Every time I meet with T.V. Santhosh, I cannot help but wonder how a person with such a soft-spoken and quiet disposition creates artworks that are so visually bright and conceptually powerful. He always greets me with a mischievous grin, and we talk about everything but art. Over the years, I have observed that his paintings have become his voice. The “solarized negative” palette he realized a few years ago, with burning yellow, red and orange contrasted with greens and blues, has become internationally recognized as his unique style. His subject matter heightens these hues with controversial images of prevailing social, political and religious unrest in India and around the world. Men at war, women praying in burkas — T.V. Santhosh captures frozen moments of struggle and injustice. Most of the images he portrays are inspired by news and television. His interpretation of the media — and its reception — is part of an evolving practice that questions the “system” and exploitations of power.

Kanchi Mehta: Cinema strongly influences your practice. Which filmmakers had an impact on you?

T.V. Santhosh: There are many films and directors I admire. There are many indirect influences, rather than direct ones. Watching movies helps me to understand the language of cinema, as well the philosophy of art. There are several genres of film, literature and art, and there are very distinct approaches to them. Especially in the case of cinema, because of the power of the medium and the kind of strong influence it can have on society at large, like Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925). Although it was considered propaganda, it was a powerful movie that directly reflected on society back then. Here, cinema is used as a tool of resistance, instrumental in motivating social change. Ingmar Bergman and Andrei Tarkovsky also formulated their own distinct language, altering our perceptions of cinema. While Bergman was existential in his approach, Tarkovsky was more spiritual in nature. In films like The Mirror (1975), Andrei Rublev (1966) and Stalker (1979), the language and understanding of the medium is so refined that you cannot separate the technical, linguistic, visual and conceptual elements from each other. This kind of filmmaking is what I would have liked to produce. Metabolism Test (2003), one of my paintings, is the central image of Bergman’s movie The Seventh Seal (1957). In his films he asked many questions that were relevant then, and are even relevant now, such as, “What is the relationship between religion and society?” or “What is the role of war in shaping the human victory?” Filmmakers like Mohsen Makhmalbaf and Majid Majidi have made wonderful movies about religion and society in Iran. It is sad that one of the most interesting and influential filmmakers, Jafar Panahi, cannot make any movies after being banned, but he will be back. Kim Ki-duk, Andrei Zvyagintsev and György Pálfi are also making interesting movies.

KM: What is your philosophical approach to your work, and how is it different from the way you look at your life?

TVS: My work is not intentionally political. It is an investigation about the angst and despair that continues to persist. Almost like a “butterfly effect,” which signifies one small incident that eventually turns out to be a larger catastrophe. Like an endless cycle of revenge, where religion, power, knowledge and hatred is involved. Although I am not religious in a conventional way, I am interested in some kind of mystical energy. I don’t think that one must succumb to the accepted notions of its conventions or exploit it for power. I look at religion in a more humanistic way — and my life in an eclectic way. I still believe in the relevance of Marxism, its pure intentions where equality and human rights become essential components of society. In order to understand the language and elements in my work, one has to apply the same worldview. I don’t limit myself to a rigid framework of understanding, and therefore my work keeps changing every few years.

KM: Your subject is relevant to the past, the present and the future. How does your work fit into a global platform with reference to philosophy and ideology? And what is the relevance of the color palette to your subject?

TVS: Initially, my work was more monochromatic. The gradual transition to bright colors is merely an extension of what I was doing before, or rather, it is an area that I could not explore in my previous phase. My monochromatic works were almost like looking at historic pages, trying to find the implications of violence and war. War and terrorist activities can be viewed at many levels. One man’s hero is another’s enemy. When I depict something that happened in history, I connect it to what is happening now. There was a period between the monochrome and color works when a crucial shift occurred with the use of the photographic negative. It made me realize the possibility of juxtaposing the positive and the negative. Hence I did not see a need for the diptych: I merged the elements of positive and negative in one canvas. It is like looking at the same issue, differently. How the media projects reality is an integral part of my work. My linguistic and philosophic aspects are inseparably intertwined with the possibility of exploring the local and the global through photographic negatives. Local elements like faces become obscure in a negative. Hidden implications are encoded within the negative. And if you make it positive, it is automatically decoded. Fear, Nation and False Promises (2004), a title of one painting, can connect us with historical, social and political references. Although the original image comes from the Iraq War, it could be anywhere. False promises are made; truth is manipulated and nationhood is questioned. And the idea of animosity is manipulated by the system as propaganda.

