Olivia Erlanger: I’ve been really interested in the psychology of interiors and the way that space can act as a reflection of the mind. And I think that that really resonates with this idea of storytelling that you write about, that infrastructure has narrative capability. How do you see spaces, cities, towns telling stories, and what is an overarching narrative of infrastructure in a suburban space? To me, one would be the myth of the nuclear family as ultimately a narrative or story that infrastructure is selling us.

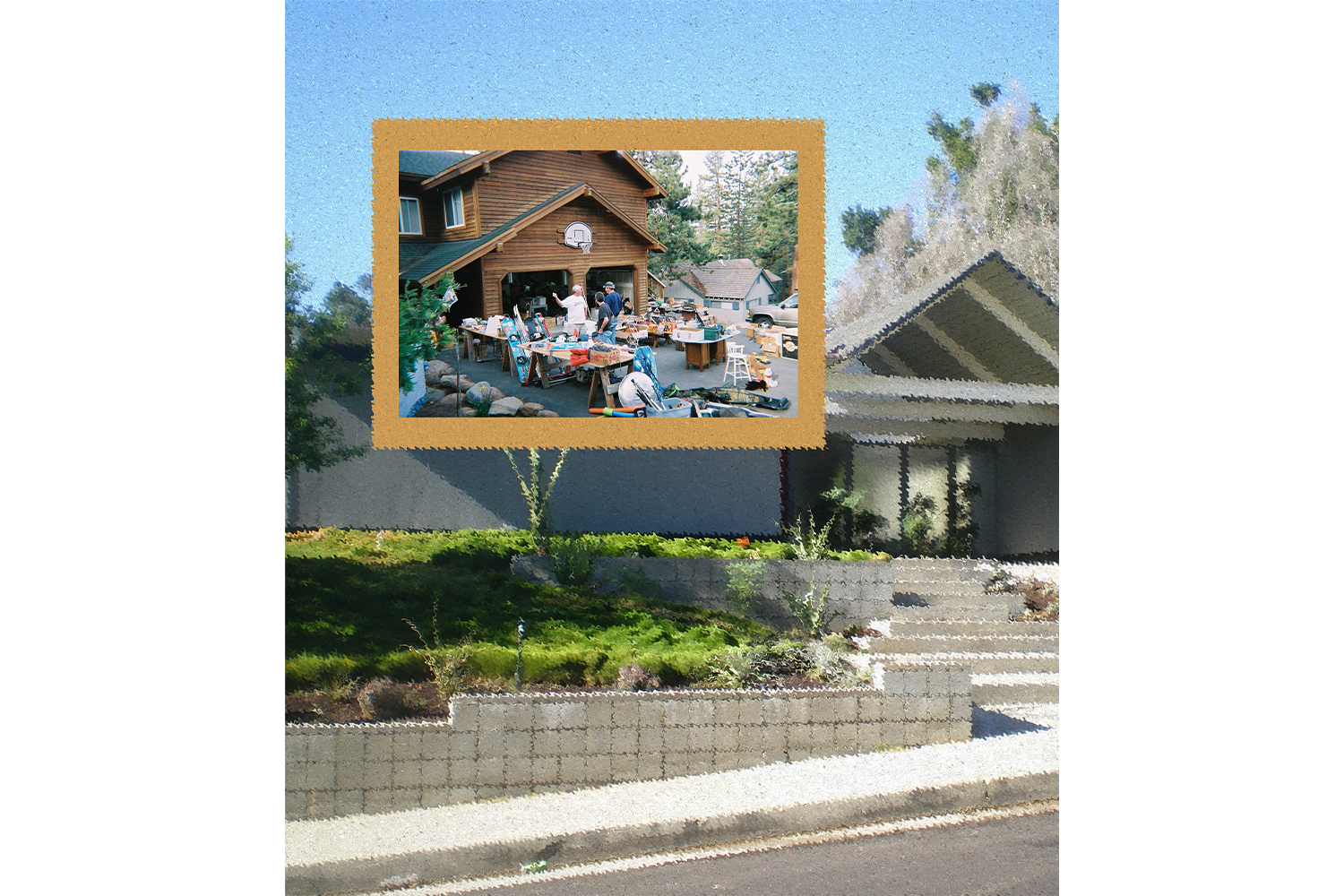

Keller Easterling: Within the repeatable suburbs of the mid-twentieth century, one of the narratives was about family. The nuclear family was also associated with patriotism — as if you were carrying on the war effort by building a house and taking part in the transition of wartime industries into the housing industry. As the century goes on, other narratives about exclusion and luxury offer an amnesic sense that what you’re buying is greater freedom or autonomy. There is also still some lingering idea that you’re in the country or something like that. But the unspoken disposition embedded in the arrangement of the house is the most consequential. It makes some things possible and some things impossible. The house is constructed as a hybrid between the assembly line and the agricultural field. And the houses were financial instruments that were part of a scheme to jumpstart the economy.

OE: Right, building houses was never the real point. The point was to make mortgages, to make capital. The home is just an instrument of currency.

KE: Exactly. The idea was to make the houses bankable, or like currency. The Federal House Administration approved houses that were self-similar, and they rubber-stamped large batches of similar houses. The houses were part of repeatable formula or spatial product. It’s not as if you bought a lot and decided to build a house that was suited to something you wanted. Houses could not have a flat roof, for instance, because this was seen as too eccentric. Because of their position relative to the city, the houses all had a garage—an attached ten-by-twenty- or twenty-by-twenty-foot box. And traffic engineering geometries like turning radii formatted OE the world. Beyond morphology, the FHA also develop procedures, as you know, that excluded people of color.

