Eric Troncy’s text “Being Positive in the Secret of the 90s,” which appeared in Flash Art in 1992, focuses on what the author sees as a tendency toward stifling moralization in art’s reception at the beginning of the 1990s. Eli Diner rereads Trance’s text through the lens of some recent art-world controversies.

In 1992 critic and curator Eric Troncy published an essay in Flash Art called “Being Positive is the Secret of the 90s.”[i] It’s a great title, though not originally his; he’d borrowed it, as he acknowledges, from a 1991 work by Dutch artist Renée Kool: a thick chain necklace made of plywood with the eponymous phrase inscribed in a new-jack-swing kind of font. In the midst of the AIDS crisis, being positive, of course, had a more ambiguous sense, but Troncy does not concern himself with this meaning. Instead his essay focuses on what he sees as a stifling moralizing in art and in the reception of art at the beginning of the final decade of the twentieth century. It’s an odd text and not altogether cogent, yet the themes he touches on — sometimes clumsily — remain absolutely central to art, capturing some of the often-acrimonious divisions twenty-five years hence. Even as Troncy renders his subject simplistically, obscuring critical and political stakes in favor of a facile framing in terms of positivity and negativity, a reading of these confusions and elisions actually helps elucidate some of the contradictions around art in our moment.

Troncy begins with a measurement of distance: the twenty years since Joseph Kosuth’s claim that “works of art that attempt to say something about the world are doomed to failure.” The quote, so far as I can tell, is apocryphal, but the point in unmissable: now the work of art must say something about the world; and increasingly that something, Troncy laments, takes the form of the denunciation of injustice or exploitation. Taking a position on a given political issue becomes the essential feature of many works of art in the 1990s. This art of “moral advice” suffers, according to Troncy, from naïveté — ultimately reducible to a simple calculus of good and evil, a recipe for the uninteresting: “One thing about good intentions is that they make absolutely everything legitimate.”[ii] This moral code accounts not only for work made by those he marks as “committed artists,” but also for Benetton ad campaigns and Jeff Koons’s “Made in Heaven” series. Maybe worse than the moralistic art itself is the response to those things seen not to fully conform to standards of decency or deemed to not come down decisively on the side of good. He cites the example of the controversy in France over Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho (1991), regarded as abhorrent because “at no point does the reader feel that the author is condemning the murderer.”[iii] Or compare the critical enthusiasm for Renée Green with the condemnation of Rob Pruitt and Jack Early: while Green’s didactic installations explicitly focus on the critique of racism, Pruitt-Early’s controversial 1992 show at Leo Castelli, “Red, Black, Green, Red, White and Blue,” which involved a vast collection of found posters depicting black people (musicians, athletes and political heroes together with some kitsch Africana), was ambiguous as regards intent, “speak[ing] in terms of the simple facts of culture without really revealing their stance.”[iv] Here things get a little fuzzy, but I think Troncy is, in his final move, trying to say that such neutrality is fundamentally at odds with the reign of positivity in the 1990s, that even those critical or denunciatory works of “committed” art are, in the final analysis, positive — rather than negative — because they are incontestably right-thinking, because they conform to the dominant moral code, and thus condemnation is rendered affirmation of the good against the evil.

When he wrote the essay, Troncy was fresh from having organized “No Man’s Time,” an exhibition at Villa Arson in Nice the previous year, which has subsequently been recognized as an epochal contribution to what would come to be known as relational aesthetics. Describing his intentions in the pages of Flash Art, he wrote: “‘No Man’s Time’ has been based on no particular concept and is without any theoretical scheme. First and foremost, the show does not set out to prove or claim anything. It is neither an angle on the future nor a synthesis of the present. ‘No Man’s Time’ is a show and its three-month duration is not unlike a theater run.”[v] There’s that prized “neutrality” again, fused with an appreciation for spectacle. But as Claire Bishop has argued, “At stake in this shift — from a group show organized around a theme, to the creation of a project that unfolds in time — was a position of authorial renunciation… This desire for open-endedness formed part of a generational value-system that rejected prescriptive meanings tout court; for Troncy, [Nicolas] Bourriaud and their collaborators, open-endedness stood against the closed meanings of critical art in the ’60s and ’70s.”[vi] Of course, Troncy issued his condemnation of positivity in the midst of a global recession and a reeling art market, and it too can be read as a rejection not only of the — presumably stale — formulae of critical art, but also of the bland market-driven excesses of the 1980s.

