RoseLee Goldberg: Shirin, it would be really interesting if we could begin with a comment from you about moving across mediums and what it felt like for you to create your first live piece in 2001.

Shirin Neshat: Let me begin by saying that ever since I’ve become active as an artist, I’ve taken a very nomadic approach to art forms. I have moved rather quickly from photography to video, to performance art, and then toward cinema. At times I’ve wondered: Why so much change? Why am I so restless? And I’ve come to the conclusion that ultimately an artist’s work is a reflection of the artist’s life and personality. I’ve learned to live as a nomad. I’m constantly on the move. I’ve never seemed to stay at the same place for very long. I’ve embraced the idea of new beginnings and I’ve felt the need to reinvent myself. In fact, I am terrified of stagnation and repetition. When I made the transition to filmmaking, as ambitious and difficult as that process was, I enjoyed the challenge and the elements of the unknown very much. In many ways, all these transitions have kept me on my edge, and have made me feel vital and relevant, not in respect to the art world, but to myself as an artist, feeling that I’m still learning, growing and experimenting. Going back to photography, I remember my first series, called “Women of Allah,” had a performative quality in the way that I posed for the images and played various roles. Later, with the videos, the physical design of the installations created a situation where the audience was seated in between the two screens, witnessing the story in two parts, never quite able to watch both sides at the same time. Therefore, the audience literally became a participant in the piece, as they were physically divided and engaged with the narrative. Later, cinema taught me about reconsidering the audience, as I moved out of the gallery and museum walls, away from a purely commodity-driven enterprise and toward a general public. When I first did live performance, I was terrified. Unlike film and photography where you can take time and edit, there is something unnerving about live performance where you loose a certain amount of control; and you find yourself at the mercy of chance, accidents and the chemistry of the audience and of the performers.

Wangechi Mutu: My performance Stone Ihiga in 2009 was created to try and understand what happens when communities decide to victimize particular individuals. The performance is based on a narrative about women who are about to be stoned or persecuted, but we never mentioned or explained that to the audience. We brought the people into our space while we were beginning our performance. At some point everyone sat around, and the waiting began. The performance was really about waiting for something to happen. I felt one of the most powerful things about violence is how impossible it is to explain, especially if it is something you haven’t experienced. I wanted to twist this around and ask what if someone was waiting for something very life threatening and frightening and transformative to happen?

There is always something about the violence of Africa in my work, the partition of the continent that is always present in my collages and in the way I go about implying what happens to the female body. This performance needed to address that issue, and in a way I chose to address it by making people wait and wonder about the imminent violence that was to be experienced by these women. As for the title Stone Ihiga: Ihiga means stone in my mother language. It is also the name of my uncle, whose daughter, my cousin, was victimized as a woman as she had a mental disease that was never really dealt with. She ended up dying because of the lack of support. Ihiga is connected to her and really the whole piece was dedicated to her.

RLG: Can you talk further about being terrified by live performance and also about the difference between working in live mode and in film? They are very different worlds. In live performance, rehearsal can take weeks. Shirin, you once asked me, “Why do we need a whole week for rehearsal?” I said, “You will be grateful later on.” Afterwards you said, “Thank goodness we had that week. It has taken so long to figure it out.” You do need time to build the work during rehearsal. Another thing you said that was fascinating to me was, “Eye contact.” You said that there was something incredible about being with the audience. Could you talk about this more?

