Courtesy Maureen Paley, London.

Catherine Wood: Your recent work refers to or features images of men from political organizations in the ’60s and ’70s (such as Lotta Continua). What is it about those groups, and the images they created, that you would have seen in the media that attracted you to appropriating them?

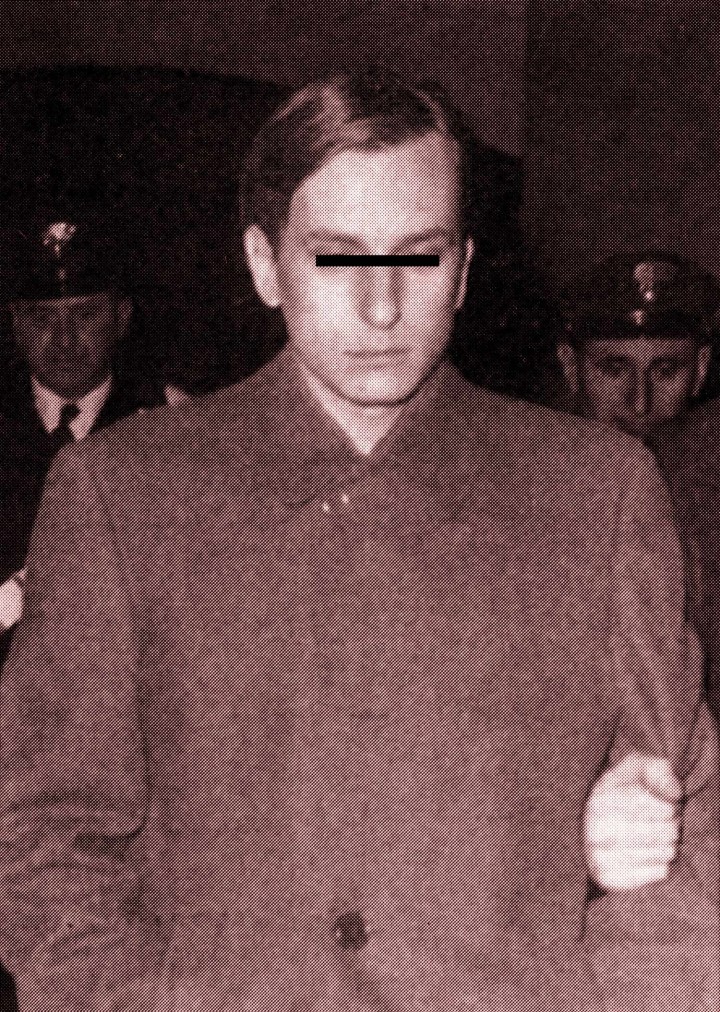

Seb Patane: What attracts me about these organizations is their conscious decision to operate in a political field yet using a strong visual component. The Lotta Continua founders for instance described their modus operandi as ‘violenza d’avanguardia’ (violence of the avant-garde) thus lining themselves along ideas of a specific kind of performativity. They had a definite visual identity that they exploited to achieve their extreme political goals. Some of these images eventually became historically iconic, for instance the image of Italian politician Aldo Moro, kidnapped by the Red Brigades and photographed in front of a banner depicting a pentagram, a symbol they had adopted. It is an image that is burnt forever into my subconsciousness and I am sure in that of many Italians.

