Lucy Rees: Your recent exhibition “Fiesta Carnival” at Primo Marella Gallery in Milan explores concepts of transgression and border dissolution.

Ronald Ventura: It was inspired by an amusement park in Cubao, Quezon City, at the heart of Metro Manila, that was popular during the ’70s and ’80s. As kids, our parents took us there during weekends and holidays. Fiesta Carnival was the closest thing we have to the circus. For me, I use this as a link between European and Filipino cultures. It also reminded me of the American carnivals that were prevalent when my country was under colonial rule. We have been colonized by so many different cultures, such as the Spanish, Americans and the Japanese. I chose the carnival theme, as it is a bridge between different cultures — a way of representing the different cultures passing through, and the relations between different sides. Tribute, for example, is a depiction of the motherland as a female figure, used as a stomping ground or playground site by the circus characters (magicians, jugglers, caricatures of American and European origin). She is a sort of “tribute,” something of sacrificial value — a part of the dynamics between colonizer and colony.

LR: Your practice is constantly evolving. From your earlier works defined by a hybrid figurative surrealism, to the fiberglass sculptures of “A Thousand Islands” at Tyler Rollins in October last year, through to these fantastical, imaginative works on display at Primo Marella. Where do you find your constant inspiration and creativity?

RV: Inspiration comes from different sources: the Internet, television and books. I also travel a lot, thus I soak up a lot of culture from other countries. My work is like a constant compression or compendium of cultures. Subconsciously, my mind absorbs various information and ideas — even if it’s beyond my control. I want to create a dialogue between the past and the present.

LR: What has the journey up to now been like? Can you mention a few highlights?

RV: There have been some memorable moments for me. Getting recognition from local artistic institutions and winning grants. I won an award given by a distinguished art institution, which allowed me to travel to Sydney in 2005 to mount an exhibition. I saw many artworks in museums — from the Renaissance to contemporary art — that I only saw before in art books. These trips have been crucial to my development as an artist. It made me constantly analyze what is going on in the art scenes of different countries.

LR: Let’s speak about influences. Have any Filipino painters from the older generation inspired you?

RV: Definitely! There are a lot of great artists. But for me art is about developing a visual language, so I feel like there are a lot of artists that I admire, but they are more of an inspiration than an “influence.” My work has been inspired by so many art movements, groups and periods — from conceptual to figurative to pop art.

LR: Can you feel the increasing interest in Filipino contemporary art? Your work Greyground (2011) reached the highest price ever at auction for a work by a Southeast Asian artist. Has it affected the way you work now? Has anything changed?

RV: Well, I had no control over that. The auction houses are the ones who made that possible. Of course it has improved things, because this recognition has allowed Filipino art to be aligned with the rest of the Southeast Asian and the international art world, creating a more even playing field. But this hasn’t affected my process or methods in creating art at all.

LR: Do you think your success has opened doors for other Filipino artists?

RV: Personally, I have no interest in that. But yes, the movement has opened the possibility for us to do more and to give a chance for others to grow.

LR: Tell me about your process. Your paintings are intricately and complexly layered, often revealing a subtle irony and humor. I hear you sometimes work obsessively for ten hours at time; is art making a sort of escape for you?

