“Aperto ’93,” curated by Flash Art editor Helena Kontova and twelve other critics and curators active with the magazine, was an unprecedented rhizomatic exhibition that brought together the polyphony of the globalized world into the context of the Venice Biennale. Kontova revisits the exhibition in dialogue with Hans Ulrich Obrist.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: Let’s start from the beginning: where did the idea for a large-scale exhibition conceived as an archipelago come from?

Helena Kontova: Thank you for remembering that concept, of the exhibition as archipelago, which you developed on the occasion of “Utopia Station” at the 2003 Venice Biennale, and which is very important to me. Édouard Glissant, the creole writer you presented then, put forth an interesting and important idea that I think influenced, and is still influencing, the curatorial methodology of biennials and other large exhibitions: namely, the concept of mondialité, as a production of differences that accentuates global dialogue. According to Glissant, biennials were formally more reminiscent of imposing continents than of archipelagos, which are receptive and much more suited to exchange and sharing.

The idea of “Aperto ’93,” a true show within a show, was born instead from the notion that building an exhibition that aimed to be representative of the contemporary globalized world and its multitude of voices couldn’t come about through the expression of a single curator imposing their own vision onto others, but had to be something more like a magazine issue. A magazine issue is a polyphonic platform. Similarly, “Aperto ’93” provided a pluralistic perspective and access to a slice of the world in its authenticity. It wasn’t just a sole curator, or a curatorial team, debating the concept of the exhibition or who to invite to it; rather, many curators were given the freedom to represent their own ideas. In terms of its curatorial dynamic, the exhibition embodied the Deleuzian concept of the rhizome, as an opposition to the Western “teleology” of the center and the one.

Moreover, as a representation of the globalized world, “Aperto ’93” expressed the necessity not just of including a polyphony of voices, but also of giving space to often dissonant minorities, and bringing to Venice the artistic innovations that were then developing from New York to Shanghai, London to São Paulo, Tokyo to Los Angeles, Milan to Sofia, all the way to Bangkok, Teshie (Ghana) and Freeport (Bahamas).

HUO: What were the most memorable moments of the exhibition?

HK: It was the first time that you could admire the work of many protagonists of the ’90s art scene in a major international exhibition such as the Biennale: artists like Damien Hirst, Maurizio Cattelan, Matthew Barney, Rudolf Stingel, Gabriel Orozco, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Pipilotti Rist, John Currin, Andrea Zittel, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Renée Green, Carsten Höller, Sylvie Fleury, etc., were all present.

Damien Hirst’s participation was also the subject of a dispute between Matthew Slotover and Jeffrey Deitch, and in the end Slotover won.

There were many memorable moments. The works that caused the most uproar were definitely Hirst’s Mother and Child (Divided) (1993), a cow and a calf surgically cut in half and immersed in tanks of formaldehyde; but also Cattelan’s operation, which consisted of selling his space at the Corderie dell’Arsenale to a famous cosmetics company, and that of Tiravanija, who served plates of pasta to visitors during the days of the opening. And then Yukinori Yanagi’s The World Flag Ant Farm Project (1990), in which sand-filled boxes depicting the flags of all the countries in the world were connected by plastic tubes inhabited by billions of ants transporting grains of colored sand from one flag to another.

HUO: How were the curators chosen?

HK: The selection criteria for the curators were quite alternative and innovative. We wanted to represent the various roles in the art world, not just that of the curator tout court. So there was an artist-curator (Thomas Locher), a gallerist-curator (Jeffrey Deitch), magazine editors (Francesco Bonami and Matthew Slotover) and critic-curators like Benjamin Weil, Nicolas Bourriaud, Robert Nickas and Berta Sichel. They were all very knowledgeable people, who were able to respond to our invitation to present a snapshot of the state of art in its most advanced forms and expressions.

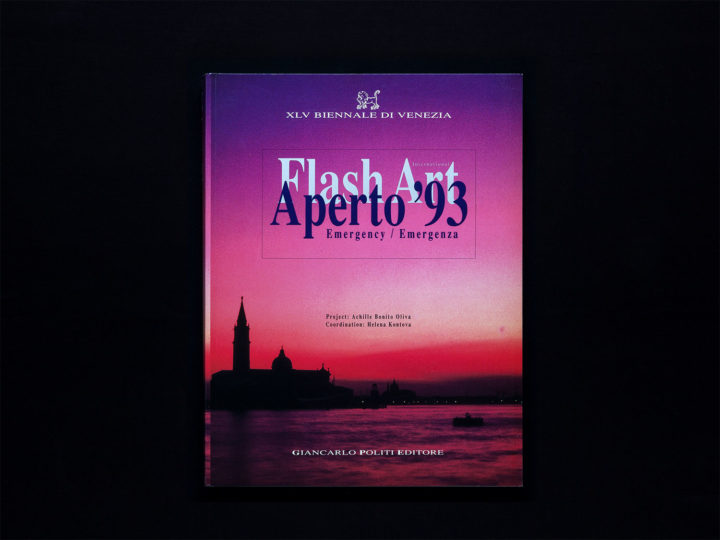

HUO: Anthony Powell has written that “books do furnish a room.” Can you talk to us about the exhibition catalogue?

