I met the artist Rodrigo Hernández (b. 1983, Mexico) one year ago, when he was on a residency in New York. He invited me to his studio and we began an ongoing dialogue. In that first meeting in his apartment and work space in Brooklyn, we sat at a desk he had set up in front of the windows of his bedroom, looking out at a nondescript, semi-industrial landscape. He would sit there and observe the light as it reflected off of three neighboring buildings, two painted different shades of yellow and one brick, set against a plain blue sky. Over the course of his six months stationed in the room, he produced twelve simple compositions of this same scene in oil on board (Untitled [NY Paintings] [2016]). Similar in size and subject to Etel Adnan’s meditations on Mount Tamalpais, his compositions were more hard edged, graphic and focused on recording the subtle changes in light at different points of the day and under different meteorological circumstances. At the time, the works seemed to be an auxiliary practice, more a form of meditation and daily ritual than a series connected to his main preoccupations.

In broad terms, Hernández makes sculptural installations, small paintings and drawings related to autofictive narratives. His practice concerns intellectually abstract subject matter indebted to existentialism, Surrealism, Mexican art history, pre-Columbian culture and an endless list of literary references including Patrick Modiano, Robert Walser, Juan Rulfo and Bern Porter — to name the most recent. Much of his work — particularly the characters found in his drawings — is inspired by a sub-professional aesthetic: moments in visual culture that betray a lack of total formalization — evidence of personal flourishes by unknown artists, visible in objects meant for public use or display. Likewise, he is attracted to drawings by non-artists, such as those by Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, a Soviet scientist who produced annotated illustrations related to early Russian space exploration. Or work by children, an area of study that recently inspired an installation, The Shakiest of Things (2017), which he produced and finished with the aid of local youth in an exhibition at Kim?, in Riga.

Hernández was born and raised in Mexico City, which he still considers to be home. He studied Mexican history and philosophy at university before switching to art, and finished his degree in Karlsruhe, Germany. Following encouragement from his teacher, the artist Silvia Bächli, he stayed in Karlsruhe and pursued a master’s degree there. Bächli became a source of inspiration, a mentor whom he now credits with changing his way of thinking about art and what it might be. In 2013, Hernández continued his studies at the Jan van Eyck Academie in Maastricht, Netherlands. In 2015 he spent another year in Europe, at the Laurenz-Haus in Basel. Consequently, he developed a network in Europe, and when we met in New York he was planning a solo exhibition at the Heidelberger Kunstverein, which opened this past November. (By coincidence, Bächli received an invitation to exhibit at the museum and they timed their exhibitions to coincide.)

The exhibition in Heidelberger was titled “I Am Nothing.” It began as just a concept, an allusion to the first line of Modiano’s novel Missing Person (1978), in which the main character obsesses over the disappearance of his own footsteps as he moves through the world. Hernandez was thinking about what it means to strip “man” of everything, including the ability to find meaning in life. Since 2013, he has produced installations centered around a simple, human-size anthropomorphic figure titled simply Figure 1 (2013). It is made of papier-mâché on a stainless-steel frame and resembles a scaled-up version of a white marble statuette from the Cycladic period in Greece. This “man” traveled to Heidelberg and occupied a central position in the exhibition. The figure was to be surrounded by various sculptures that looked like everyday objects, as well as paintings and drawings. For Hernández, the objects that “he,” the figure, was to “receive” were supposed to be the basic, quotidian things that we relate to as we move through life. At the same time, the objects were meant to fail to perform that role of relatability, as they were designed to remain unfamiliar, unrecognizable and distant. For example, an apple made of painted papier-mâché is at once an apple and a work of art. The objects are enigmatic. They are meant to be puzzling to the “man,” but they are also “real” sculptures. The project is a kind of meta-reflection on the act of making and its relation to how we make meaning in the world.

To put that rather dense idea into some kind of perspective, Hernández is drawn to Surrealism — particularly de Chirico’s lengthy experiment in hermeticism, in which he attempted to conceal literal meaning in his artwork. To inhabit one of de Chirico’s psychological landscapes is like being in outer space; it is an opportunity to rethink the way we do the most basic things on earth: how we cry, how we clean a glass, how we open a door… There is the potential to think and see through the lens of a child, testing and questioning the way we do the simplest activities in our everyday lives. Hernández’s Figure 1 is meant to be like a conduit for reflecting upon our status in the world. “He,” the figure, encounters objects for the first time without any context and must make sense of them anew. How do we know that an apple is something we consume? And why do we pick it up, bite into it and chew?

This idea to question all a priori assumptions about basic aspects of life occurred to Hernández long before his art education. His parents sent him to a Japanese immersion school in Mexico City until the age of seventeen. The school was established in the late 1970s for the families of Japanese business people in Mexico. Hernández was one of the only students without any Japanese background. He was taught by Japanese teachers who did not speak Spanish. So at an early age, he learned a foreign language and was introduced to an alien culture. Most importantly, he did not learn through translation or by comparison to Mexican culture, but through images, gestures and repetitive actions. This intuitive, immersive education involved a mode of translation from ideograms and drawings to language and vice versa. For instance, in Japanese, the character for the word “mountain” is derived from an image of a mountain. At the same time, “mountain,” when placed next to another character, may suddenly create a third, totally new word divorced from any direct relationship between the two individual characters. The words were always explained through small, simple diagrams and never in relation to Spanish. Or the same phrases were used daily until their meaning became clear. Eventually pronunciation was introduced, but his primary education was based on reading and extracting meaning from images.

