Maurizio Cattelan: I am going to ask questions about family because I imagine your creative process to be familial and unfold almost like a family tree.

Kate Mulleavy: Exactly. When I was little I imagined that my family life was a film and that ultimately we had no control over anything. I wondered what the people were like who were watching it.

MC: So starting with the basics, you’re sisters?

Laura Mulleavy: Yes.

MC: The places where you spent time as children have impacted your design language. Can you talk a little bit about how different environments shaped your point of view?

LM: Kate and I are very inspired by where we grew up. We grew up by the beach near Santa Cruz (the town The Lost Boys takes place in) among tide pools, redwood forests, mustard fields, California poppies and apple orchards. We were surrounded by the mythology of Steinbeck and Kerouac, and the entire landscape had a sort of hazy atmosphere. Hare Krishnas, psychedelic skaters, hippies, punks, surfers — all of these memories shaped the way we think creatively. Northern California, by nature, is a landscape that is wild, and the culture that has come out of that history reflects this.

KM: Our house rested right on the San Andreas Fault. I can remember a huge earthquake happening one summer. I was standing in our kitchen and within a few seconds every porcelain plate, bowl and glass cup had literally flown off the shelves and shattered on the floor around me. I remember being mesmerized by the shards. A broken plate will always be more interesting to Laura and I than a perfect, untouched object. The value is in the stain, the shadow, smudge, tear. We are attracted to imperfection and to the beauty of chaos.

MC: Is there one collection that you’ve designed that most represents your personal history?

LM: Our Spring 2011 collection was about Northern California. The collection played with the idea of redwood forests, fake wood paneling (both common where we grew up) and the idea of a California cowboy. Our cowboys took the shape of samurais, gladiators (which was a reference to the state seal) and Chinese warriors. The collection was inspired by the layered history and culture of the region, as well as the suburban sprawl.

KM: Our Spring 2010 collection was also inspired by the California Condor, which is native to where we are from. Spring 2009 was inspired by our all-time favorite film, Star Wars, which we watched over and over as kids. We were inspired by the story of outer space told through human perspective and understanding. In Star Wars, the pristine white machine Stormtroopers get dirty, which allows the viewer to relate to outer space in a physical, human way.

LM: Even our Fall 2009 collection, which was about Frankenstein and Gordon Matta-Clark, related back to the landscape that we come from. The inspiration for our Fall 2009 collection came in an unexpected moment while we were driving along the 110 freeway leading from downtown Los Angeles to Pasadena. A large piece of insulation had fallen off a truck and drifted near the side of the freeway that reveals a row of old Victorian homes. The piece of insulation was dusty pink and coated in thin silver foil. We decided that the world that we wanted to create was one of a deconstructed site; one that was both archaic and futuristic. Layers upon layers of texture; piles of rock, granite, marble, grout, dry wall, insulation, copper piping, gravel and wood. Works of art by Gordon Matta-Clark and, of course, Boris Karloff in Frankenstein captured that feeling. How could the ultimate science fiction figure not relate in its entirety to the iconic configuration — or disfiguration for that matter — of the home? With this collection, we wanted to explore the process of building, ruin and preservation. Upon seeing our collection completed we began to see its connection to the arid desert landscapes that we had grown up with. Joshua Tree National Park, whose dominant geological feature is of bare rock, broken into loose boulders and stacked into piles upon piles, is also speckled with the most charismatic and delicate trees known in existence. The combination of fragile sand tones and strange green hues acts to magnify the contrast between the park’s severe desert landscape with its bizarre flora and fauna. How does a prehistoric-like world seem to remain so preserved and perfect, so desolate and isolated, in the middle of California? The horizon is marked by spectacular rock sculptures and relics of an earlier time — perhaps a time when lizards were one thousand times larger than they exist today. Every surface is broken and mangled. The trees create arms frozen by an advanced stage of arthritis. Bodies are no longer perfect, but look as though they are altered by the wondrous world where everything that you know seems to be questioned and disfigured.

MC: What are your other favorite films?

LM & KM: We love all Nagisa Oshima films, especially The Ceremony; all Ozu films, especially Equinox Flower, Late Spring, Early Summer and Floating Weeds; It’s a Wonderful Life, Fast Times at Ridgemont High, Who Can Kill a Child, Frankenstein, The Beyond, Halloween, Blood Feast, Suspiria, Vampyr, Night of the Living Dead, Dawn of the Dead, Day of the Dead, Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Dracula, Opera, The Fearless Vampire Killers, The Innocents, Last House on the Left, Audition, White Zombie, Near Dark, The Mask of Satan (aka Black Sunday), Bay of Blood, Eyes Without a Face, Black Sabbath, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, Blood and Black Lace, Profondo Rosso, Horror of Dracula.

MC: What was it like designing the costumes for Black Swan?

