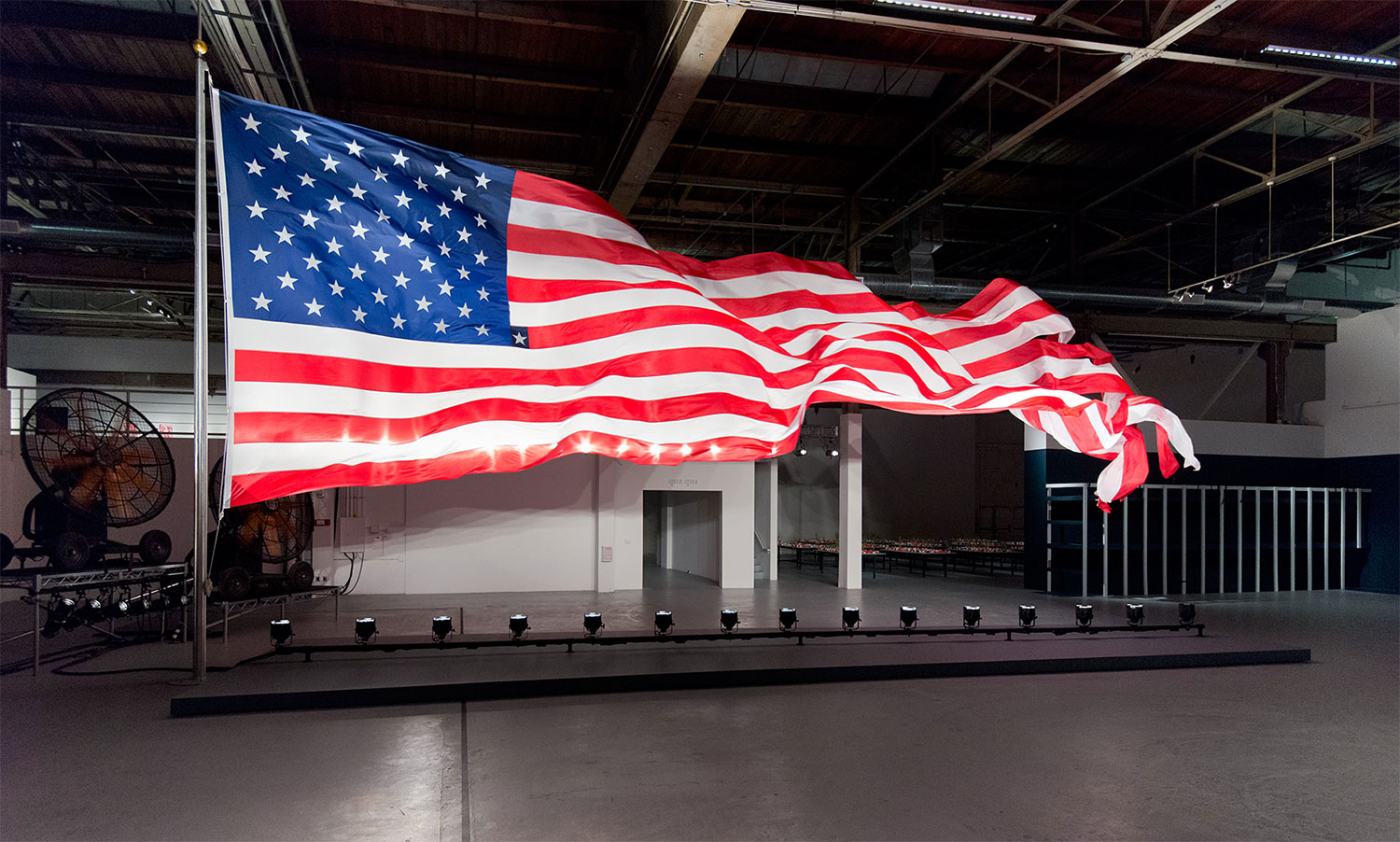

I first encountered the work of Pope.L (b. 1955, US) as an undergraduate, when he was included in the 2002 Whitney Biennial. The work seemed unclassifiable then, and only minimally more classifiable now — unclassifiable whether taken as a whole or separated into its constituent parts — and more importantly, not unclassifiable for any one reason or for no reason, but rather in the service of exploding the very scaffolding holding all of this up. More recently, Pope.L was once again included in the Whitney Biennial, this time exhibiting a duplex-apartment-sized structure within the structure, paneled, like so much aluminum siding, with actively rotting, sweating bologna (Claim [Whitney Version] [2017]). The number of slices of bologna in this case represents the percentage of Jewish citizens in New York, though one quickly finds that this seeming fact is untrue. For Pope.L the limits of truth, if they can be delineated at all, are more interesting than anything more conveniently essential. Pope.L is indeed a kind of ambassador for inconvenience, in terms of how he has positioned the black body allegorically and metaphorically as well as through his own body. Speaking, or rather, writing to Pope.L, I was perhaps less interested in delving into the essential than I was in a more scattershot look into the mind of an artist who, perhaps more than anyone working today, is — or at least seems — fearless in the face of contradiction, complication and the complexity of the everyday.

