Peter Eleey: When you talk about your work you put a lot of emphasis on the variability of the context and the form.

Robert Barry: Less and less. I used to think about that years ago, but I find that as I’ve gotten less political in my work, I am less concerned about the actual context of where it is going.

PE: Did you ever consider yourself a political artist?

RB: If something concerns me — like the Vietnam War, some terrible injustice — a word selection or something may come into the work. I don’t consider myself a political artist at all, but sometimes what is on my mind may influence the context. It is all intuitive.

PE: So many of the earlier word pieces seem to be descriptions of the very process of making them — I’m thinking of pieces like Something that is searching for me and needs me to reveal itself (1969).

RB: Someone said they were definitions of art.

PE: But they also have some connotation of you actually sitting in a room, trying to wait for those things to come. That’s also how the word lists feel.

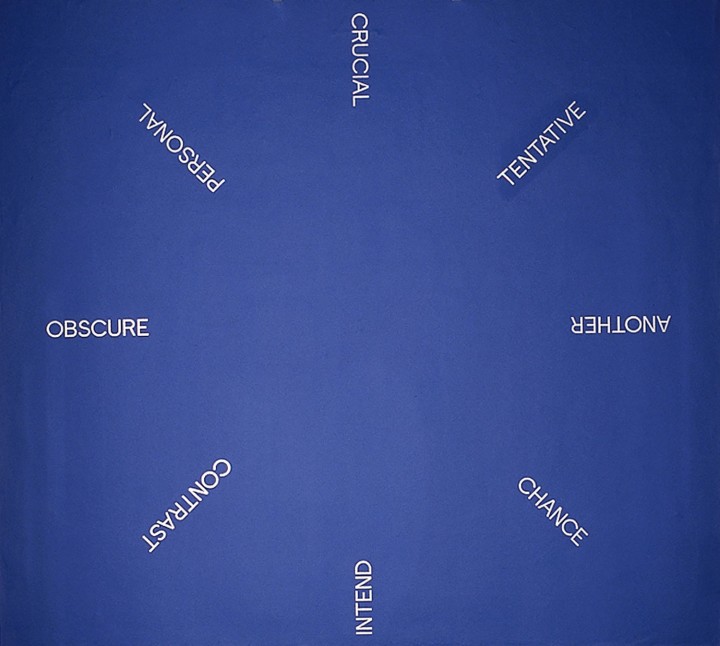

RB: Things develop out of other things; there is no logical process. The ideas are basically suggested, from my own work or maybe whatever I’ve seen around. An idea will just strike me as something that is useable. The idea of just typing something out, or making lists, was a way of getting away from color, getting away from the “arty” look. The thing that conceptual artists didn’t make paintings is bullshit! People have been making paintings for 40,000 years! I use paint all the time, anyway, to paint the words.

PE: Sometimes you seem reticent to explain how your work functions in your mind. Why is that?

RB: I think there is an aspect of the unknown to all of our activities, and attempting to explain it, takes away from what it’s about. I find that explanations are very incomplete. I’m still struggling with the mystery of art. The more I think about it, and the more I think I know something about this process that I’m engaged in, the more I realize that I don’t.

PE: Is emotion part of your work, or how you make it?

RB: The emotional component is important. You can’t just rely on ideas, or play with various art strategies. But I tend to not use the word “emotion” anymore. I like to say “engagement,” which is usually an intellectual-emotional combination.

PE: But is the audience something you actively think about when you are conceiving of a work?

RB: You do put your work out into the public. But that’s about it. I like words because people can relate to them — but what they do with them afterwards is not in my control. It is kind of interesting to see the reactions that you get from other people, other artists. But it has nothing to do with the actual form, the look, or the direction of my work. In a lot of my work, I’m trying to make it slightly difficult for people to come to it, to deal with it in any traditional way.

PE: You were much more ambivalent about the audience at one point. I’m thinking of your text for “Prospect 69,” where you say art is about making art, and it is not about people being aware of art.

RB: I did that in the telepathic pieces, and I’ve done performances and sound pieces that are trying that out. It is really directed towards people out there, though I don’t know who, and obviously can’t control how people take it. A lot of artists have texts accompanying their work that specifies how the work should be experienced. But when you do that, you really limit the work.