LM: We met with Darren Aronofsky in Brooklyn after Natalie Portman suggested that we would be a good fit for designing costumes for the film. We prepared for weeks before our first meeting, researching the ins and outs of the ballet world and the history of its participation in the discussion of voyeurism. Darren had an amazing vision for the film and asked us to custom-design a modern era Swan Lake ballet and specific pieces that would be integral to building the aesthetic for the film. It was an intense and incredible undertaking.

KM: No matter what beauty the audience longs to see, there is still the brutal training, body disfiguration and backstage reality that makes ballet so complex. The story of Swan Lake unfolds as a tale of the transformation of the maiden into a swan and then mutates again into a tale of mistaken identity. The dark and extremely beautiful transformation in Swan Lake mirrors the physical transformation that the ballerina undergoes in order to perform. We were inspired by the idea of transformation, specifically the dichotomy between perfection and decay. For the Black and White Swan tutus and the romantic Maiden tutu, we used fabrications such as embroidered vinyl, layers of hand-applied feather and Swarovski crystals, silk chiffon, silk nets and woven organzas, in order to make the costumes look perfect and yet ruined. The Maiden and White Swan tutus were designed to look delicate and downy. They represent the gossamer, ethereal swan. The Black Swan tutu is more menacing and linked to Von Rothbart. We imagined that these characters would be similar and visually connected to each other; we envisioned them as broken mechanical birds that are in disguise. Von Rothbart developed into a completely black creature, and Odile’s face we hid under black net. The shredded cape of Von Rothbart was made from pulled wool and covered in layers of green and black iridescent feather. His breast was padded out and his shoulders enlarged. We built the Black Swan crown and Von Rothbart demon horns from burnt copper.

MC: What was it like working with Catherine Opie and Alec Soth on your book [Rodarte Catherine Opie Alec Soth, 2010]? How did the creative processes differ?

KM: Cathy shot long-term subjects like Idexa, Jenny Shimizu, Kate Moennig and friends of ours like Guinevere van Seenus and Susan Trailer. She shot each subject against a backdrop of a specific color, and we worked to pick pieces from our collections that would interact with the colors being chosen. Each portrait conveys an intense sense of intimacy with the subject, which only a Catherine Opie picture can do. Cathy worked separately from Alec, but there ended up being a real tangible dialogue between the works.

LM: Kate and I made Alec a list of all the things that inspired us in California and he spent two weeks on a road trip photographing them. We felt that the landscape of California was pivotal in telling the story of our clothes. It was interesting because he was asked to document things that interested us and have influenced our creative process and aesthetic — this is how we got to know one another. It was as if we were pen pals. We titled the book Rodarte Catherine Opie Alec Soth because, in the end, all of our work resulted in a narrative.

MC: Where does the name Rodarte come from?

LM: Rodarte is our mother’s maiden name. Her mother was from Italy and her father from Mexico. She spent her summers visiting her family in Mexico. They would climb the pyramids and she was enthralled with the night markets that were lit by white lights and dancing calaveras and sugar skulls. She loved their white bodies and colored outfits, and how macabre the whole world turned when evening came. She would snack on rock quince in soda, and candied quince sliced up. She remembers going into town to watch movies projected on the store walls and drinking Coca-Cola. On their way home they would buy tortillas and eat them out of baskets. She was in Mexico City during the student riots [1968] and at an early age discovered art and politics. She loved Diego Rivera murals.

KM: As a child, she would sneak into her brother’s room, who was an intellectual, and steal his books: reading books like Siddhartha, Brave New World, Animal Farm, Candide and Sartre in his closet — all the while skipping school and eventually having to hide from her angry parents by covering her face in her mother’s theater powder and pretending to be a ghost under her bed. She was obsessed with books and decided that she would read every book in the library. She started at A. Instead of playing with kids of her age, she would visit all of her elderly neighbors in the afternoons. She decided early on what arts she wanted to accomplish. Our mother is an artist who did Navajo weavings, pottery, mosaics, painting and sculpture. Our dad built her a Navajo loom that reached the ceiling. She used onion skins, turmeric, walnut hulls and moss for dye. She loves the Coit Tower [San Francisco], and to this day, its architecture and displays of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) work has most influenced her artistically.

MC: Where did you get your first names from?

KM: I was named after Katharine Hepburn.

LM: My middle name, Jacqueline, was after Jackie O. The Laura part came from my mother’s childhood neighbor, Laurel. Laurel was quite the klutz, and it became a running joke in the family, that whenever something was broken or was misplaced, they would say, “Laurel did it.” I was an accident so that’s why I got the name.

MC: What about Mulleavy, your last name? Where does that come from?

KM: Mulleavy is our dad’s last name. His first name is Perry. He is from Sierra Madre, California, and grew up at the base of the canyon of Mount Wilson. Mount Wilson is where Hubble discovered that the universe is infinite.

LM: He attended Pasadena Community College and went to classes in a corduroy professor’s blazer, shorts and flip flops. One semester he took a botany class and realized he was good at it, so he went on to study plants, in particular fungi. He went on to receive his PhD in Botany from UC Berkeley and has even discovered species of fungi.

