In the footsteps of Pierre Huyghe, Philippe Parreno and Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, who are among the leading mid-career French artists, and now younger artists such as Adel Abdessemed, Saâdane Afif and Yto Barrada, who have acquired international visibility, a young, creative and dynamic scene is emerging today in France, comprised of artists born between the mid-seventies and the early eighties. This scene is just starting to be shown in Paris at ARC/Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris, Palais de Tokyo, Plateau and Espace Ricard. Some are emerging from art schools such as the postgraduate school at Paris La Seine, Palais de Tokyo’s Pavillon, or the École des Beaux-Arts in Lyon. This promising generation is characterized by strong diversity, influenced on one hand by a firmly rooted conceptual heritage with practices that combine cinema and music, and, on the other hand, by a formal generosity and a return to sculpture; many works explore questions of identity and cultural heritage specific to French history, in particular in relation to Algeria.

Within the first conceptual lineage, Marcelline Delbecq, born in 1977, works with texts and sounds, giving shape to audiovisual collages that are infused with sensuality and explore the boundaries between reality and fiction. Coming from the Pavillon at the Palais de Tokyo, a place led by Ange Leccia, teacher of the Parreno and Gonzalez-Foerster generation at the Grenoble School of Fine Arts, Delbecq has developed a narrative world where words and sounds combine to create mental images. Inspired by the photographs of William Eggleston, she creates posters on subtly shaded blue backgrounds, evoking possible stories for Eggleston’s anonymous characters. In the sound installation So Long, Delbecq whispers a text related to a portrait of Marilyn Monroe by Inge Morath; whereas in Solo she recomposes the song My Woman from Tokyo by Deep Purple in the form of a haunting and sensual poem. Using an aesthetic influenced by cinema, her neon work Silence Plateau alludes to imagined films. Silence, here taking the form of text, becomes a frozen opening sequence for a movie.

