“And yet there is a sense in which the painter also creates a bed?

Yes, he said, but not a real bed.”

— Plato, The Republic

When I first learned about the existence of Jorge Luis Borges’s “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote,” 1 I had just begun to digest the Adornian aesthetic. Honestly, I was thrilled by the idea that artistic objects could be shrouded in such mystery, always conceptually open and free from any definition — that objects were, in essence, “indefinable.” Mine was a long and complex process of understanding and assimilating the positions of Wittgenstein and Weitz, who denied the classification of art, which was only “synthetically” understandable through a never-explicable feeling. My process of understanding therefore suffered a setback when I came across the case raised by Borges. In his short story, the Argentine writer compares two works: the original Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes; and another story written by an imaginary author named Pierre Menard. Despite being two different works, the two texts are syntactically identical. As I thought about what could be the difference between the two, if in fact they were identical, I asked myself: “Why did Menard even rewrite the Quixote?” Indeed, Borges’s expedient was excellent. After all, as early as 1939 he was using literature to test such concepts as originality, copy, translation, and contingency.

The answer to my question would come from Borges himself, who observes that the two texts differ in that they belong to different historical backgrounds that make them characteristic of their own time. Although Menard uses the same words in the same order as Cervantes, the difference is that he refers to the “land of Carmen” — which belongs to nineteenth-century literature and was probably influenced by Flaubert’s Salammbô — as an example of a historical novel. Contrarily, Cervantes describes the reality of his own province in an attempt to annihilate the chivalrous novel. Therefore, the main difference between the two resides in the manner of referring to places and times.

The timing must have been precise in order to set the stage for the events that would follow, for Borges’s work was not translated into English until 1962. Two years later, the American philosopher and art critic Arthur Danto would first see Andy Warhol’s Brillo Box 2 installation at Stable Gallery in New York. Confronting the issue of the indiscernible 3, Danto rethinks the art object in Plato’s terms (imitative theory) and moves beyond the dominating aesthetic — precisely the one I was assimilating when I came across the case of Menard/Cervantes — and theorizes a philosophy of art that necessarily has to reconceive the object starting with its ontological nature. The indiscernible could not be confined to a merely perceptual nature. It even went beyond the formal differences between Warhol’s Brillo Box and the supermarket version designed by James Harvey. The point was that such differences were no longer only confined to figurative art. Again, credit goes to Borges, who dealt with this dilemma outside the realm of art, and, even before that, to Marcel Duchamp, who signed a urinal “R. Mutt,” not to apologize for the ordinary but to explore the boundaries of art.

In the case of Menard/Cervantes, Danto distinguishes the concept of the “copy” from that of “appropriation.” The copy is what replaces the original, inheriting its structure and its relationship to the world. The appropriation, on the other hand, despite lacking some features of what it replaces, displays something that has such features. Moreover, the appropriation has a semantic structure and does not merely display the original in quotes. It has its own identity, which resides in the subtle matter of exactness: not being the result of an attempt to copy, the quotation develops its own meaning.

In other words, it is the concept of appropriation that Douglas Crimp begins to unpack in the catalogue essay for his 1977 exhibition “Pictures” when he describes Shoe Sale (1977), a sale of seventy-five pairs of shoes organized by Sherrie Levine at the Mercer Street Store in New York:

Levine had bought them from a job lot in California, and sold them all at a slight profit in a single day. This latter fact adds to the mystery of the event, for these shoes were certainly not useful to their purchasers, nor were they particularly attractive, and they seemed singularly devoid of aesthetic interest. Were they intended as a latter-day species of Duchampian readymade? Or fetishistic objects of a Surrealist kind? Or was Levine’s statement simply “Here are seventy-five pairs of little shoes”? But isn’t it precisely the impossibility of accepting that statement, a statement that is merely an indication of presence, that opens the way to signification?” 4

An “indicator of presence”: perhaps this helps define the appropriation practice that Levine developed as part of her theory of the postmodern. In the late 1970s, reality, history, and art itself were reduced to a contemporaneous present made up of commodified, superimposable images. Art productions were characterized by fragmentation and image repetition, undermining concepts like authorship and originality. The evident enlargement of the formal field of operation, now predisposed to nontraditional techniques and the production of new media practices via video and photography, was aimed at the dematerialization of the artwork. Appropriation thus became a quasi-theft that took possession of something a previous culture had produced. It functioned as a process of rewriting something that had already been formulated while at the same time investing it with a new aura.

