Since his first public solo outings about three years ago, Sterling Ruby’s combinations of performance-video, occultish drawings and collages, organic polyform ceramics and stalagmite sculptures have plumbed the dynamics of individual desire within societal constraints. Granted, it’s familiar enough territory; any adolescent grounded on a Saturday night could probably give you an earful. But in Ruby’s hands, an erotic frisson of betrayal and border-crossings (think the Genet side of Derrida’s “Glas”) is coupled with the idea of a subject with no subjectivity other than the need to resist, a catch-all anarchist who delights in trespassing just about any cultural precedent or mandate.

One series of Ruby’s works is entitled “Supermax,” a take-off on the subject of repression and control in the maximum-security penitentiaries of the same name. As fans of the TV series “Lock-Up,” Friday night’s bit of muscle-porn on MSNBC will know, a Supermax is the new breed of mega-jail. In these institutions reform takes a backseat to mere detainment and a “do the time” worldview of innate criminality is embedded architecturally.

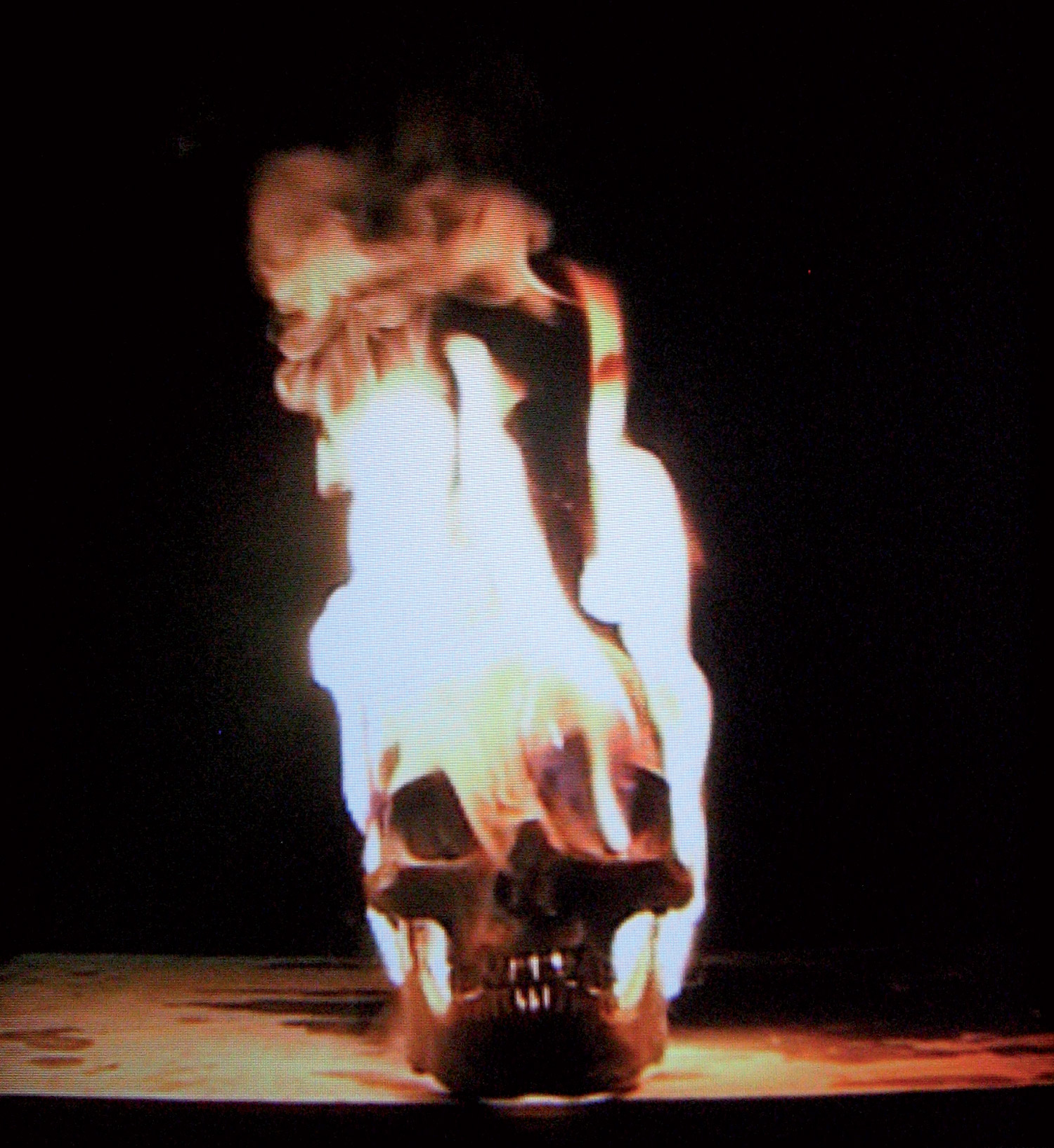

Ruby’s version of the new Alcatraz, played out through several sculptures and collage configurations, attempts to perform the plight of the purportedly unreformable as a stand-off between the tyranny of fascistic architecture and its “hardened career criminal” subjects. One work in particular, the freestanding Supermax Wall (2006), serves as the surveillance booth and less-than-conjugal visitor’s center for the series. Four panels of loogy-proof plexi-windows record crudely incised tags, vain attempts at bore-holes, greasy smudges, spatters, smears, scummy wipe-marks and cumshot drip-and-slides, capturing emanations which, though intended for visiting civvies on the other side of the glass, catch and suspend discharges onto the transparent walls of the institution, lubricating, desecrating, obscuring, and in the end reinforcing the barrier between outside and in. Whoever’s imprisoned behind this forced-field obviously wants out but simultaneously writes (or marks, scratches, spits or cums) himself back in. The institution, its architecture and its monumentality are not only the receptacles of these signs of resistance but, ultimately, their own agitators and cause.

