Exploring issues of race and masculinity, Shaun Leonardo’s multimedia practice exposes and redresses the white supremacist power structures that oppress and violate Black and brown bodies. In visual and performance works alike, the artist foregoes the trauma porn that has long shaped such subjects, employing conflict resolution, dialogue, and empathy instead.

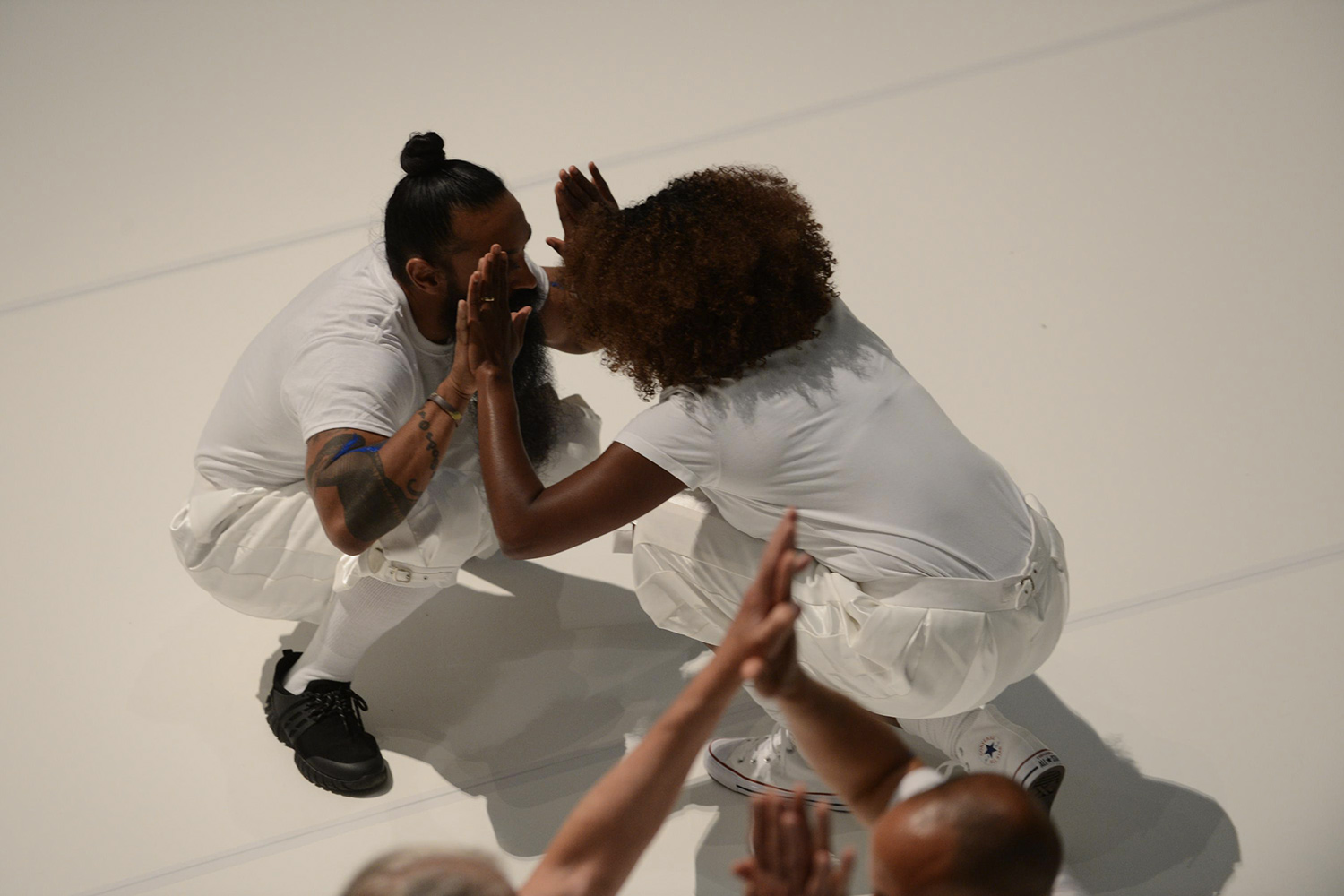