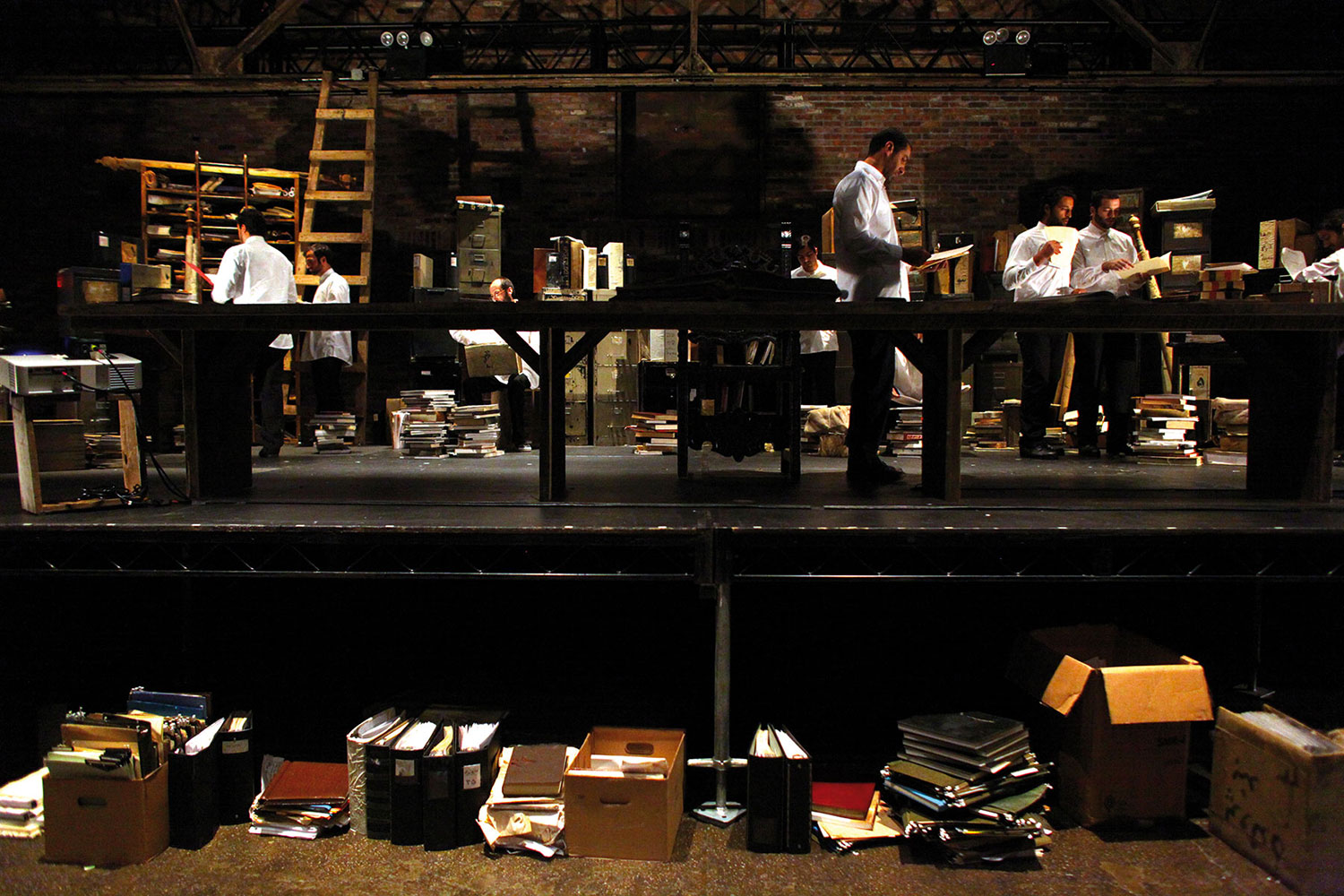

SN: The first live performance I did was Logic of the Birds. I was coming from making photographs and 10-minute-long video pieces, so the idea of making a piece that lasted around 60 minutes, and that had a form of development (a beginning, middle and end), became a challenge. I realized that coming from still images and short videos, one rarely thought about the audience’s attention span, as they could simply walk away. But in both film and live performance, you have the audience’s full attention for much longer. Therefore one has to carefully calculate the narrative comprehension as well as the pacing and dramatic arc to keep the audience interested. I struggled with all of this at the beginning, as I realized that I was far more experienced in creating provocative images than in telling stories. Most helpful in that regard was to surround myself with people who have the skills and necessary experience, such as my longtime collaborator and partner in life, artist and filmmaker Shoja Azari. Throughout the past many years, I have learned that as artists we must not overestimate ourselves. For example, just because we have made short videos, we are not qualified to make a feature-length movie. Or if you have done photography you are not necessarily fit to direct a performance piece. While we must take risks and experiment, we must respect and learn that every art form has its own language and set of rules. So blurring the boundaries between forms comes with a certain amount of education, responsibility, of course excitement, and anxiety!