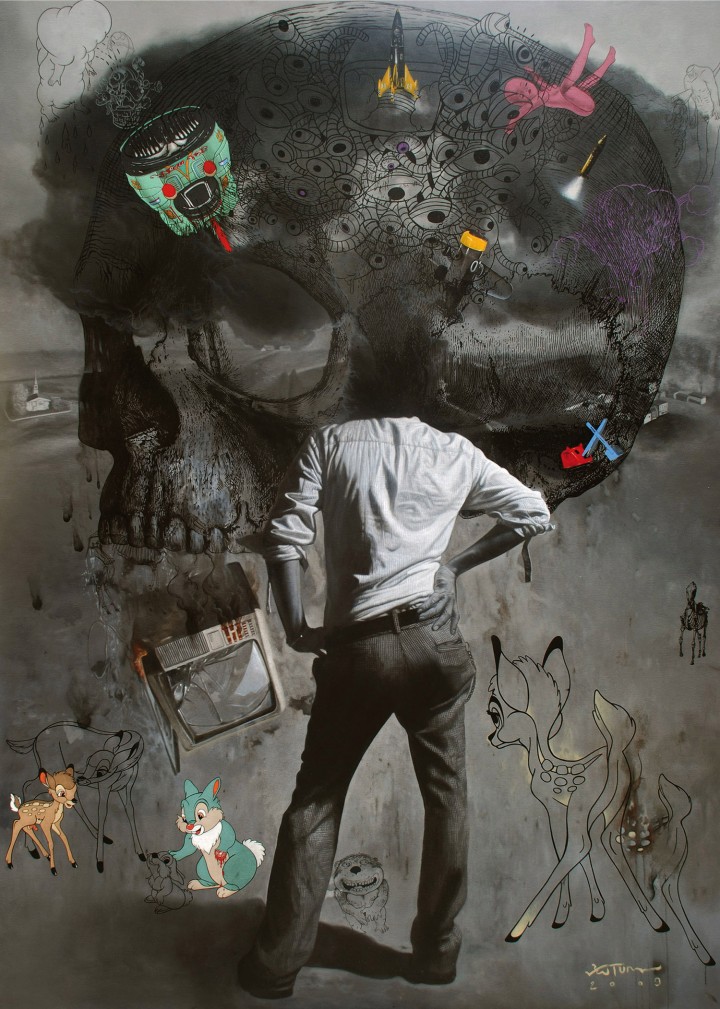

RV: It’s not an escape; it’s more like a release for me. We are so bombarded with bad things happening. There is so much influx of images that they seem to suffocate me, and sometimes it’s hard to digest everything. In terms of process, I could liken it to a work done in Photoshop: there so many different layers (culled from history, pop art, cartoons, anime, realism, photography — you name it) that are compressed into one flattened plane. But in my case, I use traditional methods of drawing and painting to create a big visual sandwich.

LR: You live and work in Manila; what is your experience there as a practicing artist? Have you ever felt the desire to live and work abroad?

RV: No, not at this point in my life. I have a family in my country. Art making for me is a big part of my life — but it’s not everything. At the end of the day, an artist still goes home to his family.

LR: I understand that there is no contemporary art museum in the Philippines? What do you hope for the future of culture and the arts in your country? Is there a need for stronger infrastructure and support?

RV: There are a lot of private individuals and institutions supporting art in the Philippines. I am glad there are a lot of people nurturing and expanding their contemporary art appreciation, but there is much to be desired. That being said, there is a lot of contemporary practice and dynamism in the Philippines, especially in Manila.

LR: Your success is often attributed to your ability to make works that represent a global disposition while being distinctly rooted in the local. Could you talk about that? Are you trying to make a pointed social commentary?

RV: It’s just how my life is: Sometimes I’m a father, sometimes a gardener; sometimes I’m just the guy who washes his car. Each person has his or her own job; whether you are a worker, farmer or a fireman. As artists, we have different methodologies, different ways of looking at art. I don’t think there is any hierarchy of artistic genres. We are all social beings; one can’t avoid being affected by society, but it’s just a part of my artistic practice. It’s not the totality of my art. But it doesn’t mean what I’m saying or what I’m doing is more important than what is created by others.

LR: What are you going to be working on next?

RV: I have an exhibition in November that is inspired by the northern part of the Philippines. The show for the Vargas Museum is my own take on promoting indigenous culture. That’s why I chose to create sculptures with the Bul-ol or the Ifugao Rice God as subject. Another artist in the past made a social commentary about the Bul-ol as something alienated from its ritualistic power and relegated to a decorative, domesticated prop. I, on the other hand, am simply exploring the Bul-ol as pure object/form. I have created different sculptures of it (in pairs or as standalones) with different variations — anatomical figures, tattooed, cubist, angel-versus-devil, etc. You could call it “jazz up your Bul-ol,” although my take is more respectful, purely driven by sculptural shapes and contours, and as a curious outsider peering into a more mysterious world. This is also my way of taking something of ceremonious value in the Filipino culture and rendering it as pop, as infused with the images of today (from Final Fantasy to Transformers), contemporarily mythic.