A recurring refrain in recent decades is that painting is dead. And yet, it continues —sometimes loudly, sometimes zombified. “Painting After Painting,” a major group exhibition of seventy-four artists working in Belgium, doesn’t so much refute that claim as sidestep it. Rather than presenting painting as a fixed or unified discipline, the show casts it as an adaptable, restless form, constantly shaped by the forces acting upon it: history, capital, digital saturation, bodily autonomy, and the Post-Internet condition.

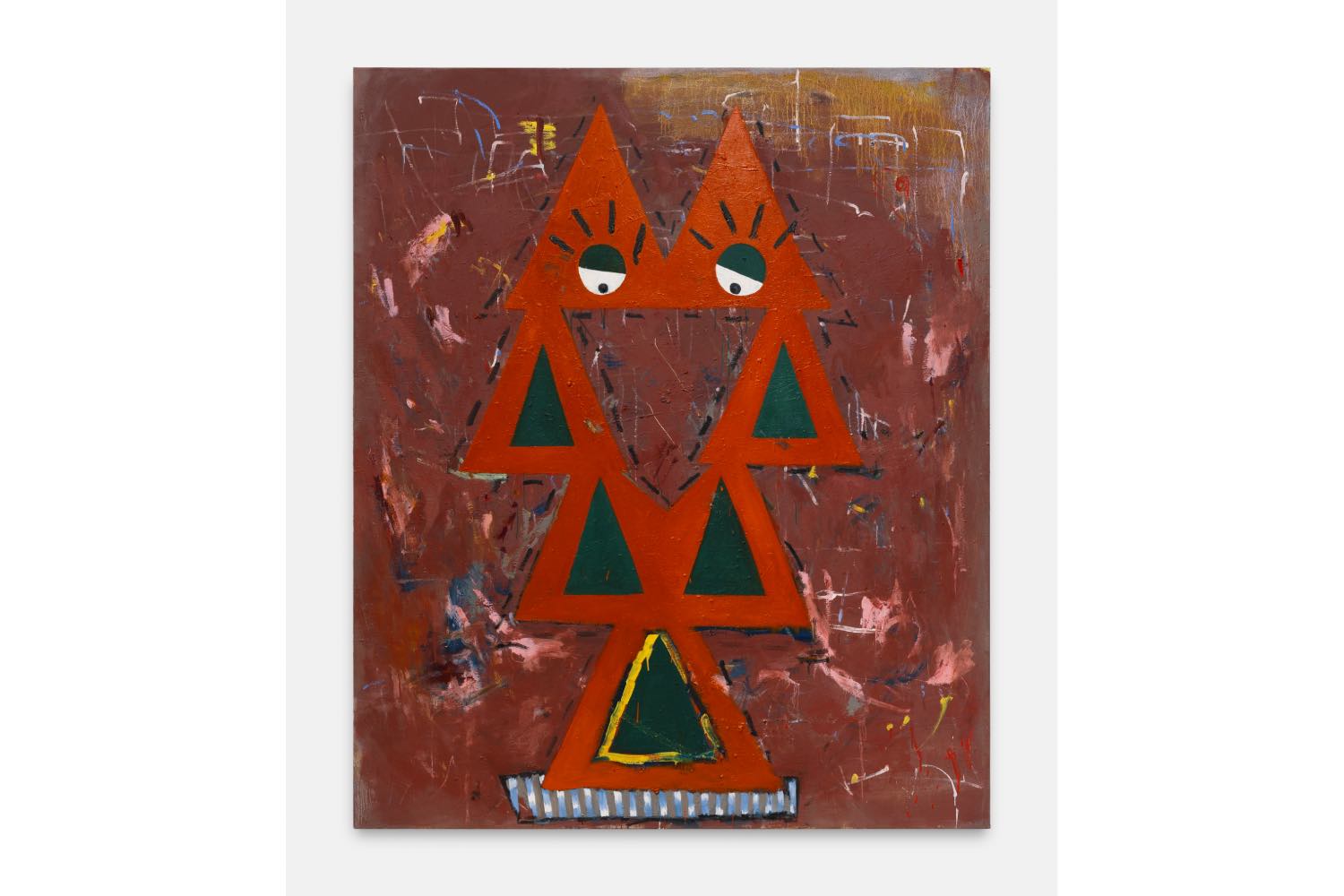