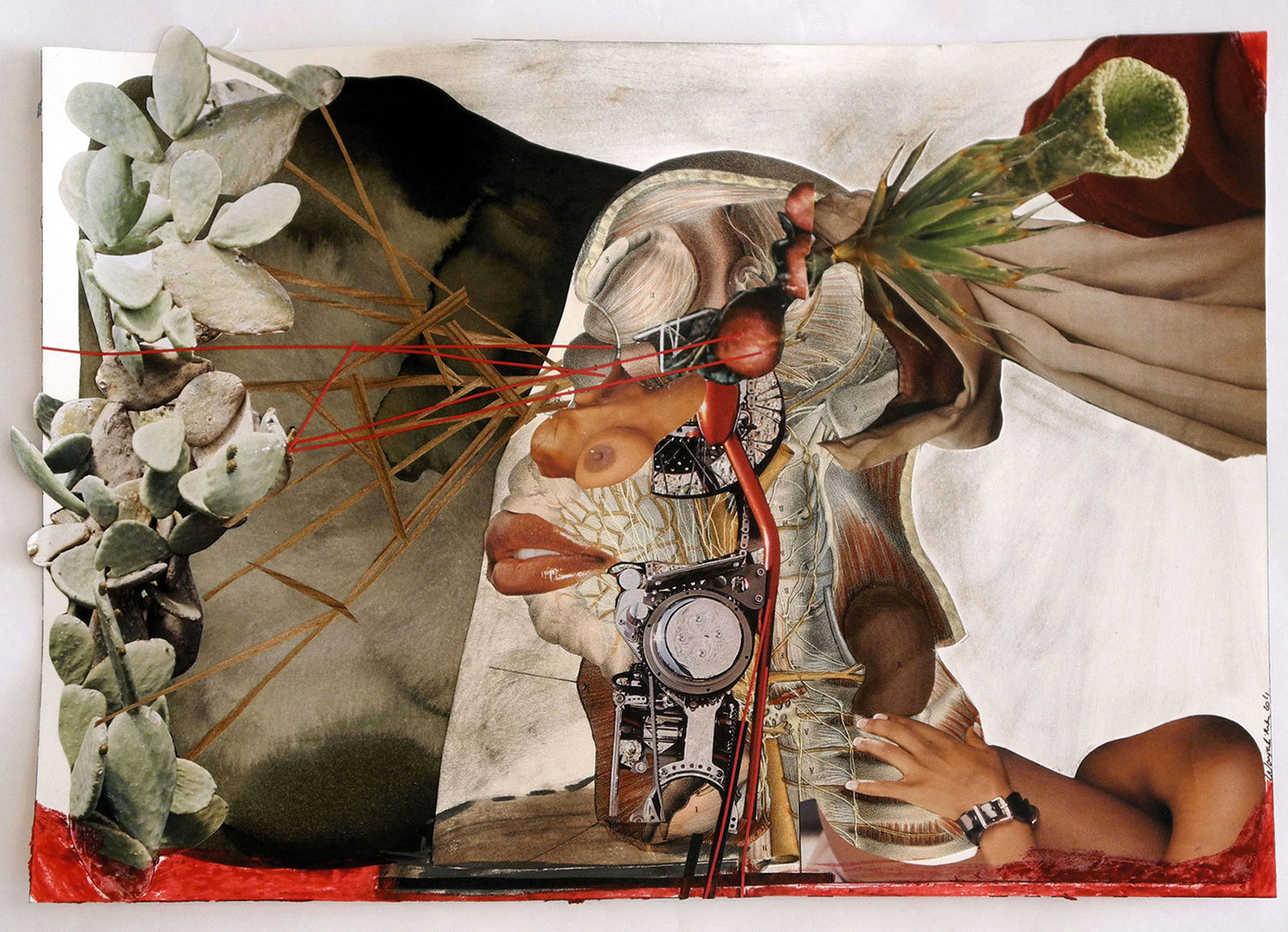

RLG: Wangechi, can you talk about your collage? There is so much political and anthropological layering. How do you use the different mediums to infuse the layers? Do you think of collage and video in different ways? Does performance bring these different parts together?