On one hand this is not resistance at all but, rather, a strong dose of cabin fever, the irony of which may be most evident in Ruby’s video portrayals of stir-crazy loners. In Agoraphobic (2001), for example, a disenfranchised ‘go-fer’ opts out of the corporate ladder by stripping down and burrowing a paralogical ascent through an office building’s airshaft; but the little bit of fresh air he gradually finds, a mountain retreat custom-fit for a Unabomber, is just as cruel and overwhelming as the middleclass oppression he beats a retreat from. Similar dynamics of low-level anarchistic trans states occur in Transient Trilogy (2005) where a transvestite transient, making the most of the adage “one man’s trash is another man’s treasure,” pollutes at the same time as s/he makes her/himself at home; cross-dressing and transgressing property lines and taboos describe a subjectivity founded on the thrill of crossing for crossing’s sake.

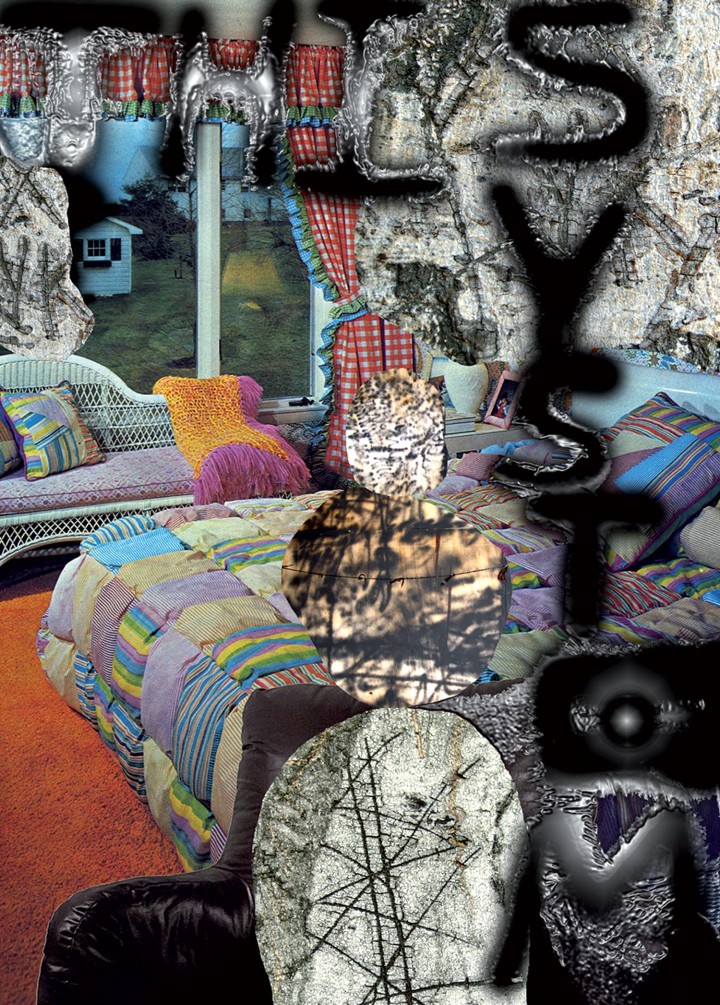

The most recent works, “Physicalism the Recombine,” focus on yet another kind of crossing, transfiguration by way of bodybuilding. By collaging images of homemade candles with the slick-shaved and striated grotesqueries of muscle competition photos, Ruby points to gender slippages in self-improvement culture: men sprout boobs and women tend to show all the bulging veins and red-faced aggression one usually associates with wearing wifebeaters. But while playing on caricatured ideas of gender, the unlikely pairing of waxen handicraft globs and twisted steroidosauruses is also related to Ruby’s work in ceramics, specifically to ideas associated with less-than-high-art craft. In Ceramic / Two Stratagem Peace Heads, (2005) and Ceramic (Yellow, Beige, Blue, Black, facial) (2005) for example, both rather looking like clunky clay versions of god’s eyes and ghostcatchers (the ‘spiritualism’ to the other work’s Physicalism), issues of labor and transcendence — the common link between pot-throwing, basketweaving, macramé, candlemaking and feel-the-burn powerlifting — combine to propose that other alternative to oppressive controlling forces: therapy.

Ruby’s ceramics are also evidence of a certain antipathy towards austerity that is consistent throughout his work. The ceramics’ modest scale, handcrafted gloopiness and earthy materials serve as contrasts to the outsized scale and machine-tooled industrial materials of, specifically, Minimalism and continue lines of inquiry from such predecessors as Acconci, Hesse, Nauman and Schneeman. Whether in homely little rainbow-flagged ceramics, in the shat-upon gestalt of Monument Stalagmite or in works like Inscribed Monolith 1, a vaguely flesh-colored, cellmate-proportioned and rather hump-able plinth from the “Supermax” series, the message seems to be that the reduced form and self-evident structure of Minimalism, along with monuments, prisons, corporations, cultural mandates of gender and lifestyle or, frankly, any force likely to send a contemporary subject either running to the hills or into therapy, are just simply alternate versions of the same opaque forms of control and oppression.

Yet another option is proposed in a suite of Ruby’s prints entitled “Anti-Poster,” three Situationist-informed placards, one of which proclaims: “Finish architecture / Kill Minimalism / Long live the amorphous law.”