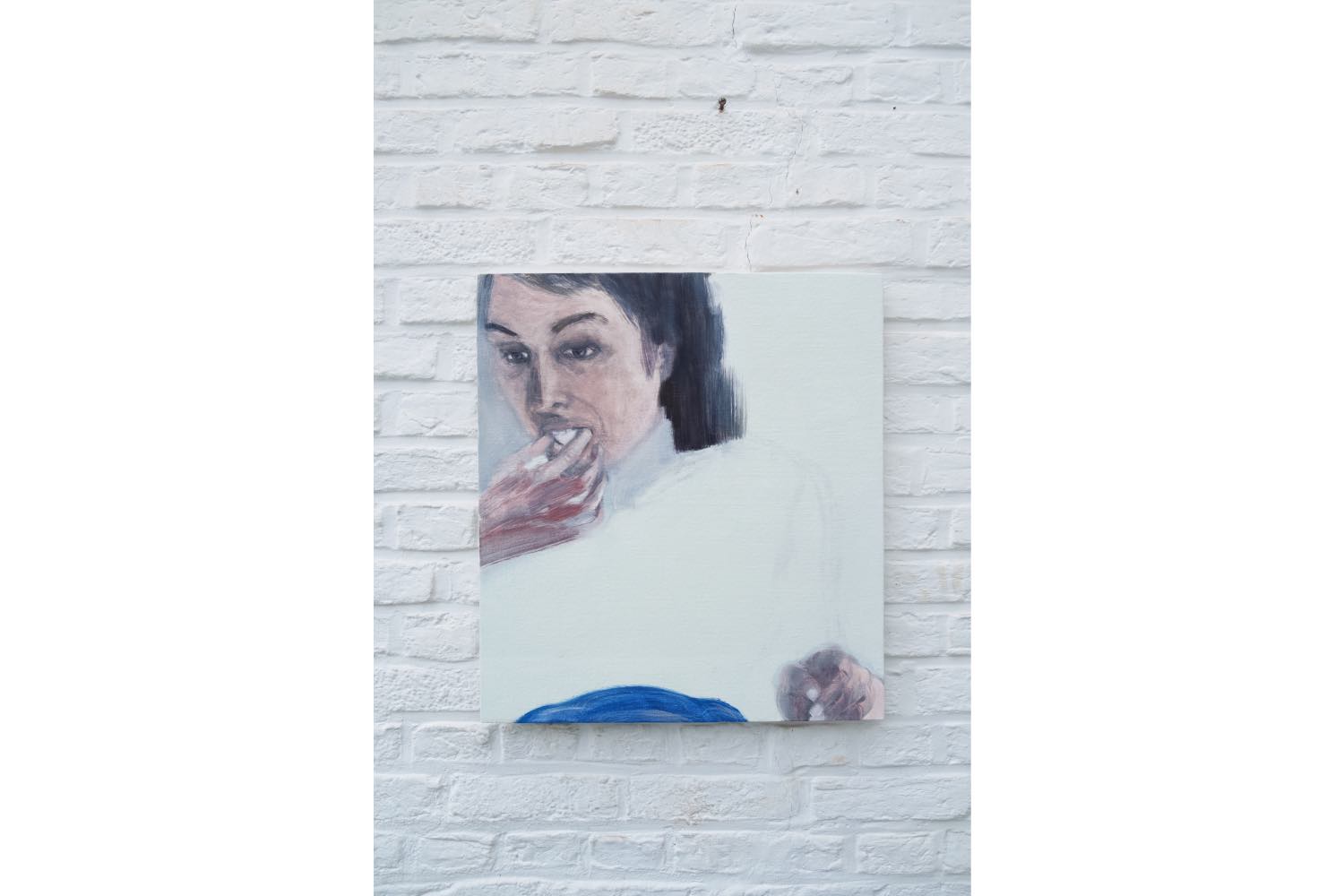

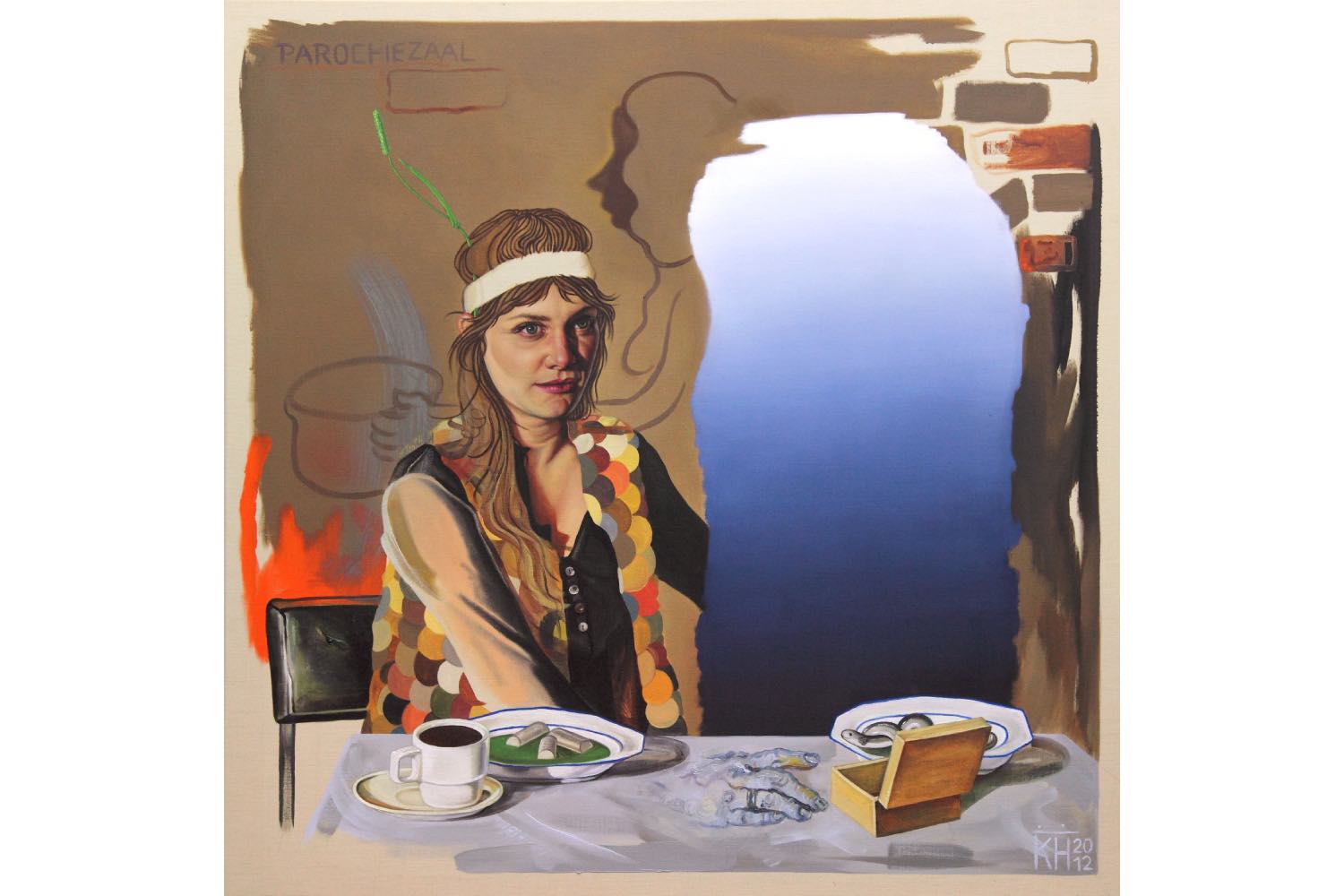

The show contains various loose thematic groupings such as “Intimate Worlds” and “The Fluid Body,” among others, creating space for varied approaches. Nina Gross’s Muckbang and Self-Portrait Eating (both 2024) channel digital voyeurism and bodily consumption through restraint. Her nearly minimal seductive surfaces ooze with anxiety. Bendt Eyckermans’s work brings cinematic unease to painterly realism. In Transition (Fade-In) (2023), a figure hovers midair while a looping vacuum cable cuts diagonally across the canvas. Ghostly traces of previous layers persist beneath, lending the painting a haunted quality, like an unresolved shot from a David Lynch film. Frederik Lizen’s Jean ai assez (2020) sets the tone in the first gallery. Made on construction fencing and often painted in situ before being brought into the gallery, Lizen’s work is ripped from its initial context. For him, painting is both homage and interruption — a resistance practice shaped as much by citation as by invention.