Danto distinguishes between use and mention. On the one hand, an image is mentioned when it shows itself as an image contained in another image. On the other hand, mention is mainly used in pictorial representations, in the same way that style is integral to a work’s meaning. Mention is closely related to “transfiguration,” which acts upon the object and gives it a further meaning, taking possession of it and constructing it as another artwork. This manner of working resembles the mechanism of metaphor: it takes models and makes them “representational vehicles.”

The distinction between use and mention inevitably brings me back to Levine’s work, which immediately made me understand the case of Menard/Cervantes. The artist freely propagates icons of modern art, proposing them again without any evident formal difference or variation, such that it is difficult to distinguish between what is original and what is a conceptual appropriation. In many cases the difference lies in the works’ title, in the use of the word “after.” Levine literally reproduces other people’s images: photographs by Edward Weston, Alexander Rodchenko, and Walker Evans; drawings by Willem de Kooning, Egon Schiele, and Kazimir Malevich; and even Monet’s studies of cathedrals. In 1980, Levine worked on a series of photos that Weston had taken in 1925 that depicted his son Neil, bare-chested, framed from the waist up. By appropriating these pictures, Levine challenged the stature of the creator; she extended the presumption of originality to which Weston, as the creator of his images, thought he had the sole right. Weston, whose photography is very evocative, saw the absoluteness of his shots as something similar to the sculptures of Brancusi. Yet Weston’s images arguably exploited the naked body of his son to evoke a classical Greek myth of masculinity as filtered by subsequent cultures. Thus, Weston’s work already revealed the author himself as a filter for multiple manifestations. Levine’s untitled (After Edward Weston I) (1980) not only appropriates Weston’s authorship, already drawn from a long series of art traditions, but also suggests a cynically irony about the figure of the photographer as the demiurge of his own images. As a consequence, Levine aims to unmask the aesthetic original by pushing herself beyond, toward a demystification of the author’s originality by means of the photographic medium.

Howard Singerman in Art History, After Sherrie Levine 5 interprets Walker Evans’s Farm Security Administration images as appropriated by Levine in accordance with major postmodern critics, including Rosalind Krauss, Douglas Crimp, and Craig Owens. In other words, Singerman highlights the fact that Evans’s pictures are closely related to the literature of Borges and to the writings of Roland Barthes, 6both providing the necessary tools for understanding the practice of appropriation. After all, the author’s death and its consequences are the main themes of the works that built the foundations of postmodern critical thought.

In her practice Levine pursues demystification, achieving it in her work and in the object itself. It is a continuous echo that reverberates throughout modernism and the male conceits that govern the world of art. In Fountain (Buddha) (1996), the molten bronze object is invested with an erotic fascination that suggests a translation of Levine’s own emotional resonance. The artist “presents” the presence of images; such duplicity is evident in the twenty-two photographic reproductions of photos by Walker Evans: Untitled (After Walker Evans) (1981). The new images no longer represent the men and women portrayed during the Great Depression, but the images of those subjects that we recognize through their cultural representation.