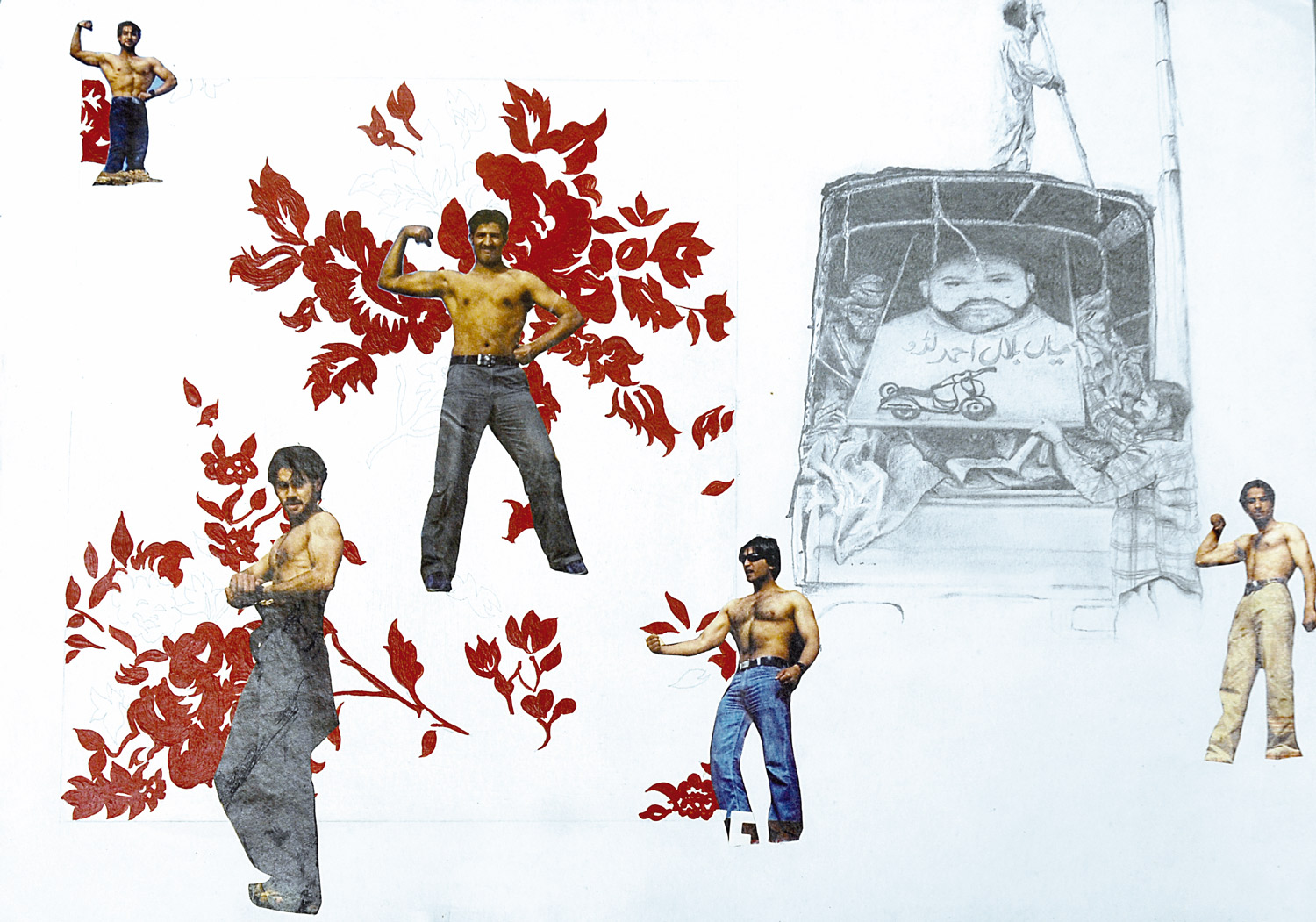

CW: How does the ‘aesthetic’ aspect of those protest movements relate to your practice as an artist?

SP: It’s an appropriation that I like to make in order to suggest ideas that question the power of so-called political artwork. Some of the kind of visual choices adopted by those protest groups like banners or the use of what I call anti-portrait seemed to relate to issues I am somehow trying to address myself in some of my pieces.

To be precise, I never really set up to be explicitly political, in fact my approach to those issues is almost one of a ‘lazy learner.’ Through researching the visual iconography of those revolutionary years, I started getting closer to the motivations behind the need to make work, or indeed to propose a social statement that is trying to convey some sort of message, however successful or unsuccessful or constructive or destructive that very message may end up being.

CW: What is your relationship to the photographic image? You often use historic images and manipulate or obliterate them in some way, as though there’s a sense of violence towards them, that you feel compelled to partially destroy them?

SP: My initial attraction to these pictures is usually pretty visceral; what I mean is that I experience a kind of transport that is almost like a gut reaction. I suppose one could also say that there is already some kind of violence inherent in that relationship, but it’s more like my consciousness has been contaminated by that image.

Eventually, my interaction with those images is in fact an act of respect rather than subversion, but it feels like that as a reaction to that psychological violence the outcome ends up looking like a need for abstracted concealment of some sort, almost to balance out that sense of devotion towards the image. It’s a game of contradictions.

