1996. A dimly lit table. A blacked-out television studio. The Charlie Rose Show. A talk show host and three young American novelists — still outsiders in the literary establishment: Jonathan Franzen, David Foster Wallace, and Mark Leyner. A discussion pertaining to the reception of their novels in the age of the “internet, information, and images.” An elephant in the room.

Packed into a fifteen-minute segment, the trio had been summoned to defend their craft. A defense of the novel on television is a battle between the neck and the sword. The anxiety articulated was not so much that the novel would be supplanted by television and the internet, but that the novel — especially their knotty, experimental, and demanding brand — would lose its license to agitate as institutions present more simple, seductive, and ultimately reductive alternatives to criticality.

Architecture is like the novel, but the specter threatening to supplant it is itself and the new world it aims to construct. The elephant in the room is anyone brave enough to say what the profession is or isn’t — in this case, it’s us and some students from SCI-Arc, Los Angeles, who claim that their beloved institution has become a shadow of its own reputation, is full of “institutional preservatives,” and feigns an appetite for agitation.

We borrowed the spirit of the nascent novelists on The Charlie Rose Show in 1996, who were disabusing themselves of the innocence about the profession they had committed to. In our discussion about architecture, suspicions arose about the “synthetic sense of unity” that it extols, so here they are, laid bare, from us who at this moment are still outsiders looking in, defending and critiquing that which doesn’t belong to us yet.

Manga Ngcobo: Would you introduce yourselves as perhaps a collective of people who share the same values and a particular concern?

Ari Diamond-Topelson: We’ve actually never really defined that. We have no shared authorship.

Reed Donaldson: I don’t think that any of us would consider us a collective, but I think within our school, we fit into some niche.

William Madsen: It could be read as a sharing of values, but we’re not actively coming together with an agenda. We’re just friends who talk.

MN I suppose friendship is as good a reason to refer to yourself as collective as any, but one thing you do have in common is that you are all students at SCI-Arc. I’m particularly interested in unpacking the expectations you had about attending this institution. It’s a place that has a mythical reputation, and I wonder what the reality is.

ADT The biggest shock was coming to the school and seeing the lack of people that were here to make work for themselves. It seemed that the spirit was more about getting a degree and handing in assignments. “This is my homework and I want to be able to fit the expectations of the teacher.” It wasn’t a matter of starting a lifelong project.

Maria Kuraeva: I had an expectation that there would be more people at the school involved in the field and interested in the discourse as a whole. We are able to find our friends here and a few others throughout the school and obviously some of the faculty, but it was a strange thing coming into a school that’s super specialized and yet not having the majority of its population involved in the conversation.

Sam Harding: I can immediately map this onto my own experience of the emptying-out of the space between academia and the university degree as a product. How does this resound in the context of SCI-Arc as an institution now offering an accredited diploma?

WM I grew up around a lot of people who went to SCI-Arc at different points of its history and so I got a sense that it was a school in flux, but the thing that was constant in its reputation was that people were serious about experimentation.

RD Yes, the reputation of SCI-Arc is that it is big on failure, letting ideas completely undo themselves even. When we first came here, we realized that spirit wasn’t as present as we thought. Currently, it’s institutionalized.

MN How much do you think experimentation and failure can be accommodated within this institutionalized condition, or is it just about producing legible projects that work?

MK Funnily enough there’s not a lot of production of legible products that actually work. Projects here are very formally based, and the operation of the architecture comes second. A lot of the experimentation isn’t based on interactions with the city and culture or within the site of the project.

ADT There’s also a weird insistence on being anti-architecture in the production, but also with a strong emphasis on getting an architectural degree. You have a certain studio with a formal imposition that’s basically some sculptural game, and there’s no space left to do architecture.

MN I go to school in Spain, and there seems to be a formula for what a semester will look like. One starts with studying the context, then formalizing it or coming up with perhaps arbitrary moves to serve as a metaphor for the intention of architecture.

RD We go through that same process a lot, but there is a diversity in the kinds of move or metaphors employed.

ADT I don’t think that you can escape architecture being a formal metaphor. The question is: why are you still working on that? Why hasn’t anything changed in your practice? Some teachers probably have been cooking up the same thing for more than ten years.

MN If there is a positive for formal experimentation is that it’s essentially infinite, and to have someone that’s stuck in the same place for ten years is quite concerning.

