In The Misandrists (2017), a term meaning “hatred of men” (the sisterly opposite of “misogynist”), Bruce LaBruce (b. 1964, Canada) takes on an unexpected sexual and political challenge. His “misandrists” are a secret cell of feminist terrorists planning to liberate women, overthrow the patriarchy and usher in a new female world order. German actress Susanne Sachsse pulls out all the stops as Big Mother, the platinum-wigged, crippled directress of the terrorist cell, who must protect their secret from the outside world and maintain its cover as a school for wayward girls, even donning full nun’s attire when discovery of the true purpose of the group is threatened. When a wounded young man, a radical leftist running from the police, appears nearby, one of the girls hides him in the basement. Warning: Watching what eventually happens to him should be avoided by all those who feel faint of heart when watching medical procedures.

The phallus makes an occasional appearance in The Misandrists, echoing all of the director’s former, mostly gay-male-oriented films, but this new work places itself squarely in the camp of “pussy power,” as LaBruce terms it. As is his wont, he expertly treads the dangerous line between the ludicrous and the politically serious, pandering to the “male gaze” yet audaciously subverting it at the same time.

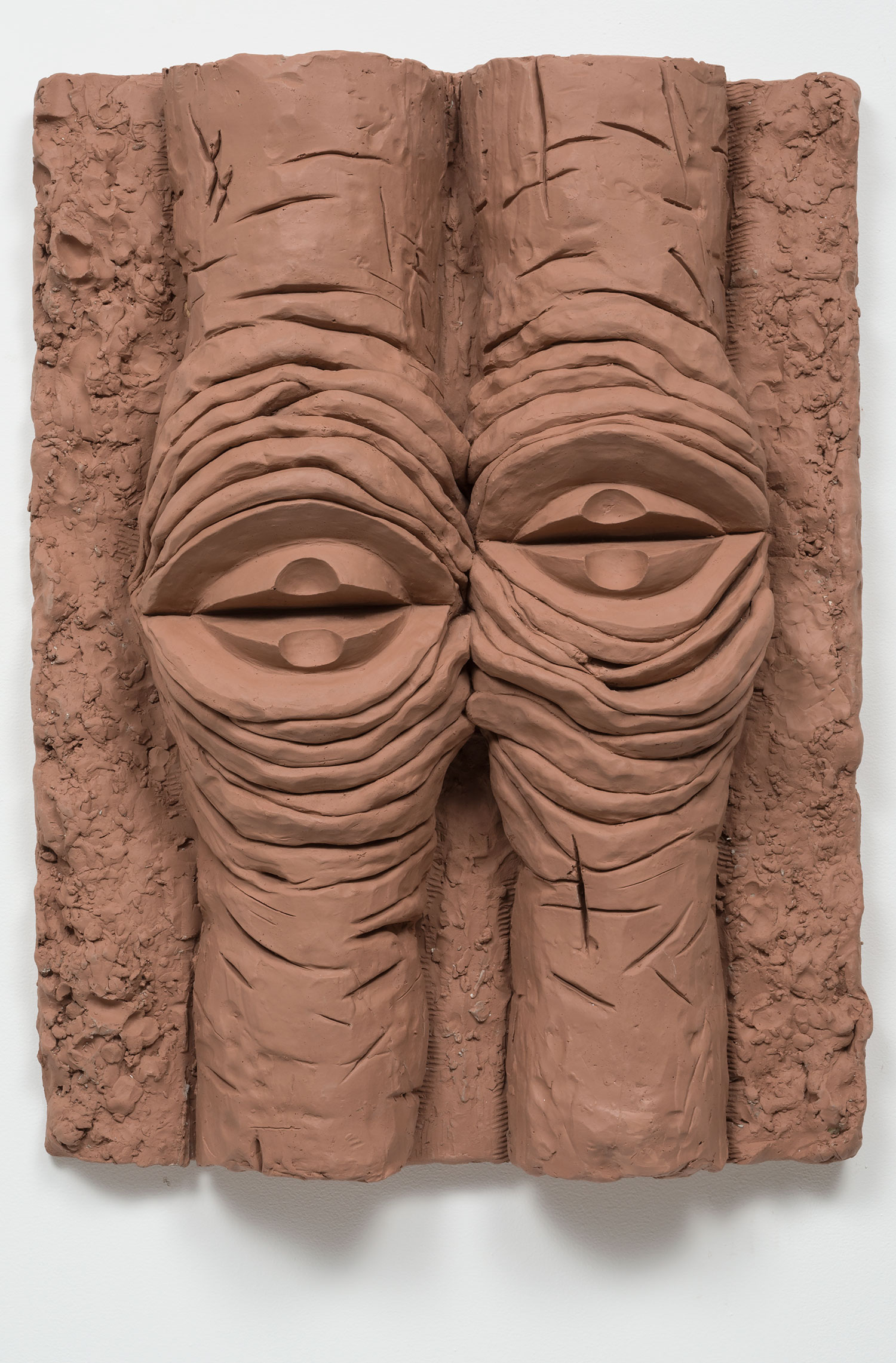

Anyone interested in the erotic attractions of the female body won’t be disappointed watching LaBruce accomplish his minor miracle. He uses pornography and its blatant associations with exploitation to promote a radical essentialist feminine agenda — based on biological determinism and harking back to Simone de Beauvoir’s seminal The Second Sex, which connected the female body and brain with Mother Nature, Mother Earth and the goddess of fecundity.

Keeping such elements in mind, The Misandrists, actually a critique of the assimilationist elements of Second Wave Feminism, seems to promise something to offend everyone. Instead it becomes a delightful romp through the confusions, controversies and media distortions of today’s rapidly mutating gender discourse.

Bruce Benderson: A repeated prayer from The Misandrists is “Blessed be the Goddess of all worlds that has not made me a man.” Why this wording, when all they needed say was “…for making me a woman.”

Bruce LaBruce: This quote is a direct inversion of an Orthodox Jewish morning prayer that says, “Blessed be the God of all worlds that has not made me a woman.” If the prayer were “that has made me a man,” it could mean as opposed to a dog or a rock, for example. But it specifies a woman as, presumably, the most horrendous incarnation that they could imagine. So I’ve just turned the tables.

