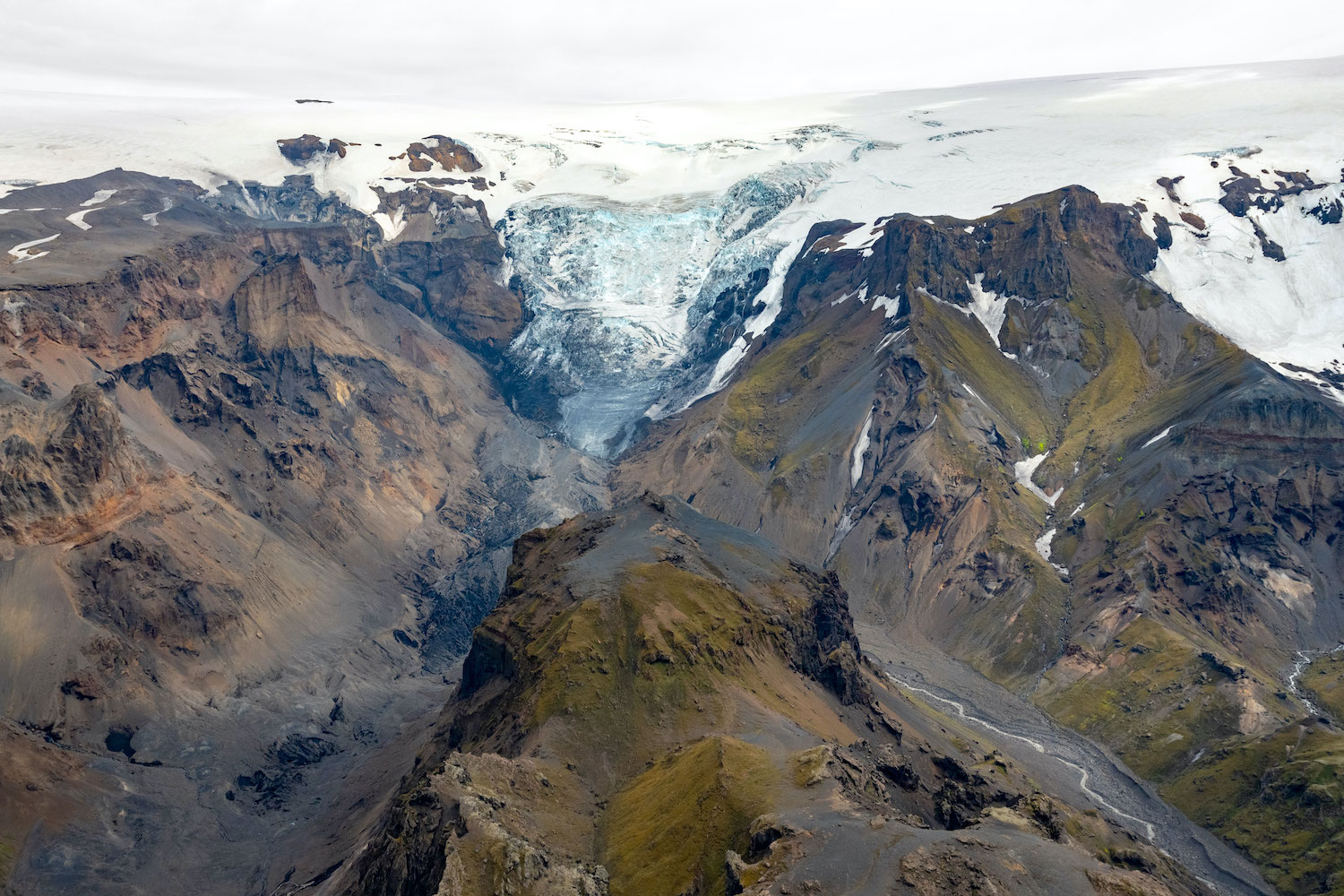

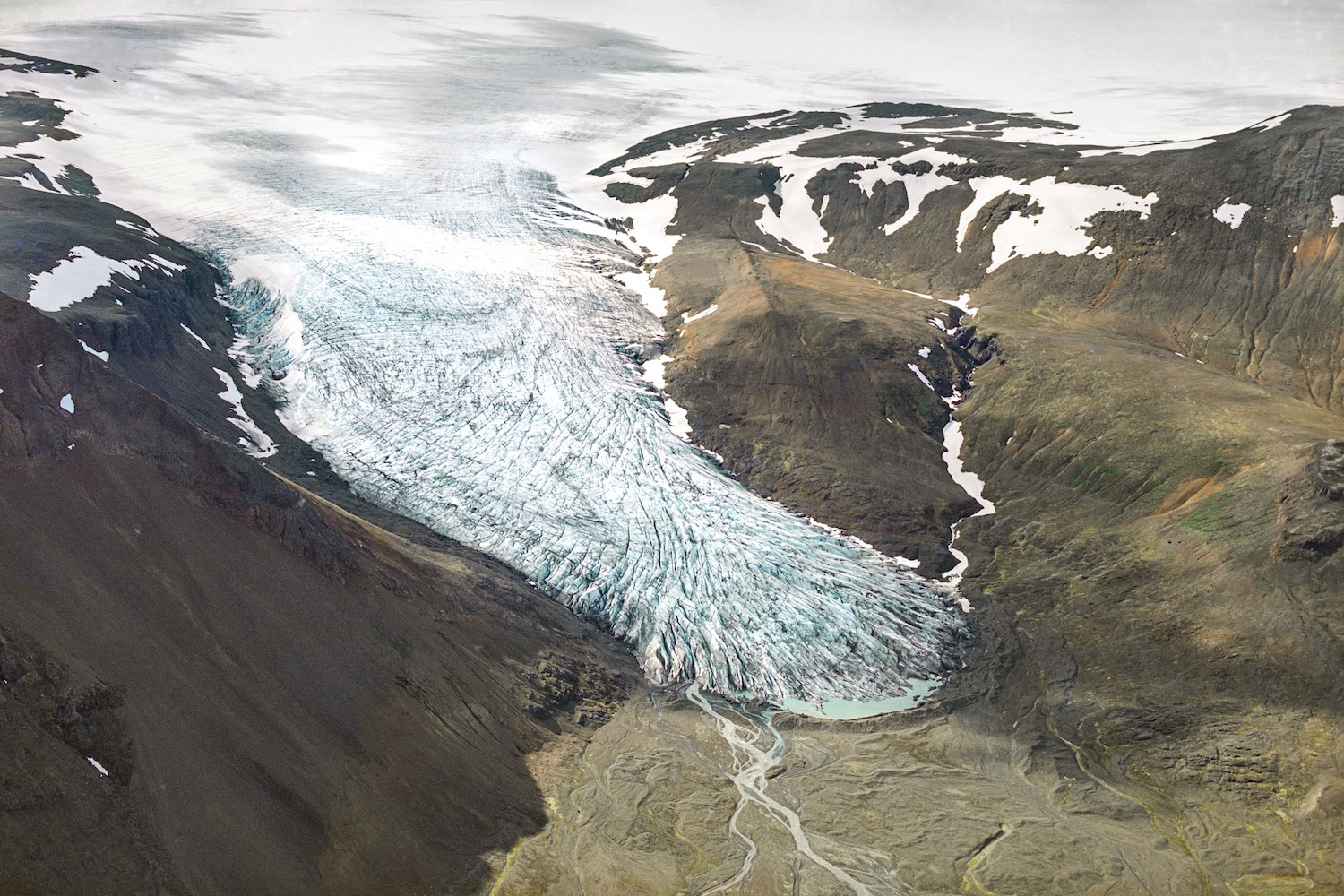

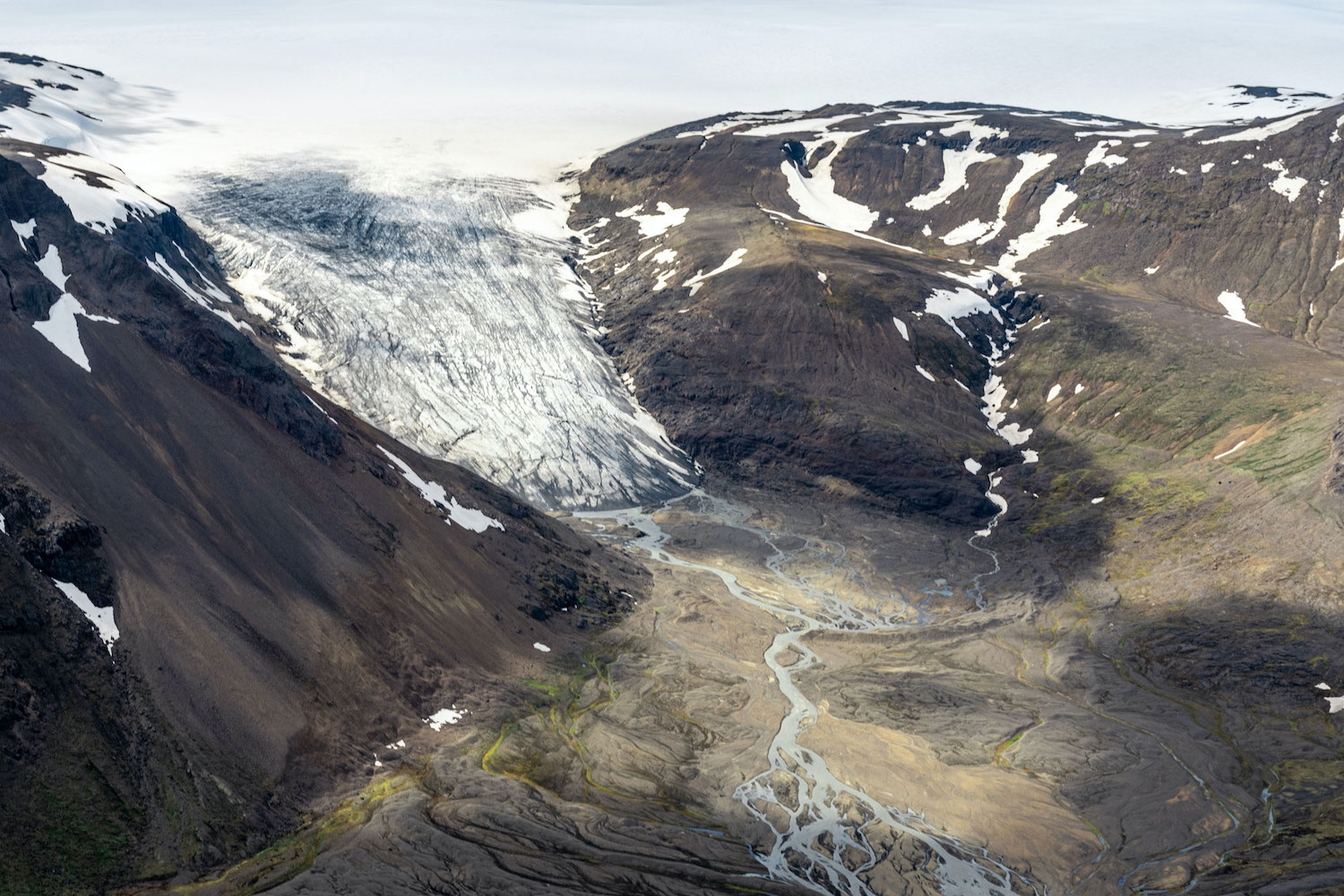

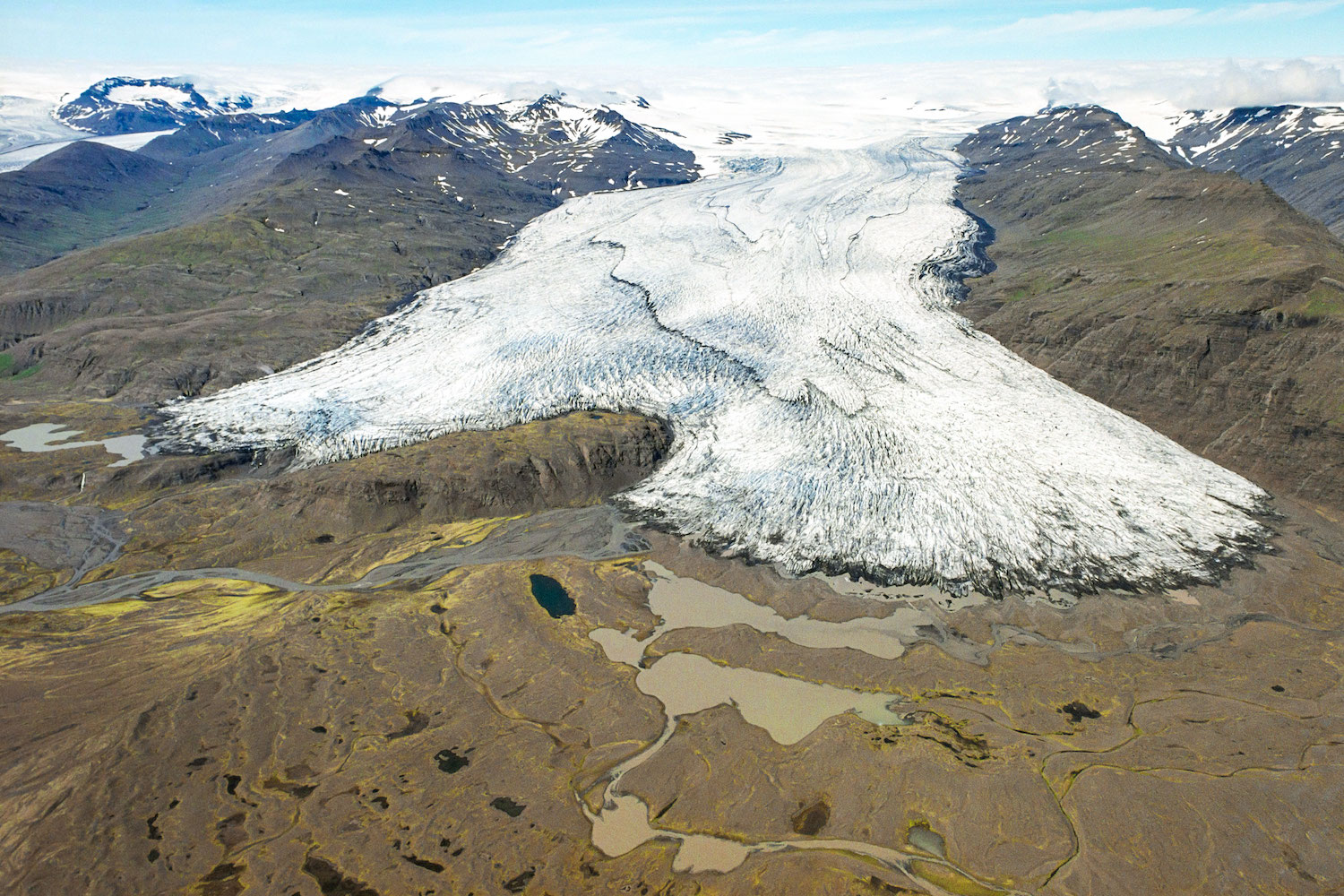

A series of thirty photographic prints are hung in an evenly spaced grid on a white wall in London. The same series of thirty photographic prints are hung in a horizontal line across three white walls in Reykjavík. Each print is composed of two images, side-by-side. The images on the left are of a jökull (Icelandic for glacier), its likeness captured from a small plane in 1999. The image on the right is of the same glacier, its portrait taken in 2019, twenty years later. This 1999/2019 work, “The glacier melt series,” by Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson, which was exhibited at both Tate Modern and Reykjavík Art Museum, Hafnarhús, introduces us to the disappearing charismatic landscapes1 of the cryosphere, the melting glaciers of Iceland.