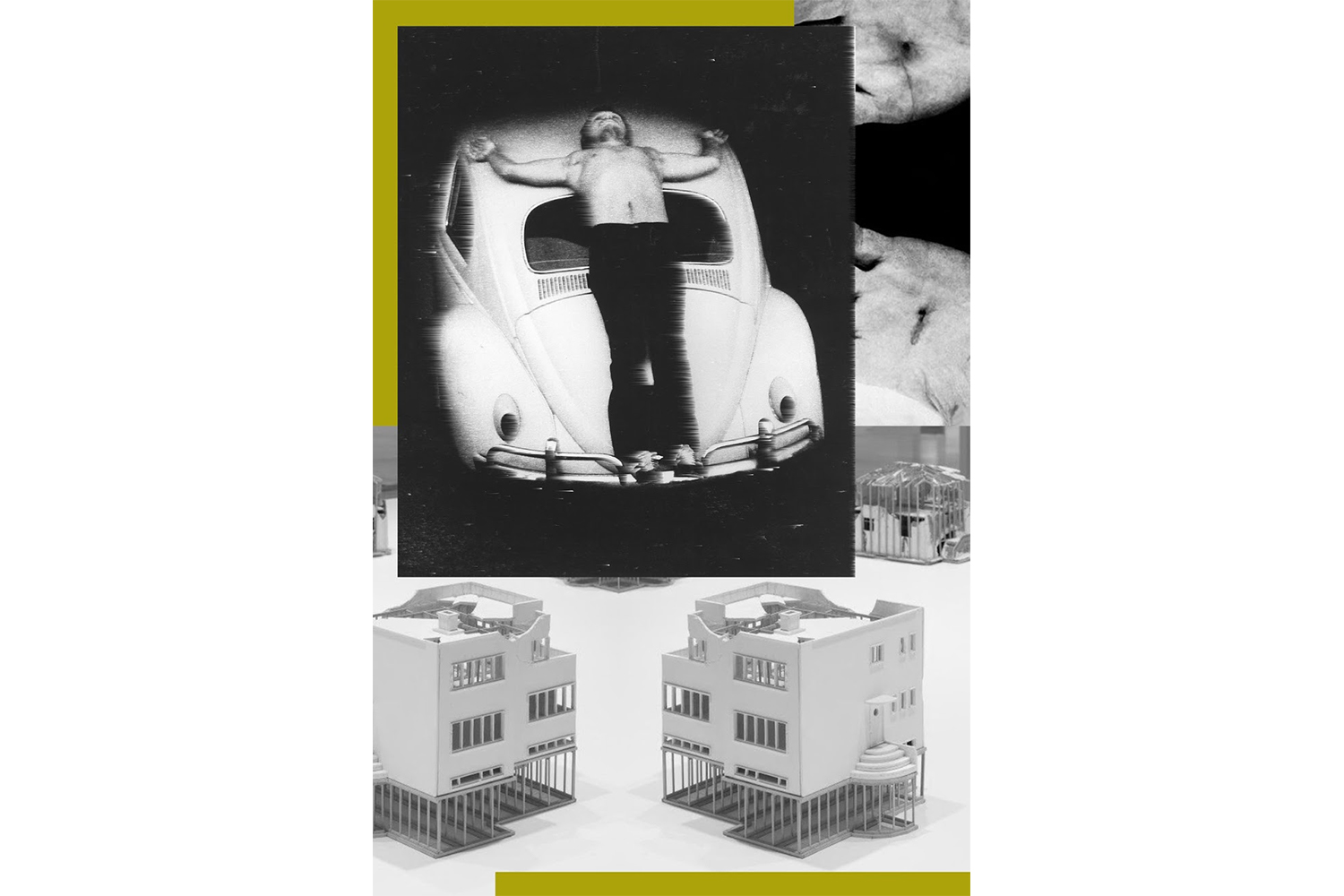

OE: It’s as if those houses, at least as Luis Ortega Govela and I were looking at it for our book Garage (2018), are built and designed for the machine rather than for the human. And this sort of mechanization of domesticity is then exported. And one thing that kept coming up as I was reading Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space (2014) is just how global your perspective is, that your references are not limited to just Western typologies or ideologies. And I wonder, do you think the Fordist line of production changed this or instigated this American production of suburban spaces with houses all alike, and then that got exported culturally through cultural imperialism on a global scale, and you see these sort of Western-style suburban enclaves in parts of China, etcetera. What technology or what political change or technology do you think that’s a reflection of? How do we end up with a global idea of suburbia such that lives may be less in a physical space but rather in a shared collective imagination?

KE: Well, in a book called Organization Space: Landscapes, Highways, and Houses in America (1999) I was trying think about the way in which the mid-twentieth-century US suburb was a spatial product. This field of houses so clearly modeled the idea. But heir to the “org man” that Harold Rosenberg identified was, it seemed, another kind of organization man making spatial products of all sorts — repeatable formulas for suburbs, container ports, agropoles, resorts, cruise ships, or skyscrapers.

OE: Seriality en masse.

KE: Yeah. And the org men are shaping both space and time. So a big box is not really a building. It’s more like a kind of assembly of protocols for stock-keeping units and parking and just-in-time production and so on. There is an enclosure but the logistical interplay is the real intellectual property. Or back to houses: the golf course community is a contagious spatial product around the world. The formula involves subdividing the surface area of the golf course with enough villas to match the debt incurred in building the fairways. It is a game played by men and women in the afternoon, but it’s also a game of number crunching played by developers. And the accompanying narratives are varied. In China, for instance, the story may be about having arrived at another kind of status or rank within an increasingly capitalized culture.