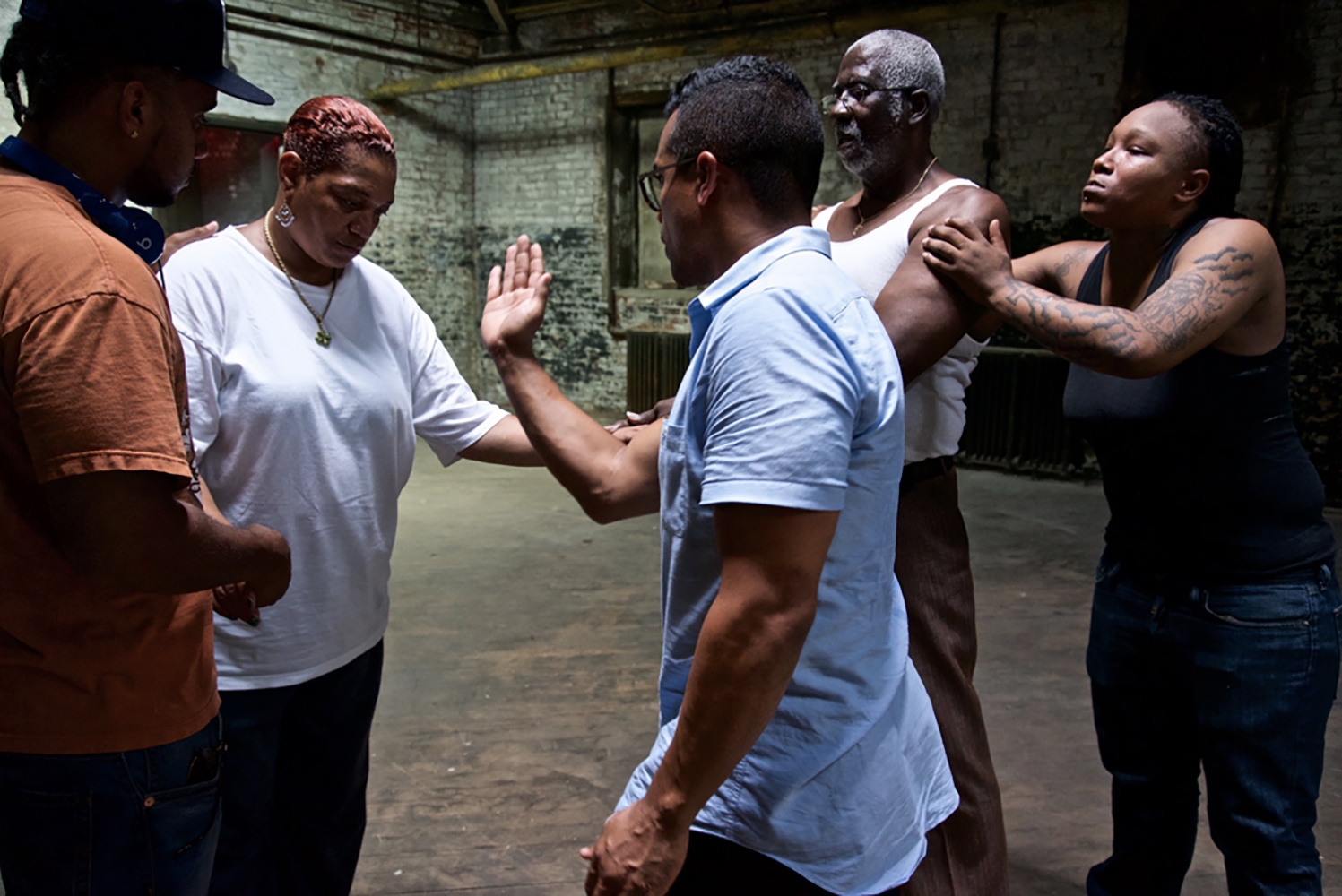

Whether bringing together people with opposing views on gun control (Primitive Games, 2018), conducting self-defense workshops (I Can’t Breathe, 2014–17), or acting as lead educator for an artist-led program for court-involved youth (Recess, 2017–ongoing), his commitment to community activism and outreach has been widely acclaimed.