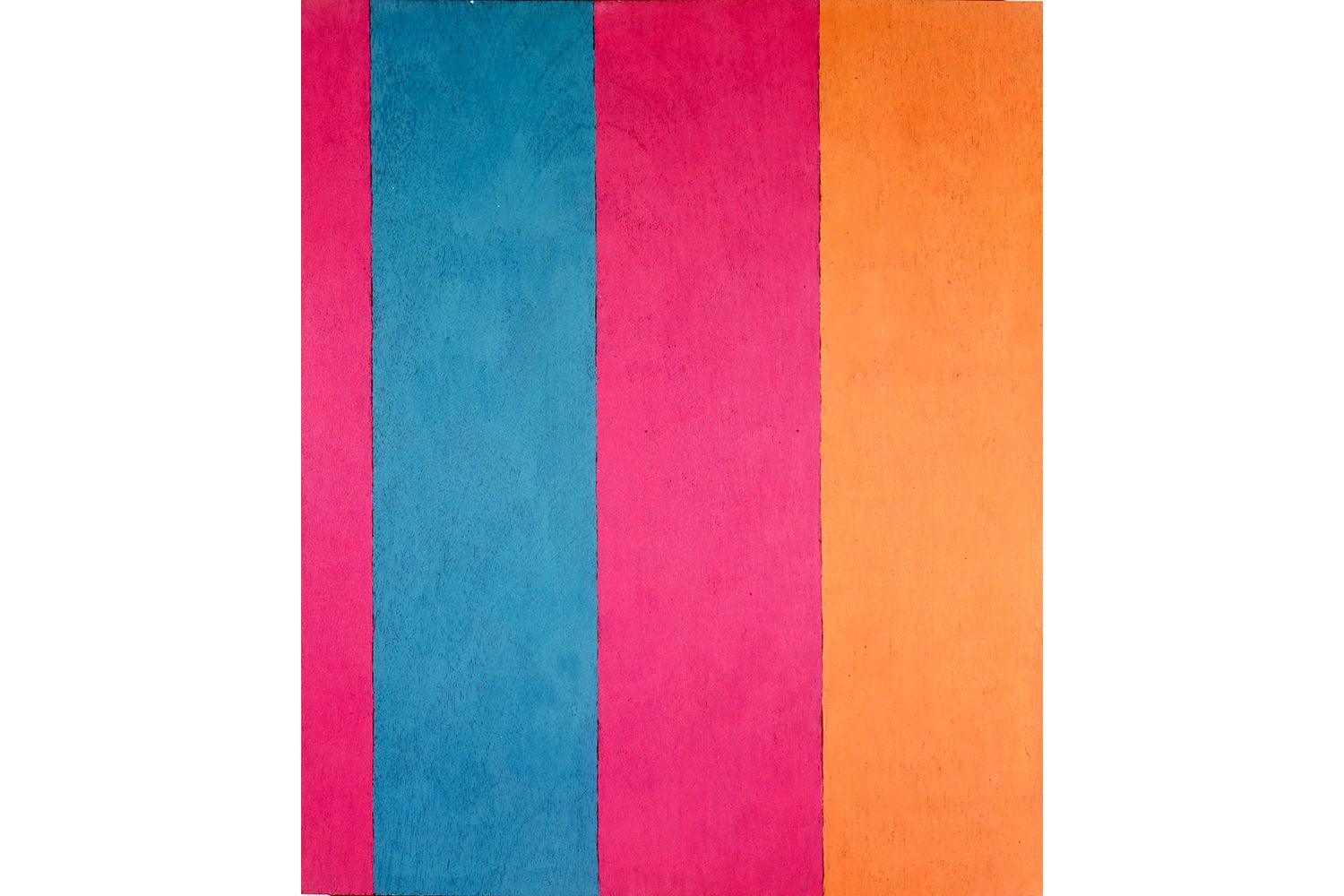

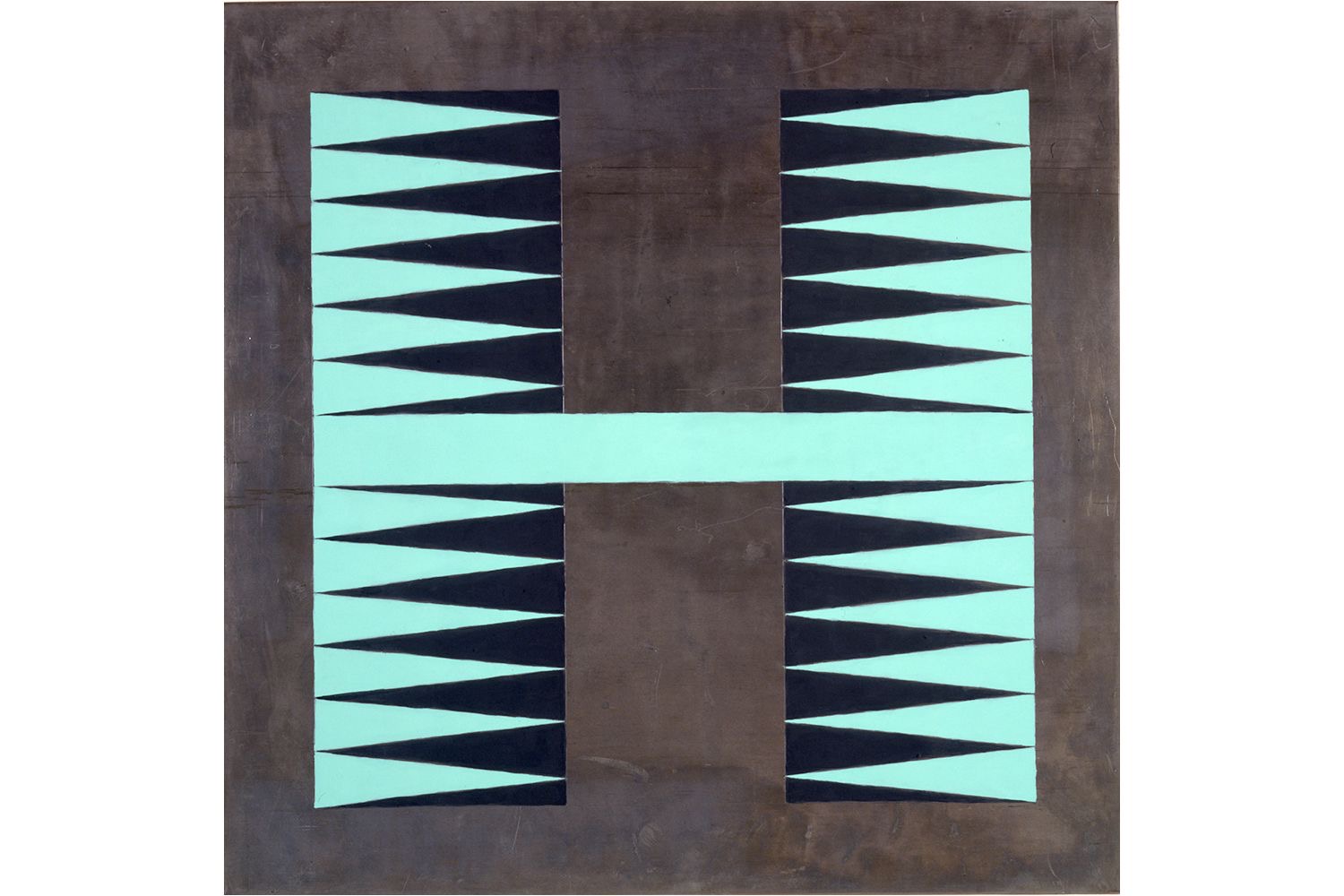

In the mid-1980s, following the advent of neo-geo, Levine appropriated various models of abstraction. Her “Broad Stripe” paintings from 1985, featuring large stripes and bright chessboards, reference the abstraction of painters like Frank Stella and Robert Ryman. Mechanically constructed and painted in shiny, sometimes kitschy hues, they translate a concept of abstraction without being able to obtain it, as if to replace the promise of a pictorial pureness and formal research with insufficiency and systematic failure. Similarly, her “Knot” paintings (begun in 1985), a series of wooden paintings featuring mechanically arranged knots, far from representing biomorphic or random themes, are intended to deride the alleged freedom of abstraction. These two series make fun of the same modernist abstraction that allowed Levine to approach the world of design, of kitsch, of spaces systematically excluded from that type of research. 7

Levine’s work, apparently well inscribed in the philosophy of art embraced by Danto, can be seen as part of the same essentialist vision of the art object that brings us to consider conditions external to the artwork, why it exists and why we recognize it as such — its aboutness. 8 In a review of Levine’s 2011 survey “Mayhem” at the Whitney Museum, Jerry Saltz wrote: “Levine once said her work is just ‘questions — that’s all.’” 9

And like every attempt to define the object of art, Levine’s discourse is one that “still needs to happen.” 10