu Line (1978), a forty-foot-long pigment work embedded into the ground that traces the artist’s matrilineal lineage from Tunisia to Los Angeles. It will take place on the site of Albuquerque’s home, which burned down during the Woolsey Fire in 2018.

Beyond visual art, organizations such as REDCAT, Monday Evening Concerts, and dublab continue their groundbreaking and dynamic programming in historical and contemporary dance, music, theater, sound, and multimedia performance. This August, REDCAT continues its yearly New Original Works (NOW) Festival, which has been premiering work by a vibrant community of performance artists for twenty-one years. One of dublab’s many ongoing initiatives includes LOOKOUT FM, a West Coast terrestrial radio home for the broadcast of transmission art: experimental audio composition, modern serials, data sonification, radio plays, multi-day compositions, and radio-centric performances. The station functions as an exhibition space where radio art is presented without regard to constraints of time, structure, or commercial consideration. For the upcoming thirtieth anniversary of the Villa Aurora’s artist-residency program, dublab has installed an antenna on the roof of the historic home, where live broadcasts of the resident artists’ works will be made on LOOKOUT FM throughout the year.

Founded in 1939 by Peter Yates and Frances Mullen on the roof of their Rudolf Schindler-designed Silverlake home, Monday Evening Concerts is the world’s longest-running series devoted to contemporary music. Originally envisioned as a forum for displaced European emigres such as Igor Stravinsky and Arnold Schoenberg during World War II, MEC has continued to make musical history for the last eight decades with early-career performances by such notables as Michael Tilson Thomas and Steve Reich. Since 2015, director Jonathan Hepfer has continued MEC’s legacy, pushing the organization into new frontiers with performances of David Hammons’s Global Fax Festival (2000), Wu Tsang’s Moby Dick (2022), and Julius Eastman’s [Masculine] / Femenine (1974). The upcoming season promises to be just as groundbreaking, with large-scale collaborations planned with Davóne Tines, Chaya Czernowin, Steven Schick, and Sarah Hennies, to name a few.

More than ever, and in spite of the caravan of large, “blue-chip” galleries arriving from the East Coast and overseas (and which I have conveniently left out of this feature), alternative modes of exhibition making and sharing abound throughout the city, largely run and managed by artists themselves who feel it’s necessary for the sake of their creativity. Following a collaboration with local nonprofit gallery JOAN for a project on David Hammons, artist David Horvitz will mount an exhibition of Arte Povera and Italian art from the 1970s in his garden-cum-project space later this year. Co-designed with landscape architect TERREMOTO, Horvitz’s garden is located next door to his studio and is “a kind of zen stone garden from the detritus of the city.” The garden was constructed using piles of concrete, rubble, and rebar from various sites around Los Angeles, including demolished buildings of LACMA, Ballona Creek, and the South Central Farm. It contains more than one hundred native plants and trees, including oaks, sycamores, manzanitas, wildflowers, roses, a juniper, and two plumerias from his grandmother’s house down the street.