HK: “Aperto ’93” was built like a three-dimensional magazine issue. When you plan a magazine issue, you can’t exactly foresee the results, and the exhibition thrived on that same kind of unpredictability. It was an exhibition that left a lot of space to chance. In a magazine you can cut or edit texts, but artworks have to follow their own autonomous and unpredictable path. All that worked in favor of experimentation, of the idea of the workshop and the open work (which is, incidentally, where the title of that Biennale section came from).

The exhibition catalogue was composed of the essays written by the individual curators, but also of theoretical essays that they selected. For example, Thomas Locher chose an essay by Ernesto Laclau on the problem of identity in the contemporary world, and Nicolas Bourriaud chose one by Serge Daney on the representation of the Gulf War. There were also essays by writers such as Akira Asada, who criticized the manifestations of the postmodern in Japanese culture, and by Slavoj Žižek, who engaged in an analysis of the Balkan Wars and theirs effects on the global imaginary; there was also my interview with Julia Kristeva on the depression and remapping of Europe.

HUO: Were there any projects that went unrealized?

HK: If I remember well, we managed to execute all of the projects. Partly because we solicited the participation and engagement of numerous institutions and galleries. There was an enormous sense of anticipation and solidarity surrounding the show. In some respects we even managed to defeat the bureaucracy and the Venetian customs office. And then, participating in the Biennale was a unique moment in the careers of both the curators and the artists, who were all little more than twenty-year-olds at the time.

HUO: The exhibition reunited many artists and created a lot of new encounters. What new collaborations followed from it?

HK: I think that for many artists and curators, “Aperto ’93” was maybe not exactly a springboard, but certainly a further legitimation. Moreover, most of the curators, even those whose first incursion into curatorial practice was “Aperto ’93,” continued on that path and in many cases opted to devote themselves to curating. The most important thing is that “Aperto ’93” became a model for many future events, from the Johannesburg to the Moscow Biennials, from Gwangju to the 2003 Venice Biennale curated by Francesco Bonami, in which “Utopia Station” — which you realized in collaboration with Molly Nesbit and Rirkrit Tiravanija — represented a continuation, a deepening of “Aperto ’93.” With “Utopia Station” you brought new developments to that curatorial methodology, above all from the point of view of temporality, making the exhibition space even more participatory.

HUO: How was the exhibition received by critics?

HK: As is almost always the case with something new, the mainstream press was mostly negative, criticizing its fragmentariness, as well as the choice of certain artists. But we got mostly positive feedback from the specialized magazines — foremost among them Artforum, which referred to “Aperto ’93” as “the better Biennale.”

HUO: Did the show have a particular layout?

HK: It was the first time that the entire Corderie dell’Arsenale was used. We didn’t put up rigid divisions between one artist and another, which had been the norm until then. In “Aperto ’93” the location was managed like a sort of open space, where the artworks could communicate with each other. We gave life to a liquid space more suited to the works exhibited, which were often interactive and in constant dialogue with each other and/or the observer.