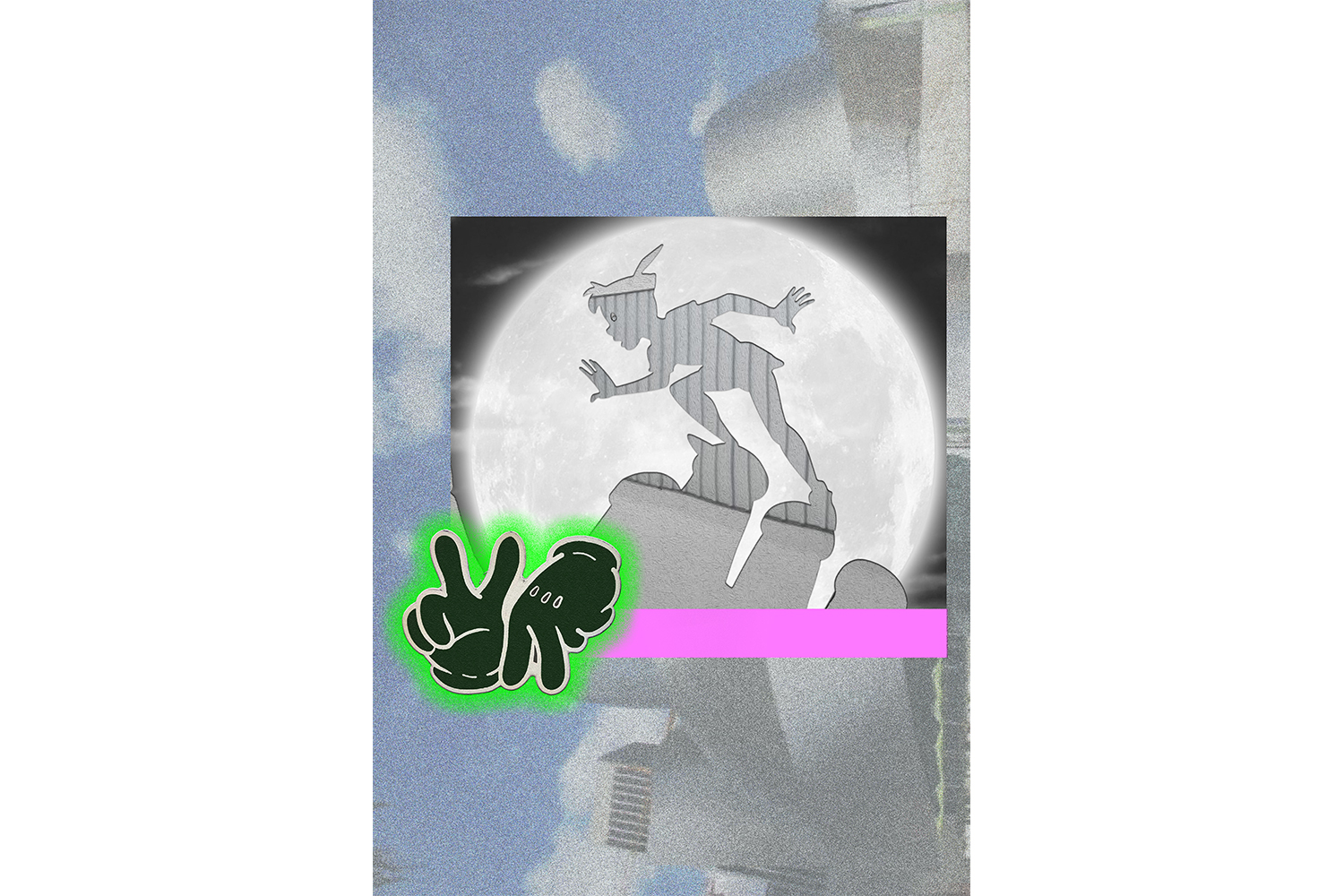

OE: These communities sell and prey upon a larger narrative of aspiration, one that seems to be totally entrenched in an American ideal. It’s interesting to think about how capital “performs” and in particular how it performs in structural decisions. I wonder how your own experience in theater informs the ways in which you understand spatial intelligence, performance, and potentialities for space to enact upon users, offering new entanglements? I feel at least that space and the objects contained within almost have panpsychic qualities. Personally, I wonder how infrastructure decisions affect the construction of identity and the performance of self. Or if it’s the inverse, if constructing one’s disposition is a reflection of these invisible forces.

