What are the stakes of insisting upon political hope, in all its felt potential for redeeming past injustices, when progressivism is under attack globally? This is the question taken up by “The Gatherers” at MoMA PS1, organized by Ruba Katrib and Sheldon Gooch, a sprawling yet precise group exhibition of fourteen international artists thinking through unmet promises of liberalism. “The Gatherers” does not offer a direct answer but rather attempts to provide some preliminary roadmaps to a latent future unhinged from violent forms of accumulation and consumption: not through revanchism, but by denaturalizing various kinds of fetishes that make such violence possible in the first place.

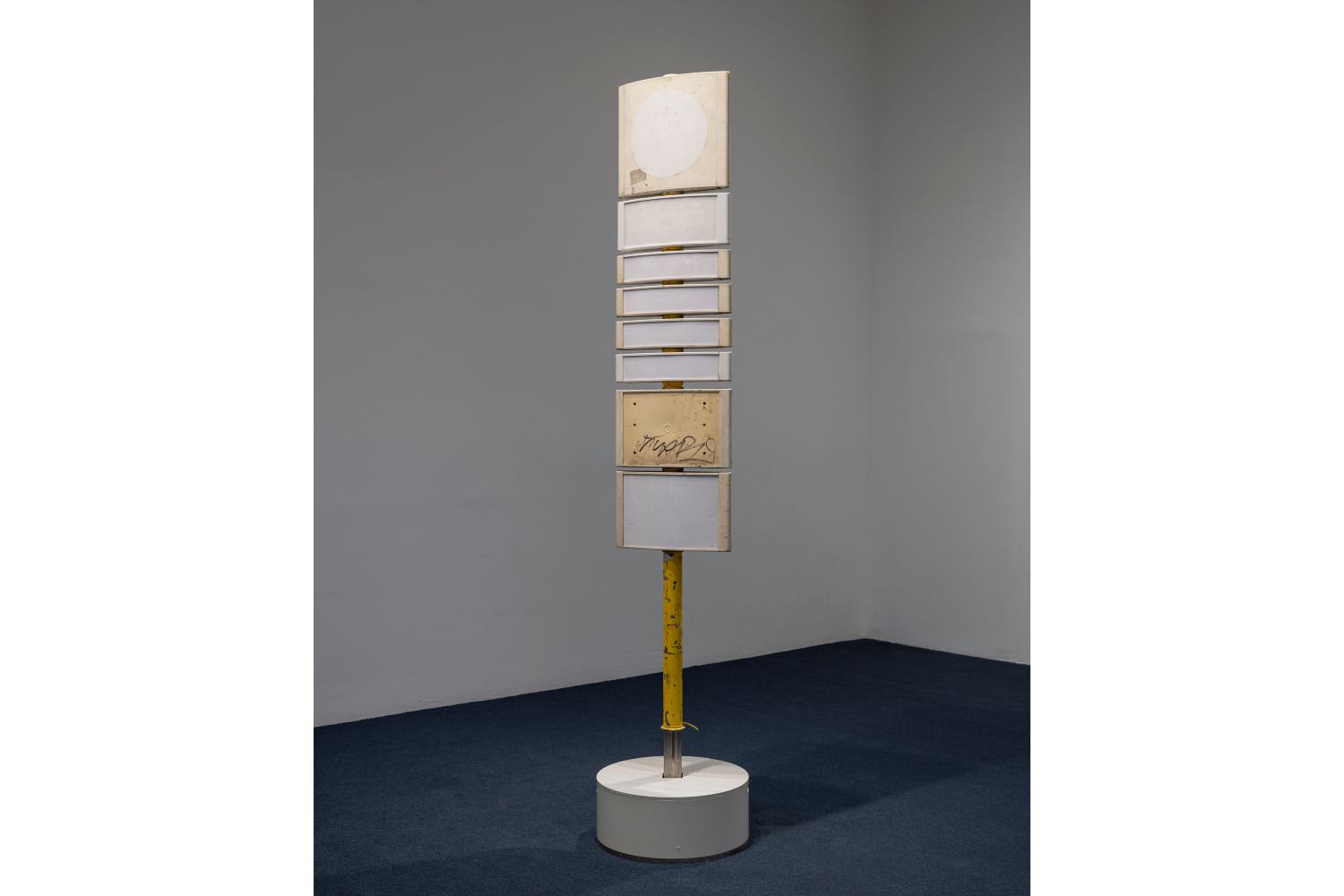

Ser Serpas’s sculptural installations made from urban detritus (all 2025) elegantly showcase her ability to borrow from chaos toward generative ends. Of the six works, find me and surrender cadence sweet trite maybe lose tinges of solitude and again acknowledge me, tube of brief cadavers made sadder still and it festers while it stances up in that tree most concisely demonstrate Serpas’s attunement to the theatricality of failure, in which accumulation does not necessarily result in meaning-making, but detours into impossible architectures, and short-circuits into apparatuses that know no distinction between interiority and exteriority. Serpas’s sculptures are neither artifices nor artifacts; intimately arranged and estranged by their editing, they turn the process of positioned collecting against itself. An ontology is implied here: the intensity of labor involved renders Serpas’s invisibly implicated body a surrogate and an accoutrement. And, if anything, Serpas tells us that our flesh can have these seductive encounters with abandoned objects: so much so that we might re-animate their potential with our own willed spirits.

The struggle over labor — who owns it and who gets to represent it — lends itself to cinematic narratives. Andro Eradze’s Flowering and Fading (2024) employs a slow-moving camera surveying a domestic space at night. Gravity ceases to function as a gust of wind (perhaps aftershocks from revolutionary storms that hijacked the angel of history’s motions?) marches in. Furniture levitates, as alive as the wilderness outside. Symbols of nature and culture similarly no longer oppose each other in Emilija Škarnulytė’s Burial (2022) and Zhou Tao’s The Axis of Big Data (2024). In the former, a meandering serpent—a symbol of enlightenment or degradation of innocence — on control pads in a disused nuclear station creates suspension, slithering under a trapped camera that jumps between simulations of half-decay and wide, distant views of extractive energy infrastructures yet never enters the inhabited world beyond uranium imaginaries. In the latter, unmotivated studies of a data center’s computational units are clinical and claustrophobic. Luckily, Zhou’s narrative expenditure concentrates on refreshing, serene documentations of nearby villagers farming and raising animals. Long before the data center’s arrival and its technological time, human time has shaped contested lands and will continue to do so; it is evident the artist knows well. Elsewhere, a rare moment of clarity is found in Karimah Ashadu’s Brown Goods (2020), which, with an anthropological brevity, exhibits how exchange between the metropole and the periphery is a multi-directional movement of divergent, sometimes conflicting, ends.

