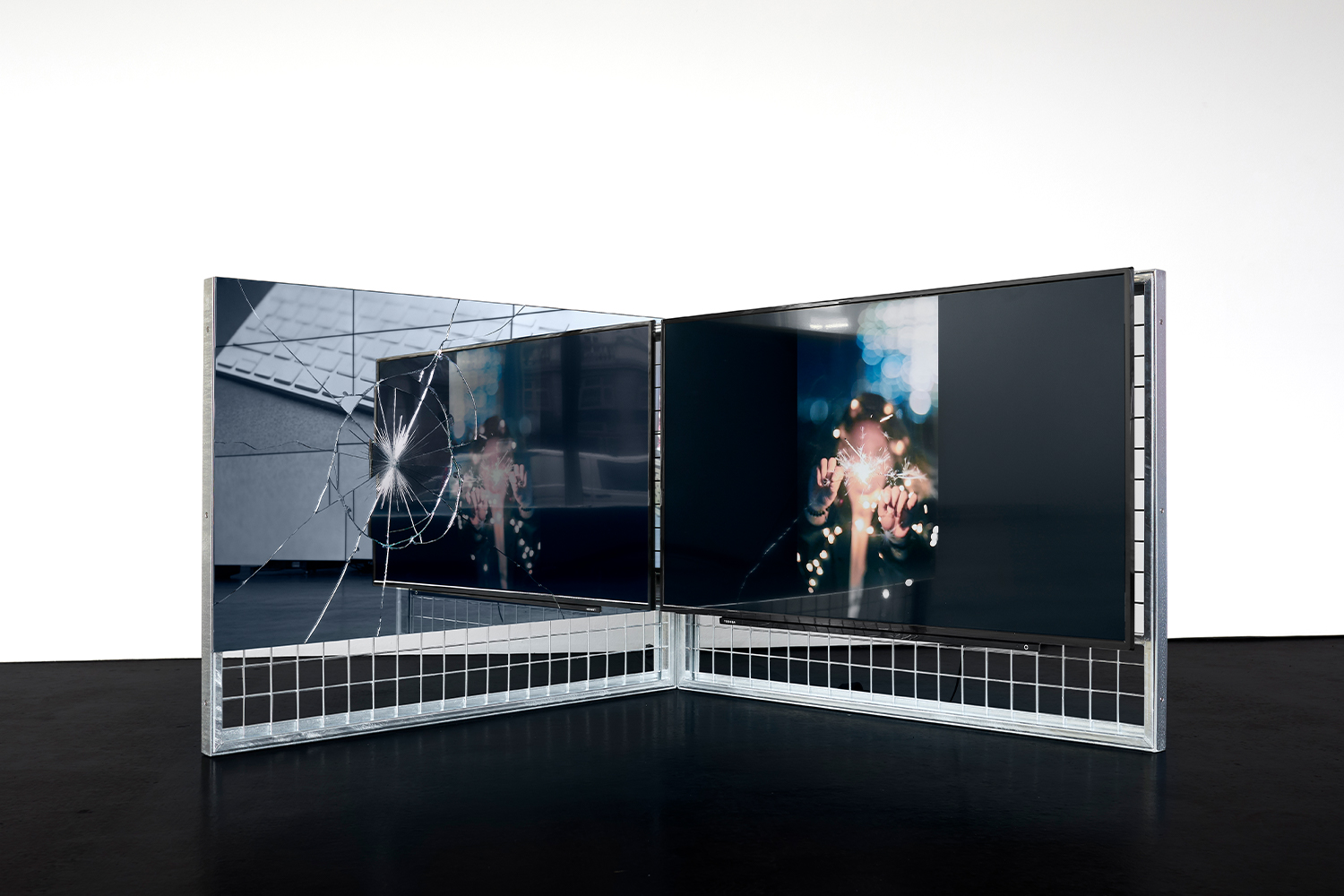

For the performance work Lord of the Flies (2021), Shuang Li remotely trained twenty performers, each following a script, to embody the sense of failure and implosion that defined metropolitan cities during the pandemic years. The performance is about the absence of human presence, both contingent and conceptual, as well as the metamorphosis of interpersonal relationships during a historical moment in which humans have become ever closer to a state of dematerialization.

