From Flash Art International no. 123,1985

Michael Kohn: How about starting with a serious question: Your work has been called neo-surrealist. What does this mean to you?

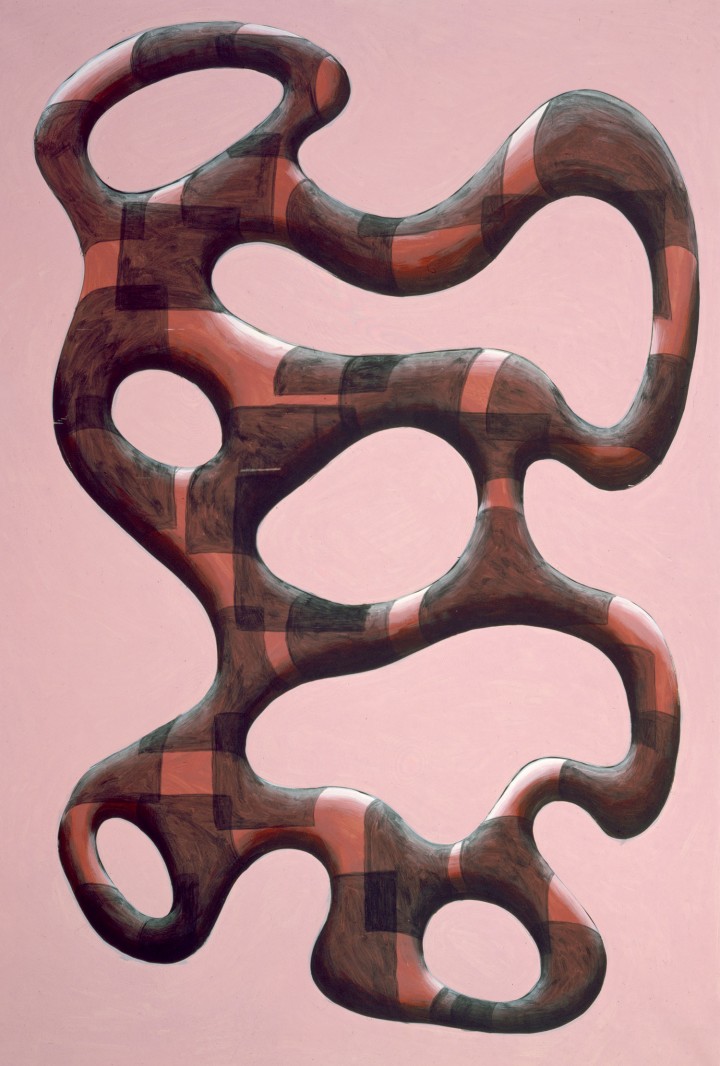

Peter Schuyff: There are surface things in Surrealism that interest me. Things that make my paintings look like Surrealism, but they aren’t Surrealism. There is none of the mysticism, none of the deadening of reality. There are some purely visual, purely painterly things that make it look on the surface like Surrealism. On the surface it looks like Tanguy has influenced me, on the surface it looks like Léger has influenced me. But they’re really just surface things.

MK: So they just happen to look alike. Like the review that talked about biomorphic shapes last year.

PS: Yes. Some people seem to think so. The work at that time was a little different. It is as if the work was one character in a play that now has four characters. But at that time I was painting these shapes, doilies on a background. And now a few other things are going on simultaneously.

MK: By the same token, your work has been referred to as formulaic, which means that the work doesn’t go anywhere after a certain point.

PS: I could almost agree with that, but I wouldn’t see it as pejorative. Rather than repeating itself, the work is simply exploring further. You have to keep up with the work to see: not how the formula is broken — because that would be a crime — but how it has been bent and twisted to the point where there is sufficient stuff to make paintings. I am still painting with the same brushes, and my work is still about the same ideas.

MK: Your work is not narrative. Does that mean that it is basically abstract?

PS: No, not really. A woman telephoned me and asked me, “What are your paintings about?” And I said, “Don’t worry about that now. Just be thankful they are there.” I thought about that afterwards, and that really describes to me how my paintings are about nothing. How they deal with the problem of nothing.

MK: Can you talk about your work in terms of an evolution, from when it appeared in the International Transavangarde until now?

PS: There were a lot of drips, a lot of action, and a lot of toning. The idea at that time was very much the “yes-no” of picture painting. But they were pictures, and, as you say, illusionistic in a way. They had light and shadow. They were traditional still lifes, and in fact it was a set of art-student geometry shapes where you could set up cones and spheres. The early paintings were a nice little potpourri of sculpture, painting and literature because in the background there was writing, poems. Usually there were just one or two words, or sometimes no words and just characters. But again, the newsprint, the poster paint, the drips… and they were painted very fast — they were by no means realistic. And because of some quick wrist action, the light and shadow were there to their fullest. And that is a relationship that I am definitely still interested in.

