I have often heard others make a distinction between “the artist” and “the person” when talking about their interactions with a given artist. It’s a way to reconcile the gap that can exist between the exceptionality of their work and our potential disappointment with them as a human being — or vice versa. For a couple of years I had been trying to meet Tarik Kiswanson, but, even when we were in the same city, it had never been possible. Because of my immediate empathy with his work, I had come to imagine Kiswanson “the person” as someone who would share my desire to exchange thoughts, ideas, and knowledge. When, finally, the occasion came to have this dialogue via Zoom, it was exciting to find that in this case “the artist” did indeed coincide with “the person.” Kiswanson’s approach is to start with the very fundamentals of form; the matrix of things he works with leads me to think of his practice as a semiotics of the elusive image. Therein lies his authenticity: his constant attempt to arrive at the origins of form in relation to a self that is in a perpetual state of construction — or unveiling in a certain sense. His output, with its strongly formal impact, is the result of an ethics of production, a determining condition in Kiswanson’s attitude toward art. It is a process of seeking to (re)construct the self as a primordial entity that is reflected in its most “pure” forms. In the dialogue that follows, Kiswanson and I address the meaning of his work, ancestral ideas about life, and where art is located.

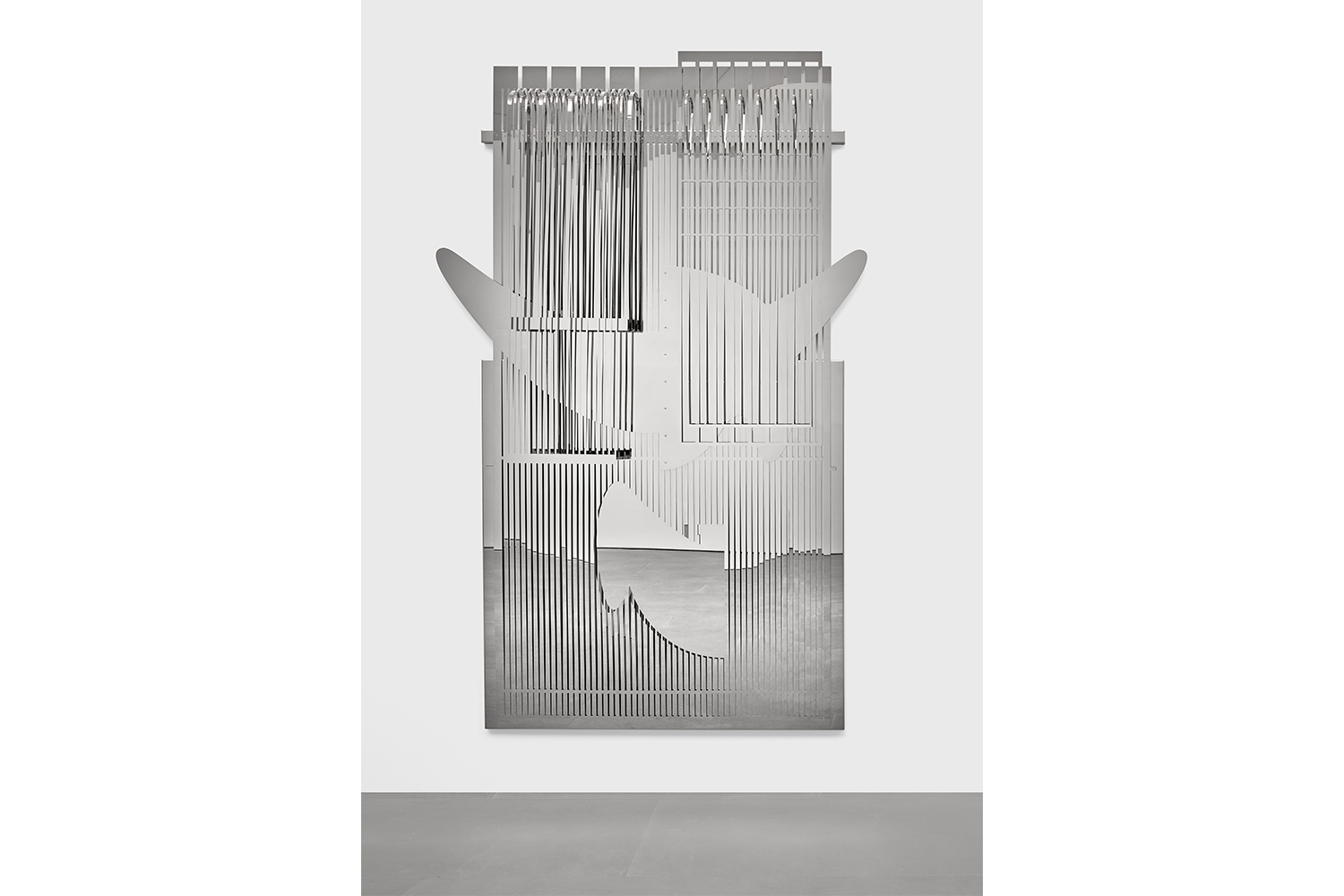

Eleonora Milani: There are two different dimensions that strike me about your work. One is a formalist quality — your ability to shape forms into performative works. The other is this emptiness, this strong feeling that I get through works like the “Father Forms” (2017–20). I would like to start by talking about the “Vestibules” series (2016), because in that series you almost define your whole practice. When I saw them in your 2021 retrospective “Mirrorbody” at Carré d’Art Musée d’art contemporain in Nimes, they felt like monumental totems. But then there’s this closed/open duality. There’s an empty space but also a full space.

Tarik Kiswanson: Well, it’s a negative in the positive somehow. These works you mentioned are the largest works I have made. The forms I create are often open to a multitude of interpretations. In “Father Forms” and “Vestibules,” which are also two series that are interconnected, the self is the point of departure. The perpetually transformative state of the self, the fragmented self. I was creating works that shattered one’s reflection. You are fragmented on the surface of the work. Becoming a part of it, somehow participating in its creation. You see yourself endlessly, as broken images: multiple layers appear and disappear. And these works are very performative, engaging with everything happening in the space. They absorb the spectator but also the architecture, the changing light of the day, and when exhibited with other works they also absorb and fragment them. In this sense they function as a portal.