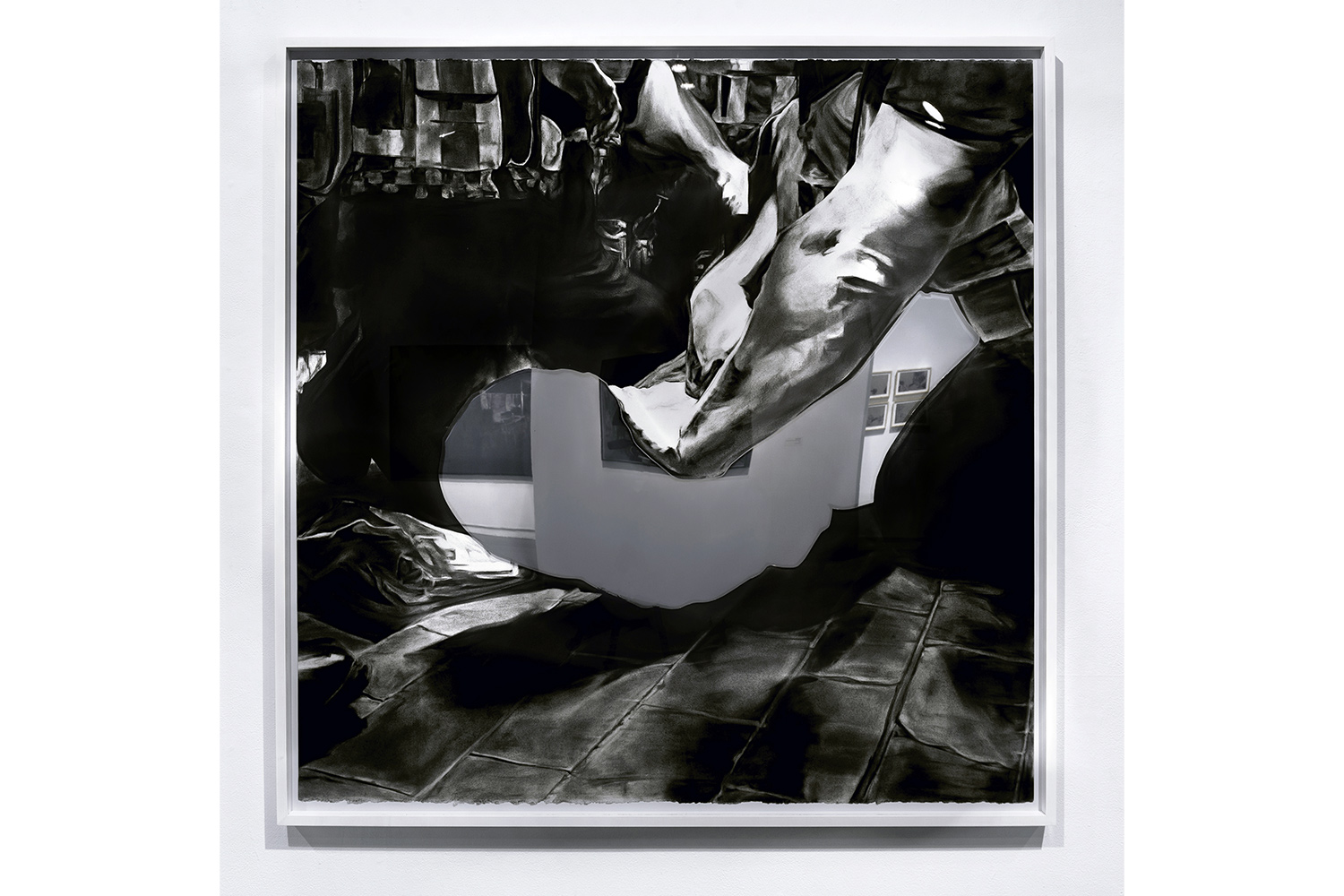

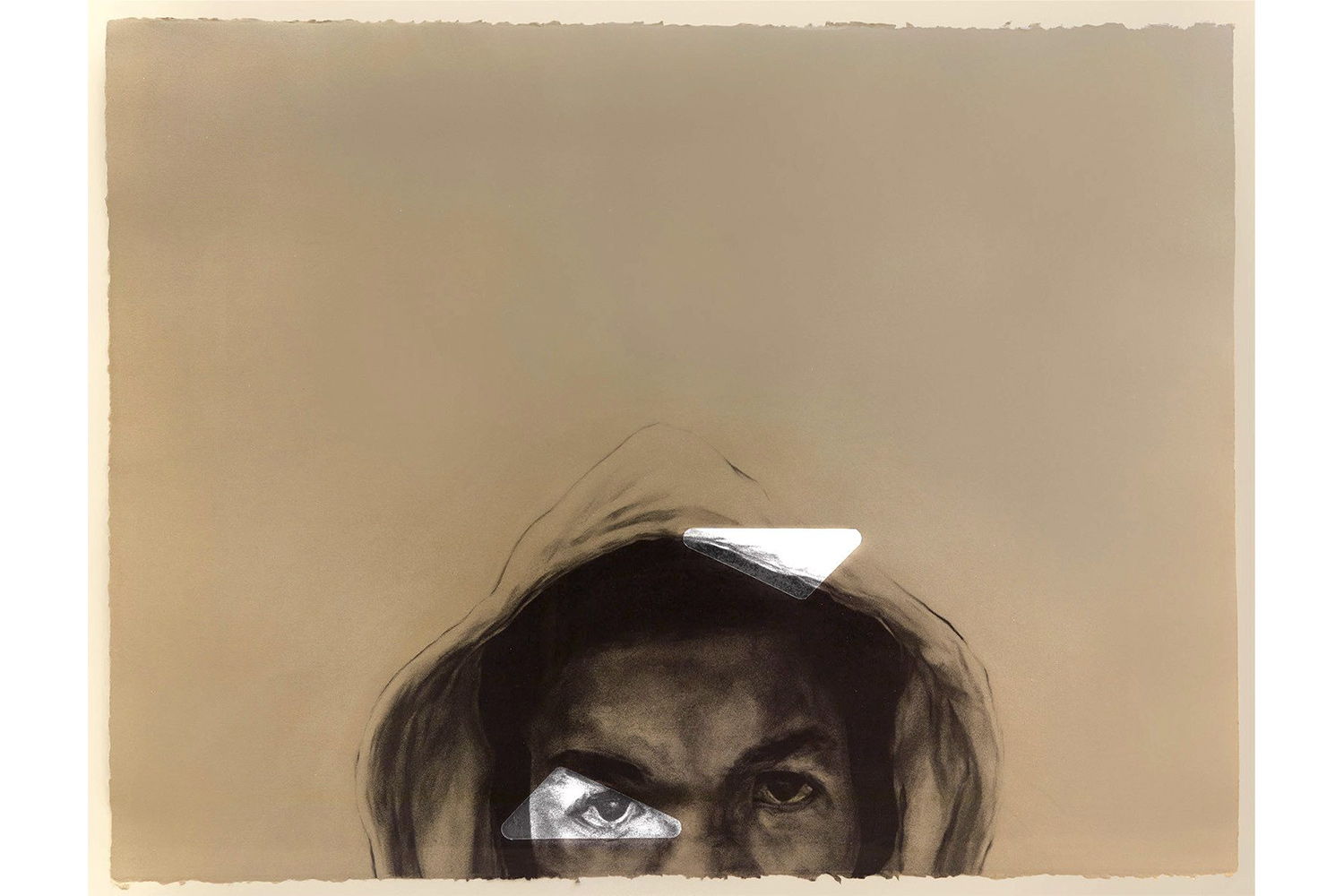

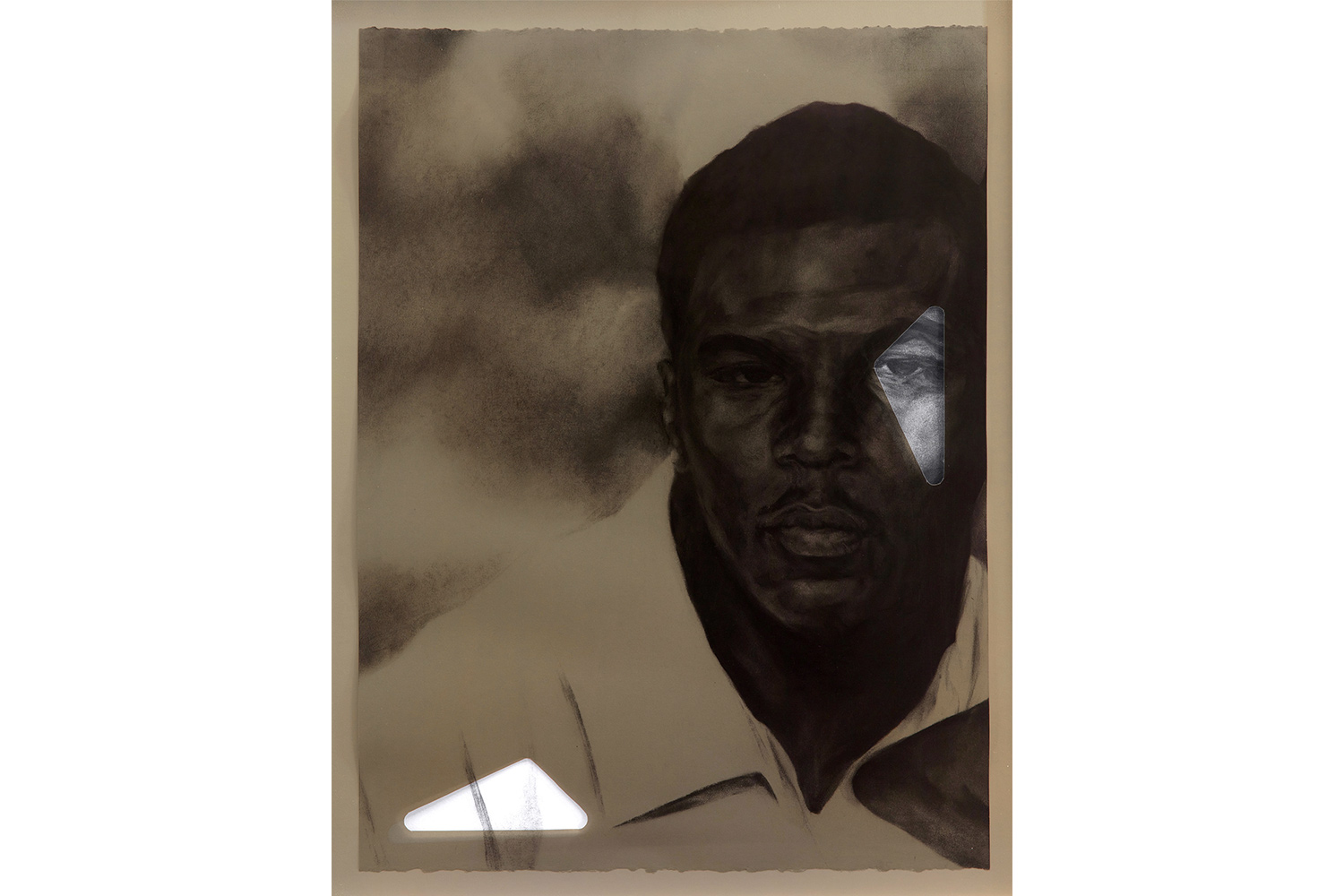

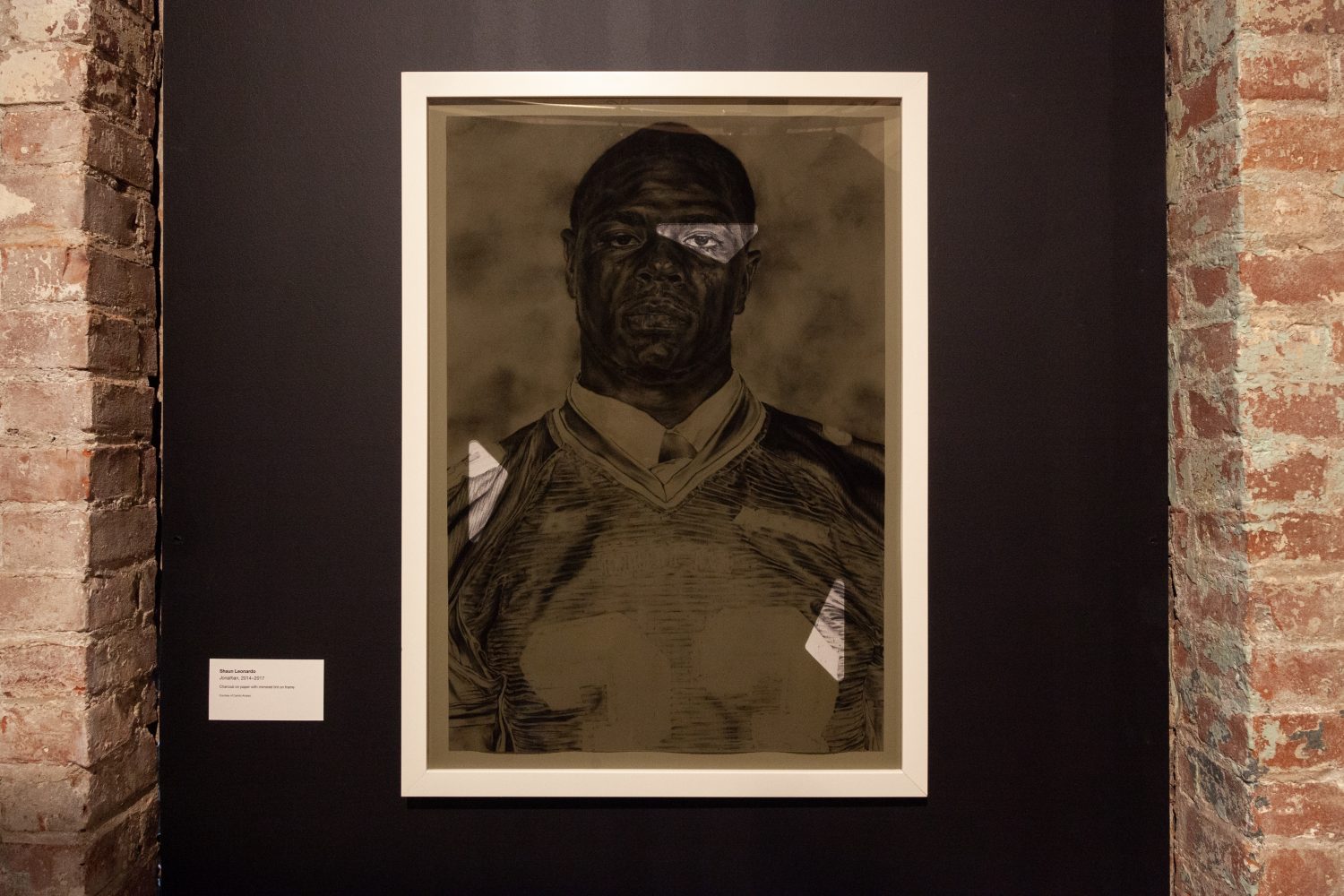

The viewer as participant, willing or unwilling but always complicit, remains central to everything Leonardo does. His traveling exhibition “The Breath of Empty Space,” which features charcoal drawings that break down and reconfigure — conceptually and literally — widely disseminated images of police violence, for example, foregrounds the act of looking. Designed to get us to consider the media’s role in shaping how we think, react, and behave, the paradoxical power of such imagery — used to fuel the media’s ongoing spectacle of Black death, and last summer’s historic Black Lives Matter protests — is endemic to this process.

And so is its treachery, a fact that became particularly evident when the Cleveland Museum of Art, slated to host the exhibition last June, cancelled it in the aftermath of community objections. Rather than engage those concerned in a productive discussion with the artist (whose very mission is to create such conversations) around the work’s true intentions, the institution caved in to the pressure. When MASS MoCA stepped in to take the show, I sat down with Leonardo to talk about the work and its thorny, powerful implications about systemic injustice.