Li herself hasn’t been home in two years. Despite her best efforts, she has been stranded in Europe because of the pandemic. Lacking a real studio, she moves between Berlin and Switzerland, trying to metabolize the meaning of human existence in a given place.

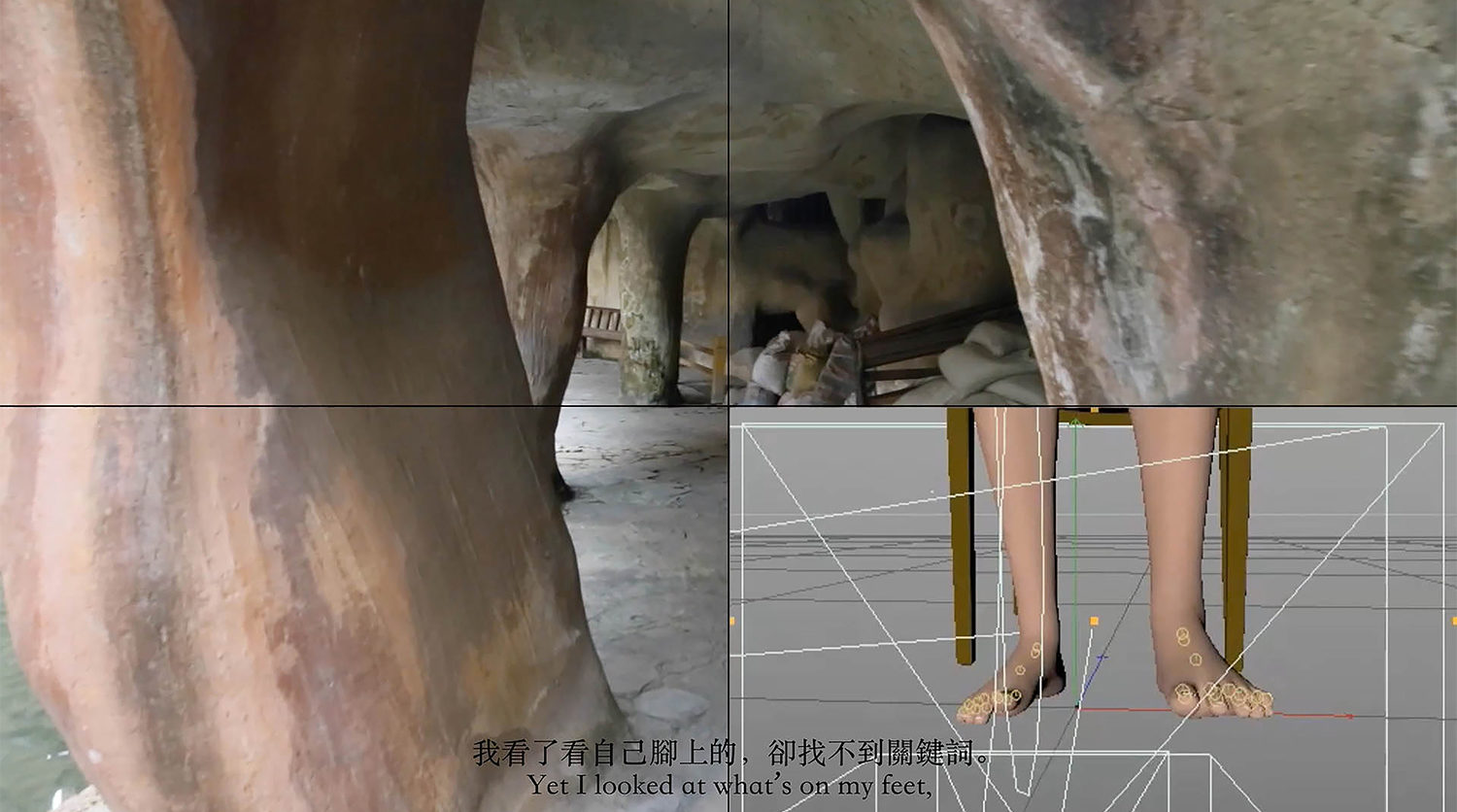

The sociopolitical dimension of her work, from the very beginning deeply shaped by her life experiences, in recent years has been largely informed by absence; the lack of belonging to a place — and to a culture, with all that that entails — has been decisive. Her ongoing research into the projection of human identity onto digital platforms and the increasing use of artificial intelligence in everyday life takes place in fictional media landscapes rendered via mash-ups of historical eras and cultural backgrounds. Shuang Li’s characters are hybrid entities, technological and genderless, and communicate like characters in a video game, renouncing a purely corporeal dimension as well as any dialogic link to coexisting entities.

