Where the most ambiguous activities of the living are pursued, the inanimate may sometimes catch a reflection of their most secret motives: our cities are thus peopled with unrecognized sphinxes, which will not stop the musing passer-by and ask him mortal questions. But if in his wisdom he can guess them, then let him question them, and it will still be his own depths which, thanks to these faceless monsters, he will once again plumb.

— Louis Aragon, Le Paysan de Paris (1926)

Lined with loading docks and blunt one- and two-story buildings, Mirasol Street, south of Olympic Boulevard, is a row of small manufacturers — sweatshops and workshops for metal plating, LED lighting and women’s apparel. The facades are windowless; on a few you can see where someone, at some point, having deemed windows problematic, decided to block them out. I wouldn’t want to make too much of this scene — a world of activity (and of course exploitation, always exploitation) behind bricked-over windows; disjunction between inside and out; goods produced on an anonymous street in LA’s Boyle Heights dispersed into the ornamentation of the life of the city, of another city — but General Brite Plating Company seems to want me to. General Brite’s building is brick and stucco painted a pale earth tone, but its website is a small marvel, a hackneyed hymn to teeming urban life. The landing page swoons with time-lapse scenes of Los Angeles at night — the glittering skyscrapers of downtown, cars coursing through the 2nd Street Tunnel and circling the illuminated pylons at LAX, the pedestrian crowds along Hollywood Boulevard and the Santa Monica Promenade — set to languid strings and piano, which I’ve learned comes from the soundtrack to the TV show Lost. General Brite dreams a nocturnal Los Angeles, not that of film noir, but nevertheless framed by Hollywood. Glimmering and smooth, it’s a city where nothing is made; things are always already in motion.

On the other side of Mirasol from General Brite is a building that houses a couple dozen artist studios, and there Patrick Jackson (b. 1979, US) showed me some of the work for “Know Yer City,” the show he was preparing for the Wattis Institute in San Francisco. He gave me a tour of the model he’d made for the exhibition, the space divided twice by fabric partitions, spanning the width of the room, suspended from above and scrunched into accordion folds, while faces lined the two long walls of the gallery. Needless to say, viewing things in miniature, with a God’s-eye view, is not the same as being there, but as the show was built on the play of interiority and exteriority, the dollhouse version seemed oddly appropriate, like both prospectus and punch line. That titular directive to know your city has something of the impossible about it, hints that the city is, after all, unknowable. Because it’s your city — or yers — which means not only that its necessarily partial, but also that it’s the one carried around in your head, composed of appearances and countless memories, of threadbare or half-remembered myths, scenes from a million movies about this place. It is a dream object, at once shared and unsharable.

“Know Yer City” — it is also an anagram of New York City, which is not where the work was made nor where the artist lives, but it does feature in the show. Jackson created the partitions by stitching together theater backdrops depicting New York — a staging of the city as a composite image. The accordion folds, however, transform these painted canvases from backdrops into something closer to theater curtains. So we have a reversal — from setting to cover, back to front — that skips over the drama itself, elides substance and subject. In a more literal sense, the folds make the images on the backdrop-curtains illegible — at least they do in the model. I suspect the effect will be the same in real life.

Los Angeles appears in the other two components of the exhibition. There are a dozen five-by-seven-foot segments cut from used billboard vinyl, stretched like canvas, each with a human face looking straight ahead. Previously they all dotted the landscape of the Southland. They range in framing from head-and-shoulders to top-of-the-head-lopped-off close-up, and the group is racially diverse and split pretty evenly between men and women. Evidently, a few of these faces belong to B-list celebrities, but I couldn’t identify any of them, and neither could Jackson. Thus anonymized and decontextualized, they form a kind of serial photography of the face, not unlike that of several familiar genres — yearbook, headshot, mug shot — while testifying to the banality of diversity in advertising. Whatever distinct signification we see in, say, the stoic black male youth or the menacing bearded white guy, the overall effect of this typology of countenances is, more than anything, the surface and texture of urban experience.