Mae Dessauvage’s sculptural painting Revelation (2023) merges religious iconography with the aesthetics of digital interfaces. Her androgynous figures, rendered in opaque, candy-colored hues, gesture toward spirituality, gender, and coded symbolism. She collapses medieval visual logic and contemporary pastiche, producing a layered iconography that resists easy reading yet feels intrinsically linked to historical Belgian painting.

The flood of digital life is taken up directly in Emmanuelle Quertain’s My Address (2023), an installation of four hundred and forty watercolors based on online news images: BBC, Arte, Euronews, and more. The result reads like an unintentional self-portrait, filtered through algorithmic suggestion and deteriorating attention. As the images seemingly grow looser and more abstract, they chart the collapse not just of representation, but of focus itself. Quertain turns the digital stream into a tactile accumulation — a fragile ledger of what one sees, forgets, and half-remembers, but always records.

Sarah Smolders takes this ethos into architectural space. In Turning Oneself Into Place (2025), she uses the museum’s grooved blue stone façade as a material starting point. Through frottage, combing, beeswax, and subtle transfers, she maps the building’s perimeter onto paper. Her installation, comprised of layered prints and fading canvas “windows,” quietly indexes time, weather, and space. Smolders is one of the few artists to fully engage the institutional context, revealing how material and memory coexist within and around the museum’s walls.

Strikingly few works directly engage with conventions of display or institutional critique —perhaps partly a reflection of recent controversies within the museum itself. This absence feels telling — a kind of loaded silence that may point toward the limits of contemporary painting to mediate a contemporary condition. Still, other artists take up political space more explicitly. Luis Lázaro Matos’s Diplomatic Immunity (The Eurorats) (2025) features a mural of the European Union flag, its stars replaced by spermatozoa. The work references far-right Hungarian politician József Szájer’s dramatic escape from a gay sex party— an act at odds with his party’s anti-LGBTQ+ stance. Matos’s installation pairs architecture, eroticism, and rodents in a bizarre, satirical critique of European hypocrisy. Opposite the mural, a painted letter to Szájer appears on the large gallery windows, deepening the provocation. And yet, despite the work’s political weight, the inclusion of outdoor seating in the sparse, open space (the largest gallery in the building) diminishes its immediacy — highlighting an odd disconnect between curatorial staging and the strong formal awareness evident in many of the works within the exhibition. It underscores how in large-scale contemporary painting shows, the conventions of exhibition-making are rarely interrogated.

Painting here bleeds into sculpture, installation, architecture, and the porous digital. Some works engage with nostalgia; others grapple with broader conflated or conceptual frameworks. Many hover between tradition and transformation. Still, the exhibition resists making a singular claim. Its national framing — painting in Belgium — is understandable but occasionally feels limiting; a broader transnational lens might have sharpened the show’s inquiries, given the international resonance of Belgian painting over the past thirty years. Exhibitions such as “Trouble Spot Painting” at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Antwerp (1999), curated by Narcisse Tordoir and Luc Tuymans, remain a landmark moment marking a revival in Belgian painting. The influence of Tuymans’s generation can be traced internationally, so why limit the selection to one country?

That said, “Painting After Painting” doesn’t offer a manifesto. Instead, it rests in a space of uncertainty, allowing painting to remain unresolved. It might be taken as a quiet proposition that painting still matters. In a time of infinite scroll, image fatigue, and algorithmic overload, painting’s slow materiality, its awkwardness, its refusal to disappear, begins to feel radical. Not because it has survived its death or been resurrected — but because it never really died to begin with.