Arriving at his home in Lisbon, I am welcomed by an artwork from 1979. It is a lead panel on which three oyster shells have been mounted. In each shell, a small reservoir of oil fuels a flame that lasts just a few minutes. I immediately think of when, in 1976, Calzolari addressed an unabashedly sexual letter to his lover, simultaneously writing to Kounellis in a serious, nervous and thoughtful register regarding the condition of Italian art.

I came with a desire to speak for hours about white. How Calzolari managed to achieve that white, and what happened at the time with others who entered the spotlight thanks to the use of fluorescent tubes. I wanted to hear anecdotes about his relationship with Joseph Kosuth, Vito Acconci, or Rome, Jannis Kounellis, Taverna Palace and the International Art Meetings… To discuss what will remain of his artistic legacy. And again, to talk about the beginning, when he made drawings and sketches, before eventually creating works that, over time, began to emerge without any preparatory studies.

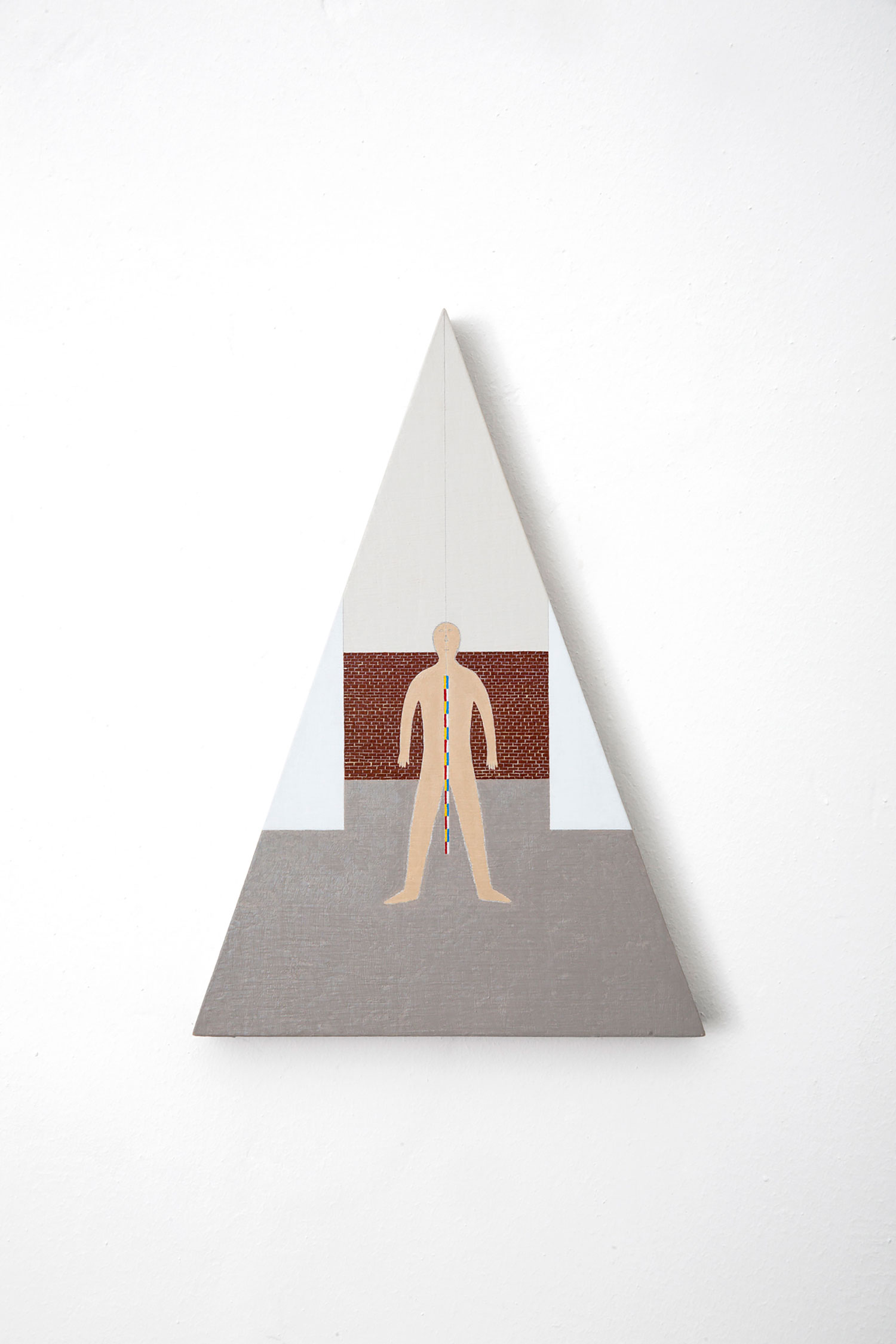

Calzolari, however, wants to talk about his new work, his show in New York at Marianne Boesky — which I visited with Kamel Mennour, a few days before our meeting in Portugal — which he summarizes as a “testament to a shift.” He wants to consider concepts like “choral prayer,” and the will to observe art history today “with a desire to bring it to life, like historical graffiti.” He whispers, “We must begin to remember art as something three-dimensional, like a hologram, where there is no past or present.”

Chiara Parisi: The shift in your work is quite obvious: first Arte Povera, then the still life series from fifteen years ago, and now a new beginning. Your practice seems to crystallize at the same time that it sheds its skin. Can you talk about these transitions?

Pier Paolo Calzolari: It has been a progressive development, not a sudden nocturnal awakening dictated by a celestial aura that made me change, or a nightmare that woke me up. The 1960s, especially but not only in Italy, were a time of great fatigue for young artists. A weariness in recognizing oneself and recognizing one’s practice. There was a terrible academic tone, a sort of mechanical repetition, an orthodoxy for making art that applied not just to figuration but to dance, theater and other forms of expression. At the time, I remember, we talked about “stray dogs” — in other words, individuals that somehow managed to “navigate within this field of research.”

In the United States some groups came of age, unlike Italy where Arte Povera never managed to establish itself as a real collective, but instead as a constellation of artists who felt a similar urgency about needing to restore meaning — by naming things, trying to revive them, giving them blood, spirit and body again.