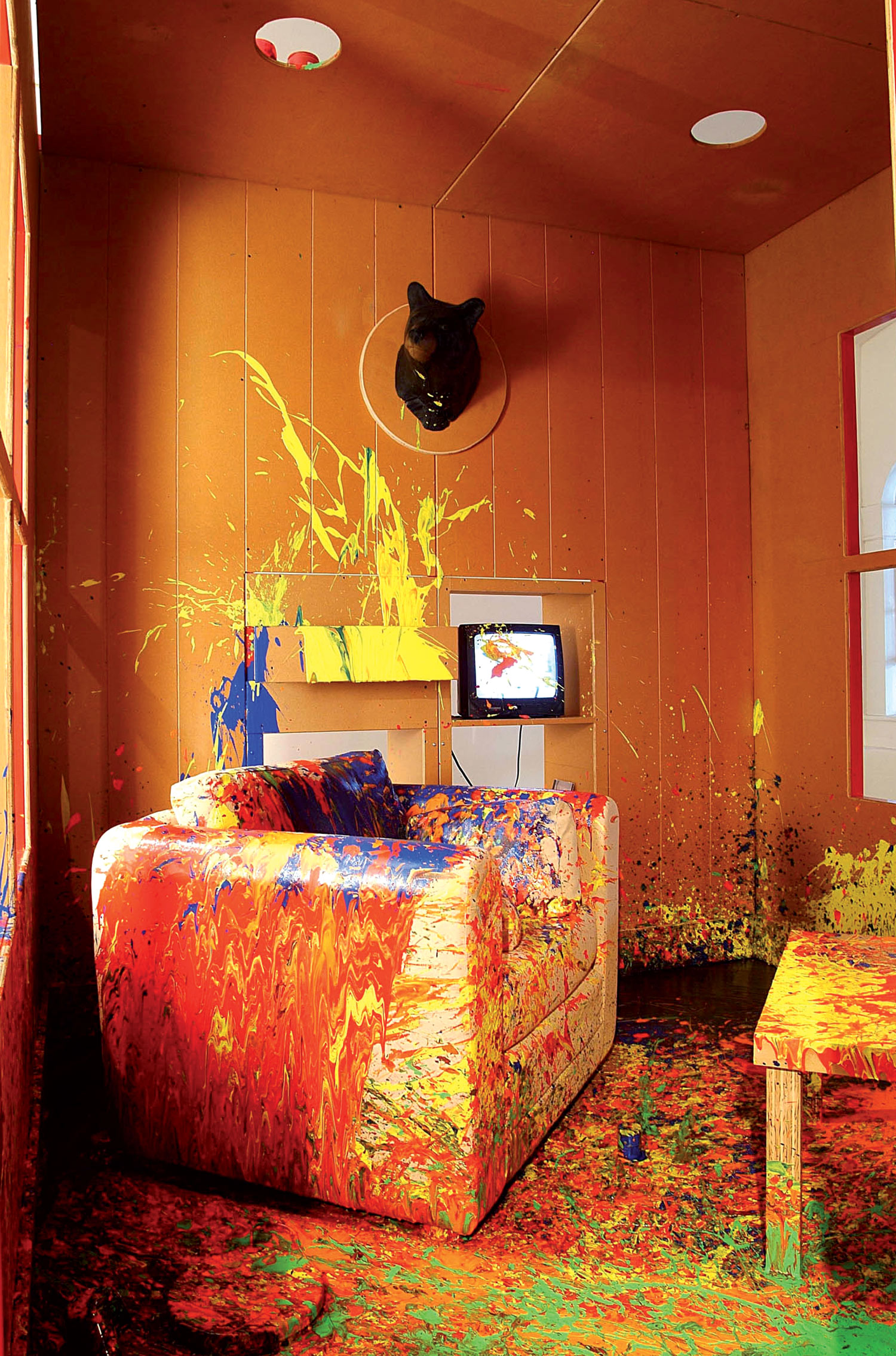

Through his imposing voluminous installations geared to modify our perceptions of space, Vincent Lamouroux, born in 1974, makes low-fi aesthetic environments that address notions of architectural utopias. His Sol #2, a site-specific work made of undulating wooden boards, turned Spencer Brownstone Gallery in New York into a sort of skateboard park. Lamouroux has also invented mobile objects such as his hybrid racing car that can be driven by visitors or his Pentacycle, a vehicle invented to travel the experimental track of the Aerotrain near Orléans — a concrete monorail that was abandoned before being used. For his recent exhibition “Grounded” at the Crédac in Ivry, a vast installation of 200 square meters, he reconfigured the space by creating a minimal wooden and neon ceiling. In Scape, made for the Mamco in Geneva, a steel rollercoaster deprived of cars loomed for a hundred or so meters between the walls of the museum, opening up an imaginary world reminiscent of sport and video games. Inspired by the bicycle experiences of Albert Hoffman, the Swiss chemist who invented LSD, this work was paired with a group of photographs concerning improbable private roller coasters (The Wheel and The Way).