Li’s research often starts from her own body, from the study of desire and affect, which she reflects back in fictitious narratives across disparate temporalities and geopolitical contexts.

In the following conversation with Andrea Bellini, the artist tries to reconstruct the roots of her interest in seeing the world “for the first time” through images and the body, trying to understand the essence of digitalized intimacy amid the existential restlessness of the world around us.

Andrea Bellini: Dear Shuang, since the start of the pandemic, you haven’t returned to China. In 2020 you went to Berlin for a show and you’ve never been able to return home. Your body seems in transit, in a state of placelessness. I was thinking that, well before the pandemic, which made everyone’s life more complex and static, you were already interested in the question of the contemporary body, in its political status, but also in its increasingly virtual dimension. Will you tell me where you come from and why you started to deal with these issues?

Shuang Li: I have long been fascinated by different mediums. As our lives keep getting more and more mediated, it’s actually hard to remember that a body is physical in the first place. I was born in a small town in China. As a child I spent most of my time reading and playing video games — maybe that’s where everything started. My dad is into Russian literature so I got to read a lot of those. At the same time, my parents got me a knockoff Nintendo, and now looking back I think that’s when I got to see the world for the first time. Of course it was a highly mediated one, but no less than how life is today. During my teenage years the urge to escape not just my immediate surroundings but also my own body had become very acute. That’s when I first heard punk and emo music, which had a huge impact on every aspect of my life. I came into contact with punk and emo through dakou CDs — CDs that were overproduced, and the record labels would punch a hole in them to strip them of their value as commodities in order to dump them in Asia as digital waste. Eventually somebody found out the hole would just damage one song, if at all, and as a result these CDs started circulating. Dakou CDs in Chinese means “CD with a hole.” I think these CDs have become a forecast of my practice — I’d like to think my works break smooth surfaces and connect different dimensions.

AB: Video games and punk music sound very interesting as an early approach to the moving image and the sound track. What exactly do you mean when you say that you started seeing the world for the first time when you got your knockoff Nintendo?

SL: What I mean by “seeing the world for the first time” is, in a literal sense, how the world was portrayed in the games. For example, a lot of video game backgrounds are set in New York, so I believe that’s when I first saw the city, similar to how people find New York familiar the first time they go there because of movies. But contrary to movies and TV, while showing me how the world out there can be drastically different from my immediate surroundings, the world in video games was still within my reach as I interacted with the scene and figures through my controller.

AB: And later you ended up studying art in New York. Did you find the city lived up to the image you had formed of it through video games? [laughs] How did you find the study experience and the New York years? I imagine it’s not easy to land in the US coming from a small town in China.

SL: In some ways the lived experience really aligned with the images from the video games! It was not easy for me, but years of listening to American bands helped a little.

AB: Some of the work you’ve done during your time in New York is related to the issue of immigration, the experience of being a “foreign” body or an “other” body. Would you like to talk about that?

SL: My perception of “foreign” and “other” has changed a lot since then. In New York I was still in my teen angst period, and I felt, like: “I don’t belong anywhere.” I’m not saying I grew out of it finally, but after the last couple years of moving around in the world, I have noticed I’m good at finding connections between different locations and cultures, so wherever I go I can make myself somewhat at home. Maybe it’s just a coping mechanism against this placelessness. But looking back, there seem to be lines connecting the places I have lived, composing a constellation of stars instead of remaining as separate dots. I have been making sculptures based on the imagery of seashells. A seashell is the home of the creature that inhabits it, but vendors at a tourist beach will tell you, “You can hear the sea through it.” In this sense they can also be a medium, a conductor. Once it starts circulating, it becomes an empty shell where the tunes once lived. I guess these new works are also a way for me to process this placelessness.

AB: Your father’s interest in literature during your childhood seems seminal. You often speak about the importance of writing in your work. Is this something you would relate to the years you spent reading Russian literature?