The interesting fact is that Arte Povera never had an ideological component, and above all it has never been part of the avant-garde. In Arte Povera, the relationship between past and present was not really a relationship. The past hung there as an aspect of the hic et nunc, and the present was mixed up in this past, so it was not a problem at all to think about Giovanni Bellini and, at the same time, about a ringing telephone.

CP: You mention Bellini, and therefore also the great Italian pictorial tradition, which includes the problem of representing human figures and objects. Have you ever experienced this sense of figuration as taboo?

PPC: This question is rather about Italian criticism. Actually, some of us, not everyone, thought about how to enrich the palette through the relationship between figuration, portraiture and representation. A leaf of tobacco is figurative. It has a voice, a song and a sound. A neon sign, encased in wax, is still figurative. There is no descriptive, anthropomorphic figuration, however the idea of the figure is intensely present.

The goal, at least on my side, was to dispose of functionality, language, deliberation, figuration — these were depleted and unbearably useless. For ten, twenty years, coming of age, I found this to be annoying and suffocating. An art that, for both talented and not-so-talented artists, presents itself, even in the best cases, as a form of repetition. Repetition of itself, repetition of other things. I do not consider it a crime; an artist can do what he wants. Rather, I find it atrocious to hear about and pay attention to these “products” because they lead to boredom and unhappiness, which in turn fosters the discovery of an arid island, a loss of the primary traits that motivate an artist — that is, curiosity and the thrill of discovery.

CP: There are many artists who always see something different in repetition. Some made it their style, experiencing the repetition of an artistic gesture as a “mantra,” or else dwelling on details and seemingly marginal subjects.

PPC: Of course, there are some cases: Morandi, for example. But we know that we are talking about style; it’s clear that both in the United States and in Europe we have witnessed a reiteration of these repetitive styles which, except in a very few cases, have lead to boredom and almost a desire to renounce the act of creation. Talking repeatedly about the known is useless and boring. For my part I tried to reset. What happened in postwar Japan, the year zero, the tabula rasa, were lessons for me.

CP: “Tabula rasa” suggests an idea of resetting as well as a sense of humility that is almost a spiritual connection.