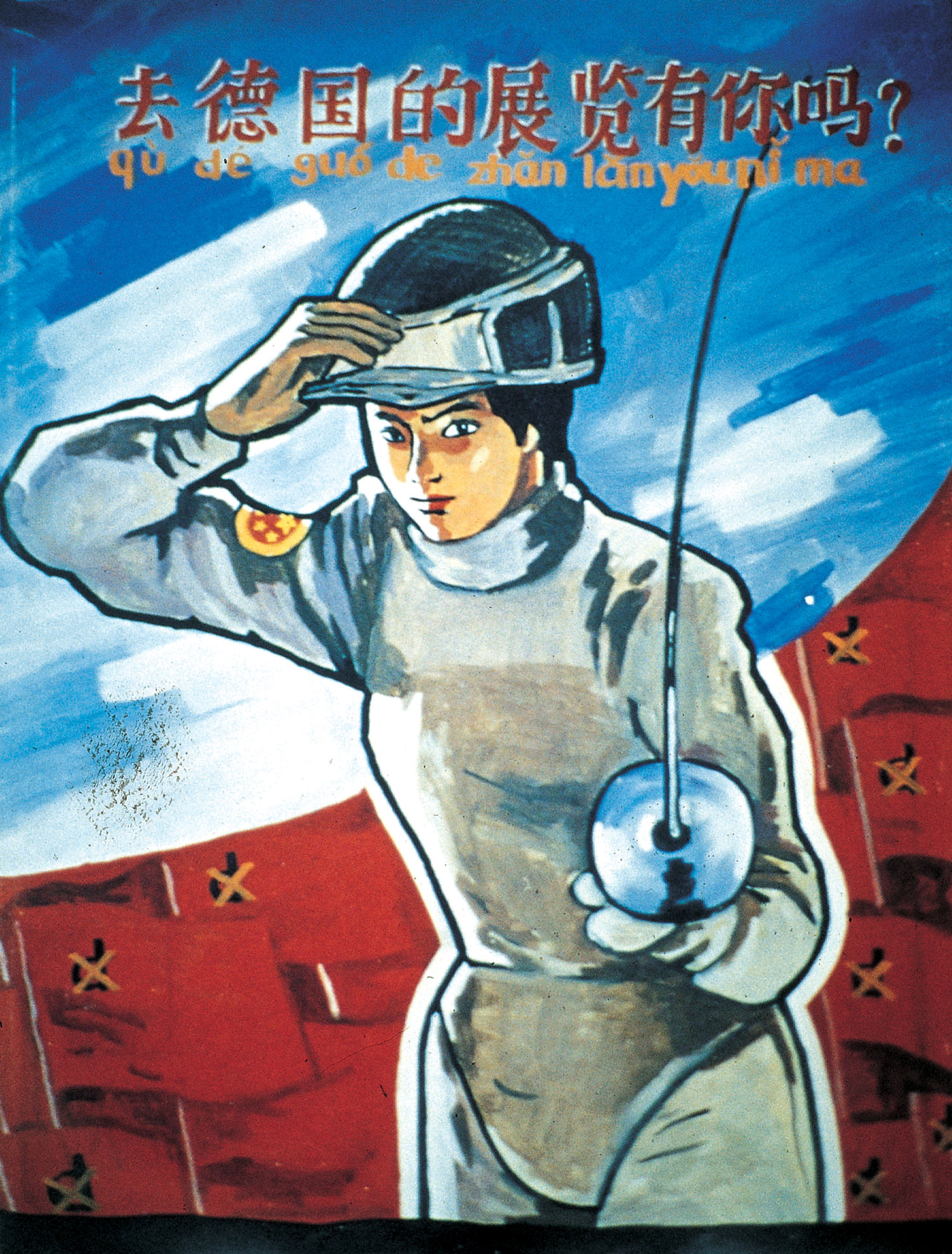

Loris Gréaud (born in 1979), one of the most prolific young French artists and winner of the Ricard Prize in 2005, offers a work of great maturity that conveys an interest in interdisciplinary collaborations with musicians and scientists, and plays with collective pop images. Physical phenomena have inspired several of his works, whether they be sound phenomena (reverb, infrabass, the Doppler effect), visuals (the Dreamachine, flicker effects), smells (the smell of the planet Mars) or more mental phenomena (hypnosis, telepathy). The installation Eye of the Duck, a habitation unit for ducks, also became a place for the spreading of rumors, broadcasting a text by David Lynch on cinema and on his “eye of the duck” filmmaking technique. His CFL (cognitive feeding laboratory / compact fluorescent light) ready-to-eat watercress plantation was endowed with a high level of a special molecule allowing for the acquisition of sharper night vision. More recently, his towed sculpture, inspired by the famous sacred mountain in Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind, was driven around Paris like a cinema extract made real. For the show “Notre Histoire…” at the Palais de Tokyo, he made an inflatable sculpture that flew up into the Parisian sky a few weeks after the opening, revealing its identity as an air balloon while resuscitating Jules Verne-like fantasies. With impressive prolixity, he recently planned an exhibition that took place in several cities, entitled “Illusion is a Revolutionary Weapon” after William Burroughs. In London, he made the smallest exhibition in the world and entered into the Guinness Book of Records; in Los Angeles he made the exhibition disappear; in Tokyo’s Omotesando he demolished a building in accordance to Gordon Matta-Clark’s 1975 piece Day’s End; in Milan he operated window blinds in time to a Steve Reich sound track. In New York, Gréaud presented a project within the Swiss Institute’s telephonic exhibition. Dialing a special number gave access to the work: vocal sample remixes of Burroughs, Schwitters and Raudive. Gréaud, the artist of this group most obviously influenced by the work of Pierre Huyghe and Philippe Parreno, renews interdisciplinary practices in which the conceptual combines with the experiential.