Jibade-Khalil Huffman: Anger, understood as political animus and the like, seems like more of a thing in this current moment as it relates to artmaking. For some people, this is a new thing, while other folks seemingly have been angry for years. Could you talk about your relationship with anger and process?

Pope.L: When I was younger, say in my teens, I was angry all the time. It was a survival thing cause everyone in my neighborhood was angry all the time. But being angry 24/7 took a lot of energy and was kind of boring. Eventually I had to make a decision about how I was going to spend my life, so I decided a little less angry had its upside. For example, being less angry allowed me to love easier, communicate better…

JKH: While I wouldn’t necessarily consider works like Trinket (2008) political art, and I certainly relate even your most polemical gestures to a larger experience (which includes but isn’t limited to politics), I’m wondering, what are the parameters of political art for you? Is the gesture enough?

PL: When it comes to trying to make the world a better place, enough is never enough. Need is endless. The need to fix the world is as endless as there are needs in the world. But I do not have to fix everything for everyone. That’s too arrogant and a form of self-annihilation. I think a little ego is necessary. However, I think if you make culture, it’s important to risk your making. That is, make things where the only guarantee is you’ll probably be misunderstood or fail or not receive credit or disappear or get lost in the process and make something you did not intend — and in this lack will be the thing, the goad, the bitch that will stir others to action — maybe not the action you intended but action nonetheless.

JKH: The idea that a so-called political work of art might enact real and immediate social change on a large scale seems laughable, at least to me. Are artworks just glossier essays and/or less nuanced polemics for a small part of the population, which no one else reads (with a few accessible exceptions, like Basquiat or Jacob Lawrence, to draw in school groups)?

PL: I do not believe anything a human can do can create immediate social change. Anyway, not significant social change, which is always the result of a nexus of forces and interests and interactions beyond any individual whatever. That is why I am drawn to collaboration — there is always a problem when one collaborates that you could never predict beforehand — the frame of the project eviscerates, and so does the ego…

JKH: One thing I’ve always appreciated in your work is the fact of language being placed on the same level as the fact of the body. That is, on a very basic level, the usual tendency to reduce experience to one or the other (thought or action) was made to seem suspect and replaced by a more nuanced and realistic mix of the two (in addition to lots of delving into extremes in between). I’m wondering if you could talk about the relationship between language and action in your work?

PL: I find in my work that the performance aspect, my current interests as well as my previous history, is always interacting with the language aspect, so that I see language as a means of duration, and time as a way of making meaning.

JKH: One of my professors in college, Barbara Ess, introduced to the crit process the idea of making “fake work” as a means of, among other things, disrupting the ongoing narrative about so-and-so’s work that would no doubt influence such-and-such to come up with the usual pleasantries. Can you talk about the work that you don’t share with the public? Which isn’t to say: please reveal what those things are. Rather, I’m interested in the ways in which one might complicate these kinds of perceptions of the work.

PL: Regarding work I do not or have not shared with the public: there are two ways to answer this question that immediately strike me: 1) A set of unfinished novels I was working on in the 1980s, which were part of a larger set of works called “Communication Devices”; 2) The work I do with my son. He’s nine.

JKH: Who are your heroes, or rather, who do you admire? What artists/writers do you return to continually?

PL: I admire my kid. I admire Lydia Grey. She is a friend of mine. I admire my mom. She is no longer with us. I admire Thomas Bernhard, an Austrian writer who is no longer with us. I admire Patrice Lumumba, the first democratically elected prime minister of Congo, who is no longer with us.

JKH: What is the worst movie you’ve seen ever, or recently (whichever interests you more), and what is it that interests you/turns you off most about that movie? I’m curious about your relationship with “bad art.”

PL: I think my candidate would be Bowfinger (1999) with Eddie Murphy and Steve Martin. I own three copies. All VHS. Murphy plays two roles. The more interesting of the two is his Jiff character, who is an innocent who has braces and wants to please and be a better actor.

JKH: I’ve tried to keep these questions within the realm of general interest, but as an artist working across various media, I’m wondering if you could talk about working in this way and how you decide, as it were, on how to make the thing you are making? Is it simply intuitive?

PL: Intuition is key to a lot of pursuits, art being only one. For me, intuition has to come out of experience and calculation. I find that I need a balance in my decision-making — intuition never purely gets me there. It’s only after I’ve done the boring or ridiculous part that I can even realize my intuition.