BB: From what I can tell, female identify in the film relies on two familiar worldviews that are far from independent of “the patriarchy”: women defined as what they are not, not being a man — a lack, in other words — which is exactly how Lacan defined woman. And secondly, women defined in terms of their role in nature, “the feminine principle.” Aren’t those two positions awfully close to patriarchal formulations?

BLB: Not in my estimation. In my configuration, the misandristic women are attempting to eliminate the male of the species altogether, ideally through asexual reproduction (parthenogenesis!), in which case they would not be defined by lack because there would be nothing lacking, nothing to envy, even if it were enviable, which it isn’t. In the words of Big Mother, they exist “in anticipatory celebration of a world in which men not only will become surplus, but also redundant.” They want men to be taken out of the equation altogether. Essentialist feminists argue that the world and nature are fundamentally female, and that civilization, created and controlled by the male, has always been an epic struggle against it. The misandrists believe in tulip power — two lips, the vagina.

BB: “Ulrike’s brain” appears in two of your recent films, both The Misandrists and the eponymous short Ulrike’s Brain (2017).

BLB: Ulrike’s Brain is a fifty-minute experimental, stand-alone film that also appears briefly as a film-within-the-film in The Misandrists, referencing the brain of Ulrike Meinhof, the infamous RAF terrorist, which, after her death, was studied, stored at Heidelberg University, and then disappeared. In Ulrike’s Brain, Susanne Sachsse plays a mad doctor who has the brain and is trying to find a female body to transplant it into to start a new feminist revolution. In The Misandrists, Ulrike’s Brain is identified as the only movie that Big Mother, a former actress, appeared in under her real name, Gertrud Stammheim, before she became an academic. Big Mother is a kind of tribute to Ulrike Meinhof, who started out as an academic before becoming an extreme left-wing terrorist.

BB: The film takes place in 1999, and you’ve stated that you set it in that period because it existed before second-wave assimilated feminism. Is this film a “wake-up-and-smell-the-estrogen” slap in the face to today’s assimilated feminists?