Guillaume Leblon, born in 1971, is a former student of Bernard Frize at the Amsterdam Rijksakademie. He graduated from the École des Beaux-Arts of Lyon and has mostly lived and exhibited outside of France. Referencing Minimalism and Conceptual art, the work attempts to reveal the traces of the real and to question, in a sophisticated manner, the very issue of representation. Contours, a candelabra redesigned in neon light, retains only the object’s outline, whereas his gigantic tree presented at the CAC Brétigny, hanging from the ceiling a few centimeters off the ground, was a reconstruction of the original as a life-size sculpture. His 16mm films also bring together architectural elements, such as his film made at night in the Villa Cavroix in Roubais, a structure initially conceived by Mallet-Stevens that has been submitted to the insults of man and time. During a boat trip he filmed April Street, a melancholic movie that surveys the half-submerged flooded town of Fontaine-sur-Somme. Suspended time invites a haunting dream state at the heart of natural disaster. Natural phenomena, as with architecture, are a part of Leblon’s favorite themes. Finally, with his mini models, his “Hybrid-Objects,” Leblon imagines architectures that he presents in storage boxes, as a kind of counterpoint to his more monumental work.

In keeping with the younger generation’s renewed interest in drawing and sculpture, Vincent Olinet (born in 1981) uses black humor to revisit popular culture, adopting Disney heroes and reworking fairytales with a sculptural virtuosity. His caustic humor betrays the naïve appearance of a drawing in which Bambi says to a little rabbit: “Hey, why don’t you go fuck Snow White?” For him the apparatus of the ‘spectacle’ has jammed and the last scene replays in a loop. Après Moi le Déluge (After Me the Flood) was the title of his polyurethane boat which filled with water in a gallery of Lyon, his birthplace. This trash version of Noah’s Ark mixes luxurious polystyrene and glazed sugar cakes that attract as much as they disgust. “One feels that all the will in the world as been put into them, but all that the visitor retains is this vague feeling of a failed party, of sugared excess, of heaviness for something that should necessarily have been a success.” In My Bakereï, the muffins crumble abjectly off shelves, while somehow retaining their appeal. For a solo exhibition in Paris, Olinet presented Chemin de Faire, an installation made of disconnected train rails. Combining them with a checkered array of images culled from railway signals, he emphasizes an inherent lack of movement. For this installation he also made hundreds of drawings on the floor and wall that evoked a vast playing field.

Zoulikha Bouabdellah, born in 1977 of Algerian parents in Moscow, lived in Algeria until 1994 . In her video work she revisits the East-West conflict and the condition of Muslim Arab women, offering a complex view of the Creolization of postcolonial Europe. In her video Dansons (Let’s Dance), inspired by Delacroix’ Liberty Guiding the People, a woman, dressed with a scarf in French national colors and embroidered with coins, sways to the rhythm of an Oriental dance. As the artist suggests, today it is less about “marching,” as the French Marseillaise hymn tells us, than about dancing to celebrate, in laughter and sensuality, the cultural mix that is reconfiguring France. In La Robe (The Dress), a white dress transforms into a black grieving outfit while the soundtrack broadcasts women’s cries mixed with joy and despair. In this way Bouabdellah evokes with subtlety the violence done to women. In Croisée-F-Crossing the artist shows a close-up of a woman’s veiled face; she slowly pushes the material away from her mouth to reveal a rosary. After five minutes, a Christ appears, evoking the question of crossed identities or principles that determine ways of dressing and habits. On a recent visit to Northern Africa she made A Petite histoire de la photographie à Casablanca (A Brief History of Photography in Casablanca), inviting passersby to photograph themselves in a tent with typical decorative patterns. In the midst of resurgent racism, when one French person out of three declares himself to be racist, Bouabdellah provokes reactions that are today more topical than ever.

One article is not enough to describe this new scene, which should also include Alexandre Ovise, Ziad Antar, Laurent Bechtel and Davide Balula. Less inclined toward English terminologies, the French scene does however show the emergence of new YFA, who, already supported by institutions and galleries, await their own Saatchi.