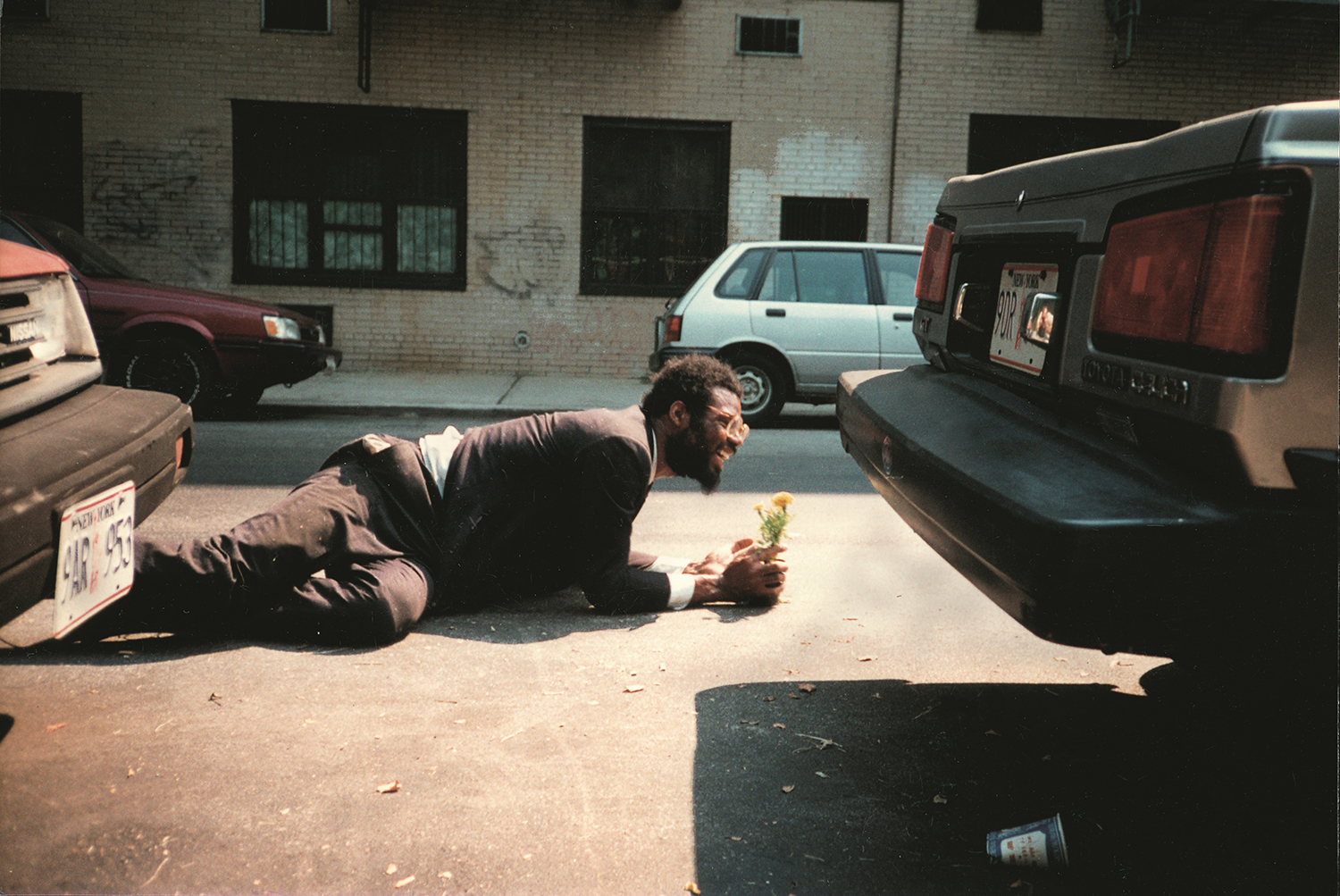

JKH: Abjection, in the vague sense that I suppose I mean here, was key in certain earlier performances, though more recent works seem to engage in a similar fashion, though on far less grotesque, for lack of a better word, terms. What does an engagement with the body mean for you now, and what did it mean for you then when you were working in that earlier, more rough-and-tumble mode?

PL: Nowadays I think it means engaging with dying. When I was younger it meant the same thing, but I was not aware of it, or I didn’t want to be aware of it. Maybe it just seemed too literal or corny or predictable. It is! Predictable, but in the most unpredictable of ways.

JKH: In lieu of a question about race, whiteness, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Claudia Rankine, Charles Barkley or Tomi Lahren, I’m wondering if you have any advice for younger artists on how to survive, as it were, this racist, sexist-ass art world, short of dropping out and/or attempting to burn it all down?

PL: Attempt to burn it down. I would find that interesting. Maybe more interesting would be after the attempt, let’s say one succeeds — then what?

JKH: Who/what are you reading?

PL: Luc Tuymans: I Don’t Get It by Gerrit Vermeiren (Ludion, Ghent, 2007); The Longest Fight: In the Ring with Joe Gans, Boxing’s First African American Champion by William Gildea (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2012); Image Science by W.J.T. Mitchell (University Of Chicago Press, 2015); Blackass by A. Igoni Barrett (Graywolf Press, Minneapolis, 2016); Custom Lettering of the 60s & 70s by Rian Hughes (Carlton Books, London, 2014).

JKH: Is there an end to symbolism? As in, is there a point at which one thing starts to cease having meaning as a stand in for something else and takes on a different meaning altogether or perhaps no meaning? Are we in that age, in this era of disputed and alternative facts?

PL: Humans are slaves to meaning. In a sense that’s what politics is. Of course none of this matters if you are the Buddha — then you are a slave to nothingness.