Over the course of more than two decades Rudolf Stingel has brought to the fore an approach to painting that is as much about seeing as it is about making. Moving freely between abstraction and representation, in both intimate and monumental scales, Stingel has seduced viewers with his ornate surfaces and simultaneously undermined expectations of what painting can and should be. For his exhibition at Gagosian in New York, Stingel presented three series of new paintings (all Untitled from 2010) that alternate between hyperrealistic self-portraits, decorative silver carpet paintings and process-oriented gold canvases.

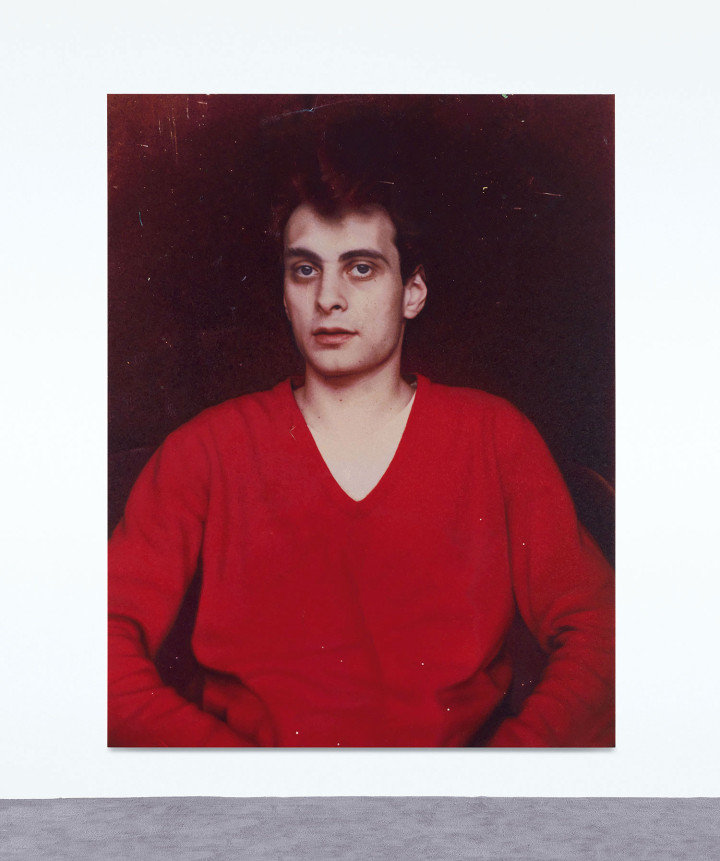

Stingel’s approach to self-portraiture not only examines the binary of biography and painting, but also takes on the conventions of self-examination itself. Many of his recent self-portrait paintings showed the artist looking rather pensive and uncertain in his middle age, either lounging Christ-like in bed or casually smoking while looking away. The four self-portraits presented here are based on a photograph of the artist as a young man, vibrant and confronting the viewer’s gaze head-on. Here Stingel draws attention to the surface, depicting the rips, spots and water damage of aged photo paper. A suite of three seemingly identical and monumental self-portraits in grisaille hang in a room all their own, inspiring “awe” and subverting the viewer’s experience. The works provoke sheer wonderment at the artist’s ability to translate a casual snapshot into an epic, psychologically probing portrait, and yet also draw attention to their banality and mechanized production (the photographic image is enlarged into numerous grids, which are then painted in orderly sections). In this sense, Stingel challenges the notion of self-portraiture as a mark of authentic time and place, instead highlighting the genre’s potential for abstraction and exploration of identity’s fluidity.

The main stunner in this series is also the show’s final work, Stingel’s first self-portrait in color, based on the same photograph. Here the deep red of his V-neck sweater and the burgundy of the backdrop are significantly vintage in hue, evoking a well-aged snapshot. Stingel’s use of color highlights an incongruity between past and present, and offers a meditation on layered memory, or a reality in flux.