PPC: The great philosophical lesson of Francis of Assisi, which unfortunately was reinterpreted and killed at the ecclesiastical level, was so important for me. His layman’s thinking conceptually brought forth the Copernican Revolution: “Sister Water, Brother Fire.”

He was the first man, after some Greek thinkers, able to overturn our anthropomorphic vision in terms of reading the world: listening to water, birds, a dialogue with the other… Conversing with things, taking them as living entities.

CP: Let’s get back to making art. Yesterday and today, do you see things differently? Did the return to painting mean losing that strong sensual charge? How does your New York show compare to exhibitions from the late 1960s and early 1970s — most especially “Avere pallido il viso, avere bianco il viso” (To have a pale face, to have a white face) at Lucrezia De Domizio Gallery in Pescara (Italy, 1975)?

PPC: In the 1960s reality was different, totalizing, dictatorial. There was a sort of aristocracy of art, not a democratic “dissemination” of it, which instead I observe now. There was a rage of revolt; we were all angry about the repetitive nature of things. Now there is no excuse for rage. There is a totalization in the banalization of style, the commonplace, quotations, quotations of quotations, such that there is no more anger, only boredom.

CP: However, it seems as if your desire to work has not changed, not since 1965. You’ve always been productive.

PPC: At one time it was a compulsion, a scream, a syncope; I think, for me, as with some other artists, they were sharp and meaningful screams. Today, I confront things by thinking of language and its internal logic, yet with the humility to be fascinated by a tapestry, to try to see its microscopic details.

CP: Talking about detail… Seeing the way you look at the photos of your show at Marianne Boesky, it seems like you’re amazed by details. It’s as if your works were themselves huge details, real-life clues on a scale they seem not to belong to.

PPC: Details are a time for prayer, a choral prayer. I have come to see the act of making as an act of prayer. It sounds a bit absurd, as I don’t know exactly what I’m praying for. It’s an act of prayer toward oneself, repeating, watching. Think of paintings in Cretan corridors, or of ancient African graffiti, Japanese shields, and see them as a vibration, confront them, understand them for what they really are. Understand how to feel lost in a rug. These are lessons given by Monet and some American artists. Jasper Johns’s flags and Monet’s lakes were a pretext for painting…

CP: In many of your works everything seems to lead toward white: the ice, the light and their transformative power. We have not talked yet about the neon you frequently employ.

PPC: I used a very thin neon, 0.5 or 0.6, called capillare (capillary); I use it so you can barely perceive it, as if it were a shimmer, employing it normally for small gestures, small signs or to make sentences.

The use of fluorescent tubes allows a maximum saturation of light and color. Think of Dan Flavin, who used them as a pictorial palette. He made extraordinary shades with fluorescent colors, typical of Klee, and John Baldessari, whose work demonstrated a great culture of color and complementarity. I feel different from them, in spite of my great admiration. For me neon has always been a spoken poem; I never used it as an icon as such. It has been a very smooth presence with the least possible internal light, like a murmur.

CP: On the occasion of your last show in New York, you’ve been inspired by art history, from Japanese decorative art to what remains of the Greek and Pompean epoch. Of figuration and representation there seems to be no trace. Combining such disparate historical styles and moments is not a simple venture. Are you satisfied with what you did?

PPC: Absolute black, white, salt, spatial interventions: if you think about it, they resurface with physical strength. I was fascinated by Mannerist and Baroque landscapes. From Rosso Fiorentino to El Greco, the Mannerist landscape is violent, expressive, full of passion. With Tintoretto and his nocturnal studies a few decades later, landscapes loaded with pathos changed with the arrival of the Baroque. They became inexpressive and mute, as if they were motivated by pure representation and not any meaningful elements. In this exhibition, I look at art history with a desire to revisit historical graffiti. If you do not confine them to an art history book, past artworks appear three-dimensional and are tremendously engaging; they must be remodeled, rediscovered, relived to understand their meaning. This is true for some works in the series “Piombi” (leads) in this last exhibition, which are oriental landscapes with oxidation and small recurring motifs such as peacocks. There is also the use of decorative art, evoked by sewn and suspended threads.

CP: In your personal and professional life: any regrets, desires or dreams still to be realized? Any ghosts perhaps?

PPC: I removed them through my practice. I experience them at night maybe, not in my work. One day, maybe, they will come out. From time to time.