EM: Also the ambience they create, because you can feel the movement. There are vibrations within the works. They’re made of strips of hand-polished steel that spread out. It’s an opening movement that goes and comes.

TK: And then there’s this aspect that you can literally enter the work and activate it, become a part of it. These works open like big whirling Sufi skirts. Vestibule, the title of the work, is also the name of the organ in the ear that regulates our balance. I often speak about this idea of trembling when thinking about the self. The works literally make you tremble, sometimes to the extent where you feel nauseous. When you enter the work and when it is activated it disturbs the vestibule in the ear. Without this organ we would constantly be falling over or walking upside down. Ideas of stillness and trembling, opacity and light, are just some of the many formal words I use to speak of my own condition, that of a second-generation immigrant born in the suburbs of Europe.

EM: Talking about opacity, the “Vestibules” are so formal they’re almost like a post-avant-garde exercise. You know what I mean? When I saw this body of work, I immediately thought about all the artists who have tried to reverse avant-gardism using the tools of the avant-garde. You clearly do it without irony or collapsing it into itself. In your case it’s more like a return to archetypal form.

TK: I like this explanation. I’d say I like to strip away. My working process is very much about using reduction as a way of attaining complexity. But the paradoxical thing here is that the more you strip away the more the works become layered and dense. Stripping away makes things so much vaster.

EM: Yes. But at the same time, they include elements like shapes, opacity, brightness… a sort of power in the “work” itself.

TK: Yes, because my experience with making art is very physical. I am very close to the works because they are time-consuming to produce — this is an important aspect. They also stem from this physical relationship that constantly bends and transforms the outcome. They are born through philosophy and writing, but I also believe in the intelligence of the hand. I put my trust in my own sensorial and bodily experience. In my own perceptions of the world. How light constantly changes and how we physically move and displace ourselves are important sources of inspiration with which I can take the work further. Observation is essential because I’m not just talking about my own body — I’m also talking about the bodily experience of the spectator. How the experience of art and, as you say, the power of the work can be amplified. Art which comes from inside of us but manages to operate outside of us, far beyond ourselves.

EM: It’s really an ancestral idea.

TK: Ancestral ideas, but still essential questions. What is art and where are the limits of art? I try to go back to these old questions. I’m not here to answer them. But I think that my work somehow in its physicality tries to challenge these notions. Actually, many find my work unplaceable in relation to art history. It is perhaps because it is not nourished by art itself but by my own human condition. As time goes on the works are no longer dependent on a multitude of references and protocols but are born from within.