MC: What about your dad’s parents?

KM: My dad’s mother’s name is Nancy Hall Perry. She always talked about one of three things: the boarding school that she attended; her sister Martha; and Sierra Madre. She would take endless walks.

LM: William Mulleavy, our grandfather, was a lieutenant colonel and worked in ordnance during WWII. When he would visit, he would disappear for a day at a time, and when we would ask where he had been, he would reply, “I went for a walk.” He was a traveler, an explorer. He would take a military cargo plane, a Learjet or even a bomber to go anywhere in the world. He never had a plan, but always ended up somewhere.

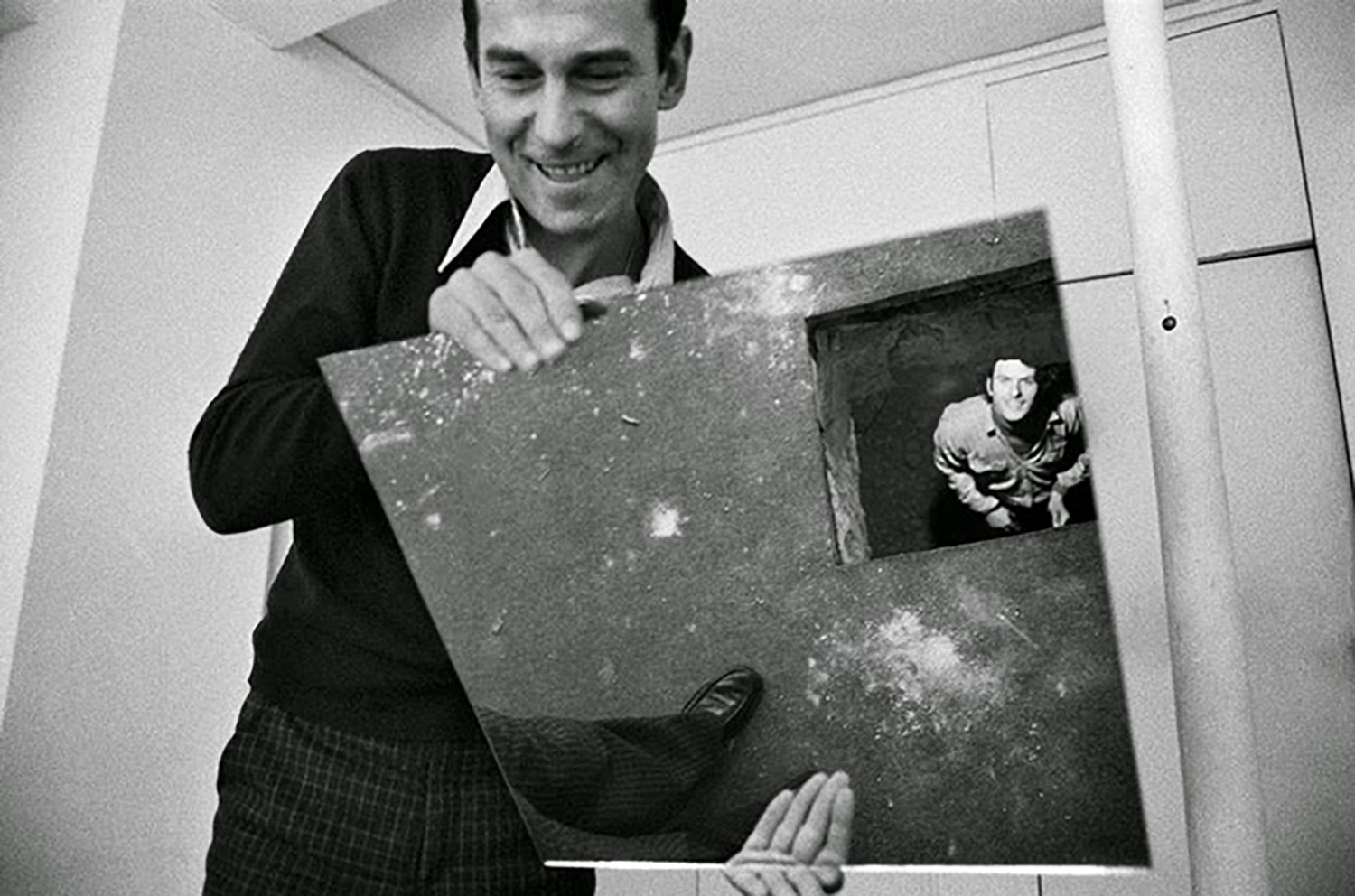

KM: When our grandfather built their family home, he constructed a small box in the corner of the ceiling. For his entire life, he told the family that he put a treasure inside and that when he died they could open it up.

MC: What was in the box?

KM: Guess.

MC: Liberty, opposition, violence, eternity.