CP: Do you think that when this awareness emerges, an artist should destroy what he did? Some have.

PPC: Sometimes I destroy my work with a lot of effort and courage, even old works. I have always destroyed artworks that became sort of manneristic. I need air and sensuality. Allen Ginsberg’s Howl (1956) is beautiful because it is a statement of just this fact — an impotent state, a disobedient and affectionate shout generated by the absence of oxygen. When you start to have oxygen you can’t continue screaming.

CP: Could you destroy the New York show? On the other hand, the artist lives on reflections and feelings of inadequacy; is there something you don’t like in the show, even though it has not been up for very long?

PPC: No, because it is a testament to the moment. In that precise moment I can see defects and failures, I can experience anxiety and be curious to look at something. There may be good and not-so-good works, but they are innocent exhibitions; they have the virtue of curiosity.

CP: Do you think is it still possible to be innocent?

PPC: Things exist because there are real and primary reasons for making them alive. When I talk about the scream, it can’t be reduced to language. It is a syncope; beyond that moment everything is frightening, nothing makes sense.

CP: The titles of your exhibitions raise many questions. Do you want to be remembered as a poet?

PPC: I try to be clear and not provocative. The questions posed by titles are often without answers. Rather, they involve a questioning dialogue with the world: “When the dreamer dies, what happens to the dream?” It’s a question without an immediate response, but a question that demands reflection.

CP: Do you consider yourself cynical? Is there a work in particular that you consider “cruel”?

PPC: None of mine. But there are other authors I consider “cruel.” The most cruel artwork, in my opinion, is Goya’s El Perro (1819), with a dog’s head emerging.

To be cruel means having an interlocutor, both physical and theoretical, which is the world. I don’t have this. I live a lot in memory or according to what I see. There is no interlocutor in my idea of my work. I don’t know him or her. Some artists, it is obvious, have a ghost or a theoretical interlocutor.