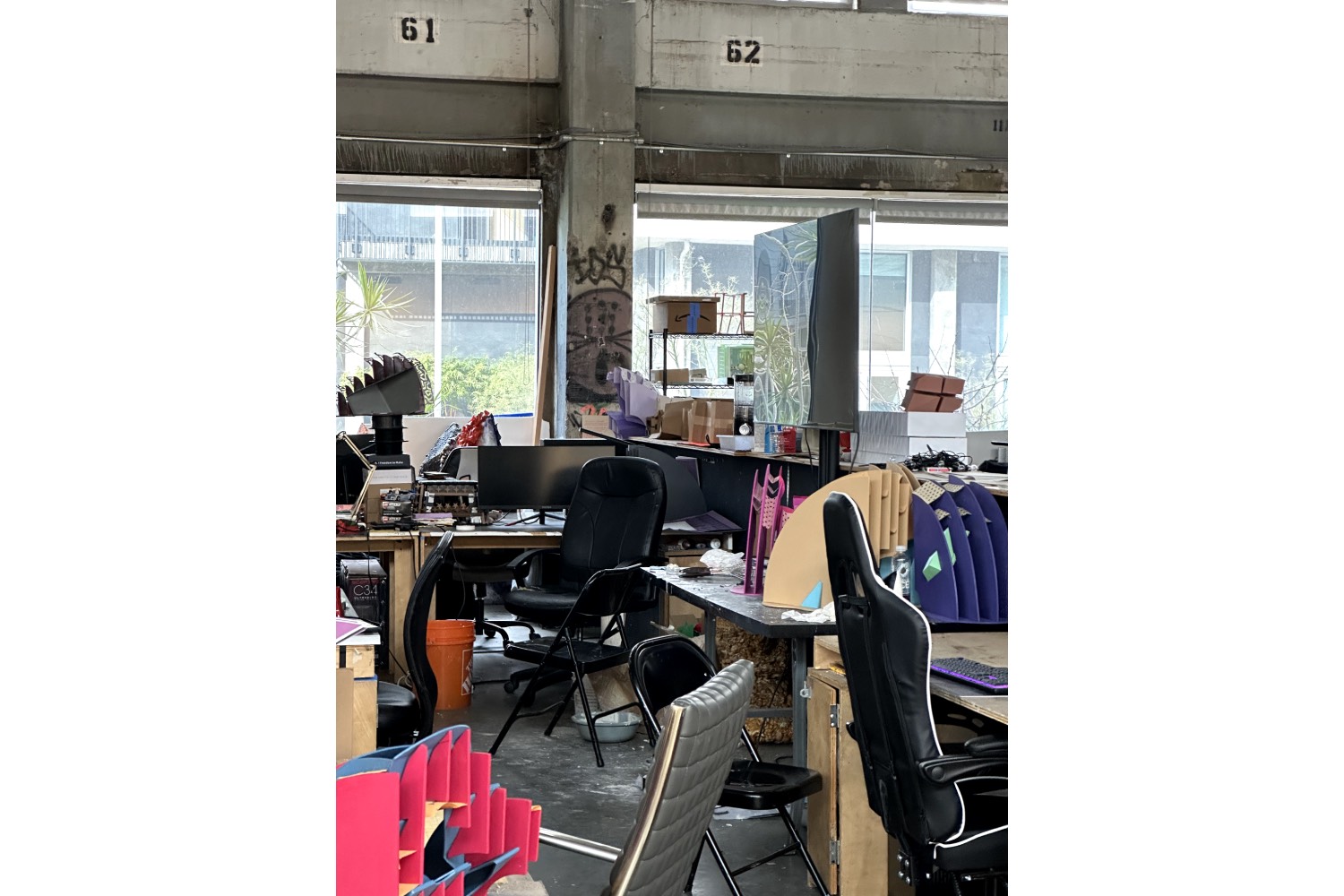

Next year, the Mountain School of Arts, founded by artists Piero Golia and Eric Wesley in 2005, will complete its second decade. The school operates nomadically, is free of charge, and has no permanent faculty. The curriculum, what some have described as a perpetual field trip, has brought students from all over the world into dialogue with many local and international cultural leaders, thinkers, and artists such as Tacita Dean, Dan Graham, Simone Forti, Pierre Huyghe, Richard Jackson, Paul McCarthy, Henry Taylor, and Jeff Wall, offering students a critical, ingrained, and comprehensive experience of the Los Angeles arts community. After years of exhibiting architectural prototypes at institutions nationwide, from the Hammer to The Met, Lauren Halsey will realize her much-anticipated monument in South Central Los Angeles. Presented by the aforementioned Los Angeles Nomadic Division, the semi-permanent structure will be activated with a mosaic of programming, from dance competitions to after-school tutoring for local young adults, through Halsey’s organization Summaeverythang Community Center.

In April and May, artists Dena Yago and Amy Yao carried out two projects at artist John Garcia’s The Bunker, a subterranean observation shelter dating from World War II located on public government land in the Santa Monica Mountains. Visitors to the shows had to meet Garcia at the trailhead in Malibu and hike about a mile to visit the bunker, where artists like Lucy Bull, Sam Lipp, and Tschabalala Self have previously installed their works over the last several years. Over in Beachwood Canyon, mysterious artist Nora Berman recently opened Hisssss, a gallery of small works encased in her three pet snakes’ tanks. Artist Joseph Geagan and his partner John Tuite, who started Gaylord Apartments in 2021 out of their high-rise Koreatown home, will open a show with Marie Angeletti this summer. The trio of artists Ramsey Alderson, Connor Camburn, and Emma Sims have recently opened P.E.O.P.L.E. with an exhibition by Pascal Siskin that is opening this summer.

At a time when it seems as though several commercial entities, international institutions, and media outlets have (once again) turned their attention to Los Angeles, as if it was some novel discovery, or even worse, a (fleeting) trend, it seems necessary to remind both the local and international art community of the way artwork works in this city. Most of the spaces, organizations, and initiatives mentioned above exist nomadically, whereas some don’t even occupy any physical space. Those with some semblance of permanence or physical presence often operate out of personal and domestic spaces like bedrooms, gardens, and garages. More often than not, we are addressing and redefining notions of space, land, and our environment, working with not only who’s already here (a lot of artists) but with what’s already here (a lot of a lot). This is absolutely obvious, yet utterly unattainable and unmanageable, even by the most deep-pocketed, well-staffed museums, galleries, and art fairs. Rather than operate within the visual-commodity culture dominated by extraction economics, these spaces and artists work genuinely and inventively to invest in themselves, each other, and the city.

There is no guidebook to survival here, but what we do know is to not do what they’re doing. Perhaps the way to survive, however, is to embrace and practice impermanence, which is, after all, the most “LA” quality of LA. Things end, people forget. Los Angeles doesn’t need to teach that to the “art world” — the “art world” is already really good at that.