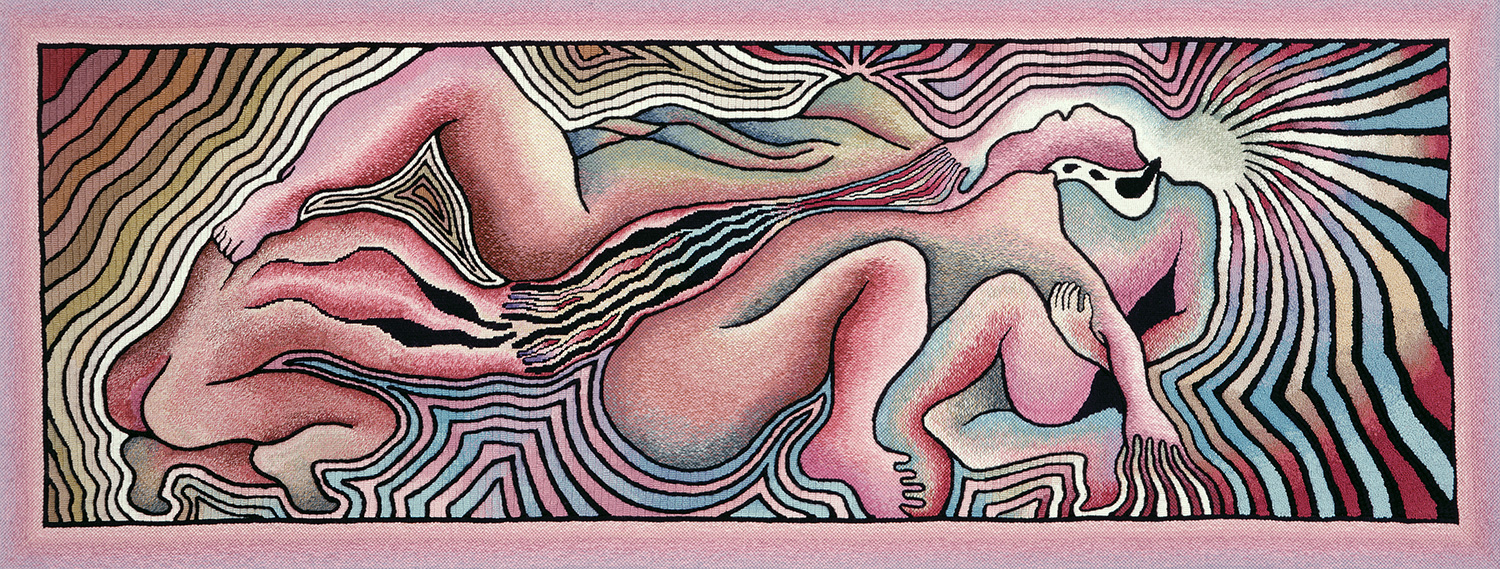

I first saw Judy Chicago’s Birth Trinity (1983) and Birth Tear/Tear (1982) when visiting the artist’s studio in Belen, New Mexico, in 2017. In brightly colored needlework and at vastly different scales, this pair of works depicts voluptuous female figures distorted by the pain and joy of childbirth. The pieces are part of the artist’s Birth Project (1980–85), a series of eighty-five needlepoint and textile works and one large-scale drawing, all containing images of pregnancy and birth. The elements encompass various motifs, such as “the creation,” “the crowning,” “birth goddess,” and “birth tear,” that illustrate the lived realities and mythological facets of giving birth. Birth Trinity, a needlepoint piece of impressive size, is a stylized portrayal of a woman in labor: she is split in half and sunbeams rise from her head; a human figure kneels between her splayed legs, seemingly flowing out of the center of her body. Lines of pink, blue, and yellow emanate from her body and breasts. The whole figure pulses with color and energy. Birth Tear/Tear is much smaller. On crimson silk, delicate embroidery forms the image of a female body ripped in half from her vagina up to her neck; pain distorts her face, as lines from darkest red to brightest pink radiate from her body. The delicacy of the material stands in stark contrast to the brutal pain depicted in the image.There are very few works of art depicting birth. Childbirth is a foundational process, yet it is typically kept hidden, suppressed or only hinted at rather than overtly portrayed. This has remained true throughout much of the history of Western art. Indeed, when Chicago started working on Birth Project in 1980, she expressed surprise at the scarcity of birth imagery in art: “There were some photographs, but these were scarce. And when I scrutinized the art-historical record, I was shocked to discover that there were almost no images of birth in Western art, at least not from a female point of view. I certainly understood what this iconographic void signified: that the birth experience (with the exception of the birth of the male Christ) was not considered important subject matter.” 1

