Andrea Bellini: When you curated the show “Superflat” at MOCA in Los Angeles, you wrote that the world in the future might be like Japan is today: super flat. Society, customs, art, culture: everything extremely two-dimensional. This seems like a scary world, because sometimes we have the feeling that the Japanese ‘super flat’ is a somewhat childish, dreamy, or puerile state of mind. What do you think about that?

Takashi Murakami: I think that you should be very scared then. But seriously, two-dimensionality is not a limiting factor. Just considering the arrangement of color fields on a surface, there are infinite possibilities. And there is a simple, important pleasure to be found there. In the end, I’m not sure that we want things to be as complicated as art commentators would like us to believe.

AB: A lot of Westerners wonder why so many Japanese artists are so comfortable expressing themselves with cartoon imagery. It could be a way to express discomfort, or to find refuge from reality, or to hide their imperfections behind a cute, always smiling cartoony surface. You have written several times that these psychological tendencies have deeply influenced Japanese culture as a whole. But exactly for this reason, ‘super flat’ could be just something ‘super easy’ for a Japanese artist to do!

TM: If you consider the amount of work that goes into most of the pieces, you would see that there is nothing super easy about it at all. But moving on to the cultural reading, I think that there must be a combination of a genuine connection and interest in cartoon forms, and an imposed self-consciousness of the cultural specificity of the form, that allows Japanese artists to embrace them so readily.

Chiara Leoni: How much of your inspiration comes from tradition (on the ears of Kaikai and Kiki for example we can read Japanese characters, and their names describe traditional qualities) rather than contemporary influences?

TM: I believe that the two are intrinsically intertwined. Whenever I see manga, I think of ukiyoe. Whenever I see Japanese businessmen, I think of Samurai. We are living in a timeless place, where nothing ever changes all that much.

AB: In Japan, after World War II, you had the Gutai movement. Gutai seemed more related to the Western idea of art: hierarchical and intellectual. These artists were not involved with Japanese popular culture the way Superflat now appears to be. What do you think about the Gutai and about the differences between the two movements?

TM: They had no reference point beyond contemporary Western art. The fact is that the Gutai movement was short-lived, barely known in the West, and when it was known, it was improperly interpreted and written about only in relation to Western movements. This is why, even if some interesting work was done by the members of this movement, in some ways it could be seen as a failure. In order to make a movement a success, it should be both somewhat self-sufficient, and also give birth to something new. It’s kind of the same as when people who can only compare themselves to others end up with no personality of their own.

CL: Let’s talk about your work. How do your characters come about? You seem to have moved away from the eroticized style of Miss Ko2, Hiropon and My Lonesome Cowboy towards the creation of characters that are related to the concept of kawaii (cuteness). How does a character come to life and how does it evolve? How does it enter and relate to the rest of the Murakami-world and to the other existing characters?

TM: How do babies survive? How do they convince their tired mothers to get out of bed at 3 in the morning and let them pull at their nipples? It’s because babies are cute. Scientific studies have pointed out that large heads and eyes, along with small noses and mouths, are a commonly found pattern of babies across several different species. I’m just appealing to the parenting instinct in my audience.

CL: Up to now, the otaku have exemplified a Japanese counterpart of the English ‘nerd.’ In your last show, “Little Boy,” they were interpreted as being politically charged, i.e., exemplifying figures of a passive revolt. How did you come to this conclusion?

TM: Yes, the otaku are a part of a great revolt against society, and in some ways, against reality. And similar to the English nerds, they are an ostracized group of society. Because of this, they have no choice but to be passive. It’s the same as when American nerds dress up in Star Wars outfits and wield light sabers. They are not really weapons. Society won’t let them have real power.

CL: You have said that your assistants usually do most of the required physical work. What is the pictorial and sculptural procedure behind one of your works? Do you prepare drawings or digital images for your paintings? And what about the sculptures? Are they digitally devised or do you have some hand-drawn sketches prior to their realization?

TM: Well, as I am not as young and strong as I used to be; it helps me when my staff can do some of the physical labor involved in making pieces. There’s so much hand control and minute detail work. I’d lose my eyesight! We do incorporate technology to generate drafts of works that use pre-existing computer elements, but for most new projects I always make sketches.

AB: What is Kaikai Kiki? Simply a good business for you and your affiliates or a philanthropic movement to help emerging Japanese artists? Or maybe both?

TM: I don’t think it could possibly be just one or the other. Also, I like to think of it as something much larger. A world-wide, 24-7 operational art revolution!

CL: You have claimed that the reason behind your founding of the factory, now a corporation, was to create artists. What do you mean by this and what is the purpose of such human manufacture? Do you want to create a school?

TM: Human manufacturing is not such a big deal. We all manufacture ourselves at some point in our life. However, I have seen too many talented individuals fail in their endeavors because of poor management and lack of know-how. I want, quite simply, to help artists advance in their careers. In some ways, Kaikai Kiki sometimes feels like a school with me as the principal (maybe because all my employees are young?); but it’s a special school with special goals. I am not very interested in conservative school structures.