SL: Maybe “reading” was too big a word for that. Looking back, I don’t think I even understood much in those books. In terms of writing in my own work, I do think it’s somehow been impacted by this experience: even though my moving-image works are usually text heavy, I believe people don’t really need to understand much of the text or the background to get into my work. I’m constantly asked to explain my work and the cultural background to which it relates. There seems to be so much explaining to do, and still so much that is lost in translation, partially if not completely. But I don’t think it’s important after all.

AB: Certainly what is lost is much more than what is understood, and I understand your discomfort in talking about your own work. The Italian writer Giorgio Manganelli, to return to the question of literature, argued that the author does not even exist. This conviction was connected to a polymorphic, iridescent ideal of personality — to a critique of the self as something stable, knowable, representable. Around the idea of the artist-author, its progressive cancellation, absence, and the relationship between public and private, you’ve done a pretty curious work. I’m talking about If Only the Cloud Knows (2005–18). Can you tell me about it?

SL: I really like your reading of author and authorship. If Only the Cloud Knows starts with some personal trauma that I wanted to forget at that time. While it’s not that hard to block it out mentally, traces of those events can find their way back through external memories. I didn’t have the heart to delete those, so I made a website where I uploaded all my digital memories for the past ten years, from texts to all kinds of images on my phone, computer, hard drive, etcetera. I made it available for visitors to delete anything they wanted, as long as they left a note, while deleting all other copies from my end. This work started with a very selfish intent, but I was also very interested in researching how external memory devices affect our brains, and what’s the essence of digitized intimacy. During the course of going through and uploading my personal archive, the shifting of the media landscape of the past decade also flashed before my eyes.

In some way, very personal and intimate works are the ones that can touch the public the most. I was very inspired by Chiara Fumai’s show at Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève. It must be a very personal project for you as well. Though I would describe her works more as intimate than personal, the curation made it a very personal and touching experience for viewers. Like, we set foot in a replica of her apartment, and from there we entered her oeuvre. The exhibition for me was a medium for reaching her.

Relating to If Only the Cloud Knows, there’s a funny anecdote: at the beginning it was hosted on another URL, but for a while I forgot to pay for the domain so the URL went back on the market. Shortly afterwords, a porn production company purchased the domain and it became a porn website. For a while people who clicked on the link from my portfolio would end up on the porn site. I didn’t realize it until a curator asked me about the work, super perplexed.

I’m not too familiar with Giorgio Manganelli’s work, but these days I find myself thinking about one of the stories Italo Calvino wrote in Cosmicomics, titled “The Distance of the Moon.” According to the story, the distance between moon and earth used to be really short. At one point in their cycle they would even get so close to each other that people on earth could pull out a ladder and climb to the moon for one night, and go back to earth before the planets drew away from each other. One night, when people got to the moon as usual, gravity changed drastically. The moon suddenly was drawn away from the earth. Amid chaos, some people managed to get back to earth, but some remained on the moon forever. I use it as a romantic filter to look at the pandemic, not just for my own but for the planetary situation.

AB: An interesting idea to look at the pandemic through Calvino’s “The Distance of the Moon.” Perhaps we should all ask ourselves if we remained on the earth or on the moon. And I’m happy to learn that the Chiara Fumai show left a strong impression on you. Both of you put the body at the center of the work, although in a diametrically opposed way: Chiara’s is still an organic body — her body — full of physical moods, even if astral and elusive. Yours is often a digital body, a subjectivity increasingly entangled with an immersive online culture. I’m thinking for example about I Want to Sleep More but by Your Side (2020). Can you please tell me how this complex work originated?

SL: My works engage predominantly with the relationship between body and screen, which I think is now completely reversed. Before we had our physical bodies first, then we had representations on different mediums, like photographs and paintings. But now, if we don’t have a screen body, our physical bodies don’t exist either.