PE: What about people like Robert Smithson, who wrote a lot alongside their work?

RB: I’ve always loved Bob’s work, but I thought the primary reason people read his writing is because curators and critics, who like ideas written down because it gives them some kind of entry into the work, read it. I don’t need that. We kind of got friendly but Bob and I had lots of problems. He was very anti-conceptual art. He thought it was all about ideas, and I tried to explain to him that it’s not. I deal with both physical things and ideas. All art is physical.

PE: So does that mean that the unknown can have a physical form?

RB: Yes, absolutely. A very physical form. But it may be in your mind. Dealing with the unknown, you are heading into that area of the physical and mental, which has dogged philosophers for a long time. Artists understand it, philosophers don’t. They are constantly trying to explain it. Artists just accept it.

PE: Certain works of yours insist on being in an unknown space outside of consciousness, and they are qualified by the prescription that they expire once they become known. When you’re making work that erases itself the instant it can be apprehended, you’ve sort of painted yourself into a corner. How do you make art after that?

RB: You never paint yourself into a corner. When Ad Reinhardt made those black paintings, this was an issue. But then we came up with conceptual art. There is always a way out. It was about the unknown, and about putting that very condition out there, so that people would have to deal with it along with us. I always said that whatever the meaning of the art is, it’s left up to the audience.

PE: But you have always resisted the term “mystical.”

RB: Yes. I mean that in a religious way. And I am not a religious person. It’s a loaded term that has too much to do with God, or hippies, and whatever — or at least it once did.

PE: Sol LeWitt, though, has that great line about how conceptual artists are “mystics rather than rationalists.”

RB: Did Sol really say that? He would never go back and say so, but I think he regretted saying those things. I understand the intuitive aspect of thought, and the irrational, but I also respect scientific thinking and logic as ways of understanding the world.

PE: When you talk about all art being physical, does this mean you see yourself as a sculptor?

RB: No, not at all. [Lawrence] Weiner believes that all art is sculpture, but I disagree. I think those terms are limiting. I do think of everything in terms of space, but I just prefer to call myself an artist.

PE: Who among your contemporaries did you feel closest to? I’m thinking, for example, about the piece you did where you photographed the length of a river in 1972, which is a very similar thing to what Douglas Huebler was doing.

RB: I’ve always liked Larry’s [Weiner] work and [Joseph] Kosuth’s work, and also Bob Ryman and Sol [Lewitt]. I never thought about that comparison to the river piece, but I always felt that Doug [Huebler] was a little late to the game. I was very sensitive to picking up on other ideas, but I never felt I took anyone else’s ideas. It was always important to me to be individual; there was a lot of good conversation about where the thinking was going in terms of art. There was zero money, nothing was selling, so there wasn’t any competition and it was very free-floating and open.

PE: You once said that art allows us into some other realm that science and philosophy can’t reach. Did you mean that because of art’s assumption of visuality, it can model the unknown for us in a way that science and philosophy cannot? That the implicit engagement with looking can be used, removing the subject in order to provoke a search for it?

RB: I think it is about luring someone into exactly that search. I’m trying to find the most basic things, like space and time, because I want it to be accessible and available.

PE: How did you first begin to work with invisible materials, like carrier waves, radiation and gases?

RB: I know I did a carrier wave piece between New York and Brussels, but I don’t know if this was it. There was a friend of mine, a student, who was a ham radio operator. He’d turn on Radio Moscow or whatever, and the transmitters were so powerful that it would take 20 minutes or so to warm up, blotting out everything on that wavelength, so it was just complete silence until the voice came on. I decided later that this was a way of dealing with space and time that was not normally thought of. If you follow this path of minimalism — reducing the means, dealing with space — the element of time comes into your work. The idea of the inert gas pieces came from having studied it in high school, and it just stayed in the back of my mind.

PE: If you are making work about basic things like space and time and their limits, aren’t you also in some sense making work about death?