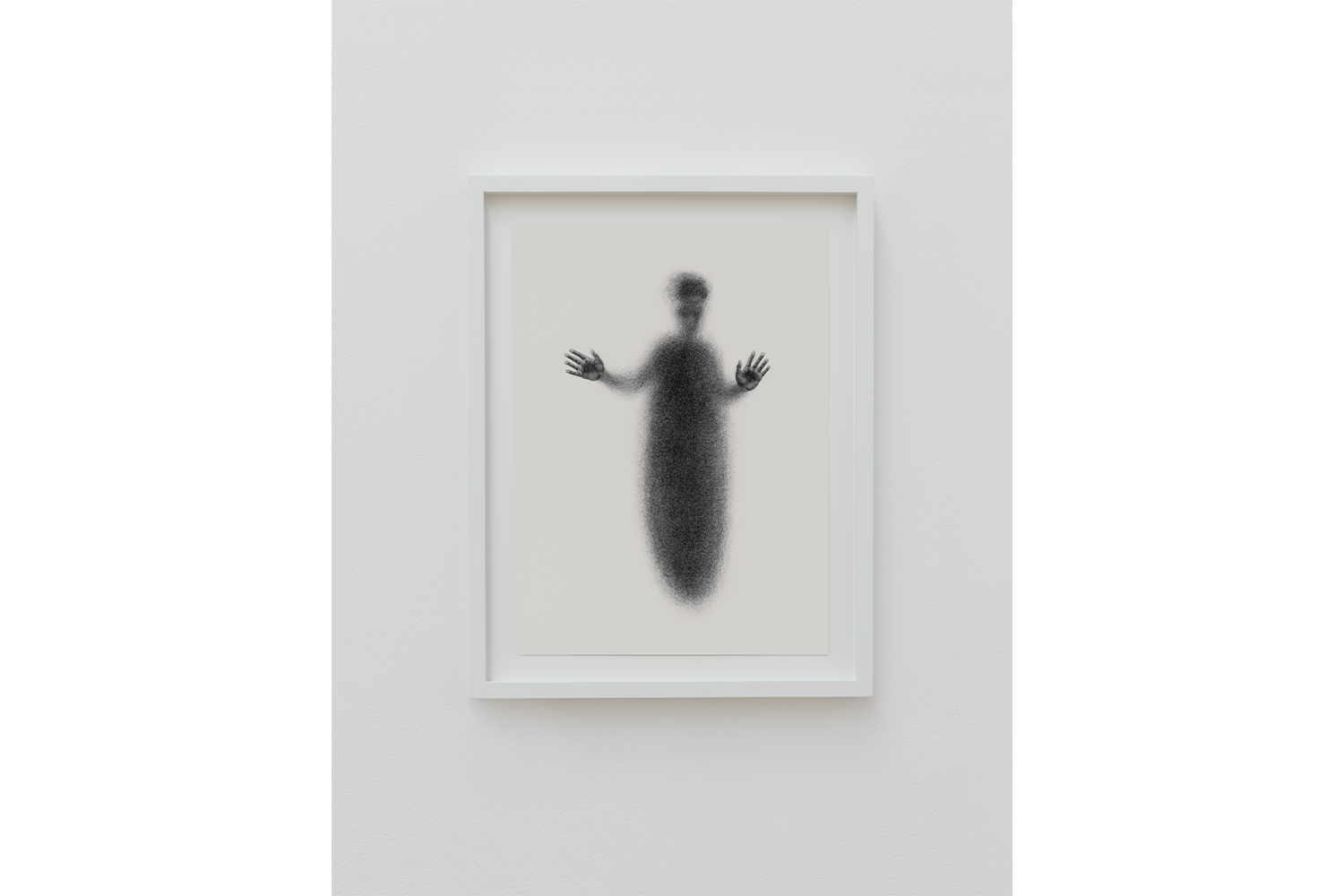

EM: This thing you say is true in respect to some earlier works. I am referring to 1951 and 1974 (both 2016), or Conductive Body (2019), which might have suggested a certain seriality in your production. Though there is nothing really serial in your practice, not only because you are committed to the idea of making things with your own hands, but also because of the pursuit of primal form in a way that has to do with interiority.

TK: I want to go back to speaking about emptiness. I think that with all of my work — and this even goes for newer works — the question of void is primordial. As I mentioned earlier, there is this idea of really stripping away all references from the work and observing it and looking at what remains. But one can equally say that the references are so many that they have created a dense web from which a form is born. I decided very early on as an artist that ambiguity was essential in how I wanted to make art. I avoided all kinds of preconceived notions about how a work should look. I didn’t want to make it easy for the spectator. I wanted people to look at these works, see their fragmented reflection, and ask themselves questions about what they’re looking at.