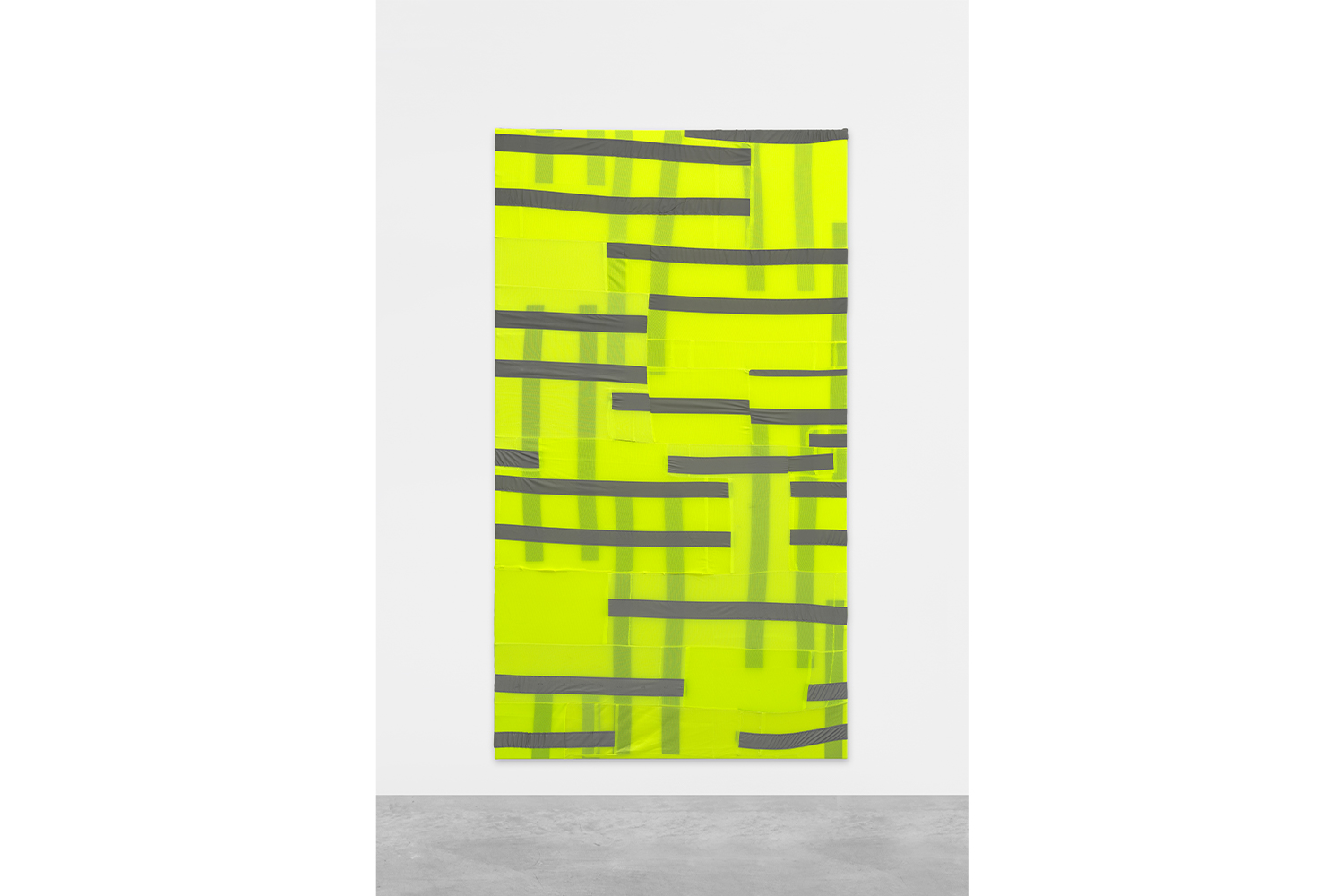

I think I first noticed this transition when I was working on I Want to Sleep More but by Your Side, which departed from the production and circulation of yellow vests. It later grew into a fictional online romance between a young boy working in a factory and a French mother who was involved in the gilets jaunes movement. Yellow vests are everywhere in real life, but it was only after seeing them on my screen, lighting up the streets of Paris in a context of civil unrest, that it started registered in me. I started to see them on the street, but even in real life they look so unreal — they are so thin, stiff, and transparent. They move clumsily on the bodies wearing them. They look like a bad filter, pixels leaked from screens that have congealed in real life. I think this reversal was completed during the pandemic, coined by writer and curator Alvin Li as “planetary camgirlization” — we were all reduced to our performance online.

Working with the idea of leaked pixels and congealed realities, I’m making a new video for my upcoming solo show at Peres Projects. In this video, flip-book animation is used to address leaked pixels between pages, like leaked pixels in circulation, while connecting the movement of flipping with the gestures of swiping and scrolling on the screen.