An interview with Massimiliano Gioni by Silvia Conta

SILVIA CONTA: “Ostalgia” is the title of the show you have curated for the New Museum in New York, of which you are also Associate Director. The exhibition unfolds through some hundred artworks by over 50 international artists of very different ages — born between the late 1800s and the ’80s — from about 20 countries. What does “ostalgia” mean, exactly? Is it a nostalgia for something real, or a form of melancholy that stems from losing a mythicized aspect of history?

Massimiliano Gioni: The title “Ostalgia” refers to the German word Ostalgie, which came into usage in the early ’90s. Since it derives from “Ost” — meaning “east” — and “Nostalgie” — meaning “nostalgia” — it means “nostalgia for the East.” This term was coined to express the sense of disorientation and trauma that people felt in East Germany after the fall of the Berlin Wall. In Western Europe this phenomenon came into popular awareness, perhaps in a trivialized form, primarily through movies like Good Bye Lenin! (2003) and The Lives of Others (2006). Neologisms tend to arise in conjunction with a shift so radical that people need new terms to describe an entire new range of emotions. Over 20 years have passed since the dissolution of the Soviet bloc, the end of the Warsaw Pact and the unification of Germany; I wanted to take a look back at what took place in the emotional landscape shaped by those events, which may soon vanish completely. The countries that were involved experienced a sudden acceleration combined with a yearning to identify themselves with Europe; no sooner did they break away from the Soviet Union than they began claiming a place within the European Union. In this kind of acceleration, it is easy for a chapter in history to be buried, forgotten, even rejected. Though of course, this is not an exhibition that celebrates totalitarian regimes, I should make that clear.

SC: How did the idea for the show come about?

MG: It was in gestation for quite a while, even though, from a practical point of view, the execution was very fast. The exhibition is the result of research I’ve been doing since around 2000, but I started working properly on the show only in 2010. “Ostalgia” essentially took off from two starting points: one was the Phil Collins’ film marxism today (Prologue) (2010), in which the artist interviews people who experienced the trauma of German reunification first-hand, and the other was the figure of Andrei Monastyrski, a consummate example of the kind of artist who was invisible to the Soviet official system, who took on a key moral and ethical role precisely because of this underground status. “Ostalgia” is also deeply rooted in the history of the New Museum, which in 1986 became the first museum in the US to organize an exhibition on Sots Art, curated by Margarita Tupitsyn. Moreover, there hasn’t yet been a major show in the US about Eastern European art after the Berlin Wall, save perhaps “Beyond Belief” at the MCA Chicago in 1995 or, more recently, “Art of Two Germanys/Cold War Cultures” at LACMA (2009), whereas in Europe, the subject has been explored in greater depth. “Ostalgia” was also very much influenced by the fact that early on I was working at Flash Art, which played a pioneering role in providing information about the work of artists behind the Iron curtain. And a fundamental role was also played by the Victoria Foundation in Moscow, which supported the exhibition and worked with me to facilitate the research on the ground in Russia and beyond.

SC: In your essay for the exhibition catalog, you describe this show as “an exercise in translation, interpretation, and negotiation between distant cultures,” thus revealing that one focal point of the show is the complexity and vibrancy of the present.

MG: At this point it is clearly impossible to make an exhibition that tells the story of the entire Soviet Bloc. So the show can’t be systematic, nor does it aspire to be so in any way. I’ve chosen an approach that is neither geographic nor chronological, trying instead to capture a cultural climate and a particular psychological and anthropological dimension, as well as the relationship between different generations who lived under communism or who know about it only second-hand, through their parents. It’s a show about a state of mind, perhaps; an emotional landscape. In this sense, one major influence was the exhibition “The Promises of the Past” (2010) at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and two aspects of it in particular: the way it approached the subject through a non-linear narrative, and the fact that several Western artists were included as a counterpoint to the Eastern ones. Rather than presenting a single, official version of history, I was especially interested in rendering the idea that history is made up of many different individual memories. I think that a show about such a delicate topic can’t be impressionistic. It should strive to be as complete as possible, but stop short whenever it begins to take on the tone of official historiography, because in these Eastern countries, more than anywhere else, history is constantly being revised and rewritten.

SC: How did you pick the artists for the show? I noticed the exhibition includes works by artists one might call outsiders.