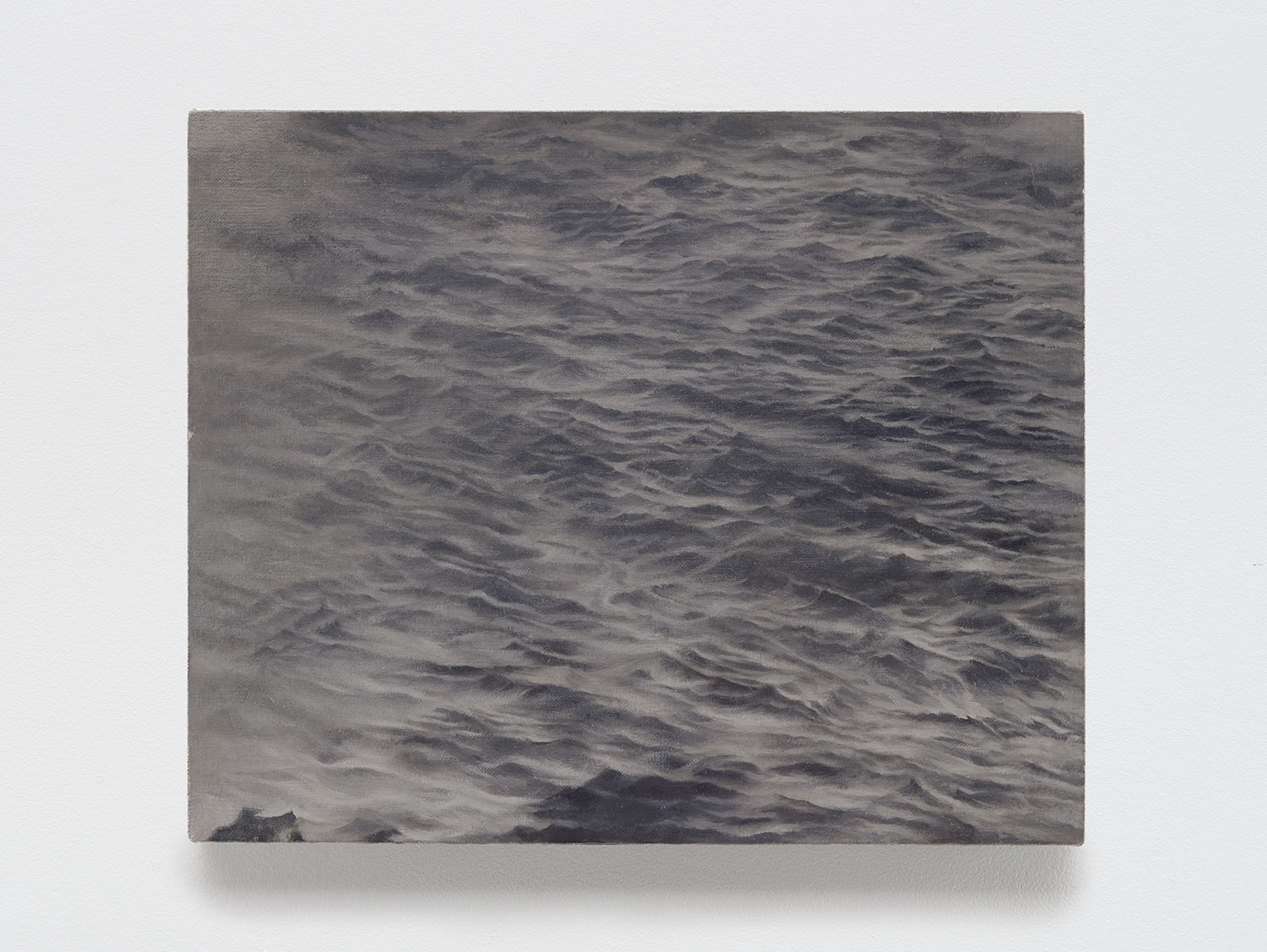

The final piece consists of a series of black-and-white photographs either documenting public sculpture in Los Angeles or else depicting Jackson himself, or some part of his body, inside of his apartment. Notwithstanding the affectless photoconceptual style of the pictures, they recall an earlier, wilder work that similarly contrasted the inside of an apartment with a totemic Los Angeles exterior — Julie Becker’s video Federal Building (2002) — a comparison that occurred to me, for obvious reasons, as I examined Jackson’s model of the Wattis. Over a soundtrack of Mexican rancheras, Becker cuts between shots of the hulking concrete California Federal building in Echo Park, which she could see from the window of her apartment, and a model of the building placed in various settings. Sometimes the model looks very much a model — as when it’s being lowered through a hole in floor — but other times it can be hard to tell whether the building you’re seeing is the big one or the little one, outside or in.