EM: This also happened to me when I saw Nest (2020). This kind of suspended egg, levitating, light, although you can feel the weight of gravity. It is truly formalist, but at the same time there is a sensation that it might vanish from our sight.

TK: It’s advancing and retracting at the same time. When creating Nest I was looking at images of cocoons, of bird and insect eggs and seeds, and I made several drawings of a shape that placed itself somewhere between all these references. So somehow this ambiguous shape is everywhere and nowhere. Like a deep condensation of everything I had been looking at. A shape that is charged with new interpretations, teasing the consciousness of those observing it.

EM: To me it was similar to how we could imagine life in terms of form. That was actually my first thought seeing Nest.

TK: But birth is life. I was perhaps attempting to create a shape that could talk about the universe. A form that speaks of beginnings, about life and death. A shape floating through history, constantly generating new interpretations. I don’t want to say that everybody can connect to the work, but I try to somehow go back to primary but ambiguous forms that can have perceptional and philosophical unfoldings in many minds.

EM: This need in your research is quite clear. I mean the need to refine the image, refine all the additional shapes, going back to point zero.

TK: And I think that this is also something I’ve been doing my whole life to understand my own condition, to go back to the source somehow. When you don’t know where you belong you want to understand where it all started. To go back to the point zero. This idea of turning inwards, going back to the source, the history of my family, the origins of my own identity as a second-generation immigrant born in Europe, has landed me in place where I further want to explore the human condition. My early works were dealing with highly personal subjects relative to memory and loss. These subjects are still very important, but I find myself also asking bigger questions. What is language? What are the body and identity really? And even what is art, or what could it be? I know it’s very huge, but these questions drive me.

EM: Well, it’s visible in the “Open Window” series (2021) and “The Window” series (2020), which I really love. But also in Respite (2021). The transparency and opacity — this kind of dualism — and also the void, are really strong in these bodies of work.

TK: I worked with different objects, some from my family and their exile, that I embedded into transparent and blurry resin casts. The work deals with questions like grief and loss. How memories disappear, get erased through time and displacement and how identity and culture are lost and must constantly rebuild. The resin works can be seen as a sort of memorial. Respite, for example, with a candle frozen the moment it’s melting away. A departing memory.

EM: These works are really touching. There’s even a sense of one’s own feelings being encapsulated in the resin casts with candles. That moment when you have to leave something but you don’t want to. It’s like an attempt to grab a final moment before it’s gone.

TK: Yeah, it’s resisting its own destruction, before vanishing into the void. There are many paradoxical ideas that go into the symbolism of a candle, and of course I am always interested in how one work can carry many contradictory ideas and invoke different feelings and interpretations. How many things can coinhabit the same work. We as individuals are full of opacity and light. We constantly oscillate between the transparent and opaque. What we share with the world and what we keep inside.

EM: Yes. By the way, I’ve always been obsessed with candles since I was a child. I would spend time observing and touching them. I was enchanted. Nobody could understand why I was so obsessed with candles. I still have this fixation.

TK: Me too. We share the same fascination. There is something very prehistoric about a fire. When observing a lit candle, I think we have something inside of us that reminds us of our primitive nature. It’s like when we speak about darkness and light, I imagine the very first moment a human made a fire. Again, something that takes us back to the beginning.