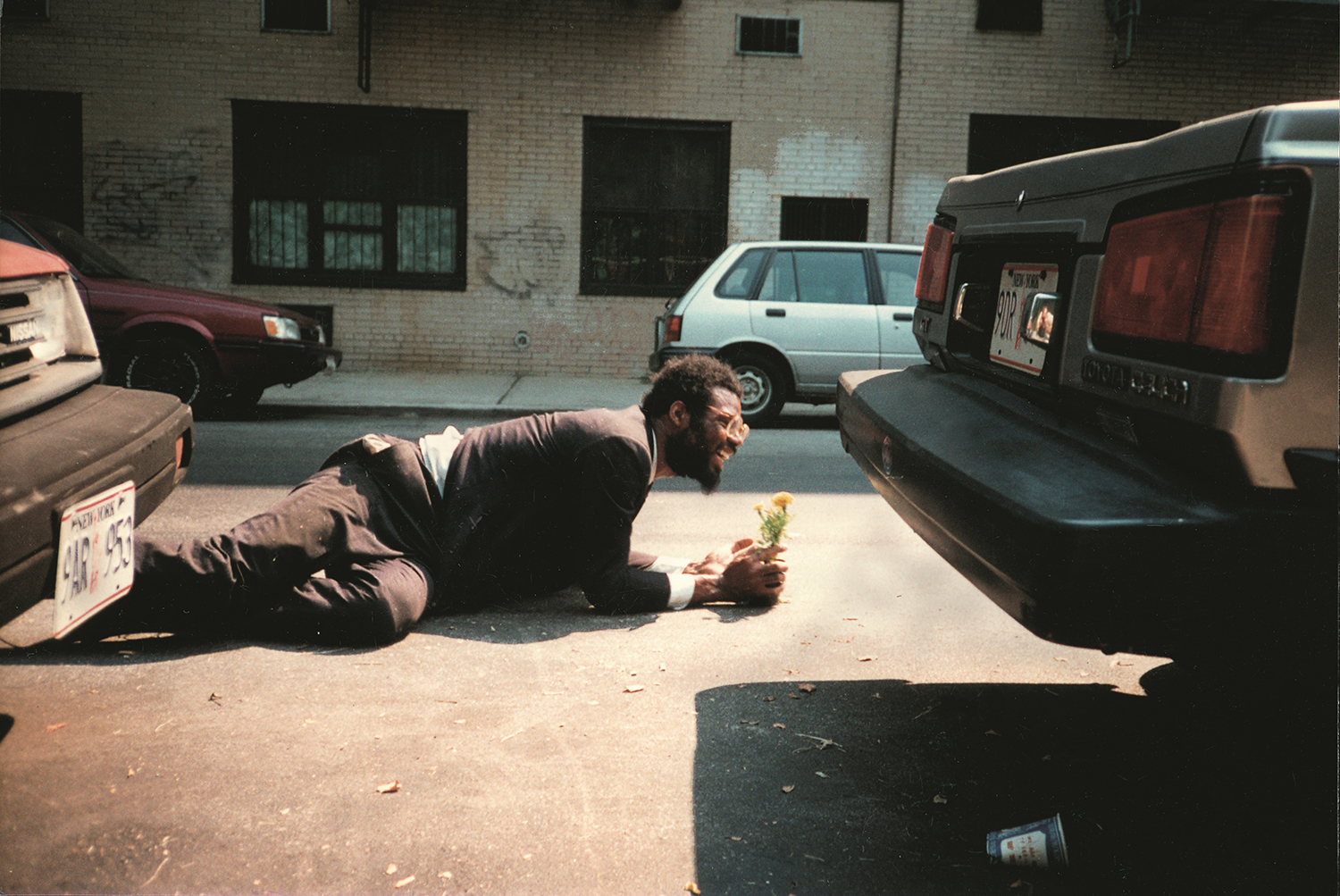

CP: When you create a performance, is the presence of a living figure something that interests you, or is it just a pretext for something else? The latest exhibition at Kamel Mennour featured a series of videos documenting performances made over many years. In these works, full of human presences, many of which are feminine, you do not appear much. These are situations always characterized by great discipline. At that time many artists made performances. Chris Burden and Paul McCarthy, just to name two examples. Why should your performances be remembered?

PPC: With respect to performance, my thoughts approach the idea of the “great party” that was already taught by Leonardo da Vinci, the sumptuous setups for animated games of water and fire, mechanical robots, animals… In performance, I see a deletion of the context of the sublime, of the other, a light touch that can be seen as Pan’s veil, protecting us from reality, hiding it. Sometimes we break it down and see true reality, and that means panic. We discover the macabre, the totality. The sublime always concerns this realm. They are often memories, mythological indications of femininity, abstract images compared to the physicality of a person in flesh and bones.

CP: I seem to remember a performance with Emilio Prini… I know that at some point you spent time together.

PPC: We were among the few not from Turin, though we were part of the feudo speroniano (Gian Enzo Sperone’s feud). We came from different cultures, like Alighiero [Boetti], and with less daily promiscuity we brought different things. Despite this, we were appreciated and respected by others. Emilio had a destructive will, but we shared several things.

In Genoa we made a performance by swapping our clothes. It was a grotesque and nice performance at his home. He was plump, and taller than me. My clothes looked very tight on him and his looked very ample on me. He put on a potato nose. We usually worked on the dislocation of personality. We had to make two sculptures — his made of frost, mine of tar — a project among many others, unrealized, because he was parsimonious, and I didn’t have much money.

CP: Returning to cruelty… Do you ask your viewers to have as much patience as you seem to have?

PPC: In Scala (con Piuma) (Ladder [with feather]) from the 1970s there are faint sounds that make feathers vibrate slightly. I was looking at Zen culture a lot in that moment; it’s not my problem if no one notices. If you’re attentive to the feathers you can see each one moving differently, because each one has a different sound.

CP: Aren’t you still asking for this kind of attentiveness?

PPC: The ancient Greeks knew that your specific weight changes depending on whether you approach a tree or a stone. We have just forgotten, and it is interesting to rediscover this, just as a feather is moved by wind or other types of vibrations. Or, find a way in 2016 to make flowers with pins. If you love the details, you will realize they are pins.

CP: I confess, I also feel a bit like a feather in the wind listening to you. You have cited past epochs, artistic languages separated from each other not only by time but also geography.

PPC: I think that art history can be imagined as an African graffiti with its three-dimensional power. We must begin to remember art as three-dimensional, like a hologram where there is no past or present. That is, for me, the New York show.