MG: First of all, I wanted to show people who were not very well-known in America. So I intentionally left out some major figures like Marina Abramović or Ilya Kabakov; their importance remains in the background, suggested by their very absence. I left them out because I didn’t want “Ostalgia” to come across as a canon of Eastern European art. I wanted it to be more personal — an individual story that is fickle and subjective, just like memory, which is the underlying theme. That’s one reason why I chose marginal or isolated figures like Alexander Pavlovich Lobanov — an artist that used to draw self-portraits and portraits of Lenin and Stalin while in a mental hospital or, say, Evgenij Kozlov, who created an extraordinary erotic album when he was only 14 years old. In some sense, “Ostalgia” is like a historical novel in which some of the characters are well-known figures while others are obscure ones that I think ought to be rediscovered. This has been a hallmark of my recent shows, which mix together insiders and outsiders, for lack of a better definition. The concept becomes even more important when dealing with the Soviet Union and other communist countries, because all artists were basically outsiders, they all lacked official recognition and worked outside of the system. It was this very exclusion that made an artist a prophet and a voice of dissent; paradoxically, it was through isolation that an artist would become more important.

SC: How did you structure the exhibition?

MG: The show is organized like a vast archive, or a big ethnographic exhibit. Despite my emphasis on individual stories, I wanted the structure of the show to evoke the sometimes repetitive, taxonomical approach you expect to find in archives or in certain museums. The constant clash between the personal voices and this rigid construction perhaps represents the contrast between the individual and the collectivity that was a pivotal part of life in Soviet socialist countries. In this sense, I wanted the show to reflect the ongoing friction that existed between the polyphony of individuals and the general structure of society. I also wanted to highlight the generational aspect: some of the artists are elderly, some extremely young, but all of them must find ways to describe the past and the present, to hand it down to future generations. In the end, the main character in this historical novel, the unifying factor in the show, is paradoxically absent, since it’s the Communist regime or system which has now dissolved. Memories; memoirs and tales are all that’s left. So it’s no coincidence that one recurring element in the show is the concept of myth and fiction. On the one hand, there’s the myth constructed by the Communist Party and the artists’ reaction to it; on the other, there’s the myth of the past that younger artists are now reconstructing or inventing. And then there’s the myth of the enemy that was constructed by the West. Throughout the exhibition, we find the recurring figure of the artist-as-archeologist, digging up the past, and the artist-as-novelist, simply inventing it out of fragments of reality, recollections, or his or her imagination.

SC: In your catalog essay you mention the fact that these countries lacked a real art market, and how this influenced the role of artists, the way they worked, and how they chose to disseminate their art.

MG: The first generation of conceptual artists in the Soviet Union (such as Andrei Monastyrski, Viktor Pivovarov, Kabakov, etc.) witnessed a profound anthropological transformation, and their ethical stance in regard to it is one of the linchpins of the show. Boris Groys has written profusely on this subject: according to him, an artist working in a communist system is outside of the market and outside of any kind of system, and this ostracism makes him morally invincible. Groys highlights a fundamental concept: if an artist’s work has become important enough to attract the attention of KGB or the Stasi, it means that what that person is doing is of immense ethical significance. So the lack of an art market paradoxically makes artists more powerful, even though this power may only touch the lives of a few dozen people, within a viewing community of “true believers.” This concept was bolstered by the fact that secrecy had to be maintained, and the smaller the circle of people who came into contact with the work, the greater its expressive power. The idea of an artwork as a secret and a revelation was therefore a pivotal aesthetic notion for all the artists working underground: Monastyrski, Jiří Kovanda, Helga Paris or Hermann Glöckner, for instance. And I think that nowadays, this is a very significant idea for artists like Tino Sehgal or Kai Althoff, who are dealing with a completely different system. I was very interested in highlighting this aspect — polemically — in a period when Western economies are going through a recession, and to bring it up precisely in the city of New York, where one can most clearly see how artists gain recognition through economic success, by making money, and by speaking to an audience as big as the audience for a movie or a commercial. I wanted to put together a show that would remind us that art can be made out of nothing, and without a market; many of the works in the show consist in actions, often invisible ones, like hanging up a banner on the outskirts of Moscow.

SC: You’ve chosen to focus on conceptual art in particular; why is that?

