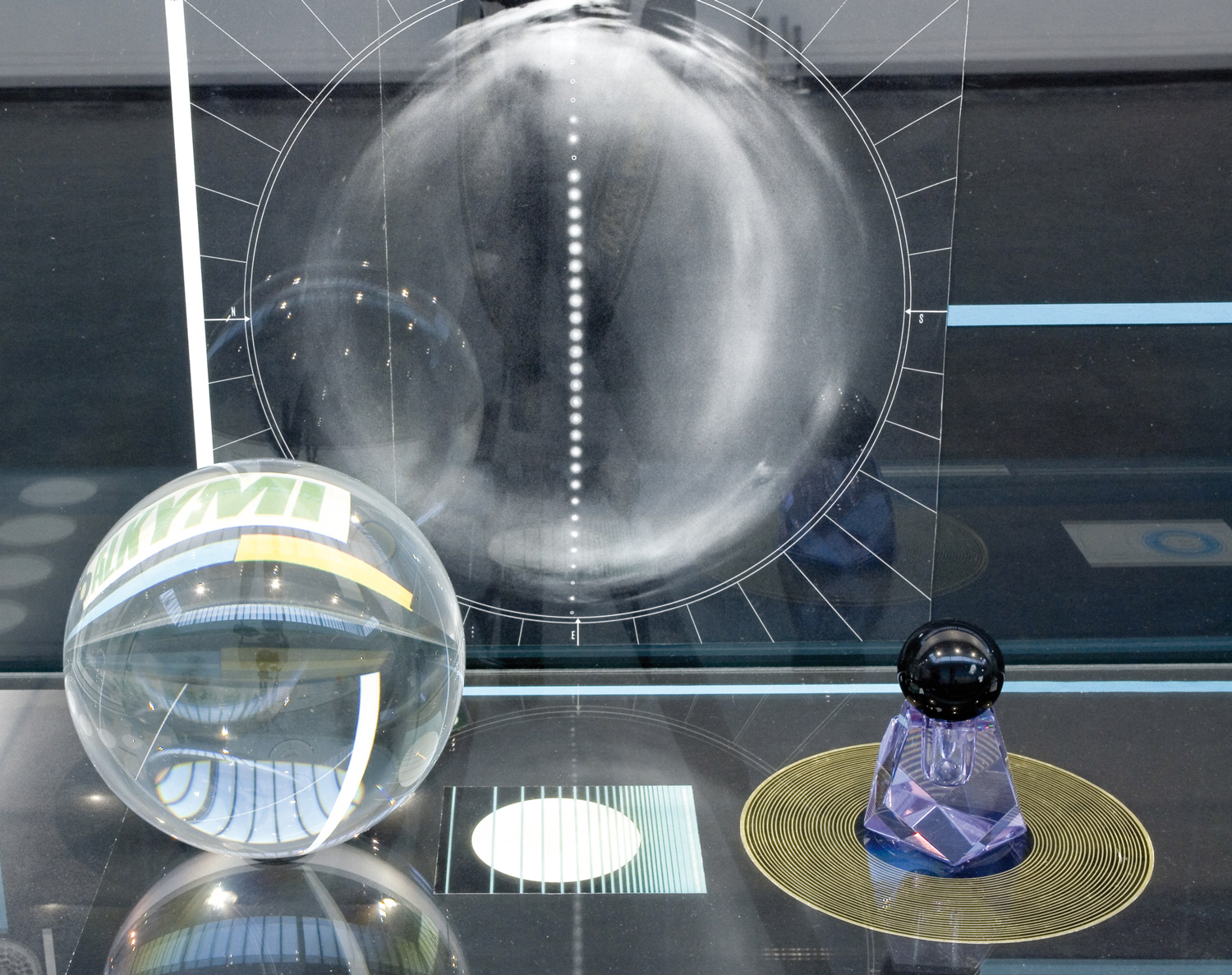

“Visibility is a trap,” says Foucault in Discipline and Punish, describing the Panopticon prison structure. A disciplinary model, in other words, in which the simple fact of being exposed or made visible is automatically transformed into a method of subjection and repression. And an actual human trap that works optically is also what Santiago Sierra has recently created for the Centro Cultural Matucana 100 in Santiago, Chile. A large device for seeing. Indeed a trap, as the title of the work La Trampa says. But to capture who? Using what tactics? And why?