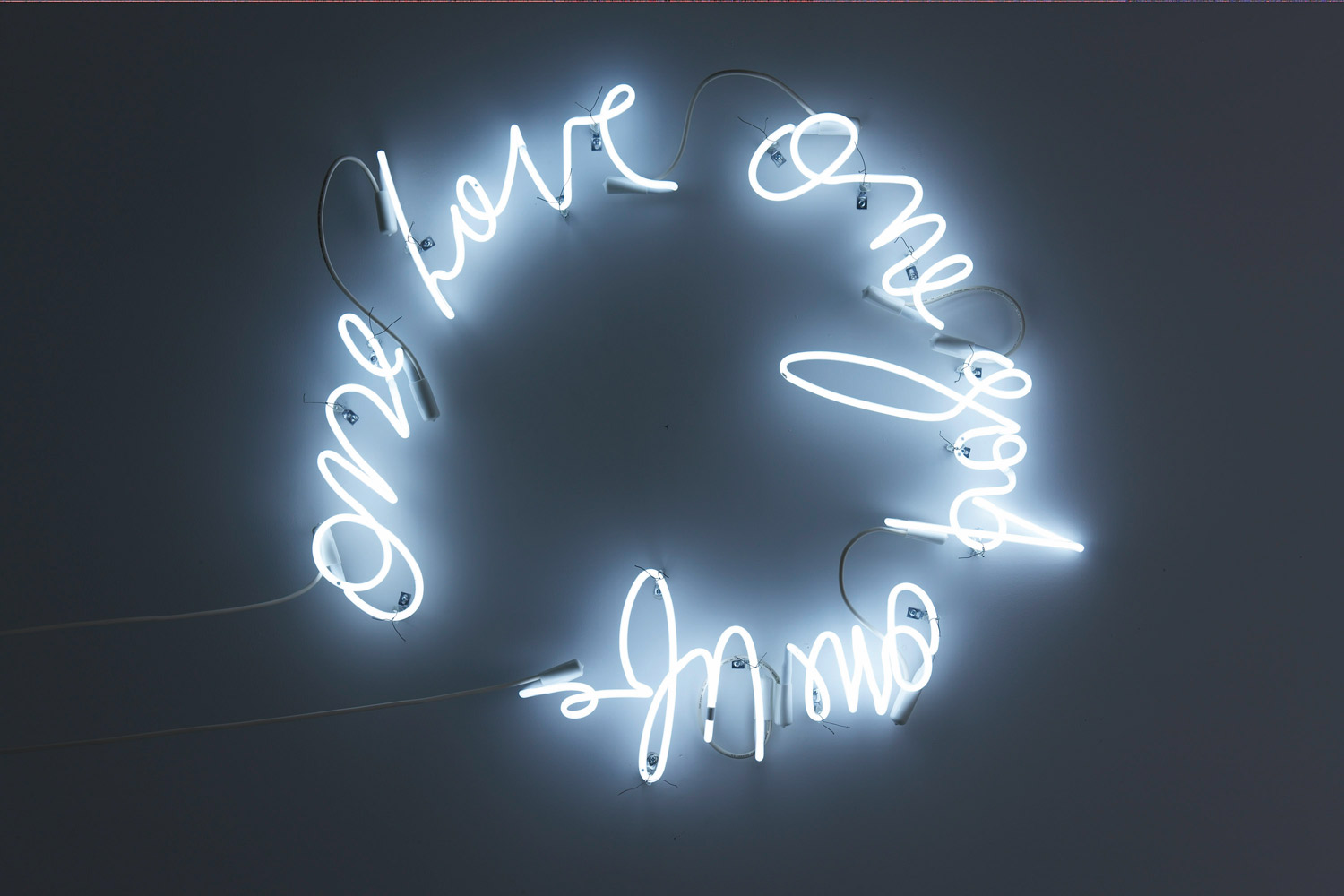

CW: Is there any parallel between how you see the use of these ‘out of control’ aspects such as the black biro effacements in the earlier drawings or the ‘censored’ marks in recent pictures with the introduction of music into the space?

SP: I guess it’s like a chain reaction. Because I often work within a very rigid framework — you know, the MDF panels, the tight spatial arrangements, the sparse feel of most of the installations — I eventually feel compelled to give things a different dynamic by introducing for instance sound, which by definition is intangible therefore volatile and more anarchic. Ironically I have ended up introducing that kind of censorship iconography you mentioned just to balance that in turn; the earlier drawings feel very organic and disordered, which coincidentally is a dynamic that seem to address a specific relation between anarchy and the organic described in some ’60s theories that I am reading about at the moment. But the censorship images have a sense of enclosed frustration about them… so it’s almost like a circle, starting with a very definite image that gets interfered with freely, then gets straightened out a bit… a constant shift.

CW: You ran a unique nightclub event called “Nerd” for some years, it seemed to me very much a part of your art practice in the way that it created a space for participation and performance by both artists and club-goers who were involved, with events such as Spartacus (formerly Lali) Chetwynd’s performance Thriller or artist DJs.

How was the creation of this social space for performing certain alternative identities related to the depiction of political movements in your work?