MG: I wanted to emphasize the polyphony of conceptual art, to explore it as a global phenomenon that is not limited to artists like Vito Acconci or Bruce Nauman. For instance, Mladen Stilinović is an interesting figure. He began working as a conceptual artist in the former Yugoslavia around the same period that Acconci, Art & Language, etc. were getting underway. Stilinović wrote a manifesto — which is republished in the catalog — arguing that true artists cannot exist in the West because they are too distracted by the market; true artists reside in the East because artists must be lazy, and that’s the only place where they can do that. Stilinović made many artworks on the subject of laziness, on the idea of resting. There seems to be a cult of “Oblomov” — the central character of Ivan Goncharov’s homonymous novel from 1859 — in the East: a focus on doing nothing, or doing very little, which is another recurrent theme in the show. Paradoxically, actions of this kind could become a form of resistance in contemporary Western cultures as well, perhaps even in some part of Asia. After all, the last rule that an artist can break nowadays is to refuse to be productive, cultivating some way of wasting energy, which is perhaps the last way to reject capitalism. I don’t want to sound too Manichean, but I think this is a very pressing matter in today’s cultural environment: how can an artist avoid being an accomplice of the system while working within it? Some art from the East foreshadowed this refusal to produce work, although in those countries this attitude takes on even more complex existential nuances.

SC: There are quite a few photographs and videos in the show. What do you think is the relationship between art and documentary?

MG: Milan Kundera says that the power struggle of the ’80s in Eastern Europe was a struggle against amnesia, so in many Soviet Bloc countries, the process of gaining access to documentary tools and to the media was a process of conquest and emancipation. On the one hand, there was an attempt to draw heavily on current events while, on the other, the digital revolution was underway, even in the West. Camcorders and VCRs became more and more readily available in the ’80s and ’90s, allowing artists to tell stories first-hand. In Eastern countries, artists felt the need to also be reporters, becoming directly involved in the narration of history which, up to that point, had been the exclusive domain of official media and propaganda. Many of the works in the show use analog technology. In a way, this is a pre-digital show, presenting memories that have been constructed with methods of reproduction that are themselves beginning to vanish, much like the world they portray.

SC: Running parallel to these ideas are the recurring themes of language and the body, which seem particularly significant in this context. Why is that?