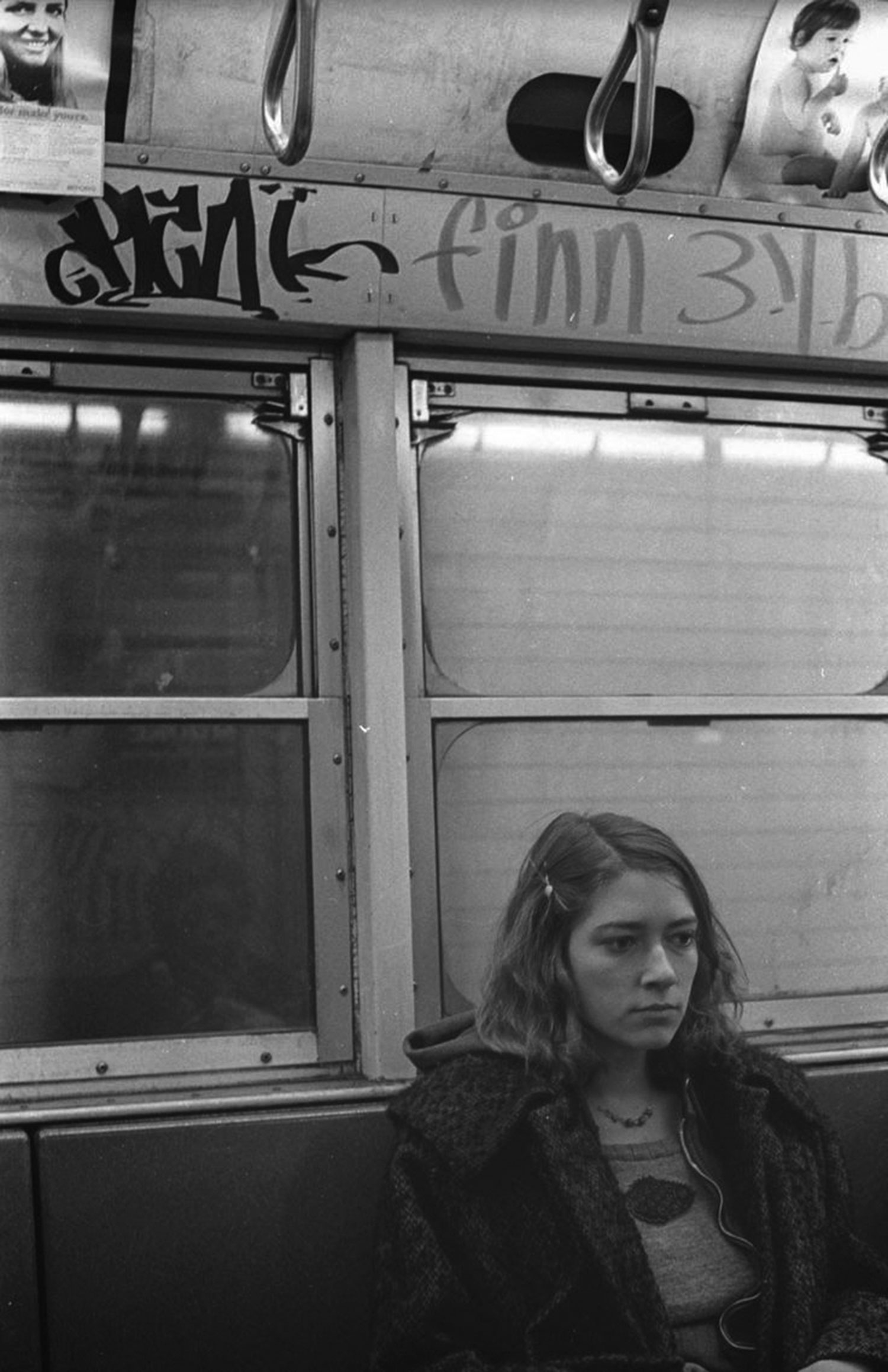

Even the videos were integrated into the exhibition and no longer confined to dark rooms where they could only be seen at certain scheduled times. It seems banal today, but in 1993 it was rather revolutionary. Benjamin Weil’s project, for example, took place in the city, on the boats, with contributions by Henry Bond, Sylvie Fleury, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Gotscho and Lothar Hempel. In other cases, artists intervened in the gardens of the Biennale.

HUO: What were the best and worst moments of the project?

HK: The fact that all of the curators and artists we invited accepted right away and enthusiastically was surprising. Also, Achille Bonito Oliva, the artistic director of the Venice Biennale that year, was very happy with the project, even though it wasn’t completely in line with the curatorial methodologies of the time. The most moving moment was probably finishing the installation of certain works that were particularly difficult to execute and transport into the Corderie.

The worst moment was definitely the business of the catalogue, which was confiscated by request of the editor of the general catalogue of the Venice Biennale, who wanted exclusive rights to all of the Biennale-related publications. While preparing the catalogue, we had repeatedly informed the artistic director, Bonito Oliva, of our decision to publish a book on “Aperto ’93” independently, as Flash Art. In the end, we had to appear before a judge with a document signed by all the artists and curators, stating that they had produced all of the published material exclusively for the catalogue edited by Flash Art. In light of these statements, the police gave us back the catalogue copies, which stayed in distribution for years, stocked by the bookstores of major international museums. The “Aperto ’93” catalogue is almost a cult object.

HUO: Anything else?

HK: Among the many positive and negative reactions there was also a protest by an animal rights group against the works by Yukinori Yanagi and Damien Hirst; and a visitor tried to “taste” the face of Janine Antoni’s chocolate sculptures. I remember that the Biennale organizers were worried because they weren’t used to such innovative art and the strong reactions it triggered. But in the end, years later, everyone recognized the incisiveness and beauty of “Aperto ’93.” The most important artists of the 1990s were all there. While I was on a boat in Venice during the opening days of the latest Biennale, I ran into a well-known gallerist from New York who, confiding in me his first impressions of the current exhibition, said he hadn’t found anything particularly interesting and remembered that one time there had been this incredible show… As the conversation went on, I realized he was talking about “Aperto ’93.”