RB: Yes. Absolutely. It is not something you can avoid, and it is a very mysterious thing. Dying and also making work about dying — these are things I’m not going to deal with “mystically” or religiously.

PE: How did your Closed Gallery project come about in 1969? And were you aware of those done by James Lee Byars, Graciela Carnevale and Daniel Buren around the same time?

RB: I didn’t know Byars did one, or anyone else, though later I became aware of Stanley Brouwn’s empty gallery pieces, which were something different. I knew of Daniel’s closed gallery piece at Wide White Space in Antwerp, but he used his striped posters over the doors, running out into the street. I wanted mine to be absolutely direct — close the damn place, send out the mailer and say the gallery is closed. As the three galleries did it, I changed the way it was said so there was just a slight variation between them. But I didn’t even design the mailer. I just had them do it in their typical format.

PE: How did the closed gallery projects function in the context of the other works you were doing at the time?

RB: I wanted to use the gallery space as a material. Similar to what I did when I did that piece with Lucy Lippard, but I wanted to reverse the roles. It was her show at Yvon Lambert in 1971, in which I showed her catalogues and writings.

PE: So closing the gallery was removing the subject the same way you had in other works.

RB: Yes. Using that kind of negativity or nothingness. Contradicting the nature of the gallery and what it is used for. They were really closed. The doors were locked.

PE: This is an ambivalent relationship with your audience: you want them to engage with the work, but then of course if they came to the gallery they were literally locked out.

RB: Not really. I think my feelings about the audience are pretty direct. It was a challenge. Sometimes people get angry with you when they get to the gallery and they don’t see anything. But there is plenty there for them to grasp, even if it is just the emptiness, or the space between things. All this work came out of thinking about the basic fundamentals of what art is really about. Conceptual art dealt with those things. It was about how art interacts with the rest of the world.

PE: Is that why you intended your early paintings to have an expanded spatial field, to make the space between them part of the work?

RB: Yes, that was about using the context. But it wasn’t just my idea. Mondrian seemed to think of the paintings as complete things in themselves, but then he never seemed to be finished with them. There was always a line that would wrap around a corner, or a line bleeding through the white; parts that seemed to complete themselves outside of the canvas. I used to go to The Cloisters with my father on Sunday, and they would play Gregorian chants, and it would reverberate around the space in a way that became part of the room. I think I recognized it even as a kid. And remember that when I was a student the frames were getting thinner and thinner anyway.

PE: When looking at your recent work, the thing that feels most consistent is the continued importance of space, and how important language is in the construction of that space. How else do you see your early work connecting through to your current interests?