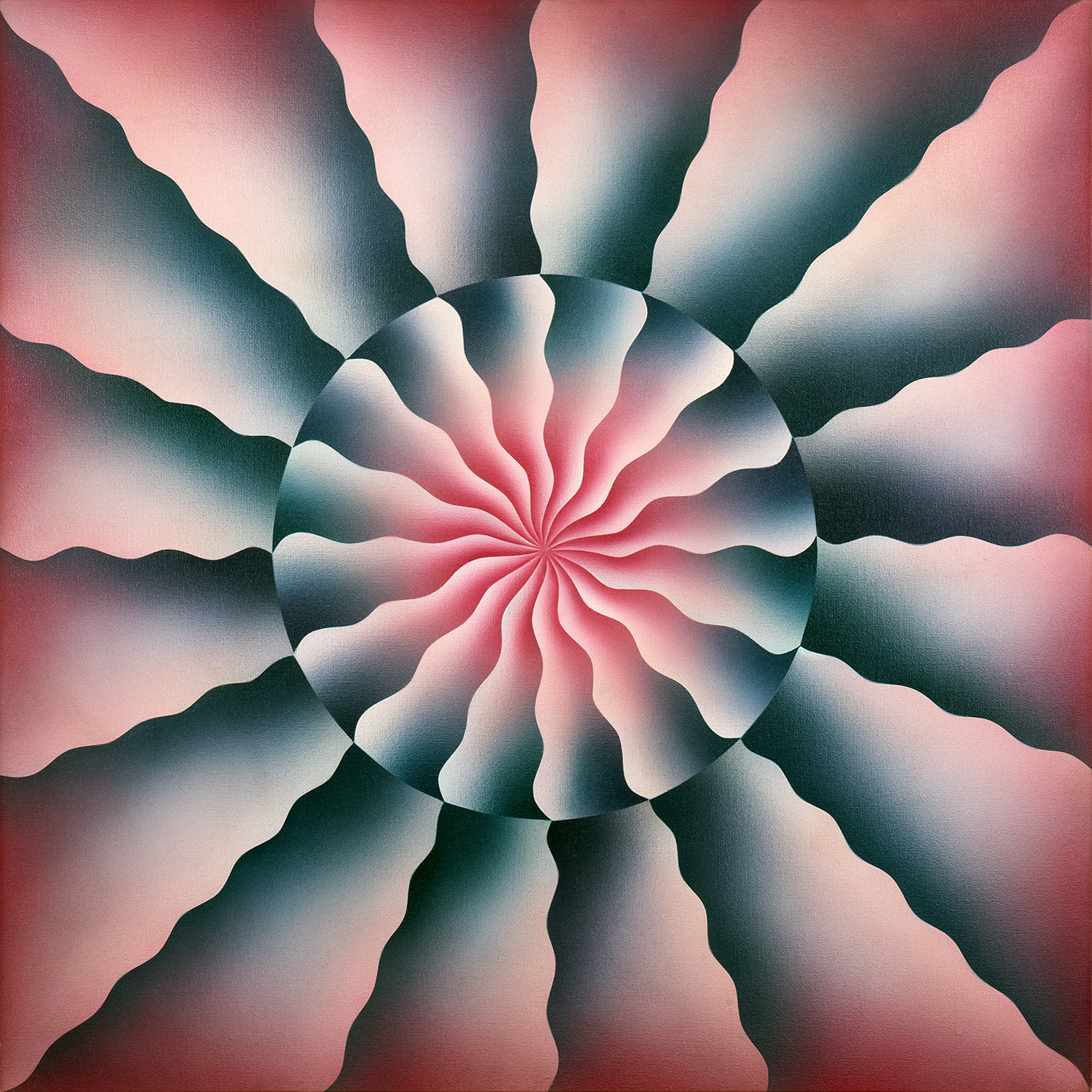

Chicago’s approach to artmaking began to crystallize in the early years of her career. After earning her master’s degree in painting and sculpture at UCLA in 1964, she found that to be taken seriously as an artist it was necessary that she adopt the modes of abstraction and Minimalism — visual languages associated with male artists. At first, she created brightly colored, highly finished Minimal sculptures such as Trinity and Sunset Squares (both 1965). Despite the critical acclaim these works received — sculptures from the same group were exhibited at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Jewish Museum in New York 2 — Chicago recalls: “I felt forced to deny parts of myself.” 3 So she soon shifted gears and began to devise an alternate visual vocabulary, a novel means by which to convey a singularly feminine experience. As she wrote in her 1973 “manifesto,” Female Imagery, “the woman artist, seeing herself as loathed, takes that very mark of her otherness and by asserting it as the hallmark of her iconography, establishes a vehicle by which to state the truth and beauty of her identity.” 4 At first, this imagery was abstract, formally organized around a center. In the painting Heaven Is for White Men Only (1973), circles of different shades of pink and yellow radiate around a luminous core, while Let It All Hang Out (1973) features thick red beams crossing over the center of the canvas at different angles, as if to block out the viewer. Playing off these transcendental motifs, the trenchant titles of the works satirize and challenge masculinity and patriarchal codes. As female subject matter grew more overt in Chicago’s work, however, her images began to gravitate closer to figuration. At the same time, Chicago sought to create an iconographic language that could be the starting point of a universal, nonphallic imagery.