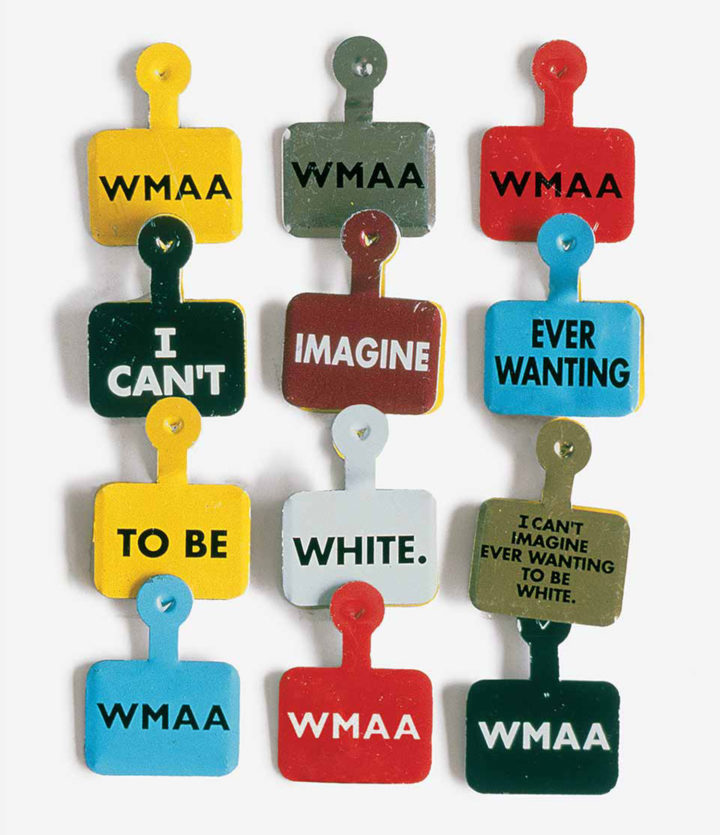

The question remains: Is Troncy’s assessment of art in the 1990s a good one? The Whitney Biennial the following year — one barometer of American art — went down as the political one — or perhaps more properly the identity politics one — for its increased number of artists of color and women artists, and for its preponderance of work addressing questions of race, gender, imperialism and AIDS, inter alia. But does this affirm Troncy’s reading? Let’s accept, for the sake of argument, that the apparently negative operates under the aegis of the positive — that, for example, Daniel Joseph Martinez’s emblematic contribution to the Biennial, admission badges handed out to each visitor that read “I can’t ever imagine wanting to be white,” really want to say “I am happy with who I am” or “I’m proud to be Latino.” But if so, then what explains the vicious critical response to the exhibition? The vitriol from Peter Schjeldahl, Michael Kimmelman, Hilton Kramer and the rest puts the lie to — or at least complicates — the notion that there was a single dominant liberal moral code shared by all parties in the art world.

The notion that there is such a consensus and that it exercises a determinant — or perhaps muzzling — effect, whether in the art world or, more importantly, at universities and in the media, is a well-known right-wing boogieman. At the time Troncy wrote his text, this phantom had only just seized the American conservative imagination, in books like Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987), while even more recently, at the dawn of the 1990s, it had assumed the now familiar name of political correctness, a conspiracy theory deployed to apparently great effect by Donald Trump. And though we can’t hold this against Troncy, his attempt to stake what appears to be a middle ground in the culture wars leaves him seemingly open to a range of accusations.

The controversies across the art world in recent years demonstrate that, as in the 1990s, there is hardly any uniformity of opinion. If anything, ideological tensions appear to be heightened — a state of affairs that predates the election of Trump but which, no doubt, has been exacerbated in the United States by the hateful rhetoric and divisiveness of his presidency. On the one hand, the dustup over Kelly Walker’s exhibition at CAM St. Louis, in fall 2016, suggests that maybe the kind of neutrality that Troncy outlined does indeed have the power to evoke the forces of moral outrage. Like Pruitt-Early, Walker appropriates images of black people with an indecipherable deadpan — “the simple facts of culture” plus toothpaste. And yet the many calls for the show to come down were met with at least as many for it to stay put. Though the curator resigned in the wake of the outcry, and the museum threw up some extra walls and a trigger warning outside the show, Walker’s exhibition ran not a day short of its planned course.

So, there you have it: we wouldn’t see this succession of controversies — over Dana Schutz, Sam Durant, and Jimmie Durham, in Boyle Heights and in Chinatown — if we had anything close to a consensus. The great accomplishment of Hannah Black and company was to expose the hollowness of the claims of unity and community that so many rushed to make on the eve of the 2016 Whiney Biennial, the agreement in advance that we would all like this one, that it would be a sign for us, of our resistance — because we needed it now, we needed to come together. Who’s this us you speak of? they seemed to say. Which community is that?

And yet, one of the more remarkable features of these controversies has been how, quite often, the lines are drawn within a very narrow ideological patch. In Minneapolis, the protesters won the day, and Durant eagerly agreed to the dismantling and burial of his sculpture Scaffold (2012) by representatives of the Dakota Nation. All parties shared a condemnation of the execution of thirty-eight Indians during the Dakota War of 1862 — and, more generally, of America’s genocidal extermination of its indigenous populations — but Durant had not considered that some would find his scaffold offensive and did not, in the end, want to offend anyone. In the Schutz affair, the painter set out to paint an obviously anti-racist painting, which turned out, in the eyes of her detractors, to be racist because that was not her painting to paint. That’s a comparatively thin wedge: the question of who’s allowed to paint the anti-racist painting.

We expect a lot of our museums. We want them to reflect us and our political and ethical commitments. We want them to be safe spaces. The protests over the occasional failures of these institutions to regulate aversion, to exclude that which we find offensive, suggest that perhaps there is an overarching positivity in the ideology of diversity, manifested in the belief in the perfectibility of the art institution. By contrast, the role of these museums as mechanisms of the capitalist class, their function in valorizing the investments of trustees and collectors and in giving cover to corporate benefactors, is seen as inconvenient but the sort of thing that only bothers Andrea Fraser and other miserable old practitioners of institutional critique. Hardly worth mentioning. As it happens, Trump, who staffed his cabinet with museum board members, is surrounded by these kinds of art lovers — Ivanka, of course, but also Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin.

Midway through his essay, Troncy suggests that the pervasive moralism of so much art of the early 1990s functioned like penance for the sins of vapidity, luxury and high auction prices. We are now, somehow, condemned to relive both decades simultaneously — the inescapable influence of the hyperactive market and its taste for insipid fare and the profusion of high-minded bien pensant art. The two, it turns out, live quite happily together.