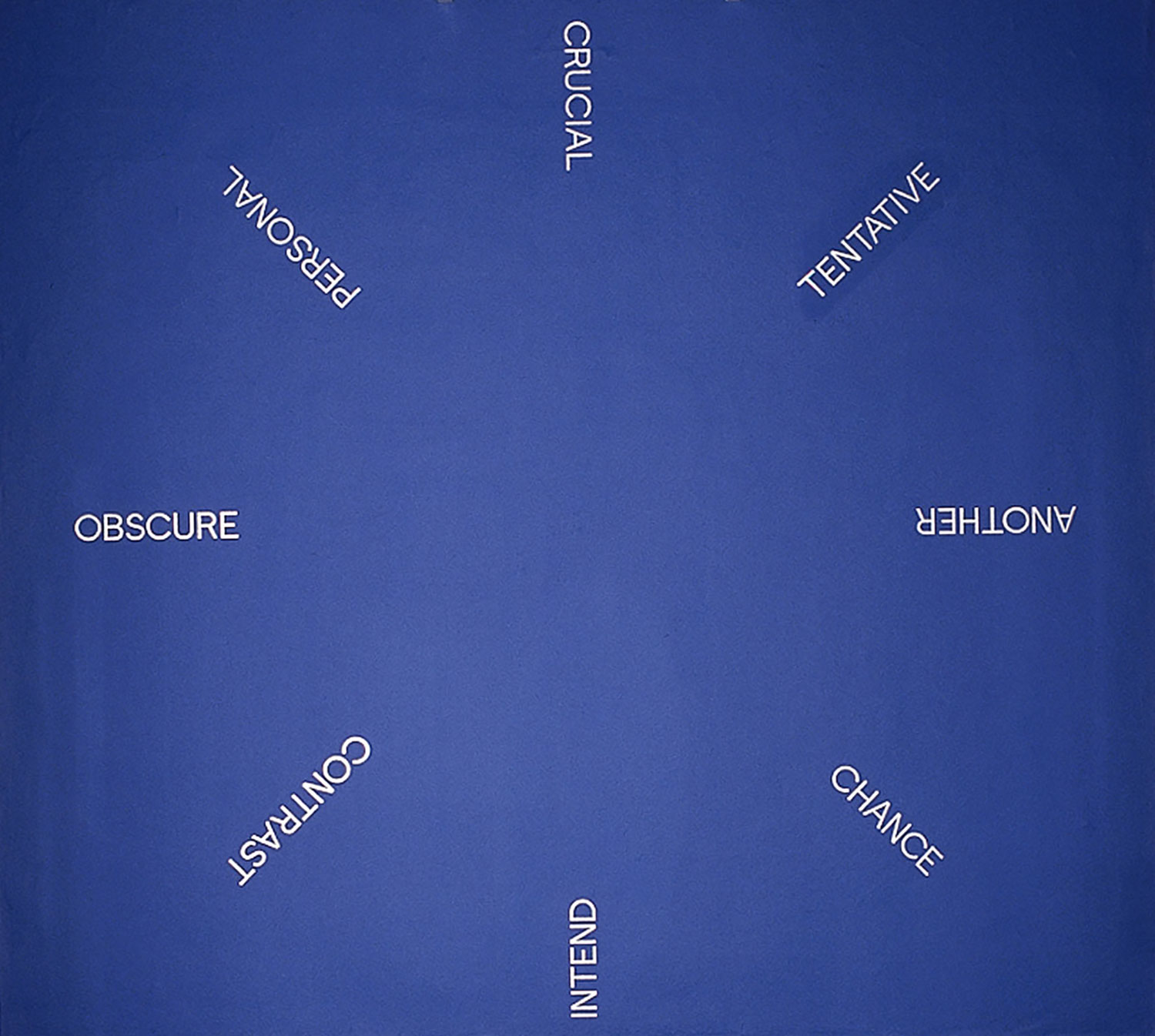

The next two series continue Stingel’s engagement with precious metals and the artifice of glamour. He once said, “Silver makes everything look contemporary.” The artist has never shied away from referencing the “decorative” arts. Here he references a brocade woven carpet via his signature layered and stenciled technique, giving the impression of embroidery and depth. His Baroque ornamentation is defiantly filtered through a Warholian DIY approach that evokes a kind of readymade opulence. Installed in a narrow, nave-like passageway, the sensation of his ten canvases is of a serene cathedral or a hall of mirrors. Stingel has played with spiritual subject matter in the past, though there is nothing explicitly spiritual about the decorative elements here — unless painting itself happens to be your religion.

Whereas the silver paintings only subtly reference the floor in their subject matter, the five gold monochromes that command the largest gallery were literally created on it. The works record the act of their own making, via the residue, footprint stains, scratches and oxidation marks that dominate the gold-plated surface, like a tougher Warhol Piss Painting. The juxtaposition of rich gold leaf with cheap refuse and nontraditional materials is startling, even aggressive at times, considering the space of luxury in which the paintings hang, and the banality of elegance they communicate.