SP: “Nerd” felt like some sort of best kept secret. People who came made it their own and always used to say to me how much they enjoyed that feeling of community and exclusivity. There was something unique about the feeling that within that container anything could have happened, like when Spartacus proposed to perform her Thriller piece. That night at one particular point we filled the room with fake smoke and ‘zombies’ started appearing from all angles; people had absolutely no idea that this was going to happen so it felt really anarchic and out of control. I guess alternative political movements retain a similar agenda, like that uncontrollable, exhilarating feeling you get when you feel like you may be able to change the world, if only for a minute.

CW: Is there a link between your interest in contemporary subcultural ‘style’ and the secret/coded nature of these operations historically?

SP: I see those subcultures like providing society with something akin to an ongoing durational performance. It’s almost like secret agents, hidden performers acting within crowds to achieve a subtle sense of displacement. When I think about these ideas of rebellion, protest and revolution I actually never think about loud fights or violent wars, it’s more like a quiet but incisive time-based infiltration of consciousness.

CW: Could you say something about the ‘chain of references’ that links different aspects of your work in the last 5 years, and how you decide upon the found material that you appropriate?

SP: Well it all happens organically. I think it’s all part of the subconscious, of which I am a great believer. Although my work may appear aesthetically as very thought through, in fact most times I act in a very instinctive way. True, eventually this instinct is usually filtered very carefully but I am surprised as much as any viewer on how different aspects of the work end up relating to each other. I don’t set myself up to do only work that requires a found object, but sometimes I feel like we are inundated with so much visual stimuli that it’s almost a pollution of the eye. So I feel more inclined on re-using a great image that has been discarded or overlooked, almost as to give it a second chance.

CW: Do the simple geometric MDF structures that ‘stage’ the mise-en-scène of your installations have a relationship to minimalism, to Robert Morris for example? Do you intend a relationship to the physical presence of the viewer?

SP: No, I don’t feel there really are specific references to any particular artist, or not in the fine art area anyhow. At some stage in my practice I felt like I needed more solid structures to enable me to play around with the elements of my installations like the prints on canvas or the sound loops, so I started devising these simple MDF constructions that are just that tiny bit askew so don’t end up being too rigid. Because of my interest in theater design they are arranged almost as to enact the viewers to perform within them, by marginally negotiating their physical interaction around them.

But again, it’s a combination of the rigid with the unrefined that interests me and that I hope will create an interesting tension in the work.

CW: How does the mise-en-scène of the gallery installation relate to the drawn tableaux from Victorian theater magazines with which you have been fascinated, such as The Sketch? Is there an interest in the fictional potential offered by the space of theater? How is that grafted with your political interests?

SP: I guess it’s the potential in believing in ideas of ‘fakeness’ that I am fascinated by, a bit like theatrical or cinematic notions of ‘suspension of disbelief.’ As an artist, I try and put a lot of trust in the power of the image, which again is what a lot of political movements, especially those satellite ones, wanted to exploit.

My installations retain a rough if minimal theatrical aspect that leaves them vulnerable and therefore open to tougher inspection.

In a similar way, we can nowadays look at those aged images and interact with a contemporary knowledge that will challenge, in good and bad ways, the importance and validity of such images.

I like to think that fictional narrative can be a very powerful tool indeed, as it has the potential for real subversion; as viewers of anything visual we are put in a position to question reality, and that fragile moment when we doubt realness can be a very inspiring one indeed.

CW: There appears to be a ‘gothic’ aspect to the relationship between nature and culture, ‘live’ performance and sculptural ‘deadness’ and the uncanny quality of your biro drawings/ spinning figures in performance?

SP: What interested me for instance in the Victorian images was the sense of passivity that they retained, which I felt I was trying to challenge by introducing those automatic-like drawing interventions. What I like is the idea that fiction can interfere with reality, the ‘blurring of art and life’ if you like; psychologically there is something terrifying about the idea of the inanimate that then comes to life, which I guess is where a lot of theories about the gothic converge. I am attracted to the potential for a change in dynamic in anything that has a ‘live’ potential but that also poses itself as lifeless, however small and almost imperceptible that change may appear to be.

CW: Which artists historically have been important to you?

SP: Although I have artists who I admire I’m usually more likely to refer to creative people who act at the margin of the so-called fine art area. So I am more inspired by musicians like Coil or Current 93, or by all-round artistic figures like Alejandro Jodorowsky. I like how these people have a broad approach to the overall creation of a project, be it a record, or book, or film. It feels like the meaning behind their work can be transmitted via different levels, of which only one happens to be visual; I guess it’s again a bit like what those political movements we discussed earlier felt they were doing.