From Flash Art International no. 251 November–December 2006

Hans Ulrich Obrist: In a previous conversation, we spoke about moving into fields different from contemporary art. You mentioned Friedrich Kiesler. Let’s start from here.

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster: I think one reason why Kiesler is less famous than other artists is because he never wanted to be only a gallery artist. He was doing architectural work and all sorts of things, such as windows for big department stores or gallery spaces. The methods he developed have indirectly influenced many artists who don’t even recognize it. Certain artists — such as Kiesler or Isamu Noguchi when making lamps and furniture — wanted to expand the field of experiences. But art history makes it difficult for artists to escape a linear way of developing a career, and usually these artists are rediscovered much later. The art world is very conservative when it comes to behavior.

HUO: You have implemented a lot of these expanded projects: a park has happened in Kassel at Documenta 11 [Park – A Plan for Escape (2002)], another park in Grenoble, and a house in Japan [Moment Dream House (2004)].

DGF: I always look for experimental processes. I like the fact that at the beginning I don’t know how to do things and then slowly I start learning. Often exhibitions don’t give me this learning possibility anymore. With the house in Japan, I was constantly confronted with people; they were explaining to me, say, possible grids, and at each meeting I was learning something new. I like meeting with people who are very specialized in their field. I don’t find these learning moments in art enough.

HUO: I always felt that routine is the enemy of exhibitions.

DGF: Yes. There is also something very slow in the art world. People build a stage for a concert in one day; they do more in one day than they do in a gallery space in a year in terms of activity. Of course each system has it’s timing, but once you have been dealing with other speeds it is really hard to go back to this slowness.

HUO: That is the great thing about Dave Eggers’s book [You Shall Know Our Velocity], which is about knowing all the velocities. It’s impressive to see a fashion show structure being installed in a museum: it is installed at 6 am, the fashion show takes place during the day and at 6 pm it is already away, in the van!

DGF: In a museum any wall is like a white canvas, so any gesture becomes very important. I am really tired of that!

HUO: The number of such expanded field examples in your work increased exponentially. I am thinking not only of the art projects, such as the house in Japan or the parks. We are sitting in the café of the Cité de la Musique where you were involved in a sonic exhibition, “Espace Odyssée” [2004].

DGF: Yes. I am very happy to look at any proposal coming from the most varied fields, where there is a certain program, an idea, some time and a fee. It’s not that I want to be totally subjective and go my own way. On the contrary, I want to interact with all types of questions. There is nothing new in this attitude. In the 1950s, for example, there was a spreading of artists’ activities into other disciplines.

HUO: This position was also strong in the 1920s, in the Russian avant-garde.

DGF: Yes. The interaction with a diverse range of systems and structures was its radicality. There is something indulgent sometimes in the art world that I want to escape. This is why the title of Kassel park is A Plan of Escape!

HUO: When I first came to France I was asked if I wanted a plan d’evasion! It was a card for buying tickets, like national flights. There’s also a book by Henri Laborit, Éloge de la fuite…

DGF: There is something very human in “escaping.” What drives transformation is the fact that at a certain point an environment is not stimulating to you anymore. You feel you need a change; it’s a human drive to escape the too slow or too repetitive or too dead-end situations.

HUO: Recently somebody told me about the great landscape architect Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster! They didn’t know that you had an artistic background. There are other people who see your films at film festivals and talk about this young filmmaker. Suddenly you are gathering a multitude of identities.

DGF: I don’t want the films to be seen as artist’s films or the garden to be seen as an artist’s garden. I think it is important for artists to develop their role as producers or directors, which means providing a public situation for an audience — an exhibition, a theater piece or a film serve this purpose too. And for that you get a fee.

HUO: That’s what happened, for example, with your project for rock singer Alain Bashung [Gonzalez-Foerster produced the visual set for Bashung’s tour in 2003. It included two big video projections onstage].

