We’re going to the window to look outside. That’s always more fun than learning to read on lips things that, most of the time, we’d rather not know, and about which we don’t have much to say. But we do have things to say, lots and lots of things, but no one’s interested.[1]

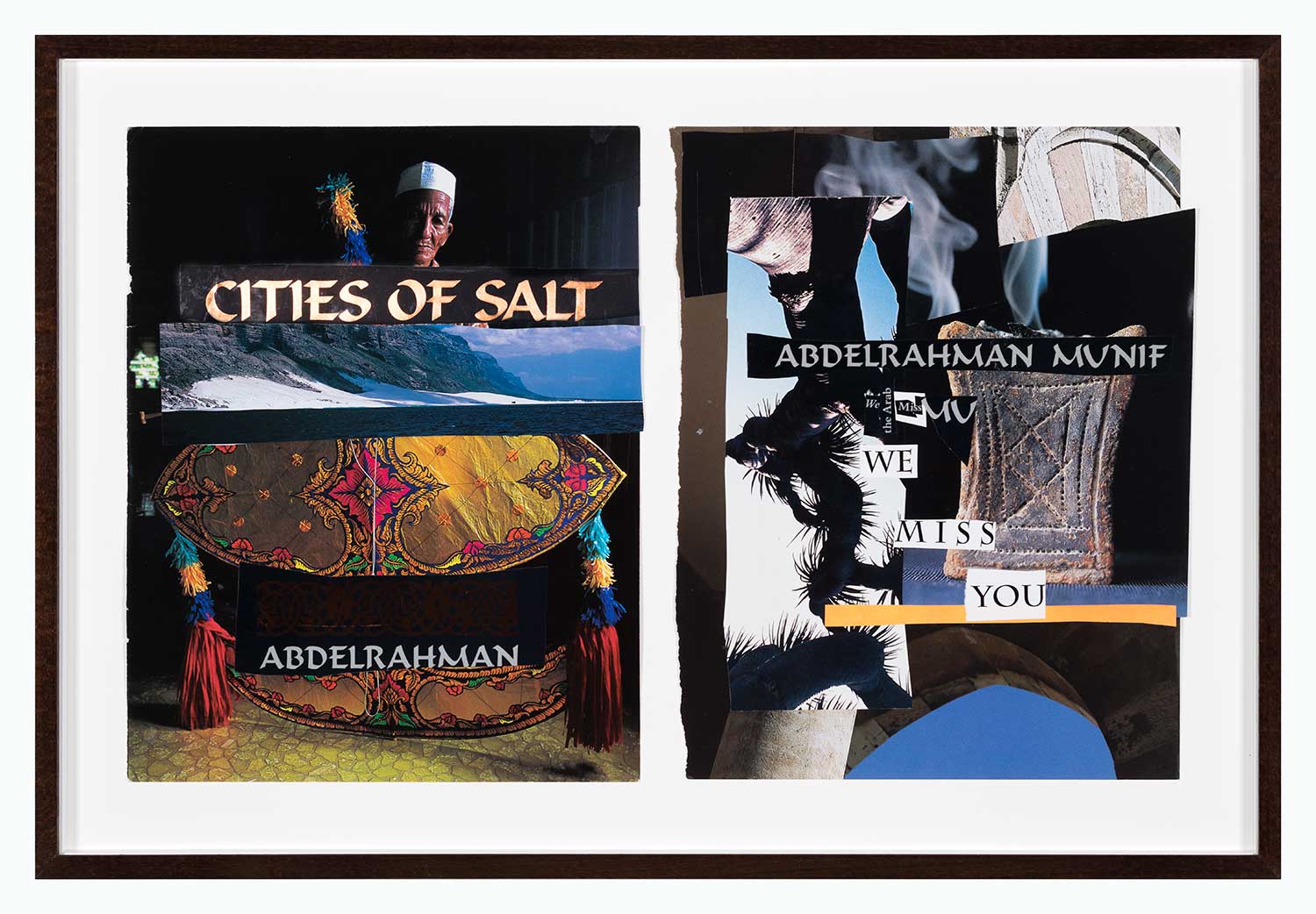

Simone Fattal decided to become a publisher in 1982. It was in response to another publisher’s rejection of a text authored by her friend. The publishers asked the author to reshape the content of the text to suit their publishing vision and market. Convinced of the potential of the existing text, Fattal decided to publish it on her own. With the help of a young self-publisher, she was introduced to the logistics of the world of printers and typesetters. She learned how to issue an ISBN and lay out a book, and she chose a name for her publishing effort. Since this space of personal effort would be shared among many, she chose not to name it after herself, but after what the universal moment of a human footstep on alien ground makes of us. “Somehow the Apollo program, that took man to the moon,” Fattal says, “was extremely important to me — it was like the new age starting.”[2] What does one make of an age that comes after realizing that we can be outside the limits of our immediate world? Post-Apollo Press was born of this new relationship with order: attempting unimaginable encounters, creating methods that have their own order of existence, launching projects that carry their own oxygen. Projects that do not require their makers to consider the market but that require the market to consider them.

“I said, Post-Apollo, and then the logo is the moon, the crescent moon.”[3] The Levant, where Simone Fattal is from, often looks to the moon. Beauties are named after the moon, rituals await its appearance, time is calculated based on its shape, and suspense surrounds its eclipse. Even the light that the moon emits has a different name in Arabic than that of the sun; it is acknowledged to be a reflection, a redirection of rays of light that hit a surface willing to illuminate back. The moon is a publisher, of not just the light but of what the light inspires.

There’s granite in front of us. The mountain range is raising itself over the horizon and we’re celebrating your victories, not ours.[4]

In its founding year, Post-Apollo published what would become its bestseller, Etel Adnan’s Sitt Marie Rose, translated into English from French.[5] It is a novel about a female teacher who is able to communicate in a way that transcends words, particularly with children who are deaf. In the novel, the life of the protagonist is threatened, and so was the life of its author who had to leave Lebanon and settle in California. The space of intolerance in the novel is related to the time and place in which it was written: during the Lebanese Civil War, which had exiled Fattal and Adnan into the United States in 1980. Adding further intolerance to the context of the book’s publication was the Israeli invasion of Beirut, during which it came out. The cover, Fattal says, was “commented [on] at length by one of the first reviewers of this book when it first came out. They said it was a political indication, it was saying: ‘This is Lebanon, and don’t trespass!’ I must say that the book was published during the Israeli invasion of Lebanon and yes, the idea of drawing its boundaries and existence was paramount in my mind.”[6] The cover showed a map of Lebanon, with a series of mountains designing its terrain. In addition to the mountains that in equal parts transcend and define the borders between Lebanon and Syria, on this map there are roads linking Damascus to Beirut and Sidon to Baalbek, as well as al-Asi (the Orontes River), which runs rebelliously from south to north. So were the channels that carried this and subsequent Post-Apollo Press books to readers: “A lot of feminist presses discovered Sitt Marie Rose and helped me by distributing the book with their publications.”[7] Once released into these channels, the novel “moved on its own, by word of mouth. It’s taught at many universities every year — its academic success I had not foreseen at all. We still continue to receive letters from students addressed to Sitt Marie Rose, as if she were an actual person.”[8] The book as it moves is a living entity; it makes friends with minds, imaginations, and future worlds. Through the same channels, proposals for literary and poetry books returned to Fattal, who would match the texts she published with illustrated covers, placing them within different series and exploring unique typefaces and formats. Whereas the authors were experimenting with their writing, the artist-publisher was experimenting with bookmaking not shaped by aggressive markets or trends.

Do colors have the power to break the time barrier, and carry us into outer spaces, not only those made of miles and distances, but those of the accumulated experiences of life since its beginning or unbeginning? Color is the sign of the existence of life. Now the clouds are grandiose and turbulent. An autumn storm is coming. Whatever makes mountains rise, and us with them, makes colors restless and ecstatic.[9]

For Fattal, chance is not a mystic force but the rough conditioning of a substance, the life of a substance that has been lightly touched with intervention. Such roughness is seen in her sculptural work, which inhabits a place between the form of the material and Fattal’s intervention on it; she does not force one entity on another. By 1989, Fattal had returned to making artworks, after enrolling in a sculpture program at the San Francisco Art Institute. She might work a translucent, pink alabaster rock into a statue like something found on a contemporary archaeological site. In clay, she impressed the deepest forces of her mind,[10] creating mountainous terrains with her fingers, rendering the mountain upon which she had fixed her gaze from her studio, before she left Lebanon. She painted it in all its combinations of color and form: “Pink before sunset and white after sunset. Very white. And so, I was very much obsessed with those transformations.”[11]