Chicago’s efforts to foreground the female experience — by employing specific kinds of labor and craft and via historically marginalized subject matter and experience — was part of a broader push among feminist artists of the ’60s and ’70s. Womanhouse (1972), conceived by Chicago’s Feminist Art Program at CalArts, in Los Angeles, is exemplary here. At Womanhouse, artists executed “duration performances,” such as ironing or scrubbing the floors of the old mansion that was repurposed for the project. Installed in the house’s kitchen, Nuturant Kitchen featured fried eggs cascading down the walls and transmuting into breasts. Around the same time, in 1973–74, on the East Coast, Mierle Laderman Ukeles, a contemporary of Chicago’s, introduced the daily chores of cleaning and other domestic — and highly gendered — activities into the public realm of the museum with her “Maintenance Art” performance series. Likewise, Martha Rosler’s performance Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975) parodied television cooking demonstrations, voicing anger and frustration with the oppressive roles assigned to women. Mary Kelly’s installation Post-Partum Document (1973–79) presented a psychoanalytic account of the relationship between mother and child. Meanwhile, feminist artists in Europe such as Ulrike Rosenbach and Annegret Soltau created video works that explored the themes of pregnancy and motherhood. Much of this art challenges prevailing male narratives through the invention of autonomous modes of address. Along these lines, Chicago created a distinct female imagery in her work that represents and empowers women independently of patriarchal structures undergirding visual arts. Through her work the artist also aimed to create a community of women, in part also via her collaborative mode of production. For Birth Project, Chicago enlisted the help of more than 150 volunteers across the United States who translated the artist’s drawn and painted designs into needlework.

With Birth Project, Chicago challenges narratives of a unitary masculine God. Biblical phallocentric discourses, she has argued, generate myths that obfuscate reality: “The idea that a male god created man is such a reversal of the reality of how life comes forth,” Chicago told the New York Times in 1985. 5 If myths are a form of camouflage invented to consolidate a discourse’s power, then anything that threatens that power is denied an image. Hence, it is incumbent upon feminist artists to render female experiences and a female perspective visible, “[challenging] the age-old erasure of women’s participation in Western culture.” 6 Many of Chicago’s works, in turn, invoke mythological themes or center on the figure of the Goddess. Take, for example, The Creation (1984), an Aubusson tapestry that is one of the largest pieces in Birth Project. Connecting the process of giving birth to human evolution and various creation myths, these images, as critic Lucy Lippard has written, “merge mythical with individual content, the birth of the world and actual birth as experienced by real women.” 7 The Creation, which includes animals, organic forms, and landscapes flowing into a female figure, is “a monumental image of interconnection, fusion and emergence, full of sweeping, sensuous lines, micro and macrocosmic detail.” 8 With the large-scale Earth Birth, meanwhile, Chicago fuses landscape and a female form, revealing a more balanced merger of paint and needlework: fabric paint sprayed on black fabric and quilting, with the thread of the yarn matching the color gradient. The layers of dark fabric contrast with bright airbrushed highlights accentuating the reclining figure’s vagina, breasts, and mouth.

Such images mark an important distinction between Chicago’s approach and that of her contemporaries, particularly Pictures generation artists Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, and Sherrie Levine. (“Pictures,” an exhibition at New York’s Artist’s Space, opened three years before Chicago began Birth Project.) The Pictures artists developed a critique of representation through the appropriation of existing images. As Amelia Jones writes: “In the late 1970s and 1980s the majority of feminist artists rejected the celebration of positive images of women in favor of the explicit critique of the objectifying ‘male gaze.’” 9 Chicago, by contrast, was responding to a longer view of art history. By generating an entirely new visual language, she sought to affect a far greater structural change. As Chicago explains in an interview with Lippard in 1974, “What subject matter and what forms are important, and what the nature of art is and who defines it and who makes it, and how much it costs, are simply projections of the male value structure. If we as women challenge those values in our art, then we are challenging the whole structure of male dominance. That means you have to move outside of the structure of the art world, because you don’t get brownie points for telling men to fuck off.” 10