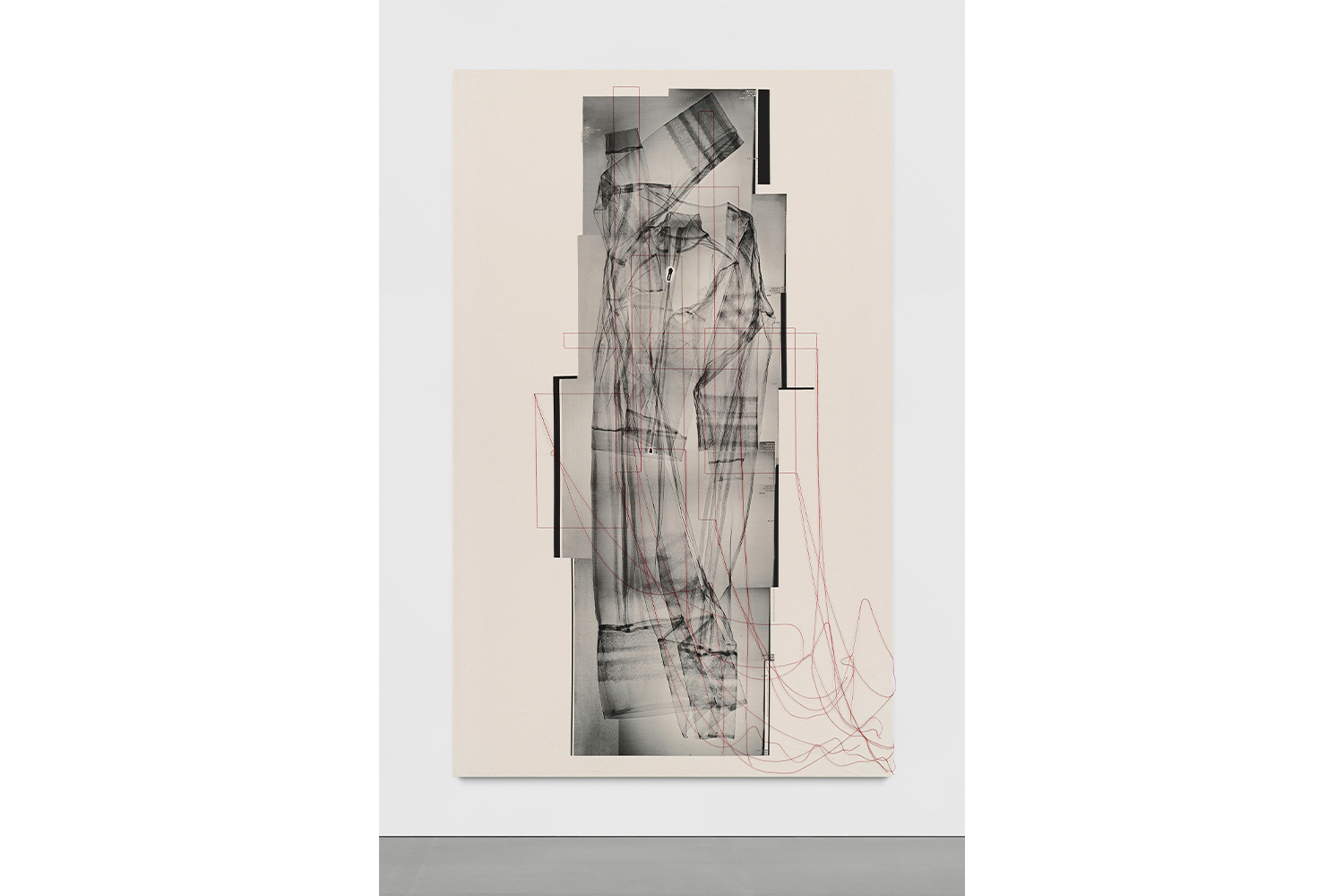

EM: I compare your disappearing candles to your “Passing” series (2020–22), because even here the works are in service to the form, although in this case the pattern comes from the fashion world. From a paper pattern that generates new shapes.

TK: It’s like creating a time capsule. When I was making the “Passing” works I was working in an X-ray clinic that agreed to let me use the machine at night when there were no more patients. In the images we see zippers and details from sportswear like Nike and Adidas melting and fusing with traditional dresses from the Middle East that are hundreds of years old. The overlapping clothes rendered transparent can be seen as a new sort of identity, one that carries multiple layers and stories simultaneously.

EM: It’s a sort of Warburghian approach.

TK: Yeah. There’s something Warburghian in this aspect. When I look into myself, I’m also looking into the history of migration, something many can relate to. As many references move through my mind, the finished work is often inexplicable even for myself. There are many things that get processed on a subconscious level. It’s out of my control. For example, I cannot tell you how exactly the work Nest was born, this shape exactly. I was sanding down the form for months, but at the end I don’t understand at what time I decided to stop.

EM: Yeah. It’s like you feel that it already existed in a way.

TK: Yeah. In a way, inside of me. Like it had always been there.

EM: When I saw the new iterations of “Passing,” I thought immediately of Nu descendant un escalier n°2 (1912) by Duchamp. I’m referring to Passing Mother (2022) in which you took the dresses from your mother that she inherited from her great-great-grandmother. Here you also introduced a figure.

