I often say that if I was ever invited to curate an exhibition, I would choose the topic 1965, the year I was born. I have an innately strong connection to many artworks and respect for many of the artists working around this time that responded to technological and social change with research and innovation. Needless to say it was nice to be invited to review “The Responsive Eye,” a 1965 Museum of Modern Art exhibition that became known as the “height of the Op Art wave”1, as a way to investigate my imaginary show.

“The Responsive Eye” was curated by William C. Seitz, an early scholar of Abstract Expressionism who was progressive in his understanding of optical systems used by surrealists, impressionists, neo-impressionists, and also the Bauhaus. Although he planned for the exhibition to reflect this progression in art history, he realized the current or new practices warranted an exhibition of their own. Seitz selected 102 artists who were quite literally researching how the eye responds to experiences with foundational elements of art such as color, pattern and light in time and space. That these artists came from 19 countries and varying political and cultural beliefs (many of them from fields such as design, architecture, science, sociology and psychology) revealed an international curiosity and focus on the phenomenology of perception.

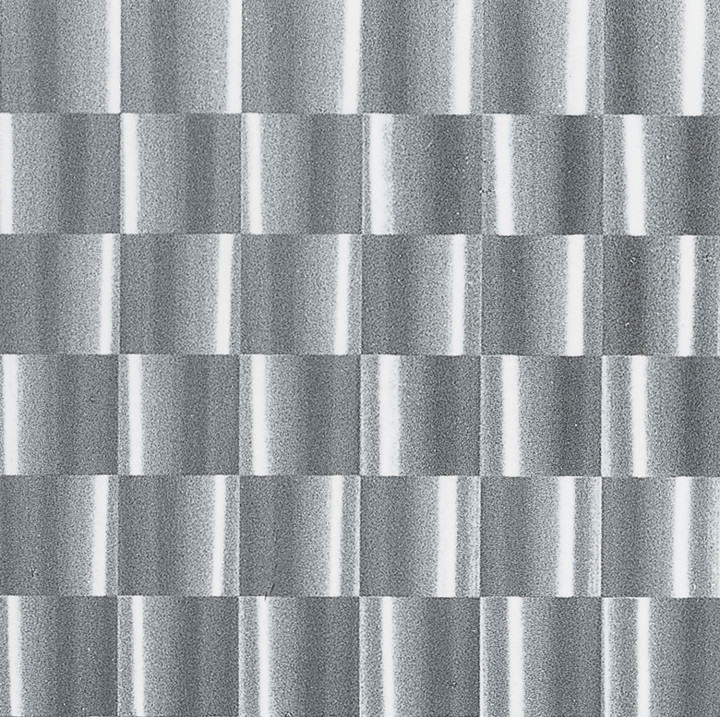

There were 123 works in the exhibition by well-known artists, such as Victor Vasarely, Josef Albers and Bridget Riley, as well as little-known collectives such as the Italian Gruppo N or the Spanish Equipo 57. The works provoked discussion that the process of seeing is not just mechanical: the nervous system is involved and thus changes our experiences, often disturbing expectations by offering alternative ways of seeing that had not yet been considered.

It is natural and historic that artists have questioned and heightened ways of seeing. And the theorizing of visual hallucinations goes back to the Berlin School of Gestalt psychology. Yet at the time (and still a debate today) the artworks and practices in “The Responsive Eye” were beyond the classical art historical referential system used by many critics, who raised concerns as to whether the art was art or rather an exploration of visual phenomenon that may be scientifically interesting but not related to art history. It was hard for critics to accept that many artists were leaving what I call ‘the frozen moment’ (my pseudonym for static, traditional production) and moving beyond the third dimension. In his catalogue essay, Seitz admits that the work goes “beyond what we call ‘art.’”2 Rather than trying to tell the audience what to see and how to understand it, Seitz validated Josef Albers’ guiding belief that “art is not object, but experience.” In Seitz’s words, “Ideological focus has moved from the outside world, passed through the work as object, and entered the incompletely explored region between the cornea and the brain.”3 The experiential or performative nature of the work meant that it could ultimately be understood without previous knowledge. The direct nature of the work did not overtly evoke conceptual analysis. For example, artist Getulio Alviani explains that he and his colleagues understood “light as a material; never as a metaphor of light.” The unambiguous titles of many works also demonstrate this directness, such as Instability Through Movement of the Spectator (1962-64) by Julio Le Park, member of Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel, Paris, or Black Moving Planes (1964) by Mon Levinson. Some titles completely demystify by being instructional such as François Morellet’s oil-on-canvas Screen Painting: 0°, 22°5, 45°, 67°5 (1958). On the one hand, the work has been categorized as being basically science-based, and even entertaining. On the other hand, it can be seen as a dedicated response to the situation at the time and, in that way, it was even a kind of socialist art in its reflection of the everyday. It seems there were perfect conditions to explore and share a type of art that engaged audiences in optical reactivity. The use of hallucinogenic drugs were accepted and widespread (LSD was made illegal in 1966). Television portrayed fascination with topics I love such as speed, space exploration and the future.