WM: It’s hard for me to divide them cleanly and clearly. Most of the performances are done without an audience. I have a soundperson, a cameraman and myself, so either they were done in the studio or somewhere in San Antonio, Texas, or on a deserted street here in New York. My performance Stone Ihiga was the first time I had this challenge of working with a team. I was terrified, as I usually work very privately. Collage is a necessary madness of mine. There is something about the obsession, the way I perceive images, that pushes me to cut up photography and material in order to make collages. What happens when I perform is that I decide to become possessed with those subjects that I am representing or speaking for on the flat surface when I make collage; so instead of trying to understand it, I actually become it. I don’t do many performances. It was very particular moments that pushed me to wanting to enact and exorcise something, to emit a particular frustration.

Cutting (2004) really came out of an intense frustration; I was in a moment when I found myself geographically out of my comfort zone. I had left Kenya and had moved from New York to San Antonio, Texas, for an artist residency at Artpace. It was the middle of the Bush era, and I remember looking at Texas and thinking, “This is the source of a lot of these issues that are coming out of this leadership.” After a few weeks of research and thinking, “Why am I here, how do I inspire myself in a place that gives me nightmares?” I decided that this issue was universal. The lack of humanity, this refusal to address issues through diplomacy, through regarding the problem, rather than just jumping into war without thinking or pausing. I thought: What is it about me that could possibly be like this issue? Instead of pointing the finger, how about I decide to be the perpetrator? When I enacted this cutting piece I was thinking about Rwanda, about women’s work and the connection and confusion between the weapon and the farmer’s tool, especially in Africa and Rwanda, where there were hardly any guns used — mainly machetes, knives, pangas and clubs. It was such a personal massacre and was so close to home, and I wondered what would turn people to do this kind of thing? It said to me: First, this kind of thing could happen anywhere. Secondly, it is easy for you to want to be in the position of the killer, of the persecutor. Cutting came easy for me. I was trying to cut a pile of wood and the sun was setting and so we were tackling this issue of time and light and sound. I was getting very tired and exhausted, and the image I captured for cutting, which was a six-minute piece, was the very end, where the pure exhaustion had gotten me and my knife got caught in a piece of wood. What happens for me in collage is I am able to separate myself and sort of mediate through the process of thinking about these issues that are important to me — issues of beauty, violence, politics, spirituality, etc.

RLG: Shirin, how did your first live piece, Logic of the Birds, affect your subsequent work? Now that you are doing another performance, are you ready to go through that anxiety again?

SN: The first time I even allowed myself to think about a live performance was when we were shooting Rapture, a video I made in Morocco back in 1999. There were several highly choreographed moments, as one hundred women in black veils moved about in a natural landscape, as well as one hundred men in white shirts in a fortress. As the men’s and women’s bodies moved in lines, circles and triangles in juxtaposition, an odd visual and aesthetic experience was created not unlike a dance performance. The live experience of watching these bodies move in various landscapes was so incredible that I suddenly thought about how powerful it would have been if my audience had been physically present to watch the actual scene unravel live, as opposed to encountering only its representation in the form of a video.

RLG: Wangechi, do you want to add to that what you were thinking of, in terms of the Stone Ihiga performance, when you go back to making your beautiful collages?

WM: This question of how you make art present for everyone, as present as it is for you (the artist) when you are making it, is something we tackle all the time. Performance is very much to me about addressing and bowing to the fact that it is so important to be in sync and unite ourselves in a space to experience something. The most wonderful thing about the opportunity to do the show at the Deutsche Guggenheim in Berlin was that they basically give you carte blanche. My inclination is always to turn the gallery space into multi-sensual area, to make all the senses work in tandem with each other. I used a gong sound to make a heartbeat. Almost like a murmur inside the body that wouldn’t necessarily be like the collage works or the installation with wine and milk dripping. The gong sound made the bottles vibrate a little bit, a tremor; things almost tremor as though one unit, one body. In any situation where I have a daunting or very sterile white space looking at me I try to bring it to life in many different ways.