DGF: Exactly! And it’s not parasitic. When you ask for a fee for an exhibition, they generally answer you: “Maybe you can sell this work in a gallery?” I don’t want to just sell objects, I want to work in a public environment and provide my kind of show. I have some autonomy. I haven’t done a gallery show for a long while, even if I like the galleries I work with. I gained this autonomy working in other fields. Though in a Duchampian way I have also enjoyed the “casino” aspect of the art world, like the funny lack of any rational correlation between the price of a work and the work itself. At one point I found these funny numbers, this roulette, amusing. But I don’t find it so funny anymore because when a collector buys a work for a certain price, this money comes from somewhere, it’s not abstract paper. The work made with the most critical, inventive potential often ends in a sale or in a safe or in a very depressing situation. This is why I think it is important to develop new types of work disconnected from certain formats and an artist who makes a living by doing exhibitions. Of course this system would be also open to artists who want to provide objects to that market too.

HUO: We didn’t speak about the notion of collaboration, which in your work is becoming more and more present. One thing that changed is that in the 1990s you occasionally collaborated with other artists. This has become rare in recent years; it is much less with artists and much more with other practitioners.

DGF: It’s true. Thanks to the collaboration with visual artists I learned to collaborate with artists from other fields. To me now, working with someone like Alain Bashung or Nicolas Ghesquière from Balenciaga is a way to increase this exchange. I am still happy to work with other artists, but the practice is often too similar to really learn something new.

HUO: You mentioned two collaborations, one with a musician and the other with a fashion designer. What did you learn from them?

DGF: I learned how they work in the commercial context while still being able to protect their inspiration. I wanted to prove that even if trained as a visual artist it is possible to interact with other fields! Ghesquière or Bashung metabolize lots of things dealing with so many people and details. The complexity is the ability to maintain a subjective creative process bringing into it other personalities. If you need to have one more spot of light here, this has no extra symbolic value. It’s real, without endless discussions overloaded by metaphors.

HUO: That is the reason why I started to create shows in fields where there is no security, or in places such as the Barragán House in Mexico City or in Sir John Soane’s Museum in London. It’s incredibly liberating.

DGF: I think, of course, the exhibition context is necessary as an experimental field, and even some galleries have this potential. I am against black-and-white readings.

HUO: There’s a recurrent question in my interviews: What is your unrealized project?

DGF: The thing I have been dreaming of for some years is a swimming pool on the beach. This is why I went to Brazil; I wanted to make it there. It would be a kind of “tropical university”: a place, a swimming pool, with some umbrellas to create shade. You sit in the water on the beach and discuss your ideas and projects! It has never been realized until now.