At the same time, there was also a growing resistance to war and a skepticism about power and media. As a simple visual connection, we can think about the 92% of American households that had a television the year the exhibition opened. That means that each day, nearly 200 million people were accustomed to seeing or manipulating the lines and grids on test cards in order to calibrate signals for a clear picture, inherently producing moiré effects in the process.

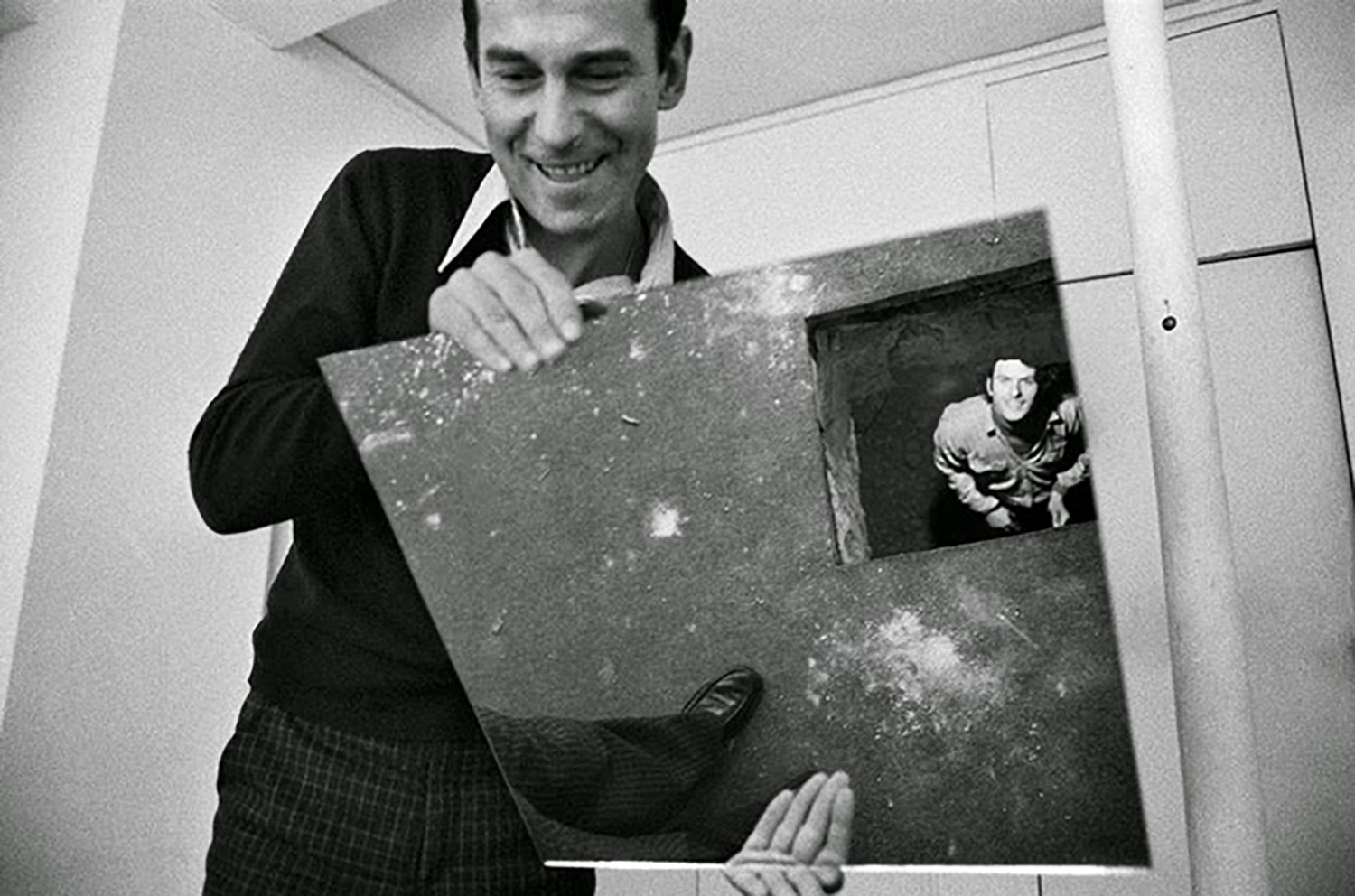

I watched a great episode of a television program called Eye on New York that covered “The Responsive Eye.”4 An earnest host reports on the popularity of the exhibition and shows engaged audiences moving through the galleries as if they are display-laboratories or optician’s quarters. A clear awareness of issues related to perception was occuring in the public and this gave the exhibition the character of spectacle. In the program, Seitz was featured and has a kind of premonition when he tells the host about the impact of superficial arts coverage: “And this, in a sense, does worry me, because it is really […] the absorption of modern art into modern life. And that’s something we all wanted, but it may change the character of the art […], too.”5