KE: Infrastructure is used broadly sometimes to refer to the pipes and wires of transportation, communication, or utilities. What I’m really trying to describe is another sort of matrix of a much broader apparatus that’s not always hidden, as we usually think of infrastructure. It is the stuff we’re swimming in, all the rules and relationships that format the spaces that we’re moving through. Institutions that are reconsidering their “infrastructure” are maybe reconsidering their constitution or disposition—how their arrangement makes some things possible and some things impossible, or how their internal arrangements might have a different chemistry. It is this focus on the disposition of a matrix and space that I’ve been trying to articulate.

OE: In my understanding, what you’re describing is a meta-modernist perspective of the through lines connecting self, location, and experience to history. Or it’s really an attempt to begin to pull back, zoom out of the matrix of the legislature, built environment, community that’s side by side with our feeling of what constitutes “reality.” This really resonates with how I think an artist’s brain works, plumbing the depths of the spaces between language and construct, between form and material.

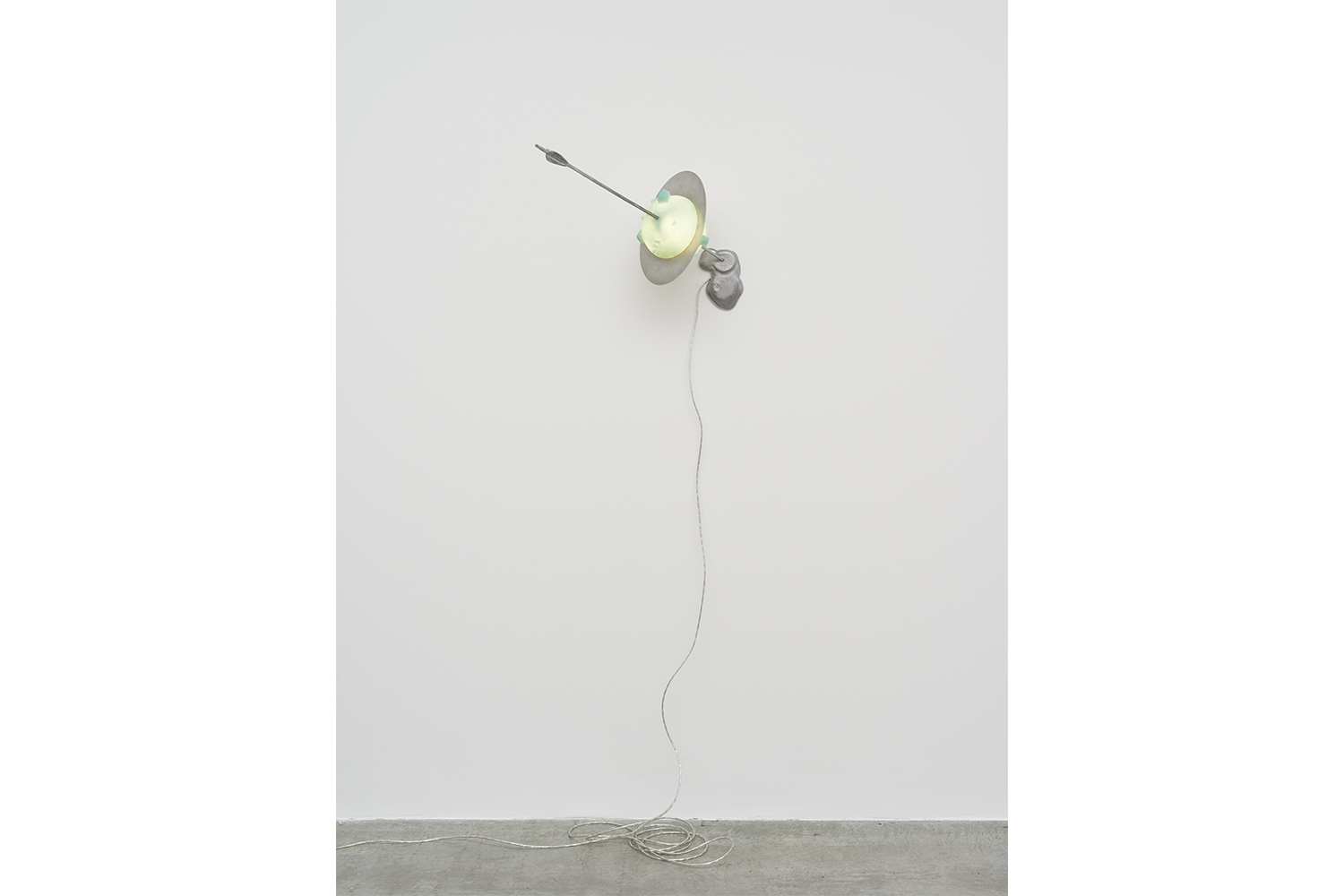

KE: Maybe there is also a critical exposure of the modern apparatus. Thinking in this way, not about the objects but about what’s between the objects, is non-modern. It’s a way of exposing the modern Enlightenment apparatus that favors declaration and object and lexical expression and so on. I always say that I am trying to look with half-closed eyes past objects and to see relationships between things for relational intelligence. I am suggesting that thinking dispositionally is one way to see past those stubborn habits of mind—past homo economicus and geometrized property and solutions and on and on.

OE: This makes me think of your book Medium Design: Knowing How to Work on the World (2021), which uses the identifier of the designer rather than the architect. It’s interesting, as what you’re describing as the way in which a designer sees is actually a way of looking at or examining the space between two objects. Yet this is fundamentally how I think of art-making. As like a space between languages. Artists — or at least my way of thinking about what I do — try to delve into the in-between: a visual language, a spoken language, the built environment, and the sense of the ephemeral. All of these