Combining an impressive range of imagery drawn from YouTube, reality television, music videos, cartoons, documentary footage, and self-crafted animations, the prodigious work of New York–based Moroccan artist Meriem Bennani encapsulates all that is fantastic and strange about our contemporary digital landscape. Amid the soft collision of bodies, architectures, and visual languages that make up Bennani’s immersive installations are poignant narratives that approach intricate social and political issues — from postcolonialism to nationalism to the current immigration and refugee crisis — with astounding insight and levity.

Here, Bennani discusses her two most recent projects, Party on the CAPS (2018), a work first commissioned in 2018 for the Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement in Geneva, and Mission Teens: French School in Morocco (2019), a multimedia installation currently on view at the 2019 Whitney Biennial.

Olivian Cha: How did you first conceive of the story for Party on the CAPS (2018)?

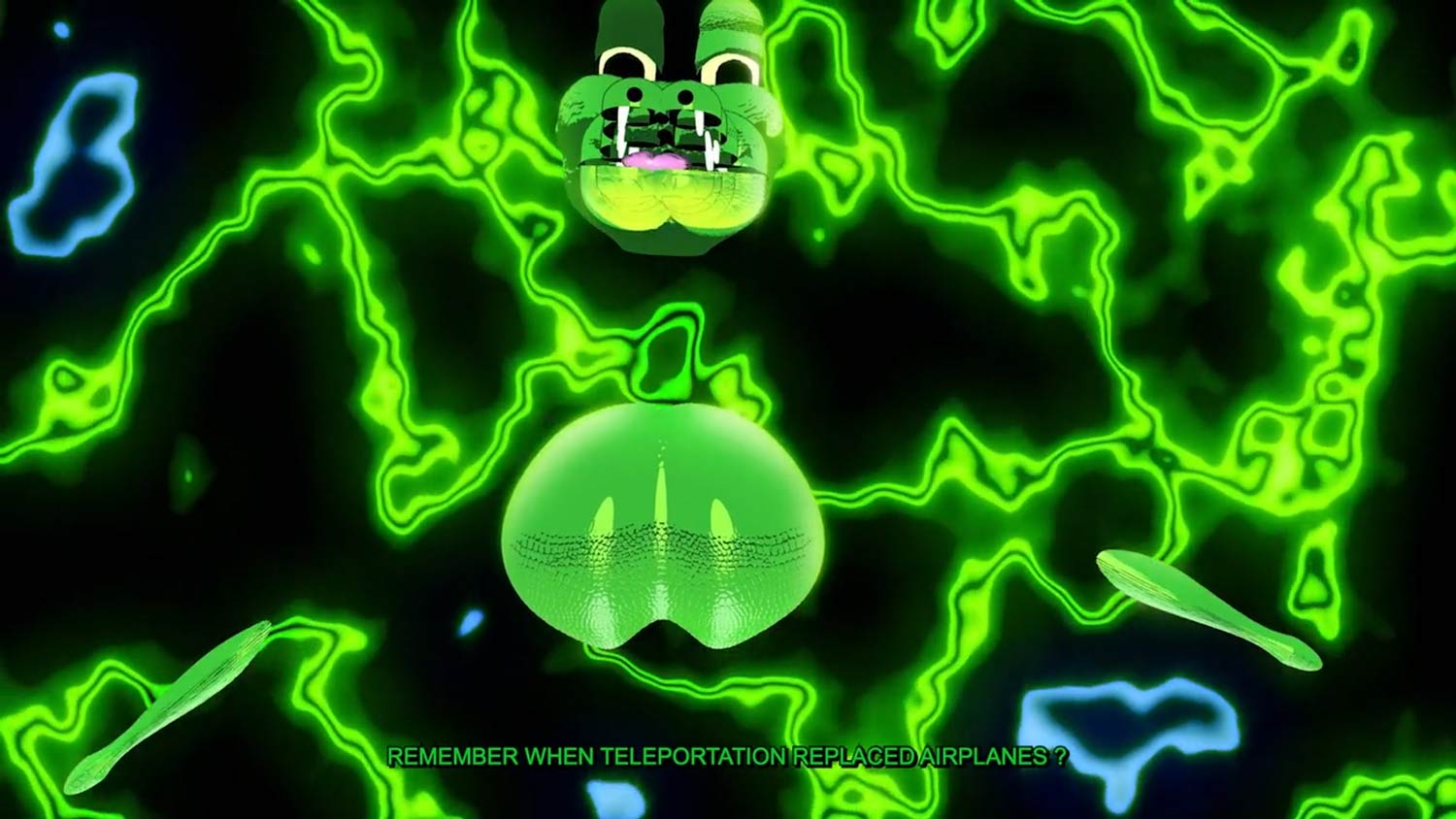

Meriem Bennani: The idea came to me while I was conducting research between projects. I became deeply interested in the idea of teleportation, not only as a sci-fi trope but also as a real goal for modern science. This was also around the time of the refugee crisis and shortly after Trump was elected. I began to wonder what would happen if teleportation were possible, and immediately imagined America and Europe doubling up on immigration and customs policies in order to manage all the incoming teleportation.

I envisioned the CAPS as a kind of temporary holding area — an island somewhere in the middle of the Atlantic where the intercepted teleporters had to wait to gain entry. It would require such a long bureaucratic process that the population would keep growing to include subsequent generations of residents from all over the world. Morocco had just reentered the African Union, and I chose to focus on African diasporas. I was also interested in Morocco’s relationship to its Africanness, which is too often disregarded in favor of its belonging to the Arab world. I thought the best way to represent this place was through a documentary. What would life be like on the CAPS? I decided to feature the Moroccan neighborhood of the island first (I am working on a second chapter that will take place in other African countries) and shot all of the footage in Morocco, enlisting non-actors and family members currently living there to talk about it as if they left and could never return.

The CAPS, short for capsule, is also a physical analogy for the idea of diaspora. The island is comprised of residents who exist in an in-between state, both physically and psychically. They are neither in America or their respective homelands.