There is much that has been measured and written — and there remains much to be measured and written — on landscapes of the climate crisis. The seemingly endless stream of numbers that are supposed to communicate urgency to us, like degrees warmer, meters rising, species disappearing, are here replaced by what appears to be an absence but is, in fact, the atmosphere as it meets the ground. Here, distances between then and now are brought into relation through the act of cataloging bodies of ice — in this case, glacial tongues, once lapping out, languidly, into landscapes they were intimately familiar with, have disappeared, changing form, melting into glacial rivers, meeting the same landscapes but differently, now as freshwater making its way to the ocean, where it will accumulate, change the temperature, the salinity, the currents, and, ultimately, our climate. How does the land and the ocean meet? Like this, thirty times over. Like this, more times over than we can comprehend. But, if, as Roni Horn says, “Iceland is a verb,” then “its action is to center.” 2

Despite knowing better, the glaciers of our geographic and cultural imaginations have become monolithic bodies. They are depicted — either from above through satellite imagery or below, photographed or filmed as glacial tongues moving back toward the sea — as slow-moving masses of ice and snow, moving imperceptibly through space and time. But recent artistic endeavors — such as Eliasson’s long-term photographic series, the film-based research of Susan Schuppli’s Learning from Ice, and the permanent installation of Vatnasafn (a library of glacial water) initiated by Roni Horn — tell us stories of glaciers as communities of individual bodied entities. They tell us of their formation, their movement, and their inevitable melt. These, too, are stories of friction and pressure, of bodies upon — and within — bodies, of worlds upon — and within — worlds.

Reflecting on his experience photographing Iceland’s glaciers, Eliasson asks, “How do we translate what we know into what we do? […] What is the distance between thinking and doing?”3 I would like to take up these questions, for what are our contemporary crises if not explicitly about bodies acting with and against bodies? The crisis of the pandemic has reminded us that our life on earth, at all moments, is prone to risk; our very bodies are always already “hosts for elements that are alien to us at every level of existence.”4 The urgent anti-racism protests — often coupled with calls to defund North American police forces — reverberate, resoundingly, calling for the end of systemic violence against Black bodies and calling out for all to hear, without equivocation, that Black lives matter. These bodied perspectives offer what is most radical and urgent, necessary to understanding our engagement and response to the climate crisis. How, then, do we begin to respond to the questions laid bare by these concurrent crises?

As Heather Davis compels us, we must situate ourselves in relation to other bodies, for, “Every time we breathe, we pull the world into our bodies: water vapor and oxygen and carbon and particulate matter and aerosols. We become the outside through our breath, our food, and our porous skin. We are composed of what surrounds us. We have come into existence with and because of so many others, from carbon to microbes to dogs. And all these creatures and rocks and air molecules and water all exist together, with each other, for each other. To be a human means to be the land and water and air of our surroundings. We are the outside. We are our environment. We are losing, with the increase in aromatic hydrocarbons and methane and carbon, the animals and plants and air and water that compose us. In this time of loss, we need to imagine.”5 By recognizing the multitudes of ways our mutual vulnerabilities are the result of our co-constitution with other bodies, we can begin to understand how bodies are always a part of a planetary metabolism. In such a “processual picture of the planet,”6 we can see how we are radically open, with only limited abilities to protect ourselves and others, for we are all inherently constituted with and toward other bodies — viruses, humans, oceans, atmospheres.