TK: Many told me this. I think that there was always a figure there somewhere in my “Passing” works, but much more coded perhaps. In Passing Mother it was the first time I worked with my mother’s inherited traditional Palestinian dresses and my own clothes. In the images we see her dresses and my clothes layered together with dresses of women from the sixteenth century borrowed from the Konstmuseum in Halmstad. This is the city I was born in and where my parents exiled to in the 1980s. So you have these three identities that come together. When I started to compose the garments, there was something emotional in the process. I was looking at my family history through the images the machine was generating. I probably, on an unconscious level, wanted to give life, resurrect something, someone. And so this is reflected in the end result. In my case the body is not descending but ascending into opacity.

EM: And they are similar to Nest also.

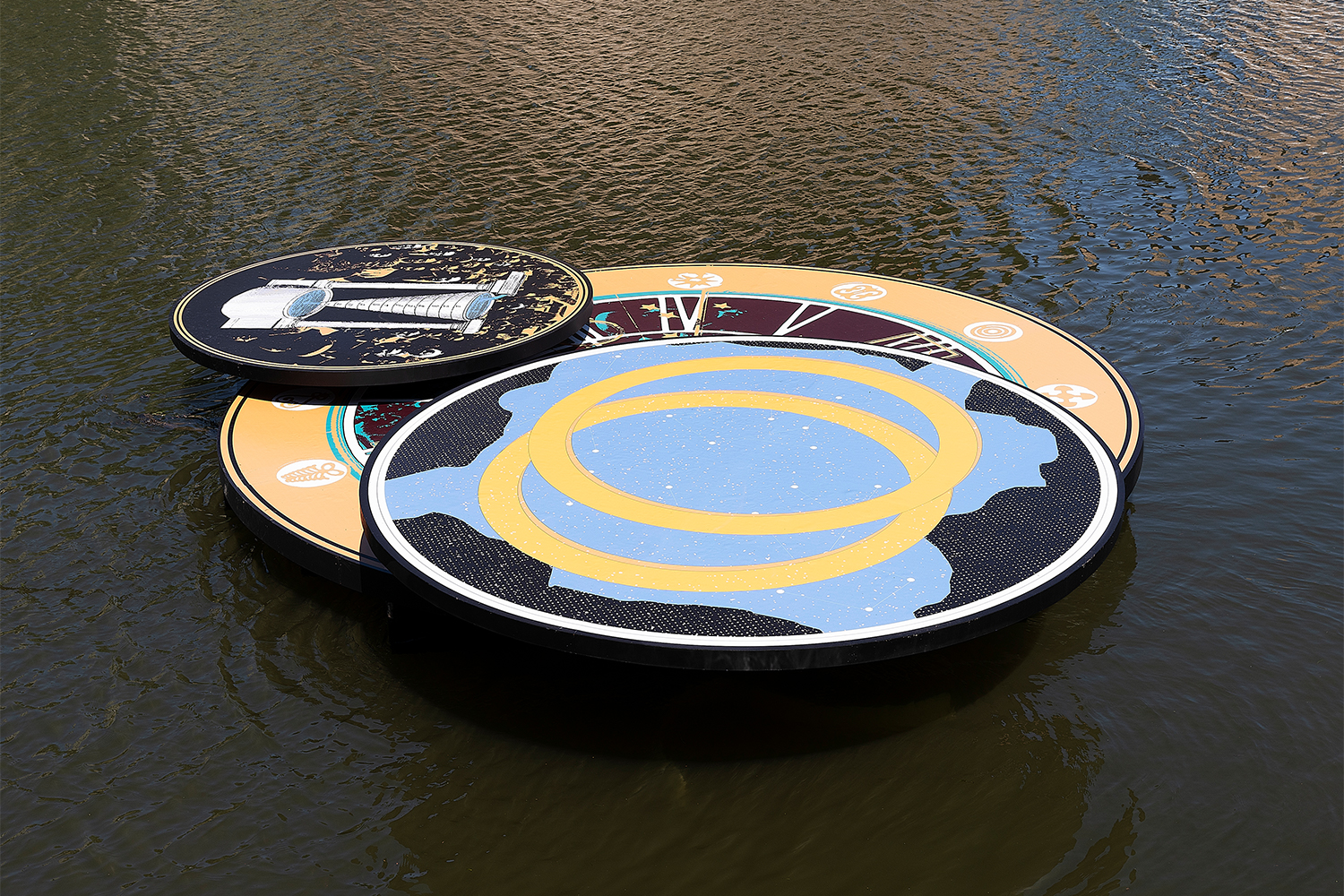

TK: Very much. I think that when I was composing the works on the table, and then hanging the images vertically I was thinking about levitation. This was the central theme of the exhibition “Mirrorbody” at Carre d’Art – Musee d’art contemporain, where I used levitation to speak of rootlessness and loss. This was also in the back of my head when I produced these new X-ray works like Passing Mother. And, of course, the idea of levitation comes back in Nest. It is also very present in the film The Fall, in which a boy is hanging in mid-air as he falls backwards from a chair in slow motion.