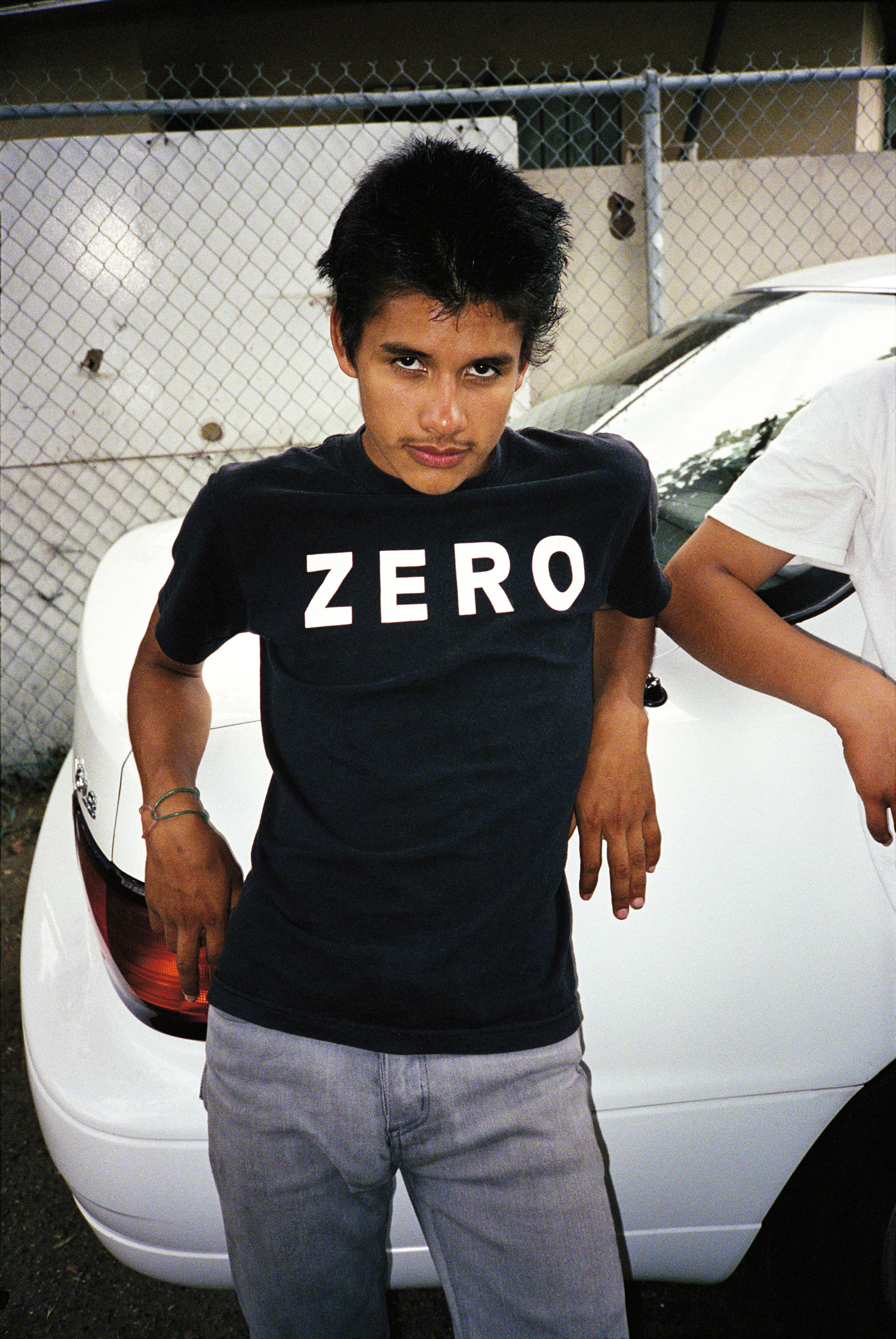

On the evening of last December 27, a handful of members of the Chilean “power base” were invited to the Centro Cultural Matucana 100 to take part in an event with a rather unusual procedure. According to a hierarchical ranking system from political to cultural and lastly to media power, their respective representatives were invited — one at a time — to pass through a doorway from which they would never return. A few names? The President of the Chamber of Deputies, Patricio Walker; the Secretary General of the Presidency, José Antonio Viera-Gallo; the Minister of Defense José Goñi; the rector of the University Diego Portales Carlos Peña; the famous art critic Nelly Richard; the director of the Contemporary Art Museum Francisco Brugnoli, as well as other personalities, including the most important journalists from the major newspapers. Once beyond the doorway, each of them, completely alone, followed a seventy-meter-long narrow wooden corridor that brought them to the center of a theater. Suddenly each one found him/herself surrounded by 372 eyes staring impassively and in silence under spotlight beams. Arranged in tiered rows, 186 Peruvian workers occupied the entirety of the stalls. What were the spectators to do in front of such an audience? Escape? Give a speech? Just stand and look? As if they were on a fenced-off dais, the representatives could only look out without moving forward, and then take their leave and withdraw into a new corridor from which they were able to exit, finding the previous one blocked. Having assumed the role of spectators in the Santiago Sierra show to which they had been invited, to their surprise and unease, the 13 representatives of Chilean power found themselves unwittingly transformed into actors before a crowd of observers composed in the main of illegal immigrants, underpaid and exploited in Chile. But also the actors of the piece (the Peruvians hired and paid by Sierra) found themselves playing the role of spectators — in this case consciously. If the 360 Mexican temporary workers at the Rufino Tamayo Museum, the 430 Peruvian women at Lima’s Pancho Fierro Gallery, or the 396 Romanian women of the MNAC of Bucharest had been exposed to the audience as they were, the Peruvian workers in the Chile piece would assume the role of spectators. So who is watching and who is being watched in this performance? Who has been caught in the trap in this piece for 13 spectators and 186 actors? The Chilean spectators who found themselves observed and judged? The Peruvians who were willing to become spectators on the order of the director for the meager payment of 7000 pesos? The artist himself who plays the power role, accepting a fake, precautionary, personal alienation as a defense against an imposed social reification?