OC: Besides the central theme of teleportation, the video also features minor narrative threads that seem to frame immigrant bodies as sites of physical displacement in extremely fraught ways. For instance, what is “plastic face syndrome”?

MB: During my teleportation research, I was also reading a lot about biotechnology. Today we have the ability to analyze DNA and conduct reverse aging in mice. In the future of the CAPS, people would have more agency over aging and gender. Age reversal would be a part of everyday life. With “plastic face syndrome,” I was also imagining the side effects of a population that has undergone teleportation interceptions. This physical trauma would manifest in absurd ways, as shiny, plastic, liquid faces. Although the effects are the result of violence surfacing on the body on a cellular level, they are treated as minor health problems, like skin blemishes. These traumas are what ultimately unite all the different communities on the CAPS.

OC: Is this related to “babycouple adults,” which are represented early in the video through footage of two toddlers on a motorbike?

MB: Babycouple adults are essentially adults who choose to occupy the bodies of babies. My world of the CAPS is partially inspired by that video, which I found on YouTube. There is something so strange and surreal happening in that moment. I kept asking myself: What is this? How did this happen? I think they are riding down a street in Morocco, because there is this Moroccan red taxi in the background, but it’s hard to know exactly.

OC: We all receive cultural content from YouTube, but often there is no sense of authorship or geographic specificity. Images sort of float around in the ether as material.

MB: Yes, everything becomes collage. I didn’t invent the aesthetics of the CAPS; they are largely derived from a collection of YouTube videos. A large part of my practice involves watching these videos and organizing them into archives. I’m obsessed with them! My favorite ones are always when something amazing happens but the moment is filmed in a casual way — it feels even more surreal somehow.

OC: How important are the sculptural aspects and installations that frame your videos? Do you ever feel that contemporary artists are under pressure by museums or commercial galleries — and even social media — to create more spectacle-driven experiences for displaying video?

MB: I don’t view it that way at all. A lot of artists still make videos and successfully project them in a black box. I think the reason why I want to be in the art world and not the cinema world is because there is more freedom in how I am able to frame my films. Everything from the origin of an idea to filming to editing can all be extremely intentional. Making decisions surrounding the physical installation and presentation of my videos is a critical step in the production of my work.