Color choices are essential here. Consider the cover illustrations of the poetry series that brought forth the works of Etel Adnan, Oscarine Bosquet, Cole Swensen, Amin Khan, Denise Newman, Ryoko Sekiguchi, Elfriede Jelinek, and Joan Retallack, among many others. Three rectangles are placed diagonally on a square space under the author’s name and book title. The combinations of the colors change from one book to another, and the variations imply the unity of the series but also the particularity of the content. Each treatment attempts to match the text to a cover/color in keeping with its spirit — design choices informed by the artist’s beginnings as a painter.

Besides all this knowledge of making and makers of books, of painterly and sculptural work, and of the geography, archaeology, and history of the places she has lived, Fattal is a generous advocate of the work of her partner and collaborator, Etel Adnan. She has a vivid memory of when each work was made, in which context and with what title. Coupling this with her publishing work, one can start to imagine the infinite character of Fattal’s knowledge and experience.

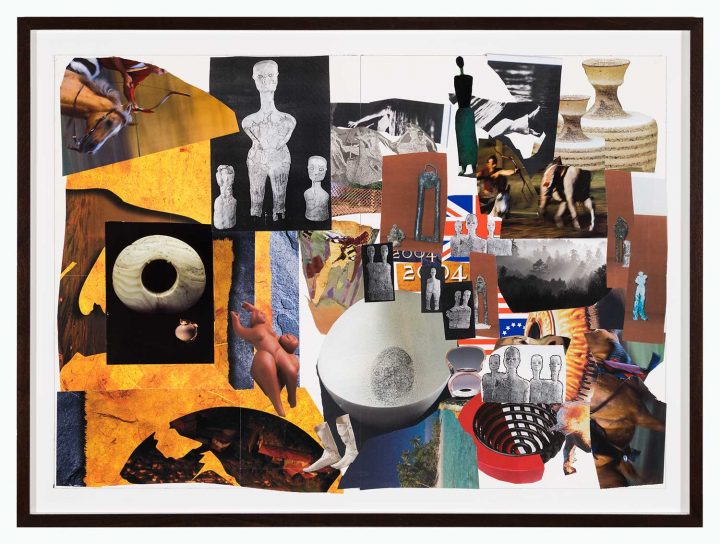

When I met Fattal a few years ago, she told me she would pass on her literary project to a younger publisher; just as, early in her career, she decided to end her painting series. On the subject of this decision, she has said, “One day, I knew it was the last mountain. I put the final line with a red stick of chalk — I knew it was the final line — I had seen all the whites, all the pinks I could see. I had said pretty much everything I had to say about it. […] I worked for ten years and I made a statement and that body of work was done. It was as if I had written a book that was finished.”[12] Fattal now moves her sculptures from one continent to another. They could all be the mountain she had seen from her studio, or the humans whose figures have survived through time. Inspired by her archaeological expeditions in Palmyra in the 1970s, she produced Palmyra (2014), in homage to an ancient Syrian city that was about to see the brutalities of destruction. “Where we come from, the past is always part of the present,”[13]she says, referring not only to the place that such a history carries in her own memory, but also to the wars of the past as they reproduce their violence in the present.

One of her 2016 pieces, Cliff (2016), is a clay cliff covered with dark green glaze. The texture is soft but the geography of its surface is not. Some parts are steep, while others are sculpted, rounded, imprinted with finger pressings. The glaze has softened at some of the edges, moving between variations of green as it seeps down the steep edge of a mass that resembles a mountain. In another piece, Turtle (2017), a lump of red clay partially covers a black mass. The mass’s surface is a terrain of tiny hills that are the work of fingers and palms. The form’s reaction to heat has left beige cracks on the surface. The red shell pours in abundance over parts of the composition. Another angle shows that the mass is not entirely solid — there are spaces left under it from the way its irregular edges stabilize it on a surface, like a creasing mass attempting to shrink upward. Fattal’s mountains tear down, shrug as they stain their surfaces with seemingly raw remains of a process. The materials have their own substance, content, form, force, and will, and Fattal finds how they can exist between their forms and her intervention.