For perhaps the first time, I think we are in a situation of great uncertainty. We don’t really know where we’re headed. Everything is kind of suspended in a levitating state. Are we near the end or at the beginning of something new? The migrant doesn’t know where he is headed. Perhaps this is the way in which my work opens up to universal questions of home and belonging.

It’s something that I’m exploring in a lot of upcoming projects, also for the 16th Biennale de Lyon. Furniture that has lost gravity and stuck to the ceiling. Everything being in a static, uncertain situation. What does it mean to exist in between different contexts and conditions? Physically? Psychologically? This uncertainty being something that concerns all of us.

EM: Very often now, we’re talking about transdisciplinary or multidisciplinary works — working between different jobs. But what does that actually mean?

TK: Yeah, what does that entail? I don’t really think about it as “in between.” What drives me to work in a multidisciplinary way is the message. I move across different disciplines because the subjects that lie at the core of my work constantly push me into new territories. Levitation being one of them.

EM: What do you think about this topic nowadays of the artist’s personal life and identity compared to the work? Today we’re discussing this topic a lot. There’s a critique that says the practice is in the life of the person. It’s in the artist’s life. Where is the practice? Again, that’s the point.

TK: Where is the practice? I do understand what you mean. I think that, also with social media, this idea of existing beyond the work has become important, almost essential, for so many artists. I like how this discourse challenges preconceived notions about what art is and isn’t. I think it broadens our reflections as we start to ask ourselves: where are the limits for art? But I have to say that my attachment to art-making is very important, even vital. I need to create things that exist outside of me, that can move beyond my own body and identity.

EM: Where is the limit? And where is the art situated?

TK: In the context of my own work, I have always had this need, an urge, to create in the physical world. I’m at once fascinated by new territories and forms of art where people are in doubt about what they’re looking at and experiencing, and I simultaneously have this radical need for physicality and to create things that exist beyond the screen.

EM: Of course, people need to experience the world and the self again beyond the screen. Fashion today seems to be looking into it right now — looking at physicality despite the recent blockchain trend. But I see that fashion is able to understand the art world in its physicality. I mean, it sees the potential in this sense. How do you feel about that?

TK: I think that fashion, because it’s so much faster than art, is somehow much more symptomatic. It has a capacity to quickly bring things to the surface because it moves so much faster. And at the same time, it is so obsessed with consumption, which also means that the things it produces evaporate almost as fast as they arrive.

EM: I think that your work with clothes is closer to the theater, and scenography.

TK: Yes, it probably is. I think that in the clothes I make for my performances, for example, there is this idea of going back to the beginning. The clothes are very archaic.

EM: We might say the primitive and primary shapes of fashion. This idea of stripping back and taking away and going back to essentiality in your work takes it out of this idea of fashion. Even when you created clothes for the performance The Ear That Hears Me (2021).

TK: Making garments for performances has always been important for me because there is no difference between clothes-making and sculpture-making. Both are three- dimensional and will move through space. I know how to make complex garments, but I much prefer going to the essential need. The same way I work in sculpture. The difference between art and fashion is, of course, context, but above all speed, rhythm, and temporality. We are on two different time levels.

EM: A different rhythm. Sometimes I think that fashion today is much more capable somehow of bringing to the surface things that art somehow doesn’t anymore. That it’s maybe more constructive somehow. Why can’t art do that anymore?

TK: I currently have this feeling that art is in cardiac arrest. And I think that it’s because art has been put in a position where so much control is far from the artists themselves. This loss has had a big effect on the ways in which art can be radical and reinvent itself. Art is now an industry where the actual making of art is most often governed by capitalism. Sorry, this is a very pessimistic way of looking at the current situation, but to bring new ideas forward we have to be able to detach ourselves from the systems that hold us back.

EM: Where are artists going? Where do they place their work? These questions have literally moved your practice since the beginning.

TK: For a long time my work was hard for people to accept because it didn’t fit into any mold. It was as if my work wasn’t supposed to look the way it does because I was a second-generation immigrant from the suburbs, dealing with questions like identity, migration, and loss through a highly abstract language. There is a lot of racism in the art world and many predefined roles and categories. I wanted to work against all of that. I still need to work against that.