There is also the simple fact that by creating the frameworks that host my films, I somehow tricked myself into making sculpture, which I never thought I’d be interested in. I make all my objects in 3-D programs; when they are fabricated and I finally get to see them it is an incredible thing. I spend so much time on the computer. It feels like that’s my destiny. Shooting video is only ten percent of the production, and the rest of the time I am just attached to my screen. Video and cinema are so focused on the eyes and the processing of information through visual means. When you can walk inside a video installation it turns the image into an environment and becomes a more physical experience. Installations also allow me to add a dimensional aspect or axis to the videos. There’s more room for play. The work isn’t real for me until it’s installed in the gallery. Before that it’s all imagination — there is no gravity.

OC: That makes me think of the Wile E. Coyote image you posted on Instagram during your installation of Mission Teens: French School in Morocco (2019) at the Whitney. The Looney Tunes universe seems like a fitting counterpart for how representations of space are articulated in many of your videos.

MB: Well, one of the benches in the installation was based on that image. But I have always been drawn to animation. Physicality doesn’t have the same rules in cartoons. Everything is always subjected to the progression of the story, or the joke. The images have their own logic, which has nothing to do with the real world.

OC: Like the singing home facades in Neighborhood Goggles (2019). Can you tell me a little bit about this second video and its relationship to Mission Teens?

MB: I was interested in exploring larger questions of power and postcolonial relations through the more intimate social relations of high school teenagers. Neighborhood Goggles depicts the houses where some of these teenagers grew up, where I also grew up. I asked Lil Patty, the same rapper featured in The CAPS, to write a story about what these homes might say about themselves. He made the accompanying songs while I animated the architecture. The work is shown in a dual-screen sculpture meant for two viewers. While one screen is playing the video, the other screen displays the text “Press button to start.” But if you press the button the other screen turns off. Viewers quickly realize that they have to deal with the person on the other side in order to share the work.

OC: The tension of sharing space is also present in the video, especially during your interviews. I am thinking of a particularly poignant moment when one of the main characters in Mission Teens is performing his wealth in a very ostentatious way, and we suddenly get a glimpse of your animated donkey avatar as a reflection in his sunglasses. Why did you decide to insert yourself in that moment?

MB: It wasn’t a reflection in a literal way. I was a very different kind of teenager, but it certainly was the heaviest moment in the film. It was a very long scene and I needed to cut it with something, to break it down so it didn’t lose its steam. I could have animated one of the objects in his room, but what he was saying was so extreme that I thought any intervention might be read as judgmental or in bad taste. Instead, I decided to let him be and to connect the viewer with my situation as the interviewer behind the camera. It was a way to check myself, to remind the audience that I am there, but also that you, the viewer, are there.

OC: When certain emotions are so palpable or awkward, they become impossible to process in their raw state.

MB: Yes, I literally had to take a step back. The shot was so tight and I wished there was more space between us. The reflection in his glasses allowed me to find that distance. But I don’t dislike him. He is endearing and it’s obvious he is trying to shock us. I believe much of what he is saying is just a consequence of his upbringing, of a specific education and class. In a way, he is more honest than others who might feel the same way but don’t expressly vocalize it. That’s why I like him so much as a character — he is able to articulate some of the more extreme views and problematic subtexts within Moroccan culture. Yet there is also complexity in his perspective.

OC: It was so important for him to put on a show. I found myself asking whether he was performing for you, or Hollywood, or some abstract Moroccan spectator, which also led me to think about the reception of your work and your audience. Who is your audience?

MB: It’s really important to me that anyone, whatever their background, their relationship to art or their political views, can view my art. Otherwise, I don’t really see the point. At the same time, I am always wary of making culturally specific works that carry the burden of explanation. When an artwork comes from outside the dominant Western culture, the artist is often charged with the work of translation. I’m not interested in that kind of labor. Instead, in a work like Mission Teens — which touches on the postcolonial relationship between Morocco and France — I try to emphasize broader ideas surrounding relationships of power and the nuances of those dynamics. Or, when I am making a project like The CAPS, there are elements of performance and fiction that I believe to be universal, as they function and resonate beyond the given context. That is why cinema is so beautiful; you can watch a movie about someone so removed from anything you know, yet having access to their emotional state allows you to form a connection with them.