For years now we have been witnessing a reformulation of social and political postulates that were created during the ’60s and ’70s. At that time a series of practices came to reflect a new manner of situating the individual in society, and to cast doubt on old ideas about the political. There were several methods of executing these postulates — performance art and happenings, body art and land art, video art and guerrilla television — as ways to claim a space for art that was understood not only as an individual expression but also as collective and political acts. From then until now, there have been many artists who have once again raised questions about the impact of the social on artworks. It may at first seem counterintuitive, but much of Terence Koh’s work has followed the same vein, although his capacity for creating individual mythologies has distinguished the more social and human aspects of his work.

Among those closest to Koh, both in terms of artistic production and his persona, he is perhaps seen as the legitimate son of that already legendary and mythical triad composed by Joseph Beuys, Andy Warhol and James Lee Byars: Koh’s work is a distillate of notions and reconsiderations present in their work, to which he nevertheless adds personal experiences, cultural transmutations and his own intimist, present-day worldview.

If we closely examine the artist’s oeuvre — which in the beginning was created under the alias “asianpunkboy,” related to the web site asianpunkboy.com, which he continues to use today as a medium for creation — we will realize that the idea of being able to distill personal elements at a social level is something that was already there at the beginning of his career and continues to this day. It is worth remembering that this website — where Koh presents himself as a rabbit, the artist’s fetish-image — is itself a labyrinth or a rhizomatic website where a photo, phrase or drawing can take you from one part to another without following the same route twice. Throughout this journey the notion of loss is permanent; the user/individual is engaged in a kind of perverse game wherein references, desires and experiences become a hypertext that consolidates the idea of the personal through the magnitude and great speed of change on the web, in the same way that we experience the real-life game of mass society, overflowing with stimuli.

Koh’s work stems from the formation of a character that never stops creating and recreating, mutating time and time again, as evident from asianpunkboy’s content — including information on the many cities where he was born and his many birth and death dates, occupying in this way the different artists into whom he has secretly transformed. All this has been tacitly used by the artist as a metaphor of what there is and what there should be. It is worth remembering the diverse exhibitions that Koh has undertaken in his gallery, the Asia Song Society (ASS), a space that takes pride in exhibiting Asian artists and which is located on the first floor of Koh’s Chinatown home, where he also acts as the organizer and sometimes manager of his own club (located in the basement). Koh describes it as more of a sentimental club, which he opens and closes depending on his mood. Both places — both acts — engage the social; guests include neighbors, youths, Koh’s fans and family. Both personal places stem from public, social and collective spaces, and the artist’s character is converted into a kind of container for content, both individual and collective; this is due to Koh’s eagerness to reach not only everyone outside the limits and very channels of the art world but also to reach those that are within his world. He intends to reach everyone from the sphere of the social.

Yet Koh’s creativity is not about the construction of a character. Rather, it is an act of political or social relevance with an ever-growing surrounding collective subconscious; a subconscious that acknowledges adolescent universes, gay perversions, diverse cultural spiritualities, cool fetishes, trendy patterns, the world of art and technology, all of which Koh repositions with great sarcasm and irony, as well as introspection, into a kind of individual evasion that is at the same time invested with a collective and social dimension. Koh is also a great strategist: his stances on art and life find expression inside the art world but at the same time want to subvert it; his works are never indifferent to the viewer — who may find him or herself lost, incited, questioned, confused, blinded or even forced. None of this is done by Koh in an explicit or direct fashion.