BLB: The Misandrists is completely opposed to the notion of assimilated feminism or “post-feminism.” I was inspired by Ulrike Meinhof’s Everybody Talks About the Weather… We Don’t [New York: Seven Stories Press, 2008], a collection of the monthly columns she wrote for the radical leftist Konkret magazine from 1960 to 1970. Meinhof was categorically opposed to feminist assimilation. She believed that, as Big Mother paraphrases, “Equal participation in an iniquitous society is incommensurate with womancipation.” The fight for parity within a manifestly corrupt, patriarchal system is a fool’s errand for feminists, gays and blacks alike. It’s a failed strategy from the very beginning, only resulting in the oppressed becoming the oppressors, one of my favorite themes.

BB: What gave you the idea to make the school directress, Big Mother, crippled? In fact, “Watch the leg” becomes a repeated gag each time she’s sexually approached by her partner. Does it have anything to do with the line “Watch the leg, Marnie,” spoken by the mother in the Hitchcock film?

BLB: Of course it does! Marnie (1964) is a sacred text! As we all know, a broken or amputated leg is a classic symbol of castration, perhaps most famously used in Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954) and in Don Siegel’s The Beguiled (1971), the latter of which The Misandrists is a loose remake. In my movie, I parallel the injured leg of the heterosexual male fugitive that Isolde has locked in the basement with the permanently injured leg of Big Mother. Of course he ends up “castrated” in the sense that Big Mother performs involuntary sexual reassignment surgery on him, just as the Geraldine Page character in The Beguiled amputates Clint Eastwood’s leg as an obvious symbol of castration. (But the short answer is that my leg was broken while I wrote the script. In fact, Susanne Sachsse as Big Mother wears the very hi-tech leg brace that I wore, one of the many purposeful anachronisms in the film.)

BB: One of the central conflicts in this film deals with what happens when lesbian separatists reject trans women because they think they are not real women. What was your purpose in bringing this issue into a film about revolutionary feminists?

BLB: I of course believe that trans women are women and should be accepted as “real women” if that is how they identify. The Michigan’s Women’s Festival was the most high-profile example where trans women were rejected for either having or having had a penis. Certain second-wave feminists like Germaine Greer (whose most famous book, ironically, was called The Female Eunuch [London: Flamingo, 1970]) are still adamantly opposed to accepting transgender people as women. As an affectionate critique of second-wave feminism, I felt The Misandrists needed to address this issue directly. The film challenges this misguided tenet of essentialist feminism by celebrating “femaleness” in all its forms.

BB: You’ve spoken about the irony of a Republican, Caitlin Jenner, becoming an icon of the trans movement. What about those “gender nazis” (if you’ll excuse the term) who claim the left for their identity? Weren’t they the ones, for example, who tried to shut down RuPaul’s TV show for using the term “tranny”?

BLB: One of the cruel ironies of second-wave feminism, which seems to be making somewhat of a comeback, is that some of its beliefs and strategies dovetail perfectly with the extreme right. Issues of censorship, the policing of language, and anti-porn and anti-prostitution postures all correspond way too conveniently with the religious right. In the 1980s, certain radical feminists were known as “Stalinist” because their rigid and authoritarian views and their attempts to control language and behavior contravened freedom of speech and civil liberties. We’re seeing a return to that mentality with some radical feminists and transgender activists today.

BB: Your film was actually my first encounter with the term “misandrist.” To my surprise, a Google search revealed hundreds of URL’s with discussions of misandry. Certain people, however, are questioning it from an ethical standpoint. In her Time magazine article “Ironic Misandry: Why Feminists Pretending to Hate Men Isn’t Funny,” Sarah Begley wrote, “But inherent in this word ‘misandry’ is hatred… If a man wore a T-shirt that said ‘misogynist’ even if he were a dyed-in-the-wool feminist, wearing it tongue-in-cheek, it would not be funny.” Do you agree?

BLB: I read that article while I was making the film. No, it’s a false equivalency. In a way it’s the same reason why you can declare black pride but not white pride, or why you can wear a “honky” T-shirt but not a “nigger” T-shirt, ironically or not. It has to do with social and political context, the weight of history, and, in effect, recognizing and balancing out the historical discrimination and violence against certain marginalized groups. So if one considers the weight of history and the discrimination against, marginalization of, and violence toward women, it’s easy to make a comedy called The Misandrists! It also helps to have a sense of humor.