Jane Ursula Harris: The title of your exhibition invokes Eric Garner’s last words, “I can’t breathe,” now a familiar rallying cry in the protest movement against police brutality. It’s also a quote from Friedrich Nietzsche’s Parable of the Madman (1882). What’s the relevance of the latter for you in this body of work, and how do the two references interrelate?

Shaun Leonardo: Let me offer some words here from John Chaich, the independent curator of the exhibition:

Responding to the formal and conceptual use of negative space in Shaun’s work, I recalled the Nietzsche passage, “Do we not feel the breath of empty space.” I could not help but also hear the last words of Eric Garner, “I can’t breathe,” which he uttered eleven times before his death, while in a chokehold applied by Officer Daniel Pantaleo. I was reminded of scholar Stephen Kern’s description of a “positive negative space” where the “background itself is a positive element of equal importance with all others.” Kern directs us to the substance in the absence of visual information. The empty space in these drawings — heightened by blurring, reframing, and isolating visual information — is activated when viewers fill in the blanks, reframe details, and remix narratives based on both personal experience and perceptions ingrained by media and cultural biases.

Its real resonance today, for me, lies in George Floyd’s utterance of “I can’t breathe” as we witnessed what felt like his execution — the life slowly leaving his body as he struggled underneath the knee of Officer Derek Chauvin. The continued relevance of that phrase is heart-wrenching, but reminds both me and the viewer that there is a long legacy to police violence, which extends well beyond this moment we are experiencing. One thing I hope this exhibition traces is the interconnection of these tragedies — the layers of systemic violence that all stem from how we, as Black and brown bodies, are seen and unseen.

JUH: You began this body of work as a way to process the 2012 death of Trayvon Martin in “personal terms… outside the media noise” that continues to exploit the visual spectacle of Black death for sensational ends. How has your chosen medium of charcoal enabled you to do so?

SL: Drawing affords a slow, contemplative grappling with the image for me, and, I would argue, the viewer. It’s in the deliberate, painstaking crafting of an image that we absorb the information differently — in ways that the moving image does not offer. It’s the very act of drawing that also gives me the time and space to make decisions — my application being additive in nature — training the viewer’s eye on information that would otherwise be lost or omitted by our selective seeing. It’s the depth of drawing — the density of the charcoal and breath of space both literally and metaphorically carved into the image — that allows us to sit with the hurt, and where, I argue, our looking is turned into bearing witness.

And to witness is to say to oneself that the image will not leave you. To witness dictates that you will seek healing through — not beyond — the struggle. To witness means to internalize in such a way that the very manner in which we look and act everyday is questioned.

JUH: The sequential format you use breaks down headline images of police violence, particularly those repeatedly circulated by the media — Rodney King being beaten in the street, Eric Garner in a chokehold — into multiple viewpoints that reconstruct our relationship to them yet paradoxically refuse linear readings. Is this a way to counter the impact of mediated violence?

SL: Rather than “counter,” I would argue “question.” There is a direct correlation between the selection and dissemination of images by the media, the ways in which we receive those same images, and what is formed as a memory in our collective consciousness. The distraction and speed at which we are bombarded with a news cycle reduces these tragedies to mere headlines. The drawings allow me to work against this reduction and question the very manner in which we are complicit and complacent in our seeing.

In the Laquan McDonald work, for example, which consists of two drawings, we first see — in the haziness of dash cam footage — the dimly lit street lined with squad cars and the closest officer in aiming position. In the second, we see Laquan McDonald, hands at his side, alone in what could have been a corridor of stars. Read together, with the information of one scene separated into two frames, we perceive the distance at which he was deemed a threat. In the Eric Garner series, we see the same video still replicated across six stacked drawings, each emphasizing different types of information.

JUH: And this serves to slow down the viewer’s reception?

SL: Correct. A viewer then spends time looking at the storefronts or tree-lined street — a space that was familiar to Mr. Garner but that becomes an arena of violence.