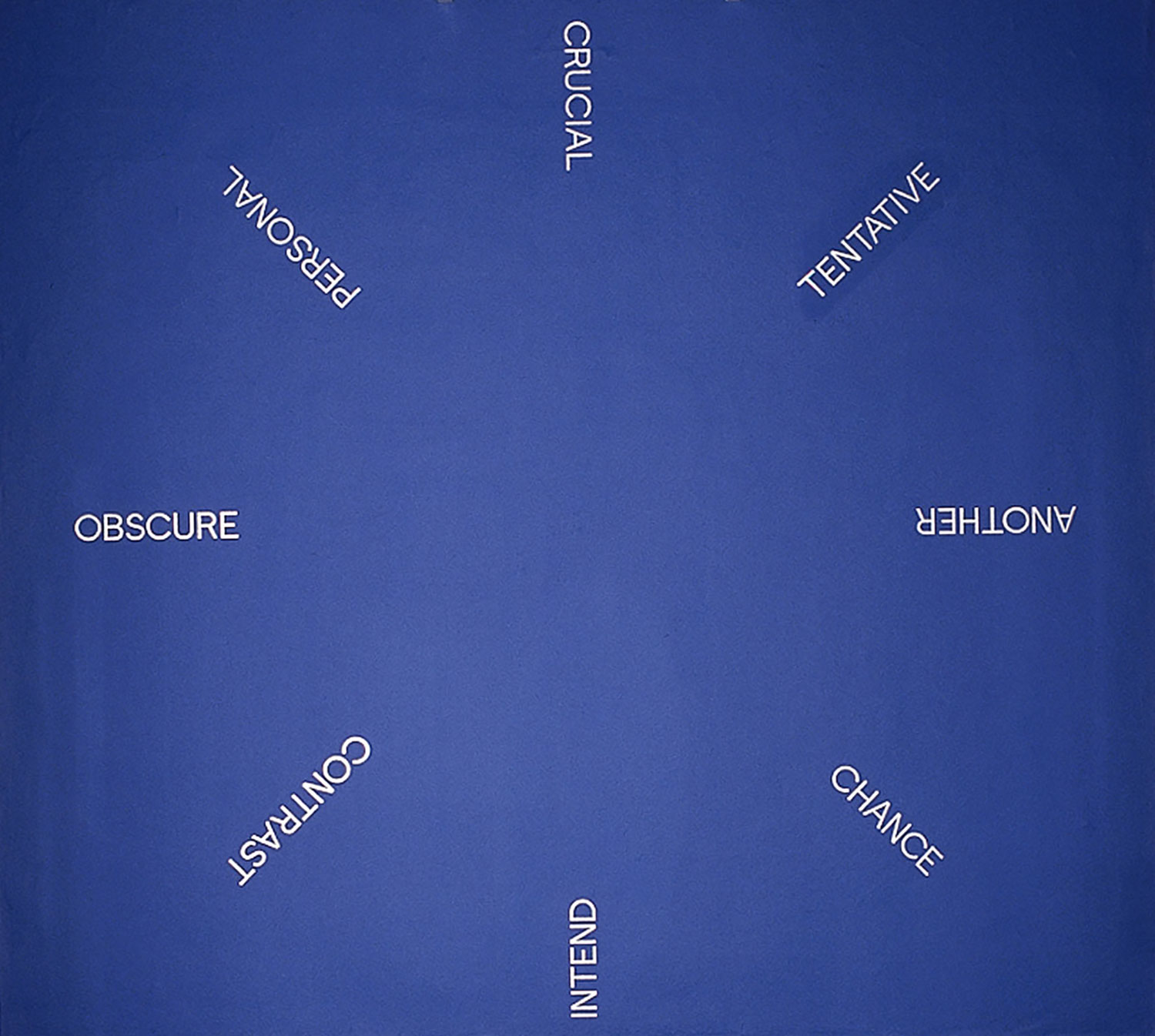

Koh’s subversive adolescent dreams began with his first great white installation called The Whole Family (2003). From the start of his career he understood the political as a countercultural space, a space for desire where the proposal of subversion — symbolized by inverted artworks — came to express the dream of freedom, of sex and desire and new ideas about what family means to each of us. Other works develop this political undercurrent in a subtle and almost minimalist way — including the two spheres that nearly touch each other in photos, drawings or installations — implicitly suggesting the work of another great artist, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, in whose work chance, fragility and desperation are apparent.

In Koh’s most recent works as well, his strength resides in the radicalism with which he expresses non-conformist attitudes, some of which may lead society in general to wonder if the stance Koh takes is for the benefit of media controversy. For example, Koh places us next to Bruce LaBruce in his Dick Cave (2007), a place for meeting, a kind of cruising bar. If Felix Gonzalez-Torres speaks to us of diaristic time in a cool, geometric fashion, Koh, in a resounding way, introduces us to his cum paintings: black canvases stained with champagne, semen and sweat that, together with their date of execution, expose the site of the artist’s orgiastic actions in what is akin to a political act. Similarly, his film God (2007) features a man dressed as a geisha engaged in bacchanalian acts, as well as the artist having sexual relations with another man who is clearly penetrated from behind. The same can be said for the works where a series of religious elements are brought into play, dealing not only with Christianity but also a range of de-codified signifiers. In his installation Captain Buddha (2008) he used the iconography of the swastika, a peace symbol and toy soldiers. Or the infamous exhibition “Gone, Yet Still” at the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art in Gateshead, England, in 2008, in which phalluses were attached to plaster casts of iconic figures like Mickey Mouse and Jesus Christ; although there was little public disapproval, the case still went to court, expressing very clearly the reach of contemporary art when appropriating culturally loaded symbols.

Koh’s work will always have a sense of mystery and alchemy that becomes manifest the moment it is exposed to the public — the world that the artist does not belong to but manages to transcend with his art. Already the list of works that confront politics, violence, war and, of course, death, is almost endless.

Koh carried out his own tribute to Picasso’s Guernica with What then is time? I know well enough what it is, provided that nobody ask me? (2008), presented at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León (MUSAC), Spain, for his solo exhibition “Love for eternity.” In similar fashion, he paid homage to Goya, reinterpreting the brutalities that the master depicted in Los fusilamientos del 3 de mayo (1814), though Koh did it in a performative way with The End of My Life as a Rabbit in Love (2007), where a troop of children dressed in white appeared to carry out a similar act with the artist. Death is, in essence, a leitmotiv in Koh’s work that is equated with absolute freedom, where life and disappearance are confused. Koh’s “love for eternity” is returned to us in a universal way that each time seems more utopian in these troubled times that we experience in different parts of the world.