Hernández’s experience at this Japanese school and his early exposure to seeing the world through the lens of a radically different culture informs his general approach to artmaking. He would watch the students in “Section A” — the most immersive section for students planning to return to Japan — eat their lunches, and he realized there were totally different ways of doing the most common ritualistic activities. Instead of beginning from the premise that we all know what the world is, that it is one thing, and that an artist can find some sort of Archimedean point above it, from which she looks down and produces art and commentary, his work remains stuck in the swamp of the world; it tries to understand, first and foremost, what are the consensuses and disagreements we have about the world — why, for instance, is a piece of writing paper white and square; or why is an exhibition, with its standard formulas and timespans, like a dark suit that all have agreed to wear to work everyday.

Some of the “NY Paintings” were included in the exhibition in Heidelberg, and over time, through our conversations, I began to understand the works’ connection to the rest of Hernández’s projects. Although he is interested in the meditative aspects of drawing and painting, the façades take on a different meaning when placed in the context of Figure 1, of paintings inspired by Tsiolkovsky’s drawings, or of the artist’s continual fascination with Magritte’s approach to language. In Magritte’s Les mots et les images (1929), there is a small drawing of a brick wall with a caption that reads (in translation): “an object that makes you think there are other objects behind it.” The walls in Hernández’s painting in some ways act as barriers to meaning, barring entry into the picture in order to make sense of it. They keep you on the surface of the work, inside the exhibition with Figure 1, trying to sort out the world anew alongside him.

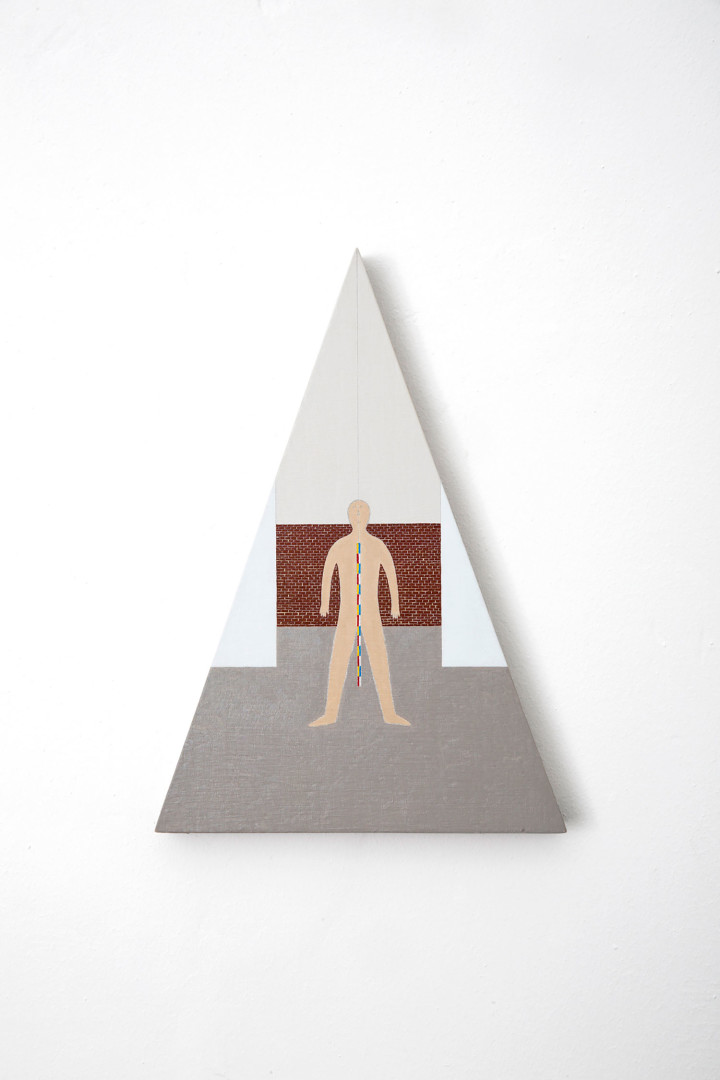

That is a rather simplistic and literal interpretation. It is tempting to reach for meaning when it dangles so low to the ground like this, whereas most of Hernández’s paintings and drawings deliberately resist such smooth explication. For instance, silhouettes resembling Figure 1 and brick façades appear in other paintings, such as a small, triangular oil on wood titled A Reminder (Who needs you every minute) (2016). In it, a simplified human figure stands in front of a brick wall framed by two white walls. A stripe of primary-color-patterned rectangles runs partway through the middle of the figure. The work, especially the triangular form of the picture plane and the enigmatic strip of color running through the center, resembles the mystical abstraction of Hilma af Klint. Most of Hernández’s drawings and paintings are difficult to write about, because they begin in language and depart into a highly coded visual logic.

The paintings in the series Selva (2016–ongoing), for instance, form scenes in an autofictional narrative about a woman named Selva, who records and transmits to the artist her boyfriend’s dreams about the murals of Mexican artist and historian Miguel Covarrubias (1904–1957). These works draw particular inspiration from Bächli, who uses long and poetic titles or explanations to illuminate highly economical compositions and line drawings. For instance, in the small painting We are walking together in Paris. I show you my open hand and the things I had inside my pocket (2016), a pale, open palm, depicted against a solid gray background, holds four tiny, anthropological or nondescript objects. Another in the same series is titled A bird lands on our table and plays with the patterns on the wood, like jumping from one place to the other of a map (2016). The latter describes a scene of two figures at table in a placeless dreamscape. Together, the works are clues to a story never meant to fully emerge, but instead to take us somewhere beyond language. Hernández’s story makes us aware of our need to form meaning, and his works encourage us to reach beyond the ways we have been taught to make sense of the world. Ultimately, the artist invites us to experience the world as if we had just arrived.