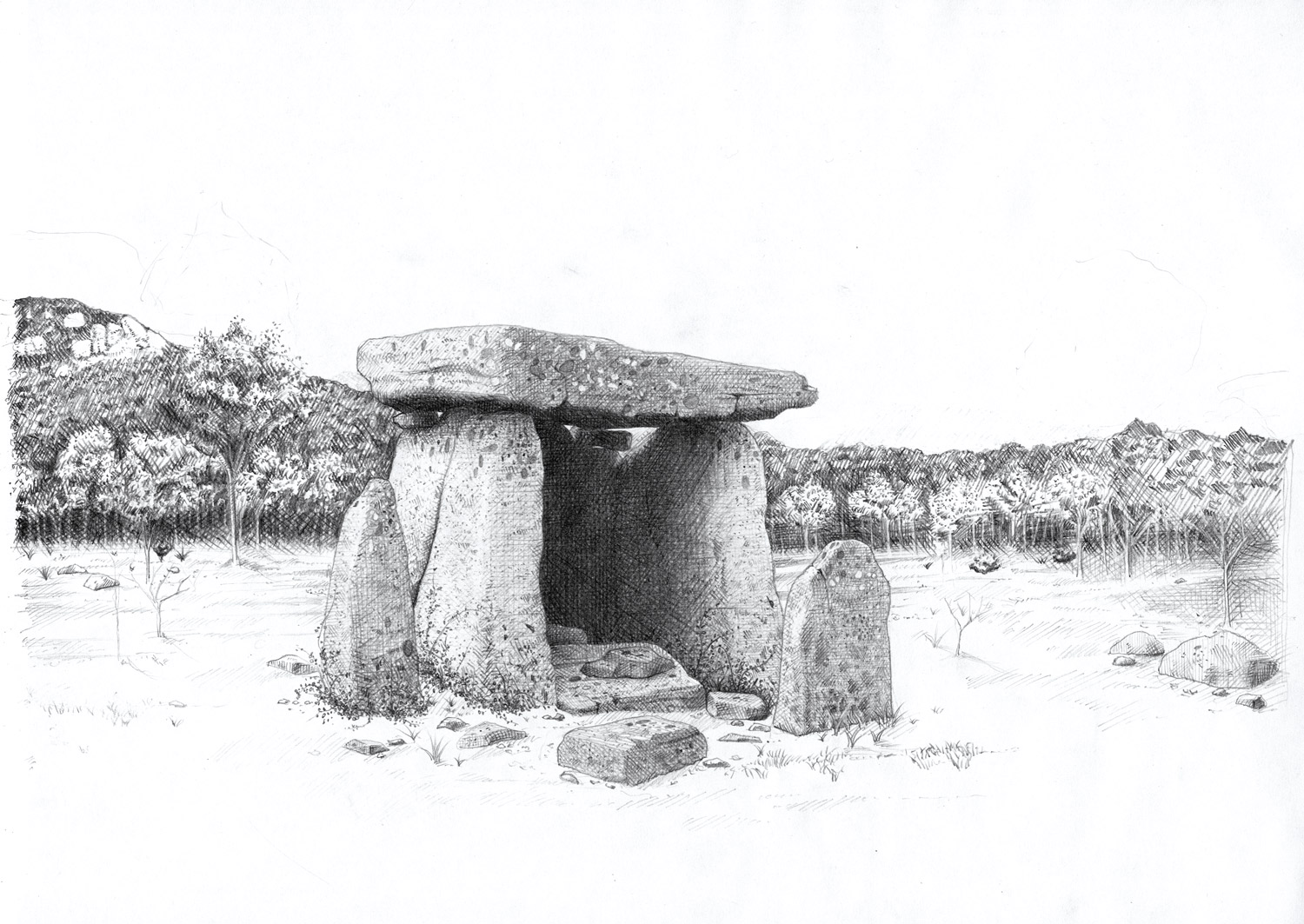

Here the trap does nothing less than make the different scenarios of power visible. Sierra’s La Trampa is a representation of a representation of contemporary power. A great Las Meninas of our time.