BB: You’ve stated you were referencing The Trouble with Angels (1966) in this film, and I myself noticed the extended reference to the feather-pillow fight in Jean Vigo’s Zero for Conduct (1933). Were you referencing any other specific films?

BLB: There are more movie references in The Misandrists than even my conscious mind is aware of. We’ve already mentioned several: Hitchcock’s Marnie, Siegel’s The Beguiled, Ida Lupino’s The Trouble with Angels (a great Hollywood lesbian nun film, directed by a woman), and there is also Ulrike Meinhof’s Bambule (1970). The police interrogation scene, in which the twelve females line up for inspection, is a direct reference to Robert Aldrich’s The Dirty Dozen (1967), shot in the same style as its credit sequence. The egg coming out of the vagina scene (which was actually a shot of an egg inserted into a vagina run backwards) is a reference to a similar scene in Nagisa Oshima’s In the Realm of the Senses (1976). I was also referencing, particularly in the pillow fight, egg tango, and orgy scenes, the aesthetics of certain 1970s soft-core erotic films, anything from Bilitis (1977) to Daughters of Darkness (1971) to certain Russ Meyer films. This, of course, is all very non-PC, because these are films with lesbian sex scenes directed by men. But I always thought they were pretty sexy and gorgeous depictions of women. I was also referencing 1970s nunsploitation films, of course.

BB: In discussing the schoolgirl costumes for The Misandrists, you stated on dazeddigital.com, “I was also influenced by Japanese schoolgirl movies, which is a really popular genre in Japan. In terms of the uniforms, I had a very specific idea in mind… It was this half-serious schoolgirl look and half-militant revolutionary look.” What you haven’t mentioned is that some skirts were ripped so high that the girls’ buttocks were visible, making them look more like Balthus had designed them.

BLB: Well, it’s true that I asked our costume designer, Ramona Peterson, to make the girls’ school uniform skirts shorter than she originally proposed them. It was partly a recognition of the genre, and partly because I think it looks good aesthetically. Having said that, I will say that one of the girls ripped her skirt and made it even shorter. I encouraged the girls to embellish their uniforms to make them feel comfortable and to represent themselves how they wanted to be represented within that scenario.

BB: A recurring element of many of your movies involves using blow-up posters of historical figures that relate to the political theme. Which did you use in The Misandrists?

BLB: The blow-up in Big Mother’s bedroom is Emma Goldman’s mug shot, taken when she was wrongly implicated in the assassination of President McKinley in 1901.

BB: Reams have been written about the majority of lesbian pornography actually being staged to excite heterosexual men. Do you feel that you escaped that connection? How?

BLB: I suppose it’s impossible, as a male director, to completely escape that connection. Of course I’m gay, a Kinsey six, so obviously it was more of an aesthetic than erotic exercise for me. But I also believe that everyone is born with bisexual potential, so I’m not ashamed of any erotic feelings that might be aroused by the film. I try to subvert the male gaze in a couple of ways. Firstly, I insert myself in the film as a nun, in drag, as a way of distancing myself from my own gaze, or making it self-conscious, to myself and to the audience. I always use distanciation techniques when representing sex and porn, probably because I’m Canadian. Secondly, the lesbians in the film are making and directing their own pornographic film, and that film, at some point, becomes the film we are watching. So in a sense the characters take over the making of the film. In the final scene, I shoot members of the audience, mostly women, being aroused by the lesbian film-within-the-film, so again the gaze is distanced, but also taken over by female characters. But ultimately I think the film is sexy and I really can’t control who gets turned on by it.

BB: Going back to your uncredited appearance: not all viewers will realize that it’s you, in the tradition of Hitchcock’s appearances in his films. Who is your character supposed to be?

BLB: As I just mansplained, the secret nun is my avatar in the film, in drag, designed to subvert the male gaze. It also creates a hermeneutic that is never solved or resolved, which challenges the conventions of mainstream cinema, a largely male discourse. And it has me sharing the role of Big Mother with Susanne Sachsse, who is my main point of identification, as the director, in the film. The scene when I, as the secret nun, do the Charleston is a direct steal from Stanley Kramer’s Ship of Fools (1965), in which Vivian Leigh, out of the blue, does the same.