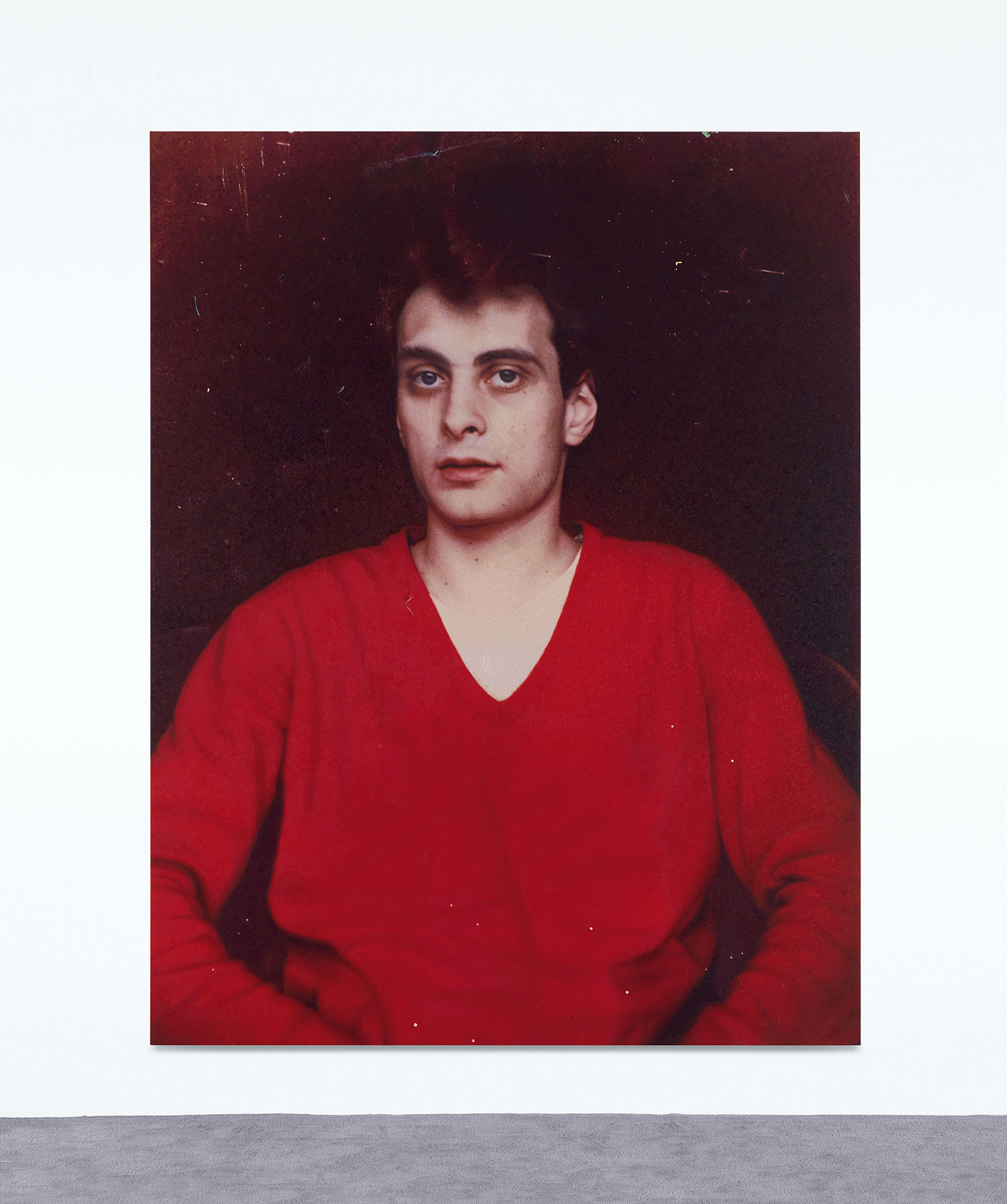

RB: I think my recent work has become more personal. By that I mean I’m working with the actual place of the gallery or museum. It’s more about me or anyone being in the particular place at that time. I said art was something physical. It’s also conceptual and emotionally engaging. Lately I’ve been doing some pieces I call “old work presented in a new way.” An example is the old telepathic pieces which used to be shown simply on a page in a catalogue. Now they are on the wall, a part of the environment. More physical, more colorful, but still in your head.

PE: That emphasis on the actual place of the gallery you mention makes me think of your early work outdoors, which seemed like a natural progression in your initial efforts to engage a broader physical space. Were the monofilament pieces the first things you did outside the gallery?

RB: The first were actually these white cubes I did out in a field in 1967. They were kind of an extension of the paintings I did with these four squares on the wall. Then I did another sculpture like that, then the monofilaments, and then the inert gas works.

PE: You would consider the inert gas pieces outdoor works?

RB: Yes, and the radio wave pieces, too.

PE: Even if the radio wave pieces were done indoors?

RB: They aren’t “done.” Look, you “do” them, but they only start there, and they go out beyond infinitely. Some of the radiation pieces were done indoors and others outdoors. I thought of the whole universe.

PE: So inside and outside cease to be different contexts?

RB: Not quite. I was always aware that FM radio bounces back in off the atmosphere, so it wasn’t totally infinite. AM shoots out into the universe, as does television. My father was an electrical engineer, and he made the first of my radio wave pieces with me. We went to Radio Row, which is where the World Trade Center was eventually built, and we bought the parts there. I was always fascinated by the space of radio.

PE: The radio is a nice metaphor for so much of the way you approach your art. The disc jockey addressing some unknown audience, not knowing what is actually making it over the airwaves, and whether anyone is even listening.

RB: Isn’t that true of all art? Artists never know how their work is received.