different kinds of vernacular. I don’t personally see much difference between the roles of architect or artist. In many ways, it’s all similar in terms of strategies, problem solving, or puzzle making. And I feel within the schema you propose in your writing that all of these modalities are actually just a way to describe similar patterns of thought. Ways of being and making that unite all of these roles, which I really appreciate.

KE: Medium Design was written to a broader audience to make a case for spatial practices and spatial thinking within a culture that gives more authority to anointed digital, legal, or econometric expression. It focuses on the heavy, lumpy, physical information in space that should be consequential in global decision-making. It’s a practical thing that everyone’s doing all the time, but it’s under-expressed — to think ecologically, relationally, to think in terms of the interplay of things. But to the degree that everyone manages potentials in their environment, everybody is a designer. The subtitle, Knowing How to Work on the World, is not authoritative. It’s not solutionist. It’s the exact opposite of that. The book talks a lot about knowing the difference between knowing how and knowing that. “Knowing that” is something like knowing the answer. “Knowing how” is more like knowing how to work on something that doesn’t have any solutions, that unfolds over time and needs constant tending—like most things.

OE: Right. It offers an organic investigation rather than an empirical quest for an ending fact. It’s the difference between, I don’t know, being on a journey and taking a trip where there’s an endpoint.

KE: There are no singular solutions or singular enemies. It’s worse than that. Seeing in this way can also reveal more injustices and forms of environmental violence that may be accomplished not with a gunshot but with fossil fuels, sheltered wealth, monopolies of data, or murderous policing. And the community we were discussing—the interplay between human and nonhuman beings and objects can’t be quantified. This is just one of the ways that capital is stupid. Organizations that are alive can have incalculable productivity. If you plant one seed or one tube you get ten. Often it is a matter of getting the abstract financial apparatus out of the way of this excessive productivity. That is some small part of what Medium Design is trying to think through. But it’s a quiet contemplation.

OE: Oh, I think that’s a beautiful sentiment to end on.