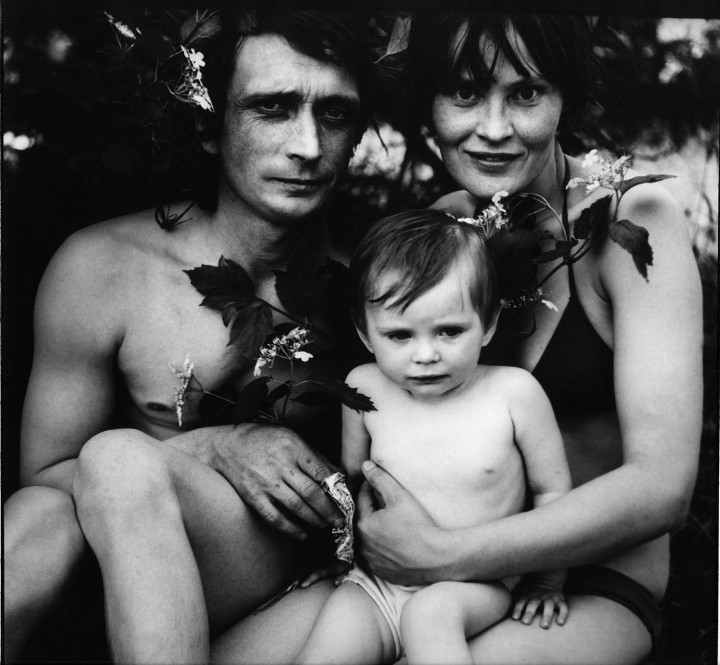

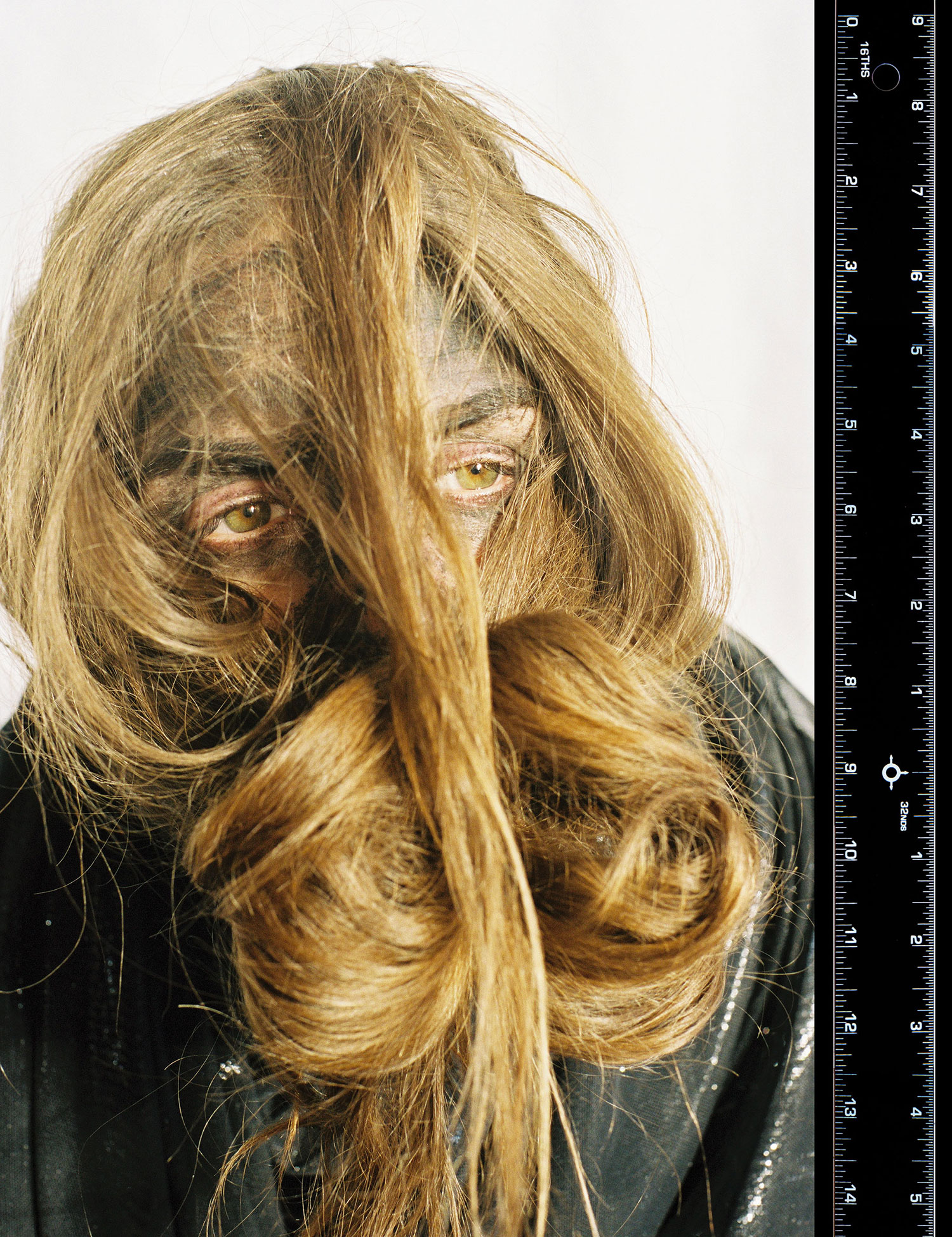

MG: The question of language is closely tied to the idea of memory and rediscovery; language is never innocent or neutral. In many of these nations, everyday language was deformed, reshaped by the language of propaganda and bureaucracy, and artists reacted to this by smashing language to pieces, putting the fragments back together, analyzing it, disassembling it, as in the work of Dmitri Prigov, Pivovarov, Stilinović and again, Monastyrski. Parallel to this is the language of the body: corporeality has often been a key theme in the history of Eastern European art. A few years back, the Museum of Modern Art Ljubljana had a show called “Body and the East” (1998) that investigated how Eastern European artists had created a more expressive, more violent kind of body art. This was probably in reaction to a lifestyle and regime in which the body was presented as a pure, perfect object — the heroic bodies of the victorious proletarians that you see in posters. Many artists reacted to this by portraying suffering bodies, as Boris Mikhailov did, or narrating erotic fantasies taken to a fever pitch, as Kozlov did. There’s one other point we shouldn’t overlook: the fall of communism was followed by interethnic violence — just think of the former Yugoslavia and the many wars in the southern part of the former USSR — and thus an extremely dramatic, violent physicality. In the exhibition, this can be seen in the works of Jasmila Zbanic, Anri Sala, David Ter-Oganyan and Andra Ursuta.

SC: This isn’t actually a nostalgic show. But if there were any nostalgia involved, what would it be for?

MG: I think that the only true nostalgia is for a time in history when an artist could exist outside the market, and play a pivotal role in art and culture precisely because of this. This idea goes hand in hand with the theme of artistic responsibility, of the artist as a witness and a prophet, someone who can change the world even through simple, secret actions. Maybe this is really just my own nostalgia; maybe it’s just a myth. But if millions of people once survived on myths in a realm as vast as the former Soviet Bloc, then why shouldn’t we do the same?