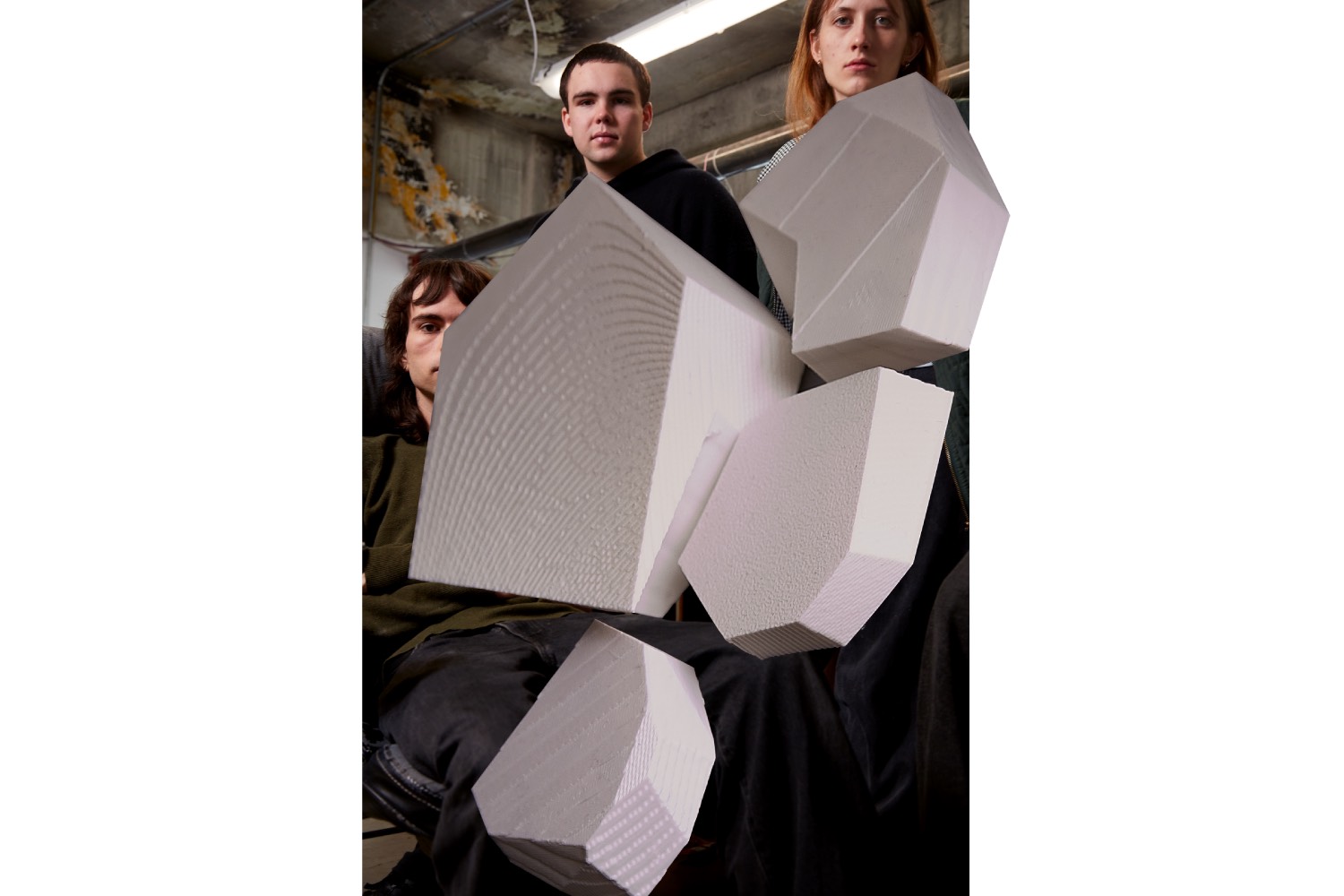

RD There’s also a reliance on drama in SCI-Arc — the kind of theatrics of the presentation and how big your model is. This leads to this kind of blunt, insensitive design where it’s meant to garner shock and awe.

SH So a situation where the drama of the project masquerades as experimentation. Manga was describing the evolution of SCI-Arc to me as one essentially defined by its relationship to precarity. During the ’70s the question was: “Would this still exist in a year’s time?” Obviously precarity has its kind of negative echo in the architectural discourse about labor and the viability of studio practices. If we’re grappling with that word, what might it mean to embrace precarity as a studio or as an institution?

ADT I think that if you embrace the precarity, it means you’re immersed in the real, and you’re not trying to be insular, and you understand the risk you’re taking by being part of this kind of work.

MN I’m interested in how this process replicates itself in the professional world, how education and practice are standardized thanks to external economic pressure, and of course the ideological paradigm in which they reside. If we connect that to the ways that some of the most prominent architecture firms have developed over the years, one wonders if economic or ideological concerns took a backseat and professional practice was brought to the fore. If it wasn’t about saving the studio and adding a bunch of partners into the mix, how would that create an architecture that was about the personal project rather than this professionalization that we’re seeing?

ADT I think in the US, we’re facing the extreme situation that there isn’t any true value ascribed to design. You just have to be efficient. And I think a lot of offices were put in this situation without it being a conscious decision. It was just that: “If I’m going to continue being an architect, I need to make costs.”