Although similar exhibitions had happened in Europe, it was the American debut that commercialized the artwork. The high-entertainment factor of the exhibition (which seemed out of Seitz’s control) was in contrast to the experience of the artist in the studio. Alviani reflected on the popularity of “The Responsive Eye” as a ‘tragedy’: “Our artistic license was robbed, sacked. Everyone utilized our images and misused and contorted our research, vulgarizing everything and debasing its significance, taking away the vital energy that each one of us reflected in our research.”6

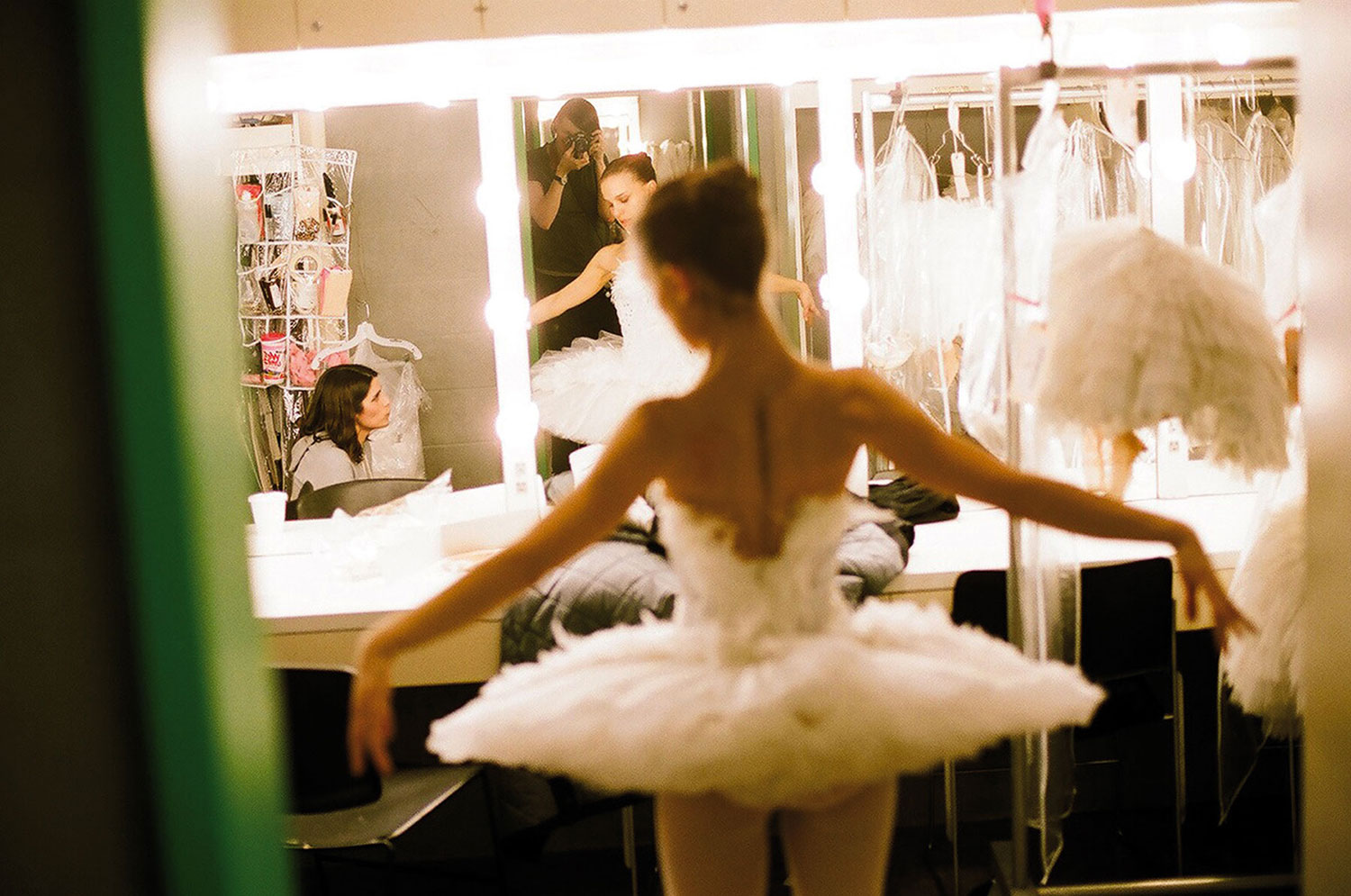

Looking back, it was the innovative and precise practices of these artists that expanded artistic freedom. They prepared a ground for artistic thought and practice that many artists now (including myself) use as if it had always been there. The idea to shift research, process and experimentation from the studio (the laboratory) into the display zones of exhibition areas perhaps shows what artists (and curators like Seitz) wished to overcome: the distance between production and presentation. This may have seemed like instability or chaos, or something that seemed antagonistic to the idea of a classical art history or the museum. Yet probably the idea behind all of it was to make more life visible and make art more touchable than ever.