EM: Your work is not explicitly about the history of being an Arabic immigrant raised in Europe, but more about the kinds of ambiguity

that this can generate. How is your work perceived in different countries?

TK: People weren’t ready for that ambiguity ten years ago. The question of the migrant is different everywhere. But my work never felt at home either in Europe or anywhere else. I didn’t flee the war from Palestine. My parents fled the war. I have grown up in a very different psychological and emotional reality from that of my parents. To be born with cultural and identarian amnesia in Europe isn’t easy. The core of my work stems from this. How you constantly move in that ambiguity, between different contexts. Between different languages, disciplines, and cultures.

EM: Do you think that today critical thinking can be reached through any of these domains?

TK: Critical thinking is just something that you have to apply. There are so many sources to look at to understand how contemporary culture is evolving, how things are changing and transforming. We have an obligation o look at things outside of art, like politics, ecology, fashion, theater, cinema, etc. For me the essential thing is less labeling and more thinking and questioning, if that makes sense. Where there is new thinking, there is always reason to look.

EM: And if I could ask: How do you define abstract shape?

TK: It’s internal. Abstraction happens on a very subconscious level. Sometimes the hand precedes the mind. Abstraction is beyond control. Its emergence is something that can’t be fully documented or explained. It moves on another level, far from knowledge and thought.

EM: It’s not about what a shape represents, but about where it comes from. How it emerges. It’s an ontological question.

TK: I believe that there are things deep inside of us that are far beyond our comprehension. Things that fall outside the idea of culture and knowledge. Things that might link us on a subconscious level. How it arrived is perhaps more important than what shape it has. Felix Gonzalez-Torres wrote, “We are not what we think we are, but rather a compilation of texts. A compilation of histories, past, present, and future, always, always shifting, adding, subtracting, gaining.” For me, the accumulation of layers gives birth to something that is beyond my own understanding. As references merge, the forms are born from within.

Sometimes I find there is less and less space for the subconscious. Today, many artists work as journalists and documentarians, investigating the wrongdoings of the real world. But where does that leave art? Is the artist to be the moral backbone of society? We all have that responsibility. I think, in this sense, it is necessary to remember that abstraction and imagination are also powerful roads to critical thinking and political discourse.

EM: Yes, but nowadays the attitude is completely opposite, because people need to show everything.

TK: Opposite. Exactly. But I also think that now, quite recently, people are in need of ambiguity, things that are not black or white. It is the result of a globalized world. I recently noticed that people are much more interested in listening to voices like mine. I move in a gray zone, and that is something that a lot of people, especially from my generation, can relate to.

EM: Today a kind of need to be figurative in sculpture is also really, really present.

TK: Yeah, it’s really present. I have to say, though, that I try to stay far away from what is made and presented in the now. It is the way I have always worked; this is the only way new things can be imagined. To work from the outside to change the inside. It is important to me to create works that are coded. I don’t want art to be easy. I work from myself outwards.

EM: Your “Vestibules” are metal strips and nothing more.

TK: I want to challenge people’s imagination. I think by that you also challenge people’s notions of what art is and can be. When you confront them with something that they don’t understand they want to know where it comes from. I feel like abstraction is above all a way of opening things up.

EM: And I think that today, this trend toward overproduction, to express the self in a very, very bulimic way, doesn’t help the art world.

TK: Yes. We’re producing too much stuff, and not just art. The self has become a highly exploitable entity in art. But what remains? Perhaps this links with the questions earlier, when we spoke of the work and the self and the existence of one perhaps without the other. I do sometimes think there is an unhealthy loss of control whereby thinking and art get lost in self-representation.

EM: Images today intoxicate everybody. And it’s really hard to create an image that stands out, because it all just ends up in this sea of images, and no one is thinking about what is an interesting image anymore.

TK: That’s very true. What is an interesting image? What makes an interesting image? Personally, I feel the need to retain things, keep them personal and speak when I really have something to say or share. I’m always thinking, “Producing less means producing more,” which is completely the opposite of what’s happening in the world today. There is, as you said, this bulimic urge to constantly share. As if selecting and reflecting was no longer possible. There is a middle ground here; I was never interested in the extremities.

EM: I don’t know when this system will really crash, but I feel that we are going to crash.

TK: For sure. Earlier, I said that I felt like art is no longer controlled by artists. When I was speaking of cardiac arrest, I was of course not speaking of production, but about the rhythm and pace that is needed to create and develop new ideas. I’m talking about the rhythm that is needed to move forward.