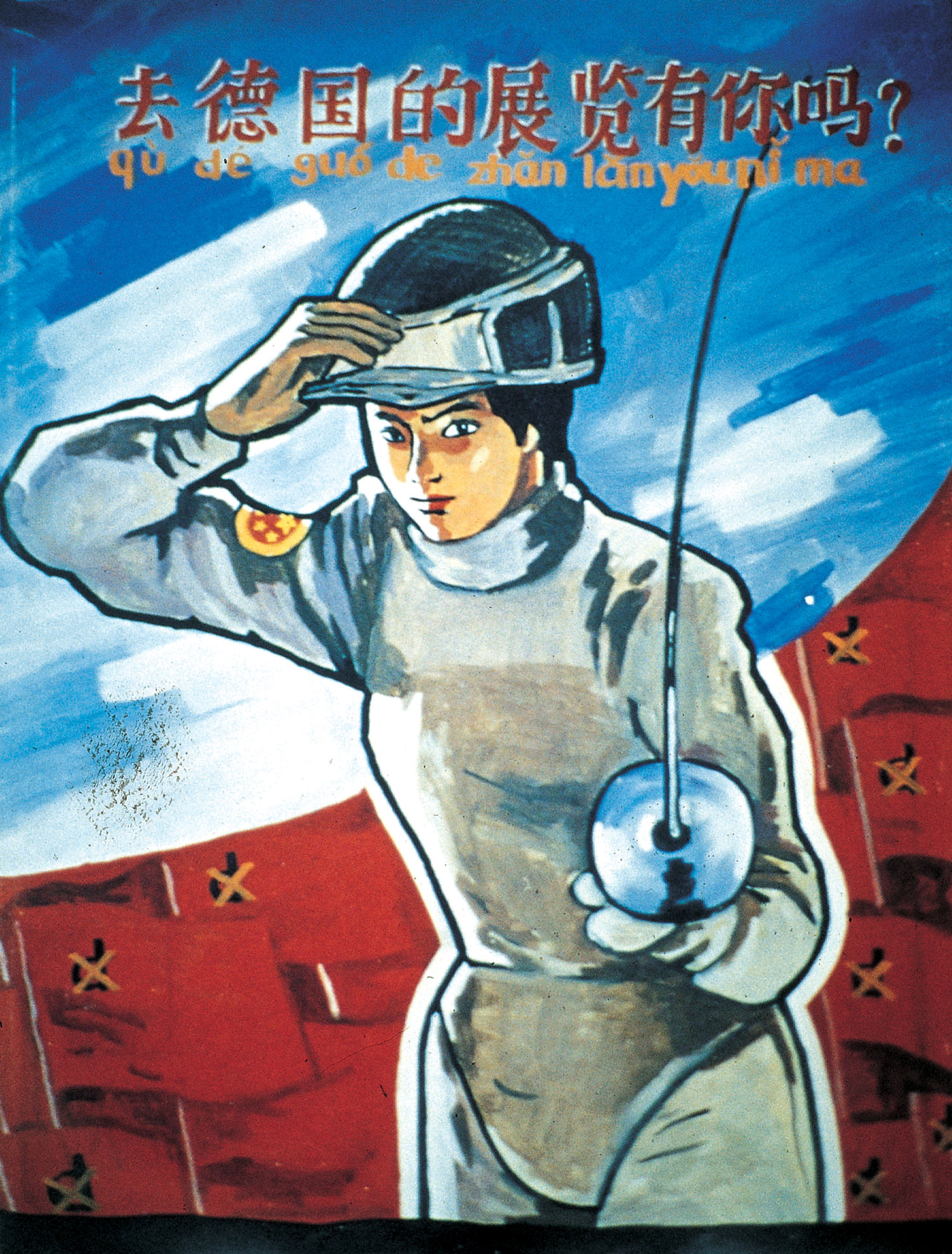

AB: Geisai is the Art Festival you have launched in Japan. What kind of art fair is this? Is it dedicated only to young Japanese art?

TM: I wanted to create a movement in Japan in a new direction. I have become frustrated at the current situation of the art world in Japan, and realized that if I were to make a splash, it could be any kind of splash that I wanted. It also so happens that as ‘contemporary art’ hasn’t been ingrained in the general Japanese populace, it was easy to make it a sort of sceny, fun, hip fair for younger people. There is a lot of creativity among Japanese youth, and I was happy to tap into that. In terms of the physical manifestation, I had garnered some funds and some connections. It really wasn’t that big to begin with; like any seed, it is planted small, and let’s hope that it grows strong and tall!

CL: You are renown for being over-zealous. Could you describe your daily life?

TM: I wake up very early. I am a morning-person, so sometimes I am irritated with my Japanese staff when they arrive groggy from their long commutes. These days, I have video conferences with my New York employees, who are finishing up their day. I guess you could say I keep myself busy.

CL: What is eccentricity according to you?

TM: Everything could seem eccentric through another value system.

AB: Who is Takashi Murakami?

TM: Give him some rice to eat, a tatami mat to sit on, a high-speed Internet connection, and he’ll be happy.