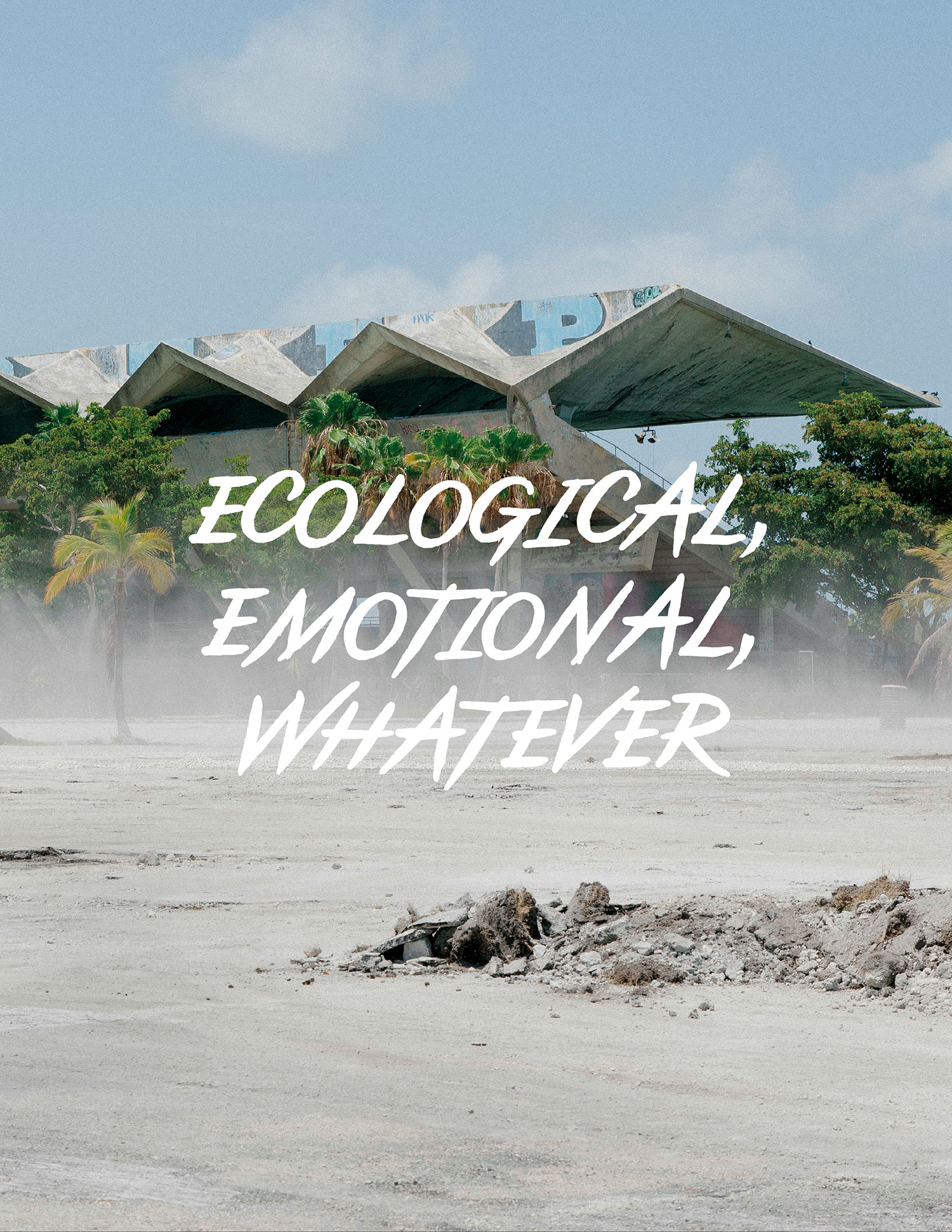

I have been going to Brazil for different reasons, such as the show “Tropicália: A Revolution in Brazilian Culture” by Carlos Basualdo, which is still traveling the world. [The exhibition was initiated by the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago; the Bronx Museum of the Arts, New York; and GabineteCultura, São Paulo.] In this exhibition he also wanted to have some contemporary artists making works after having met or visited the place, and I wanted to make this tropical university on the beach. This is a dream I had.

HUO: Another crazy seminar.

DGF: Yes, I have read the Cedric Price book you gave me and I felt I didn’t want to build anything, and I only had visions of things that are either horizontal or go deep. I don’t believe in any verticality. What I like in Rio or in Copacabana is that people are standing on the beach; they don’t sleep or they are not lying. It always looks like a giant meeting or opening and I wanted to go further with that feeling of the dynamic beach. I was so happy when he involved me in this project, because this is how I want to feel — half Japanese, half Brazilian! This is my twin entity.

HUO: Speaking of Brazil, you planned a radical assessment or re-assessment in terms of you carving out time for the whole of 2005…

DGF: Yes. My plan for 2005 was a trip around the world with no plan. A full year free, dealing with what would come up. But nothing happened as planned. There was no world tour but two long stays: in Rio de Janeiro to start the Sitio Experimental Tropical (SET) and in Paris to edit a series of films called Parc Central produced by Anna Sanders Films using video material shot all over the world in the last seven years. Parc Central is conceived like a music album and connects different urban and non-urban experiences in a similar way as I did with the CD-ROM Residence: Color (1995). In November 2005 my little girl was born… and everything changed again.

HUO: In Brazil, you wanted to build a house there. Can you tell me about Rio?

DGF: I didn’t really build a house in Brazil (that might be another step). Two years ago, I found a place, an incredible terrace in the landscape, a fantastic open-air space hidden from the street by an old house. This house needs a bit of renovation and transformation to become part of what I call the Sitio Experimental Tropical (SET), a place to experiment on the effects of tropicalization on ideas, desire and projects. Rio is an incredible city in a fantastic geological site with lots of great architecture and a “pre-individualistic” mood — the organic, fertile influence of the tropical vegetation and climate is something out of control.

HUO: What is your next project?

DGF: Writing a science fiction novel together with Philippe Parreno, keep thinking about new sorts of public spaces and playgrounds as I did for the current São Paulo Biennale, working on an “opera/exhibition” with lots of artists and friends for the Manchester International Festival, preparing a proposal for Skulptur Projekte Münster 07, and of course remaining unpredictable even for myself!