KM: Do you struggle in order to sustain your position in the global arena?

TVS: The struggle is constant, and every sensible artist has to go through it. As a person I don’t look for recognition from outside. My work is a confrontation towards my understanding within. People have two identities. One is constantly changing, and one is changeless. We must confront both at the same time and believe that there is something changeless in you, even though the world around you is constantly changing. This balance must be maintained, otherwise it becomes very difficult to survive in this competitive and fast-paced environment where saturation and stagnation are professional hazards. When I feel either of the two, I stop working for some time.

KM: Over the years, your work has reflected very subtle changes visually, primarily because these changes complemented the ideology of your work. What is your opinion about shifting artistic practices by an artist over the span of his career?

TVS: As an artist, it is very important to reinterpret yourself. Stagnation can kill an artist. Alvin Toffler’s book Future Shock (1970) analyzes the time history has taken to move to the next phase within different fields of science, culture, politics, etc. There is a pattern of parallels emerging at the high points of each shift. Initially, every field has taken centuries to move to the next level. Art was the same. With every movement, like the Renaissance, the High Renaissance, the Baroque era, Impressionism, each style has taken a hundred or more years to sustain, evolve and graduate into another style. Within each, there have been many smaller points represented by subtle changes, but the basic ideology remains the same. Today there are many movements prevailing at the same time. And, like the process of fragmentation, they are becoming more complex. An immediate change is expected, and the time between two high points has been reduced. With art today, it is the same. Which is why we get dissatisfied very quickly with an artist working in the same style for a long time. If an artist is satisfied with his progress, however slow it is, we must respect the rhythm. The profit-oriented ideology of the neo-imperialist and capitalist outlook has influenced us. Before, many galleries disapproved of changes in artistic practices with style and medium, but now they have adapted to it. In India, galleries are slowly opening up to challenging art and encouraging artists to innovate their visual strategies. Young artists may not be comfortable handling new media but follow it merely because it is the trend. The “notional” pressure to be a rebel and the psychology of the viewer’s fast-changing approach to art creates a vicious circle. Extreme individualism is the product of modernity, and the fragmentation of the social fabric further creates a divide. It has become almost like a natural process that we are a part of, consciously or unconsciously.

KM: How do you perceive this generation of artists, their conceptual works and new media?

TVS: Conceptual or new media art is merely derivative of what has already been originated. If you are thinking in the logic of language, then it is merely a reinterpretation of what someone who was not necessarily an artist conceived, now being adapted to new methods and media. The younger generation is always attracted to new trends; it is natural for them to break away from conventions. We must be aware of the dynamics of the art market, which are very complex and powerful. Like many rebels in history who later became part of the system, many anti-gallery, anti-market art movements have been absorbed into the same system. An artist is appreciated only if his work reflects his true potential. Not because the audience expects it. Personally I am not interested in the idea of a change forced from outside, but rather a change that is an inner necessity.

KM: Which contemporary artists from India do you admire? And internationally?