Phantoms — objects with only exchange value, haunted by lost use value, leaping into unrealized potentials and missed opportunities — form Tolia Astakhishvili’s immersive environment Wicked Plans (2025). Scattered architectural miniatures and models and exposed pipes and ducts suggest a construction site. Yet surrealist-influenced collages by Astakhishvili’s father and defaced pages from old magazines by the artist’s mother, sealed under plexiglass, unmistakably ground Wicked Plans in the dramatics of domesticity. Confusion between production and reproduction proliferates. On drywalls of various dimensions and scales layered upon each other irregularly, we see conspiratorial images of alternative lifestyles, family photos, snapshots of the artist’s social circle, drawings hinting at violent eroticism, documents sourced from unknown archives, confessional scribbles with no certain addressee acting out wish fulfillment, and residues of ghostly figures. All distinctions between historical disjuncture, linear time, séance, and exorcism are collapsed.

Astakhishvili toys with our illusory investments in time as well. Foreclosures of futures manifest horizontal movement without a horizon line. In dark days (2025), a chute leading to nowhere encloses viewers’ perceptive field, only permitting peeks of trinkets and hardware tools, which could possibly be ruins of a family from the distant past. In so many things I’d like to tell you (2025), made in collaboration with Dylan Peirce, a scanning machine deciphers a watch, numbered file folders, and an evolutionary chart in a near posthuman future with inconclusive findings — the machine’s output does not become legible through time, but bears traces of a past that threaten to displace its presentism.

Are forces and relations of production quasi-metaphysical or biological? “The Gatherers” gestures toward the social and its contained mutability. To this end, Geumhyung Jeong’s Removed Parts: Restored (2025) surgically and performatively lays bare robotics used as props in information dissemination. Each dissected part defies calculations of modulated interchangeability, resolutely insisting on its own difference. For Jeong, the production of subjectivity and its labor is ever-recursive, and recesses and slippages sometimes can be more paramount than the totality. Still, “The Gatherers” offers no lesson. Look toward Samuel Hindolo’s painting Galgenberg Hill (2024): the Palace of Justice in Brussels is stripped of its grandeur, resembling dented silhouettes, and justice is yet to be served in fallen empires. History is neither utopian nor anti-utopian.