MK: What other artists are you interested in?

PS: Tanguy, before. Now I am thinking a lot about Fontana and what makes his paintings look really exciting. They weren’t so interesting six or seven years ago. The same is true of Jean Cocteau and Tapiés. Now, all of a sudden, they look interesting. It is stylistic to me. It is taste.

MK: What other types of influences have affected you? You once said to me that Pollock’s drawings influenced you very much, but there is a vast difference between the free-flowing surrealism of early Pollock and the controlled tightness of your paintings.

PS: Compositionally there are a lot of similarities.

I have learned a great deal about the composition of my paintings by looking at Pollock. For me, the composition exists by looking at the outer edges of the canvas, and yet I rarely go off the edges. And my paintings are not so tightly controlled, although they appear so, and I like them to look that way. I think a lot of the pleasure of looking at a great painting has to do with an empathy for the wrist action. I get a great kick out of seeing a game of pool played really beautifully. And it is the same with a painting. I like to see that there is a facility, and the empathy for that facility is one of the most enjoyable things of looking at a great painting. I am an aesthete.

MK: This is one of the great differences between the artists of today and those of ten years ago, the minimalists and conceptualists. They would not have said, “I love doing it because it looks fabulous on the wall.”

PS: But still not one of them has gotten away with doing anything shabby. And there are a million different kinds of wrist action. You can’t tell me that you go up to one of Schnabel’s paintings and you don’t empathize with his wrist action, of which he has an incredible amount. This guy can push it around like no one else. And when you look at one of his paintings, that is so much of what you are getting. As a painter that is the way I see it. I have been inspired by other paintings, and that is where I get a lot of my information. And to a certain degree I am naive when I look at paintings, because most of the paintings that have become really important to me have done so for fairly superficial reasons. What inspires me is not what is in my paintings. I think the painter’s role is not to be inspired, and Van Gogh was inspired to the point where it could almost cause him real problems. The role of the painting is to inspire, not to be a relic of inspiration. When you look at such a relic it can be really annoying. I either feel it is none of my business, or I feel that the painter has a lot of nerve for throwing all this stuff down my throat. The role of a painting is to inspire.

MK: Well, sometimes a painting does both. It can be a clue to a painter’s own problems, but at the same time It can send out its own signals. That makes a painting heavier, more concentrated and intense. You said you liked Monet, but Monet offers simply what is on the canvas, in a sense.

PS: But what is on the canvas for Monet is very profound. When I look at those paintings I can tell that somebody has deliberately made them. It was a very premeditated, conscious gesture. Monet’s paintings inspire me, and Van Gogh’s paintings tell me how inspired Van Gogh was. And for that reason I much prefer Monet. But if I have to tell what my paintings are about, they are really about physics, about quantum mechanics and a lot of these ideas. Just as Yves Klein was interested in mysticism, in an almost identical way my paintings are illustrations of physics, but not the kind you find in a textbook. It is the study of subatomic particles. But, of course, if I knew all about physics, I don’t know if I would paint this way. I am reading about it, but it is not a conscious thing, I don’t take this information to the studio and paint it. But after the last couple of months and looking at these paintings I am seeing connection there. And for once it is not a visual, painterly connection. The paintings don’t look like diagrams and illustrations in Scientific American.

MK: It sounds to me, in essence, that what you are saying is that when an artist does something remarkably beautiful, that is what hits it for you.

PS: No, it is when a painter does something and it is successful not coincidentally. lf somebody who is completely out of their mind is given a couple of tubes of paint and a piece of paper, maybe they come up with something interesting, right? But that doesn’t interest me. I need qualifications, and for God’s sake, by qualifications I don’t mean that somebody can draw or render. It doesn’t have anything to do with that. It has to do with motives and incentives, a control and a studiousness. I have real faith in what a painting does, aside from its narrative intentions. I have real faith in not having to enforce its meaning verbally. And out of my recent paintings, they quite often exist decoratively. Goya’s paintings are decorative; they are also extremely profound. Again, for him it is like an extroverted act. At first glance you don’t see this tormented human being that was so moved by the events around him that he had to make these paintings. He simply made objects that were strong, profound, meaningful — they’re beautiful. But I cannot find Van Gogh’s paintings beautiful, for the reason that the man was inspired to the point that he wasn’t in control.

MK: A lot of great works of art share similar characteristics. There is no reason that a Fontana couldn’t sit on the wall next to a mannerist painting and you couldn’t love them both, for entirely different reasons. There is a whole set of emphases that are different in each work, and it seems to me that your emphasis is on notions of beauty and elegance. There is a great elegance to Fontana’s torn canvases.

PS: Of course, and it is not something that he was not aware of. That comes closer to what my point is. I think beauty may be a misleading word that needs to be qualified. But when you see my show, I think you’ll be able to successfully ask me, in your language, what these paintings are about.