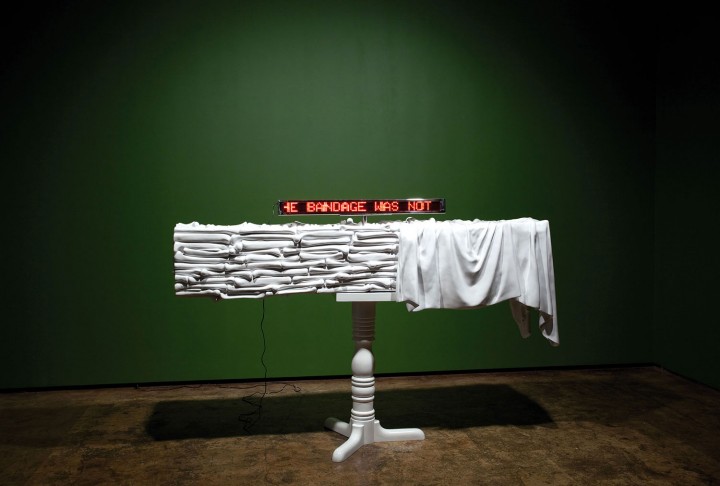

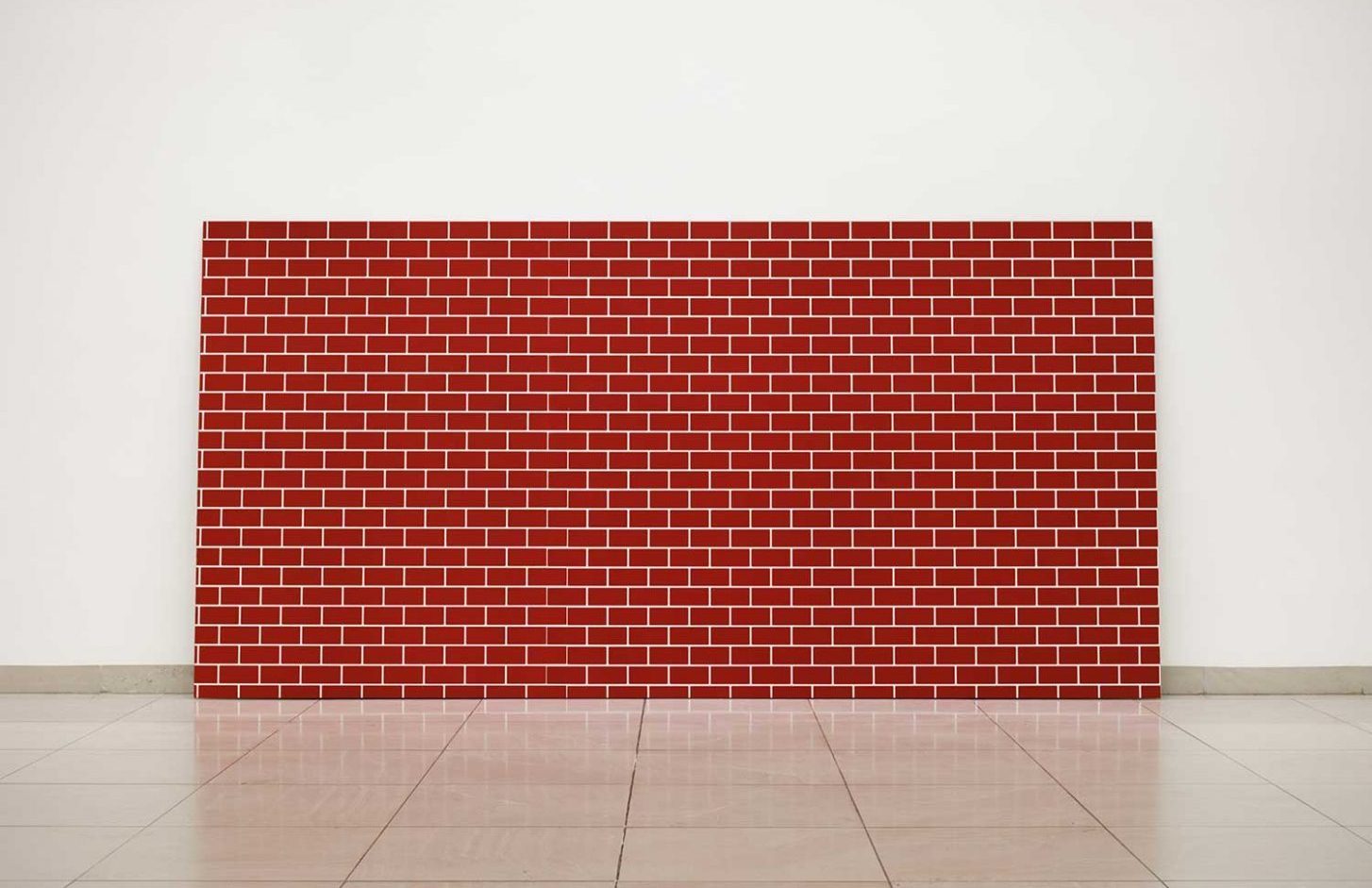

TVS: In India, I like the practices of Sudarshan Shetty, Atul Dodiya, Riyas Komu, Subodh Gupta and Baiju Parthan — and there are many more. From among international artists, I like Maurizio Cattelan, Neo Rauch, Christian Boltanski, David Salle, Jeff Koons and Wim Delvoye.

KM: If you weren’t an artist, what would you have been?

TVS: I would have loved to be a filmmaker, and yet that comes under the category of being an artist. If I had not been an artist, then I would have been possibly a monk. Not a monk who renounced the material world, but one who lives in this world, with the energy to change it. There are many ways of looking at monkhood. There are people who abandon the daily, mundane life, and also there are people who come back into this same world with a different purpose, like Buddha. I would have liked to be the latter. Like the term “Paramahamsa,” meaning the Supreme Swan, which even after emerging from dirty and muddy waters is yet pristine and white with their feathers untouched, which is the quality of a self-realized master who can separate the truth from delusion.