Scenes in a documentary film linger in the freezers of the Canadian Ice Core Archive at the University of Alberta and the laboratory of the Ice Core and Quaternary Geochemistry Lab at Oregon State University, focusing on the “different knowledge practices from cryospheric science to indigenous traditions that engage with the material conditions of ice.”7 In Susan Schuppli’s 2019 film, Learning from Ice, glaciers come together as communities of individual entities, living and nonliving, under the pressures of temperature and atmosphere. Glaciers begin to form when snow falls, remains, and accumulates in the same area throughout the year, year after year. As layers of fresh snow fall onto older snow, any and all particles — soil, pollen, particulate — become trapped between old snow and new snow, and as the weight of the new snow presses down, forcing air out from between the flakes of snow (in what becomes called the snowpack), material traces of the time between snowfall and compression become trapped between molecules and within small air bubbles. As more snow accumulates and as the snowpack and ice move down to depths of hundreds of meters, the air bubbles become subsumed into the crystalline structure of the ice itself; though glacial ice can appear to have no air bubbles, it still holds trapped air. As the snow turns into ice, and as the ice begins to flow outward and downward under the pressure of its own weight, it becomes a glacier. Schuppli’s artistic research expressly reconfigures and recasts glaciers (her work focuses on Arctic environments) as a “vast information network composed of material as well as cultural sensors that are registering and transmitting the signals of pollution and climate change.”8