RD Yes, you have to do projects that aren’t interesting, obviously just to keep an office running. A practice that’s doing consistently interesting work is, with few exceptions, at least in the US, a very small practice that depends economically on academia to sustain itself, which is the case of a lot of our instructors. Some of them have interesting practices, but they depend on their teaching to pay rent. That’s just an economic reality. You can’t always do what you want.

SH A bit of a tangent here: in the 2023 series The Curse, starring Nathan Fielder and Emma Stone as the hosts of a new house-flipping reality-TV show, the central motif is the stylized eco-home they construct as socially conscious developments across a New Mexico community. These houses are rectangular boxes encased in a metallic, mirrored cladding. Basically, they’re amalgamated checklists of philanthropic branding and carbon-neutrality, combined with the Instagrammable patina of an art installation. Of course, at the end of the day it’s just gentrification à la Doug Aitken. These mirrored oblongs seem to be parodying the idea of architecture as a stable image, one in which all of its claims to social, environmental, and aesthetic intent are congealed into a single building — a visual metaphor for nothingness; one that conceals the distortion its presence entails by literally reflecting the world around it; one in which architecture is not present except as a transparent sheen for capital. How might you navigate this condition?

ADT It feels like the antidote relies heavily on very focused introspection from students. And it is easy to consciously ignore that because it complicates what you’re being asked to do in architecture school. Sometimes it’s hard to engage the issues head on. But I think it’s required for us to have difficult conversations and to embrace the cognitive dissonance that comes from wanting our work to engage environmentally, but at the same time thinking about the manufactured innocence that can come with that.

RD In terms of environmentalism, architecture should get ahead of legislation. Just following these protocols and standards of what is an efficient system is obviously not enough.

MN It feels as though practice globally has stabilized and that there aren’t many notable differences aside from client base and scale of project and the profile of an architecture firm that distinguishes many practices. There’s almost a poverty of theory or proposition being presented as part of practice. Are there any firms or figures that you’ve found that break this malaise?

ADT I have to say no.

MN Is it that the ideal architecture firm doesn’t exist? Or is it that you just don’t think anyone is seriously engaging with it?

RD I think it’s still unclear what an architect’s supposed to do. I don’t know how to articulate it better than that.

ADT At the end of the day, people are hiring you for your opinion, and that doesn’t necessarily need to be applied to buildings anymore. Of course, it can be because that’s what we’ve historically done, but now we need to be stakeholders in the designs of all sorts of different structures beyond buildings. But we don’t really know what those are.

MN There’s a long history of the figuration of the architect, but recently it’s mainly been about establishing a legible and mediagenic persona, and you see that in the institutions that we attend. Do you think there is any way around that?

RD There’s the subscription to the standard media that makes you see it and say, “That’s architecture, that’s an architect.” You can tell by the drawings and the photos. I don’t know about people who break that mold because it’s hard to tell where the architecture line stops when you start breaking that mold.

MN Sam and I have discussed architects that come from other worlds, the way it feels like Luigi Alberto Cippini has emerged from a synthesis of fashion and art and has more recently become a practitioner. Virgil Abloh as well in some sense, only getting involved in architectural interventions towards the end of his career. It feels as though the kind of experimentation and the space for the expansion of who the architect is perhaps through other worlds and not through the architecture establishment itself.

WM To go along with that, I think the antidote — which I believe we agree Luigi has and potentially Virgil and others have — is a vagueness in their work and a connection to other fields. And in the way that they operate and communicate with other people through social media or whatever media resource that they’re utilizing. I think that Luigi particularly does this well. At first glance, you don’t really think he’s an architect or know what he’s doing. You’re interested in it and you’re not exactly sure what’s going on or why, but there’s a mysteriousness to it that makes it very compelling.

MN The fact that it’s not digestible at first glance and it’s not claiming to be stable, because it truly is a messy profession where you’re dealing with multiple interests and the attempt or the audacity to keep it free or to expose all the elements, to keep it auxiliary, is brave, for lack of a better word.

Luigi also keeps telling me that he’s very interested in projects that are bad, especially student projects. And I wonder if he’s talking about the freedom to fail, which I think is something that we all value, especially within school, because the lie of a project that works in school is just so seductive.

ADT I think the blatantly bad project is interesting because it has some sort of honesty.

RD Well, it more clearly shows, in its crudeness and fast pace, the role of intuition in architecture practice, which I think we dismiss a lot, at least at school. In practice there’s a need to have a reason to do everything and to do it right the first time, but it can be easy to forget about our first intuitions, which sometimes are right and sometimes are horribly wrong. But we learn a lot from working from those intuitions and letting them fail.

MN Well thank you all for joining us for this conversation and I wish you well.

SH Thank you for indulging our innocence.