We may consider why we never took the time, real time, to study the gesture of his hands, which he made in an attempt to pacify the confronting officers.

Or question whether we ever truly examined the officers’ aggression and chokehold maneuver — the very first course of action undertaken once Eric Garner is deemed a threat. In the Rodney King drawing we see the iconic video still of his beating, but with a void where his body would be.

JUH: How does that void function for you?

SL: As a refusal to present his Black body in the way we have been ingrained by the media to see it… in its punished state. More often than not when we recollect this image, we only recall the two officers making contact with their kicks and batons. Is there any accident then, that to this day, in the headlines we will only read about the four officers charged and acquitted?

JUH: And the use of dark mirrored tint in the work?

SL: It forces the viewer to not only watch themselves watching, implicating our once passive seeing, but also explicitly call out the way in which, in our collective memory, we dismiss, or maybe forget, the fact that there were eleven officers at that scene — all of whom deemed Rodney King a threat even as he lay on the ground near paralyzed. All of whom should have been held culpable.

JUH: Are you also indicting our obsession with violence, even if we condemn the police brutality associated with these deaths?

SL: Well, I believe the condemnation is short-lived, particularly amongst many white citizens.

It’s in this slowed, deliberate looking these drawings offer that we are reminded that in these scenes of murder, these Black and brown citizens were rendered less than human well before shots were fired, a chokehold was placed, or a baton was swung. It’s in the information that I reconfigure — what was once watched with speed, commotion, and passivity — that we perceive the fear of the Black and brown body that police carry within their bodies and psyches, which then directly leads to our deaths.

JUH: And the ultimate message then to your viewers is?

SL: It’s in what we choose to selectively see and not see in the media images and footage that we become complicit in how each of these murders is swept away as a statistic, and also complacent in not addressing our own fears.

JUH: Our unexamined fears of Black and brown bodies you mean?

SL: Absolutely. And for Black and brown viewers there is another offering. Just as I required for myself when I stared into Trayvon’s eyes, we must have the time and peace to reckon with these images of death differently. In the quiet of bearing witness we are afforded the space to internalize these images even as they hurt us. I argue that to heal we must grapple with how the trauma is lodged in our bodies and psyches. These images will never just go away.

JUH: Your work has long explored the devastating impact of white supremacist patriarchy on Black and brown bodies, particularly notions of masculinity both projected and internalized. Can you talk more about how this body of work extends those concerns?

SL: It’s as I said before. We Americans have only begun to analyze how our entrenched definitions of Black and brown masculinities manifests into the continued control, containment, and removal of our bodies. We spend so much time, for example, debating the protocol or standards of policing that we rarely assess the embedded fear officers carry that will always lead to our murders.

It’s in this exhibition, but also in my performance practice and the work that I conduct in the sphere of criminal justice, that I wish to approach this fear — both as it is imposed on our bodies, but also as it is internalized from a young age, corrupting our sense of self.

JUH: In the video documenting your eponymous performance The Eulogy, also on view, you recite the searing yet rueful speech given by the nameless Black narrator in Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man — another literary touchstone — at the funeral of his dear friend Brother Tod Clifton, murdered by a white police officer. It’s a pivotal moment in the protagonist’s psychic development, one that unites the personal and political. In your transposition of Clifton’s name, repeated again and again, with the names of those lost to police violence, you underscore the same struggle to create a legacy for Black men beyond that of violence and trauma. Do you see progress being made?

SL: Thank you for that beautiful synopsis connecting my work to Ellison’s. Let me leave you with this: we exist in a moment of our history in which the complexity of our experiences has been flattened… whether by the sensationalism of headlines or polarized nature of our arguments. Our positionality, or more importantly, our ability to stay in the tensions and contradictions of our lived experiences, is being erased by our incessant need to protect our worldviews. But that is not life. We must always work through the ugliness and maintain our presence. So I don’t spend time thinking of progress. I contemplate what is needed of me and for the people I care about. Remembering is one aspect of that need… never allowing these names and lives to be buried by history. Instead we breathe life into this history of violence and death, giving this past a meaning by how we act in the present.