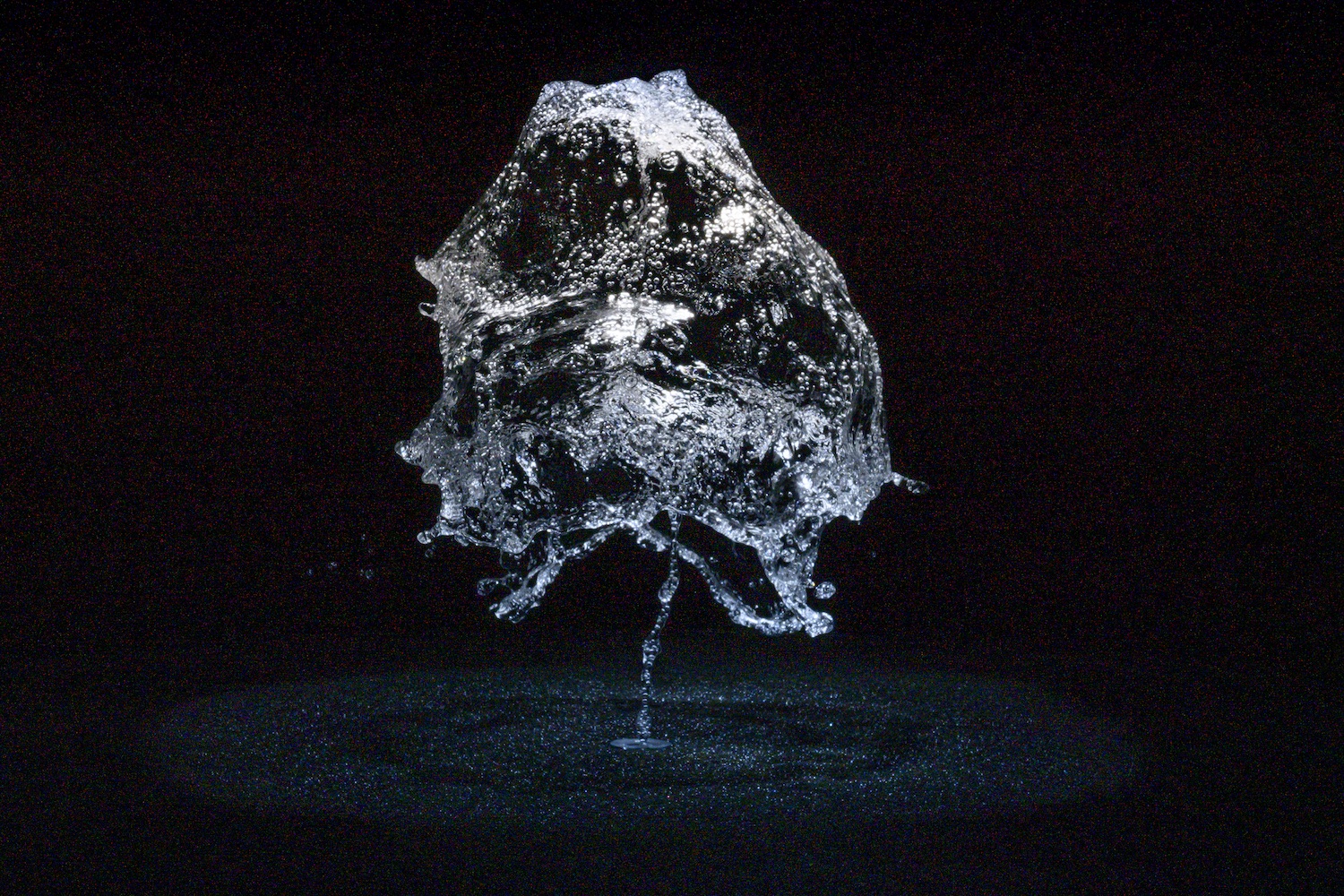

It is under the pressure of its own bodied weight — gravity, the force of the atmosphere — that a glacier begins to move, flowing out and down valleys (valley glaciers) or out in all directions (continental ice sheets), internal deformations pushing, sliding, over rocks and sediment at the glacial base; the body of the atmosphere pushes down upon the body of the glacier that pushes down upon the body of the earth. Increasing temperatures, evaporation, microbes, and other particles deposited and otherwise flourishing on the surface of glaciers, alone and together, trigger and amplify glacial ablation, melt, and, ultimately, retreat.

Iceland has 268 named glaciers — it famously had 269 until 2014, when Oddur Sigurðsson, a glaciologist at the Icelandic Meteorological Office, declared Okjökull dead, a glacier no longer thick enough to move. Materially, Ok continues to exist in two places: as a still-shrinking area of ice and snow on the surface of Iceland; and as glacial meltwater, in one of twenty-four floor-to-ceiling tubes filled with the liquid of twenty-four of Iceland’s glaciers, each of which is melting and receding as I type this and, later still, as you read this. These tubes are housed in Vatnasafn on a promontory in Stykkishólmur, a library of water that is on its way to becoming an archive of lost ice, of lost landscapes, and, by extension, lost futures. It was proposed and installed by Roni Horn, who imagined Vatnasafn as “the most beautifully situated library in the world” and “a lighthouse in which the viewer becomes the light.”9 And of the library’s beautiful situation? Described by Horn as “serendipitous coincidence,”10 the library stands on the very same spot where the first monitoring of meteorological conditions in Iceland was undertaken in 1845.

Much like meteorological monitoring — the sensing and collection of atmospheric data in the service of understanding and forecasting weather — these artworks are also about sensing, collecting, and visualizing glacial phenomena to understand and elucidate glaciers as more than charismatic landscapes: they are bodies composed of bodies in a complex, interrelated system of planetary metabolism. So, too, are these artworks bodies, existing in relation to each other, and only when Olafur Eliasson’s work — specifically his glacial melt series but also his larger body of research and documentary-based studio work — is situated in relation to Horn’s Vatnasafn, to Schuppli’s Learning from Ice, can it perform the work that science cannot yet do. Together they can communicate the complexity of bodied planetary experience, its consequences, and the increasing urgency of phenomena that used to be outside human timescales but can now be captured — and responded to — in scales of decades, in scales of years, in the scale of now.

*I am indebted to Marco Ferrari and Jingru (Cyan) Cheng, whom I have the pleasure to teach ADS7, Something in the Air: Politics of the Atmosphere at the Royal College of Art School of Architecture in London, and who have been generous interlocutors on all things atmospheric and glacial. A special thank you to the students of ADS7 and, in particular, Nico Alexandroff, a Master of Architecture student whose work on Greenland’s southwest coast has been an extended opportunity for us to linger on questions of indexical ice. Thanks also to Andri Snær Magnason, Heather Davis, Jussi Parikka, Lukáš Likavčan, and Susan Schuppli, for meeting with us in Reykjavík, London, and online, and for taking such care in sharing their stories and their work.