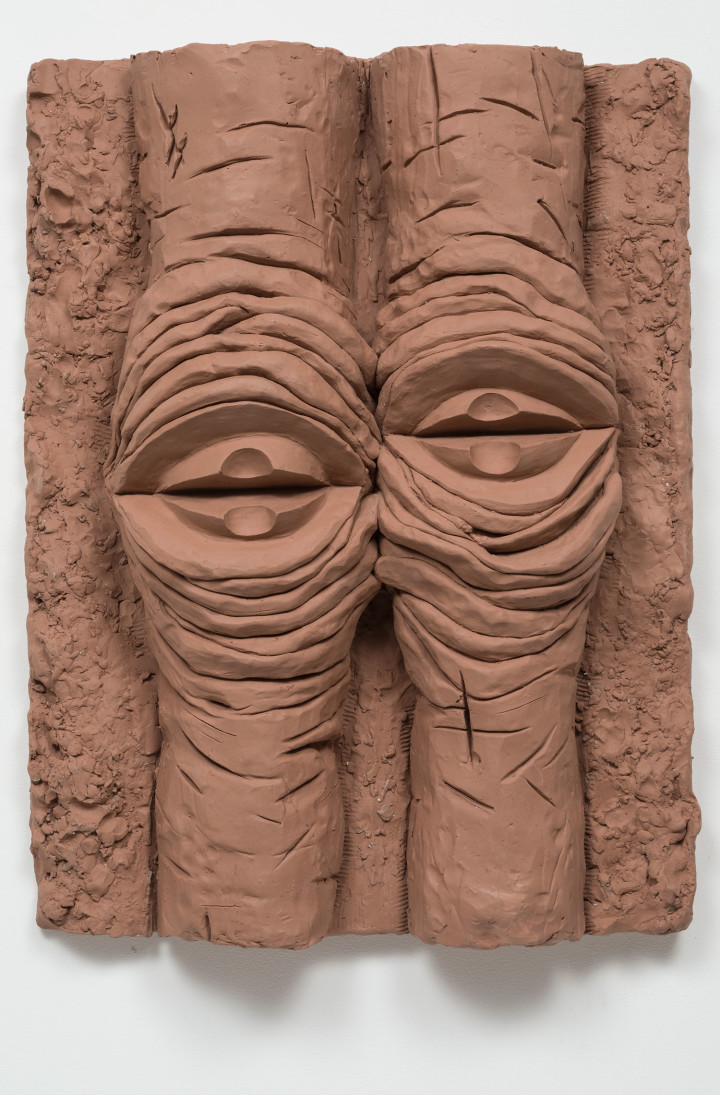

“Know Yer City” synthesizes a number of themes that Jackson has been working on over the past several years. Interior spaces have served for him as a metonym for the psyche, and this has sometimes translated into theatrical installations. He modeled his 2013 exhibition “The Third Floor” at Ghebaly Gallery, in Los Angeles, on Freud’s tripartite structure: An upstairs superego, containing only Black Statue (2013), a five-foot-tall resin sculpture of a boy with gaping, empty eye sockets; a ground-floor ego, sparse and carpeted white, featuring wall-mounted ceramic works, slightly abstracted curtains and windows; and a subterranean id space with dozens of ceramic vessels of cracked black glazing and colorful oversized mugs containing psychedelic epoxy goop and resin crystals.

Jackson shared with me a collection of journal entries, going back to 2011, which was to be made into a pamphlet that would be distributed at the Wattis show. Although he subsequently decided not to use these as part of the exhibition, they reveal a lot about his thinking. An entry from 2012 may well have been the kernel out of which “The Third Floor” grew. It discusses precisely the spatial mapping of an interior described above, though tellingly it does so under the rubric of “Notes on Public Sculpture”:

Public art is oppressive, it tells us how we should be. Think Washington, DC, other cemeteries, Rome. They’re like the superego:

“You ought to be like this.”

“You may not be like that.”

The Psycho house is layered like the mind: id, ego, superego / basement, main floor, top floor. Come to think of it, the mom in Psycho (the superego on the top floor) is a sculpture — dead, moved around and posed. And like other figurative work, it tells us what to do … or at least it tells Norman.

The slippage from moralizing public sculpture to the psychic totality of the interior is conditioned by movies. And movies are like cities, experienced at once as shared and individuated. Jackson’s 2011 exhibition “House of Double” sounds like a film noir you can’t remember whether you’ve seen. But never mind — you’ve already internalized the tropes. Mounted in an empty two-bedroom apartment in the building where he lived, the show played on the eerily familiar. Jackson staged groupings of domestic objects in the kitchen — a cane, a wrench, a sponge, a plate — and installed in the living room a set of sculptures made of dirt and epoxy atop vintage coffee tables, though it was hard to tell which part was uglier. The bedrooms each contained a nearly identical denim-clad bearded figure, barefoot, lying on the floor, eyes closed, fingers interlaced on the stomach. Titled Head Hands Feet (2011), each of those eponymous parts were made in a different manner, each evoking a distinct kind of dummy. The head (silicone and hair) reminds us of something from a special effects studio, the hands (silicone) sex toys, and the feet (epoxy) mannequins.

This kind of attention to material and texture characterizes much of Jackson’s work. His ceramics have strange and captivating surfaces. Often craggy and blistered and wildly colored, as if by a child’s crayons, they possess a cartoon violence and appeal simultaneously to the optic and haptic. Otherwise, they are dull and dark, like something unearthed from an archeological dig. At the same time, his practice as likely entails the arrangement or alteration of found objects, as with most of the work in “Know Yer City” or his Tchotchke Stacks, vertically climbing layers of knickknacks and figurines sandwiched between sheets of glass. Yet these two approaches to sculpture might not be so different in Jackson’s case. Both seem to depend on a common attitude toward objects, something like Freud’s famous line on the origin of adult sexuality in pre-oedipal relations, that “the finding of an object is in fact a refinding of it.” Even those things we make are always contained within, and containers of, memory — whether conscious or unconscious.

In Nadja, André Breton hunts the flea markets of Paris in search of strange and startling objects. The city itself for him is a great repository of defamiliarizing things, not least of which is Nadja herself. Jackson’s project might be seen then as a search for the refamiliarizing object. The uncanny too is a trope; experiences and memories are predicted in the movies. You already know yer city.